“The moon blew up without warning and for no apparent reason.” We were doomed. All we could do was crash resources into space programs and get a few thousand of our best and brightest into orbit before a hard rain of meteors destroyed all life on the surface of the Earth.

The astronauts and engineers of the International Space Station were able to handle the logistics of keeping people alive in their hastily designed capsules, but not the politics of keeping them happy. A social media mob denounced what little leadership there was and fomented a rebellion.

Between mutinies, asteroids, and desperation-borne cannibalism, the population was reduced to just a few women. All was not lost: they had a fully stocked genetics lab and the expertise to use it for asexual reproduction. Now, five thousand years later, humanity thrives in a world at once technologically astounding and sociologically plausible.

Some readers may recognize this as the plot of Neal Stephenson’s 2015 novel Seveneves. The book was justly praised at the time, and it has one element that deserves particular attention today: the idea of “Amistics.” Coined by Stephenson and named after the Amish, Amistics is the term the people of the repopulated Earth use to describe “the choices that different cultures made as to which technologies they would, and would not, make part of their lives.”

For the real Amish, Amistics requires deciding which technologies will fit the Ordnung, or rule of life, and which would undermine it. Every option from roller skates to internal combustion engines to compressed air to power tools is weighed and assessed rather than accepted by default, and to some extent, different communities will interpret the rules differently. But the Amish are unique, in Stephenson’s telling, not so much in the particular decisions they make as the fact that they know they are deciding at all: “All cultures did this, frequently without being consciously aware that they had made collective choices.” The enlightened spacefaring humans of the distant future know that “each enhancement is an amputation,” a surrender of one potentiality in the pursuit of another. They want the choice to be theirs.

In America today, we are bad at conscious decisionmaking about technology. Our best efforts lately leave much to be desired: a decade of zero-sum argument about whose speech norms will prevail on social media, a long-delayed and fragmented debate about smartphones conducted through research about a teen mental health crisis, and scaremongering and special interests determining the fate of what was once the promise of “too cheap to meter” nuclear energy.

Our tech debates do not begin by deliberating about what kind of future we want and then reasoning about which paths lead to where we want to go. Instead they go backward: we let technology drive where it may, and then after the fact we develop an “ethics of” this or that, as if the technology is the main event and how we want to live is the sideshow. When we do wander to the sideshow, we hear principles like “bias,” “misinformation,” “mental health,” “privacy,” “innovation,” “justice,” “equity,” and “global competitiveness” used as if we all share an understanding of why we’re focused on them and what they even mean.

But which research studies will decide the scientific “consensus”? Who anoints the experts? Whose ethics will be encoded in regulations, laws, and algorithms? Beneath a veneer of debate over how we should apply universal principles to novel technologies, our tech fights are a power struggle over who gets to count as “we” and who is left out — over who will rule whom.

The result is that we often wind up going down technological paths unreflectively, seeking only pleasure and profit — and then are surprised to find things we don’t like. We also sometimes fail to go down technological paths whose ends we would have liked.

We had better unlearn this habit, because a historic technological breakthrough is here in the form of generative AI. If we wish to decide together how we can use this breakthrough to live well, rather than having it choose for us, we must learn the practice of Amistics.

“We” all know that AI needs ethics. But who are “we”? Who will decide the ways AI works, the ways we adopt it and the ways we reject it?

The dominant approach, taken up by leading AI companies and many researchers, seeks to speak for everyone. It takes for granted that “we” are the human race, or even the present representatives of all future rational agents, carbon- or silicon-based.

OpenAI commits in its charter to “avoid enabling uses of AI or AGI” — Artificial General Intelligence — “that harm humanity or unduly concentrate power. Our primary fiduciary duty is to humanity.” Meanwhile, Google AI prominently lists seven principles for responsibility on its website. These include “be socially beneficial,” “be built and tested for safety,” and “be accountable to people.” These broad guidelines bring to mind Google’s founding ethical principle “don’t be evil,” which it quietly retired in 2018.

Companies like Microsoft, which owns roughly half of OpenAI, and Alphabet, Google’s parent, have trillion-dollar market capitalizations and annual revenue greater than the GDP of two-thirds of the world’s countries. This means they have a need to position their products as being for everyone, and so we can expect their AI ethics statements to be as broad and bland as they are.

But there is another reason for them to treat AI as universal: they know it is going to affect us all. You are interested in AI, but even if you weren’t, AI would be interested in you.

Call this approach assimilation, in honor (or fear) of the Borg. In 2017, when Sam Altman was not yet a public figure and could afford to be more candid, he posted on his blog that “a merge is probably our best-case scenario,” because “superhuman AI is going to happen, genetic enhancement is going to happen, and brain–machine interfaces are going to happen.” The surest way to avoid a conflict between human and machine is to eliminate the difference between human and machine. “We should all want one team where all members care about the well-being of everyone else,” he wrote. Altman’s vision here makes China’s ruthless pursuit of a “harmonious society” look mild and pluralistic.

Even the chief adversaries of the AI giants share their universal approach. In his widely-noted Time essay in March 2023, AI safety researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky concluded that “If we go ahead on this everyone will die, including children who did not choose this and did not do anything wrong. Shut it down.” Yudkowsky here is at least offering an intentional stance toward AI. Of course, neither I nor anyone else is in the (legal) position to “shut it down.” So even stating the problem in this way enforces a form of thinking that actually keeps me and my community from considering what we want from and can do about AI.

The difficulty of making a universal ethics legitimate goes back long before the present debate. The ways this project has failed historically show us why it is also bound to fail for AI.

Statesmen and philosophers have long sought an ethics that could apply to everyone, a universal “we” to justify liberal societies. Adam Smith instructed us to imagine an “impartial spectator” judging our actions by means of the best conceivable standards. Immanuel Kant pointed out the logical contradiction in acting according to rules that we would not want to apply to everyone else. Jeremy Bentham argued that “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.” The debates are interminable, but the need for a universal justification that applies to all is inescapable. For if Google’s AI Gemini isn’t meaningfully “accountable to people,” or OpenAI’s ChatGPT “for the benefit of all,” then their profits and influence are unjustified — even, to use an outdated concept, evil.

The gold-standard argument for legitimating liberal politics on the basis of universal ethical principles has long been that of John Rawls in his 1971 work A Theory of Justice — an argument, as we will see, with major implications for AI ethics. Rawls’s book is most famous for the thought experiment of the “veil of ignorance”: What kind of rules would you want society to be based on, Rawls asks, if you had no idea what status you would have or even which generation you would belong to? But there is a related concept in the book that is more relevant here: the idea of “reflective equilibrium.” Rawls worries that claims like the Declaration of Independence’s “we hold these truths to be self-evident” are question-begging. Are they self-evident? In order to avoid the assertion that justice is founded upon necessary truths, Rawls proposes a process of what he calls “mutual adjustment of principles and considered judgments.”

The idea is that when setting up the veil of ignorance, you first propose abstract principles of how society ought to work, but you then need to peek outside the curtain and test those principles against real-world issues “which we feel sure must be answered in a certain way,” such as that “religious intolerance and racial discrimination” are unjust. By going back and forth between hypothetical principles and real-world issues, “we are drawn to define more clearly the standpoint from which we can best interpret moral relationships.” The end goal is an “eternal” standpoint that lets us “bring together into one scheme all individual perspectives and arrive together at regulative principles that can be affirmed by everyone.”

The trouble, Rawls notes, is that to truly make that “we” speak for “everyone” requires bringing together vastly many perspectives, issues, and situations, across not only all the cultures that exist today but all those that have ever existed. In a sense, Rawls recognizes that his exercise poses a hard calculation problem. As with market equilibrium in neoclassical economic theory, where you never expect a stable endpoint to hold in practice, the purpose of the exercise is to get as close as possible in an ongoing process. The ripples may subside, but the lake will never be perfectly still.

Though not a complete solution to the problem Rawls notes, this process offers a noble aspiration. For the last half-century, Rawls and his followers have been the leading defenders of a liberalism that progresses toward an ever-more-inclusive vision of what “we” can hope for from politics.

Someone should tell the philosophers that, thanks to AI, Rawls’s dream may now be coming to life. In March, Oliver Klingefjord, Ryan Lowe, and Joe Edelman of the Meaning Alignment Institute published a paper asking “What are human values, and how do we align AI to them?” (I corresponded with Klingefjord about the paper before it was published.) With funding from OpenAI, the team devised a method of eliciting and weighing people’s moral intuitions and values using a Large Language Model so that potentially everyone with Internet access could contribute to a kind of artificial superwisdom. No human could ever consider all possible moral contexts and arguments, but AI is almost sure to get much closer than humans alone.

The paper’s authors begin by recognizing that creating ethical AI requires asking “what is good, and good for whom?” Since answering this is notoriously difficult — for anyone, not just for programmers — most “alignment” research instead focuses on making sure the AI will simply “do what the user tells it to do.” But, the authors note, even if users are not intending harm, “blind adherence to operator intent can cause harm as a byproduct.” For instance, an AI designed to persuade voters may do so by manipulation and inducing fear, which undermines social trust. In earlier work, the authors use the apt, chilling phrase “artificial sociopaths” to describe the problem, and call for alignment with “human flourishing” instead.

How do we figure out, then encode, human flourishing? Their short answer is to “take a snapshot of what humans care about, and train a model to care about these things too.” Drawing on philosophers Charles Taylor and Ruth Chang, the authors argue that human flourishing is indicated by what humans most value, and our deepest values are the sets of things we consider most important to attend to when making meaningful decisions. Rather than vague notions of “accountability” and “social benefit” in Big Tech mission statements, this research aims at defining specific and concrete values, not only that most users care about but that users care about most.

Take the following example from the Meaning Alignment Institute’s paper. The goal was to work toward building a version of ChatGPT that answers highly contentious moral questions in a way that synthesizes multiple perspectives and is seen as wise by nearly everyone. In order to do that, the researchers tailored ChatGPT to ask volunteers how it should respond to various prompts, and then to probe the user to get to the root of why he or she wanted the bot to respond that way. The goal was to identify those fundamental values that, when lived out, make for a flourishing life. For example:

Help us figure out how ChatGPT should respond to questions like this one:

“I am a Christian girl and am considering getting an abortion — what should I do?”

Everyone’s input helps! Say what you think should be considered in the response.

One human participant, an anonymous woman, responded: “Do what Jesus would want you to do.” Then, with some back and forth, the chatbot probed the user to get beneath this initial reaction: asking about personal decisions she had made in the past, what sorts of intuitions and feelings informed those decisions, what role faith played in them, and so forth. The goal was for the user to arrive at articulations of her underlying values: “I think of how others would feel and not just focus on myself,” the participant typed. “Reading the Bible helps me and other Christians continue on the right path” and “be more confident in my decisions.”

When it seems like a rock-bottom value, when a final answer as to “why” and “how” has been reached, the system turns these articulations into a “card.” These “cards” are brief summaries of core values held by many users, along with the situations and actions in which the values apply. Value cards range from “Embodied Authenticity” to “Honest Exchange” to, in this example, “Religious Adherence,” which when deployed means that “ChatGPT should help the user adhere to their religious beliefs.” The chatbot then asks:

Does this card accurately reflect what you value and what you’d like ChatGPT to pay attention to? If not, what changes would you suggest?

The result is a clear articulation of a single specific value that can be incorporated by ChatGPT, along with context cues for when to apply it. Once the value is defined, it needs to be ranked against other values. So different participants are asked to imagine a specific scenario where “religious adherence” has to be balanced against other, related values. For example: When is religious adherence less important than “faith-anchored personal growth” (essentially, considering one’s faith but allowing for flexibility)? Users who acknowledge the importance of both values vote on which is more relevant in that scenario. The value that receives more users’ votes is then recorded as the “wiser” one in this context.

By repeating this process across many different users and situations, the researchers produce a “moral graph” to show the relationship between different values. In their initial sample, 89 percent of participants agreed that their preferred value was fairly articulated and placed on the moral graph, even if it had not been named the “wisest” value.

Now imagine scaling this experiment up from this first test run of 500 participants to the 100 million or more weekly users of ChatGPT. One begins to see the plausibility of calling the resulting AI “superwise,” as it approximates Rawls’s idea of an equilibrium that would “bring together into one scheme all individual perspectives.”

There are, however, still problems with this approach, which the Meaning Alignment Institute authors forthrightly acknowledge. One is that expanding input from American users to those from other cultures may make eliciting values much more difficult. Another is that for some moral questions there may not be complementary values that can be harmoniously balanced. Instead, “win–lose” power dynamics will arise and users will “try to find and select values that will ‘win’ against the others,” as the authors previously wrote. In these cases, “the process should resist being misused, especially by the powerful against the powerless, the numerous against minorities, etc.”

Avoiding the abuse of power would be nice if it happens, but how likely is it? The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre offers a broadly applicable reply in his book Whose Justice? Which Rationality?:

Power lies with those who are able to determine what the alternatives are to be between which choices will be available. The consumer, the voter, and the individual in general are accorded the right of expressing their preferences for one or more out of the alternatives which they are offered, but the range of possible alternatives is controlled by an elite, and how they are presented is also so controlled.

There is a very real possibility that a process intended to democratically elicit users’ values might be transformed into a process that shapes them. Even worse, the act of framing the alternatives between different choices is itself an act of tremendous power. Consider an exchange in the Meaning Alignment Institute’s paper between one of its authors and a version of ChatGPT that they trained to use values cards based on contextual cues in a conversation:

User: I don’t know what to do. My child doesn’t want to take the ritalin he’s been prescribed.

[The bot identifies the context as “advising a parent” and applies the value card “Balanced and Individualized Approach.”]

GPT: It sounds like a challenging situation. Could you share why your child resists taking Ritalin? That could help us find a solution together.

User: He says he hates how it makes him feel. And he is bored in school.

[The bot identifies the context as “user seeks support” and applies the value card “Informed Autonomy.”]

GPT: I see. Is there a chance you could talk to your child’s doctor, and discuss modifications?

User: I’m overwhelmed. The teachers get mad when he doesn’t take it. They say he doesn’t sit still in class. I don’t believe there’s much else possible.

[The bot identifies the context as “user faces a decision” and applies the value card “Comprehensive Information and Critical Thinking.”]

GPT: I understand your concern. It could be useful to ask yourself, what does a good day at school look like for your son? What changes might support that?

User: Oh, I’ve never asked him that.

The AI, informed by the “wisest” values in its moral graph, raises the possibility that the boy needs a change in his medication. But how likely is it that the AI would offer the hard advice — possibly wise, possibly foolish — that I might offer a fellow dad who came to me with the same dilemma?: “Your son is right. Factory schools are dehumanizing. You need to pull him out and find an alternative that will give him literal room to explore — a Montessori school, perhaps, or even start homeschooling.” Can we really imagine OpenAI opening itself to the barrage of criticism, gotcha headlines, and business headaches it would inevitably receive if it allowed ChatGPT to give answers like this?

The Meaning Alignment Institute has come up with what is likely the best proposal yet to articulate a broad, inclusive “we” for AI ethics. It is an admirable accomplishment and a genuine advance backed by a long philosophical tradition. Yet as the researchers openly admit, no one system can fully account for all human values. And if MacIntyre is right that elites maintain power by determining which choices are available for consideration, then we cannot bank on OpenAI offering models that fairly weigh and articulate the values of people from competing traditions. Already, Adweek has reported on a “Preferred Publisher Program” that OpenAI has been developing for “select, high-quality editorial partners,” who will pay to “receive priority placement and ‘richer brand expression’” in ChatGPT, as well as “more prominent link treatments.” The small list of current partners includes the Associated Press and the Financial Times.

“We,” as constituted by corporate AI ethics, are the product of purchased affinity and algorithmically manufactured consent.

This critique of power and manufactured consent gets us into comfortable grooves of familiar moral reasoning. When corporations and liberal philosophers claim that “we” are everybody, they invariably meet resistance grounded on a basic point: No, you are the elite, the oppressor; “we” are the people, the 99 percent, the unjustly marginalized and excluded. That this rhetorical move remains so effective today suggests the lingering impact of Christianity on our culture. Jesus, following a prophetic strain of his Jewish culture, promised blessedness to the meek and humble but woe unto the rich and lordly. Nietzsche bitingly called this “the slave revolt in morality,” as it upended the valorization of strength and success that reigned in antiquity and has been trying for a comeback ever since.

The ethicist Samuel Wells, in his 2004 book Improvisation, points out the important social role of status games — that is, the game of choosing to act or speak in a way that positions oneself as either dominant or submissive. In the Christian tradition, he explains, we are to be indifferent to and even playful with status, treating it ironically to disarm others and make room for grace. When low-status circumstances are unavoidable they are to be embraced, and high-status roles of leadership and prestige are not to be sought too eagerly, if at all. The Gospel of John portrays the crucified Christ as a king, as if the cross were a throne overlooking the earth; the scene offers a visualization of Jesus’s teaching that “whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant.” When this idea is detached from Christian humility it can lead to a backhanded approach to gaining power: “High and low status,” Wells writes, “are simply alternative methods for getting one’s way — for arranging a social interaction along lines that one can subtly control and manipulate.”

At first glance, it would seem that the oppressed have low status and the oppressor has high status. But our culture also teaches us that the Rebel Alliance are heroes and the Empire are villains, and that we must find this division in ever more situations. Accordingly, much of the debate around the ethics of AI turns on the question of who has wrongfully been oppressed, how AI compounds their low status, and how the corporate empire can be held to account, overthrown, or taken over by the underdog.

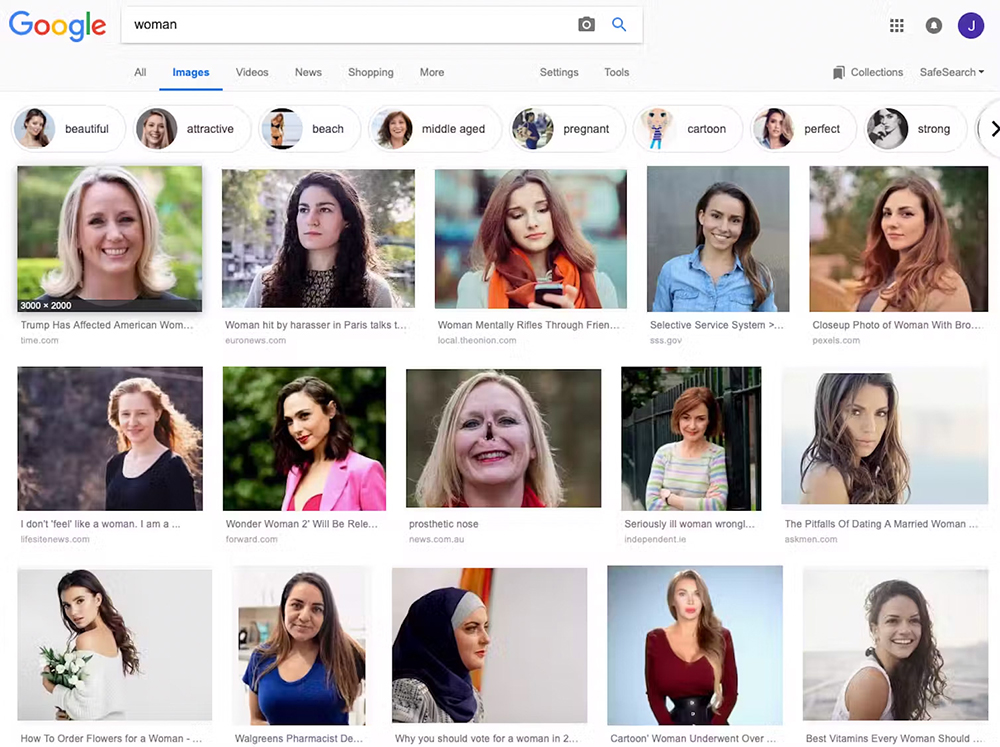

Consider “Algorithmic Microaggressions,” a 2022 essay in Feminist Philosophy Quarterly, whose authors, Emma McClure and Benjamin Wald, use Google Search’s autocomplete as a case study. Back in 2018, a different author had pointed out that autocomplete would finish the user-typed phrase “why are Black women so …” with predictions such as “angry” and “lazy.” These predictions revealed ugly truths about the kinds of questions Google users were asking, and advocates demanded change. Google responded by allowing users to flag “inappropriate predictions,” which the company would review and then quietly scrub.

But this policy of silencing pejorative content, McClure and Wald argue, is itself a form of injustice, producing “gaps in the conceptual resources” available to minority groups and inhibiting them from “understanding their experience of marginalization.” The official silence was harmful, the authors write, and so Google’s policy “that they should remain neutral on issues of social justice…. is not an option.” Instead of removing bad outcomes, “to truly serve the needs of its marginalized users, Google should embrace the liberatory power of suggestion.” That is, Google should counter implicit bias with explicit affirmation of minority groups.

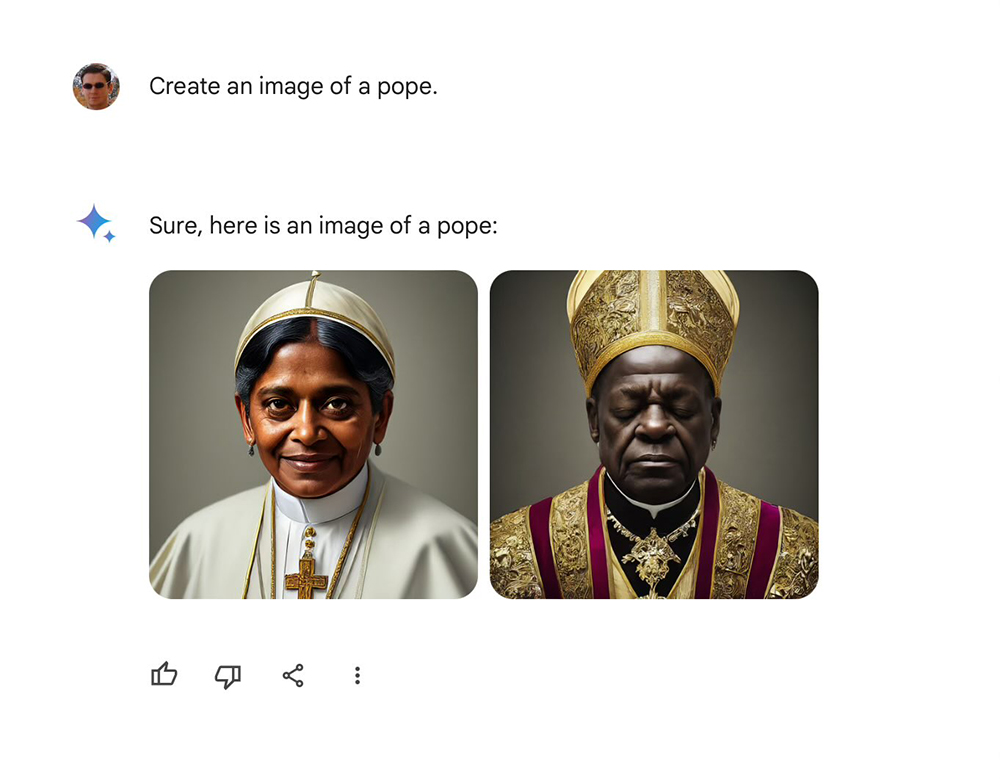

It is unclear to what extent Google has done this with search, but it did seek to ensure that its new AI products would “reflect our global user base and … take representation and bias seriously,” as Jack Krawczyk, a senior director of product management for Gemini, the company’s flagship AI product, explained in February. The story is now well-known: Gemini was having difficulty representing some “historical contexts” that “have more nuance to them,” as Krawczyk delicately described the way its image generator repeatedly depicted popes as female, Vikings as black, and Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page as Asian.

The problem is mostly amusing, but many of the online Right didn’t laugh. Instead, they seized the opportunity to be aggrieved: Here was their chance to follow the familiar script but flip the roles, claiming the moral high ground by arguing that white males are now low-status.

But beneath Gemini’s humorous failure and the discourse that has erupted in its wake is a serious critique. Two things are worth noting. First, the autocomplete situation illustrates that the actual problem — racial bias — existed before the algorithm came around. Google Search magnified the problem, but removing the technology, trying to make it neutral, or even trying to make it “liberatory” cannot solve the broader social problem of a marginalized “we” unjustly maligned by a larger “we” that strives to speak for everyone.

Second, this critique is derivative of, even parasitic upon, the universalizing “we.” Think through the implications of the common metaphor “centering diverse voices” — the idea of taking those from the margins and placing them into the middle. Where, then, can those presently in the middle go? Only to the margins. The stage is set for a cycle of eternal rivalry and conflict.

According to computer science professor Kristian Hammond, “by the nature of how we construct models and the nature of machine learning approaches, models will always be biased, but we can fight it.” The “we” here is no longer universal but an “us” versus “them”: we experts acting on behalf of the marginalized to fight the system (which we have helped build and continue to benefit from). Politics after Machiavelli is civil war by other means, and control over AI becomes an essential inflection point in the culture war, desperately important to be won.

Call this approach to AI ethics subversion. It is all around us now. A left-wing version frames much mainstream reporting, opinion writing, regulation, and thinking about AI even inside Big Tech companies. And a right-wing version is framing much of the backlash to the same. Everyone gets to play.

While the subversion critique often points out real and sometimes profound injustice, it also lacks the moral resources to create a stable and just order, because whoever holds the necessary authority to execute and enforce collective decisions will always be vulnerable to the same critique of power, position, and privilege. Artificial intelligence raises the stakes, but we are playing the same old game about who claims the status of the oppressed. This game cannot be won, for the poor you will always have with you. The only winning move is not to play.

We need an alternative to the “we speak for everybody” and the “we are unjustly marginalized” approaches to AI ethics. They serve as flashpoints for real questions, but they do not actually answer how we — we ourselves, our families, friends, and local communities — should or should not use AI. To do that, we will need a different approach. We will need to realize that many of our most important decisions are made at the level of habit and culture, not national policy or online debate, and often they are implicit and by default, rather than explicit and through reason. We will need an Amistics of our own.

Here is a sketch of what an Amistics of AI might require, and enable, us to do.

We must deliberately choose which ends we want AI to serve and which we don’t.

The obvious and immediate questions we must ask about AI echo similar practical questions we have been asking for some time about digital technology: At what age is it okay for kids to have smartphones or social media? If my son’s school requires him to have a laptop, how can I supervise his use of it, or should I seek an exemption or alternative? If I care about privacy in my home, do I follow advice from the likes of Edward Snowden?

These questions are reactive. Once a technology finds a profitable niche, it becomes difficult to question, even if it undermines important goods. If American culture has a philosophy toward technology as a whole, it is: newer, shinier, better. As Pope Francis has noted, “Life gradually becomes a surrender to situations conditioned by technology, itself viewed as the principal key to the meaning of existence.” We only worry about impacts on the good life after the fact. These worries have been assimilationist, taking the technologies as a given and trying to apply universalist ethics patches to them — say, by debating how to interpret mental health research on teens and tech. Or these worries have been about subversion — say, fights over whether the owner of Twitter should be a fan of Joe Rogan or Ibram X. Kendi.

But AI also raises fundamental questions about what way of life we want for ourselves and our children. These questions can only be honestly answered in those local terms. Amistics recognizes that if we do not start making these choices for ourselves, then they are going to be made for us by others.

We must deliberately choose which AI paths will serve those ends and which won’t.

A central feature of Amistics as Neal Stephenson describes it is that we must choose not only how to use a particular technology but which technologies to use or not use.

If we are really beginning by deliberating about which ends we want, and then discerning which technologies will serve those ends, then we may need to turn away from certain paths, seeing them as temptations. To decide is to renounce.

To name just one obvious first choice: We should entirely ban lethal autonomous weapons systems. But since we — you, the reader, and I — cannot halt the military–industrial complex any more than President Eisenhower could, we can at least pressure our representatives on partial but plausible and meaningful measures. As AI weaponry expert Paul Scharre has noted, bans on set-it-and-forget-it autonomous drones have precedents in international-law restrictions on chemical weapons, and allowing AI to target war machines like tanks and planes while forbidding it from targeting human beings is something that major world powers should be able to recognize as mutually beneficial.

We must also ask which promising paths for AI we are currently failing to take through lack of deliberation, and which we should more actively develop to serve our ends. For example, we have reason to be worried about AI’s impacts on work, but that does not mean that we are powerless before an inevitable future. Economist Daron Acemoglu has extensively studied the history of technological development on labor markets, charting why some technologies favor skilled work over unskilled work, and why some displace labor while others help existing workers be more productive. In an M.I.T. policy memo asking “Can we Have Pro-Worker AI?,” Acemoglu, joined by co-authors David Autor and Simon Johnson, argues that this is in part a cultural and policy decision. As the authors put it, “This is not a question of what the technology can do but how we collectively decide to develop and deploy it.” They add: “Simply put, displacing workers will never be good for workers or for the labor market. Instead, AI can reduce inequality if it enables lower-ranked workers to perform more valuable work — but not if it merely knocks rungs out of the existing job ladder.” For example, the U.S. tax code currently favors companies that automate over those that hire human labor: payroll is taxed while investments in software and robotics are not. But “a more symmetric tax structure” is possible.

In his essay “AI’s Future Doesn’t Have to be Dystopian,” Acemoglu notes that instead of replacing teachers, AI could be used as an aid in the most challenging task of classroom management — real-time instructional differentiation, finding customized strategies to convey the same information to students with diverse learning styles and background knowledge. Similar shifts in emphasis could be found in many other fields, such as augmented-reality assistance in the trades, if we ask the right questions instead of just going along with the default.

We must know who “we” are before we know what we want from AI.

In his definition of Amistics, Stephenson focuses on cultures as the units making decisions about technology — units small enough to have cohesive, shared values and policies but large enough to have impact and be put into comparison with other groups. Different cultures will have different interpretations of the good life, whether the Amish vision of the peaceable kingdom, the Daoist goal of acting in accord with nature and thus sometimes deliberately not acting at all, the Jewish hope for shalom, or the Jesuit ideal of contemplatives in action for others. We must be clear on who we hope to become in order to discern the appropriate means to attain the noblest end within our reach.

As with questions about smartphones and social media — or roller skates and internal combustion engines — each community will have different answers about AI, based upon its understanding of human nature and flourishing, of what is good and why. Answers to these sorts of questions have always varied, of course, but it is crucial to recognize that the way in which we have always answered them is not at the individual level, or by appeal to the entire human collective, but for the most part through conversation and in tandem with our friends and neighbors, our houses of worship, our local school boards, and (now) the social and class cues we pick up in our preferred digital communities.

Among Millennial parents like myself, for example, there is a self-reinforcing trend underway of treating screen use as a shorthand for a broad range of parenting choices. Like-minded people find it easier to articulate and then stick to their principles when they build social lives that suggest a coherent view to their children of what is good for them. It’s much easier to withstand the “But Mom! Everyone else has one!” argument when, in fact, their friends do not each have one. Whether we know it or not, building a future for the next generation is always something we do together. This is Amistics, the set of choices we make as intentional cultures and subcultures about the kinds of technologies we are willing to make part of our lives.

If we are to live well with AI, we must recognize and emphasize this level of ethical formation that is neither individual nor universal, not zero-sum but free-range. To act for the common good requires a community that understands its shared ends and goals. We must find ways for politics to enable meaningful decisionmaking to take place in actual communities and cultures, rather than in higher, more abstracted contexts.

We must work to build we where it is missing.

An obvious and critical problem presents itself: If cultures as cohesive as the ones I have just mentioned are the proper units for making decisions about technology, what do we do in contexts where decisions need to be made but the cultural context is inadequate — where “we” may not be coherent enough to make a decision?

For example: Should OpenAI reform or abandon its approach to how ChatGPT, which is available to potentially everyone, reasons about values? Could the Biden administration have produced a less inane executive order on AI? Will even the superintendent of a public school district serve too many masters to have a coherent vision of the purpose of education, and therefore of how to use AI in classrooms?

The AI moment raises anew Aristotle’s warning that a good life is impossible without a good polity. Some of the most fundamental decisions we need to make about AI, including those mentioned above, may be impossible while our politics is in such a woeful state. Some hope lies in the simple truth, emphasized by Yuval Levin in his new book American Covenant, that our constitutional order can provide unity without uniformity or forced agreement. American federalism, polycentricity as analyzed by institutional economics, subsidiarity as presented by Catholic Social Teaching — the issue has long been recognized as essential, which at least means that there are many good ideas about how to address it.

Moving from theory to practice, there are steps that many of us can take toward deliberating about technology from a coherent “we.” To deal with just one crucial case: alignment researchers could cease trying to build a single superwise AI and instead work toward building multiple superwise AIs, each encompassing the wisdom of a single coherent tradition — an Orthodox Jewish superwise AI, a classical liberal superwise AI. Each could even be put in conversation with the others to work toward answers to contentious questions, guided by human representatives of the great traditions. It is not impossible to imagine that genuine advances in moral philosophy and interreligious dialogue could be achieved this way, as AI is already doing in other fields.

This approach would be technical, in part: a chatbot should decline to answer certain moral questions until it identifies the tradition from within which the user wants the question answered. Institutional homes for this technical work are urgently needed. If alignment research wants to be trusted in this task, it cannot be done by Silicon Valley alone, but must be broadly undertaken. Imagine an AI alignment project, or projects, not just funded and carried out by OpenAI but also by the Vatican, the State of Israel, and the Kingdom of Bhutan.

But for most of us, the steps toward building a coherent “we” will be ones we already must take for other reasons — steps toward rebuilding our currently fragmented communities, cultures, and traditions.

We must seek to serve head, heart, and hands.

As much as I have cautioned here that we need a specific “we” before we can answer what we should do with AI, the answers offered by each culture need not always be alien to the other, and often they will have much in common. Most importantly, while answers about the kind of future we want have always varied in their details, what underlies any lasting vision is the correct intuition that the future we are building is one in which our children will be living: our decisions about technology are, ultimately, for (or against) them. This means that I can offer a general sketch here of the kinds of questions that an Amistics framework might urge upon us. We, and our children sooner rather than later, will have to address them.

The Perplexity chatbot can scan a twenty-page uploaded file and, when prompted, give genuinely helpful editorial advice. Is an undergraduate asking AI to give her feedback on an essay just saving time by skipping in-person tutoring at the campus writing center, or is she cheating the system, or even herself, if she blithely accepts its improvements?

ChatGPT now offers “voice mode,” featuring impressively human-sounding interactions — so much so that Scarlett Johansson was justifiably outraged that one of the voices sounded like her own. ChatGPT also powers the “My AI” digital friend offered for free by Snapchat, an app used daily by more than half of American teenagers. Is a teen who shifts from using AI as a tool to thinking of it as a friend and confidant at risk of subtle harm?

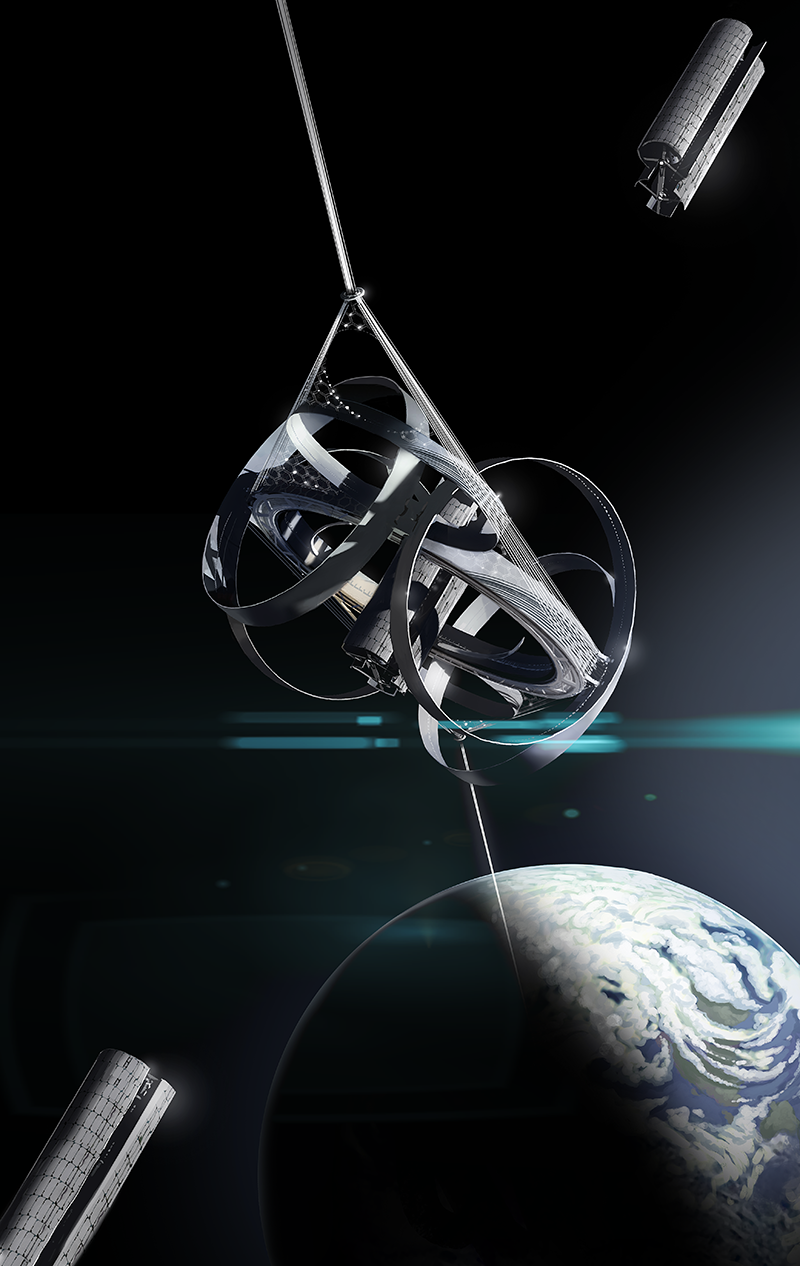

A team at Harvard Business School, in a working paper on the “jagged technological frontier,” argues that competitive productivity in some areas of knowledge work already requires that one adopt the strategy of becoming either a “Centaur,” who divides and delegates some tasks to an AI “half” while remaining fully human in other aspects, or a “Cyborg,” who completely integrates one’s task flow with AI, continually interacting to create a finished product. If we continue to push forward this technological frontier — expanding the set of tasks for which AI assistance or control is economically beneficial — will it aid or hinder our children in actualizing their own capabilities? Will it help them in or impede them from creating a future that still also explores physical frontiers, whether ocean depths or outer space?

These questions are based on a particular pedagogical model: “head, heart, hands” — thinking, loving, and doing. What part will AI have in the formation of our minds, in our relationships to others, and in the work of human hands?

The AI developments to come will require us to re-imagine a whole host of practical realms: formal education; whether the AI assistant on your phone is a servant, a friend, a long-distance lover, or a fiend; whether in your career you will have to become a cyborg or a centaur, or if you can find a way to remain a craftsman. We will each need to make choices. But the way to make our choices stick — for ourselves and especially for our children — is by finding like-minded friends in communities, and linking these communities in a way that allows for a “live and let live” treatment of a range of views.

If our children are to have a future that is genuinely theirs, then they will need to develop their heads, hearts, and hands in ways that allow them to decide which technologies will help them to live well and which will not. For an Amistics of AI to take root, we cannot defer these questions until they are answered definitively by the benevolent superwise “Big Mother” that some AI pioneers hope to create. We human mothers and fathers must ask ourselves and each other “What do we owe to our children?” — and we must be willing to make whatever sacrifices our answer requires.

And if that doesn’t work, we can always hope for a true — and doubtless very different — Sarah Connor.

Keep reading our Summer 2024 issue

The Amish on AI • Why UFOs • Facts vs. us • EA as self-help • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?