You are not my friend, bureaucrat…. I no longer wish to be annoyed by your simpering ways.

On the Great Acceleration Highway, no scenic vista gets more traffic than the prospect of permitting reform, which is predicated on the apparent fact that federal laws and regulations as currently enacted and enforced ensnarl all new meaningful projects in a cost-prohibitive bureaucratic-legal morass. I’ve worked on energy policy for more than a decade and have never seen a permitting reform package as vibrant and viable as the one assembled by Senators John Barrasso (R.–Wyo.) and Joe Manchin (I.–W. Va.) under debate in Washington now. Previous packages may have been more vibrant but procedurally dead, or more viable but boring. Their bill adds permitting deadlines where they don’t exist, expedites them where they already do, and streamlines various processes or modifies them with a general bias toward building stuff. Good.

But I want to tell you a bedtime story about a very specific project that holds a lesson not often mentioned in the “reg reform” debate about how to revamp American infrastructure. The project is the Alaska liquefied natural gas export facility, known as Alaska LNG. No, this is not yet another op-ed about the benefits of LNG exports, from enhancing the energy security of the U.S. alliance system (parts of which rely on Russian gas) to reducing emissions of carbon dioxide relative to burning coal, an obviously meritorious argument that bears no repetition. This is a reflection, maybe even a fable — with a warning.

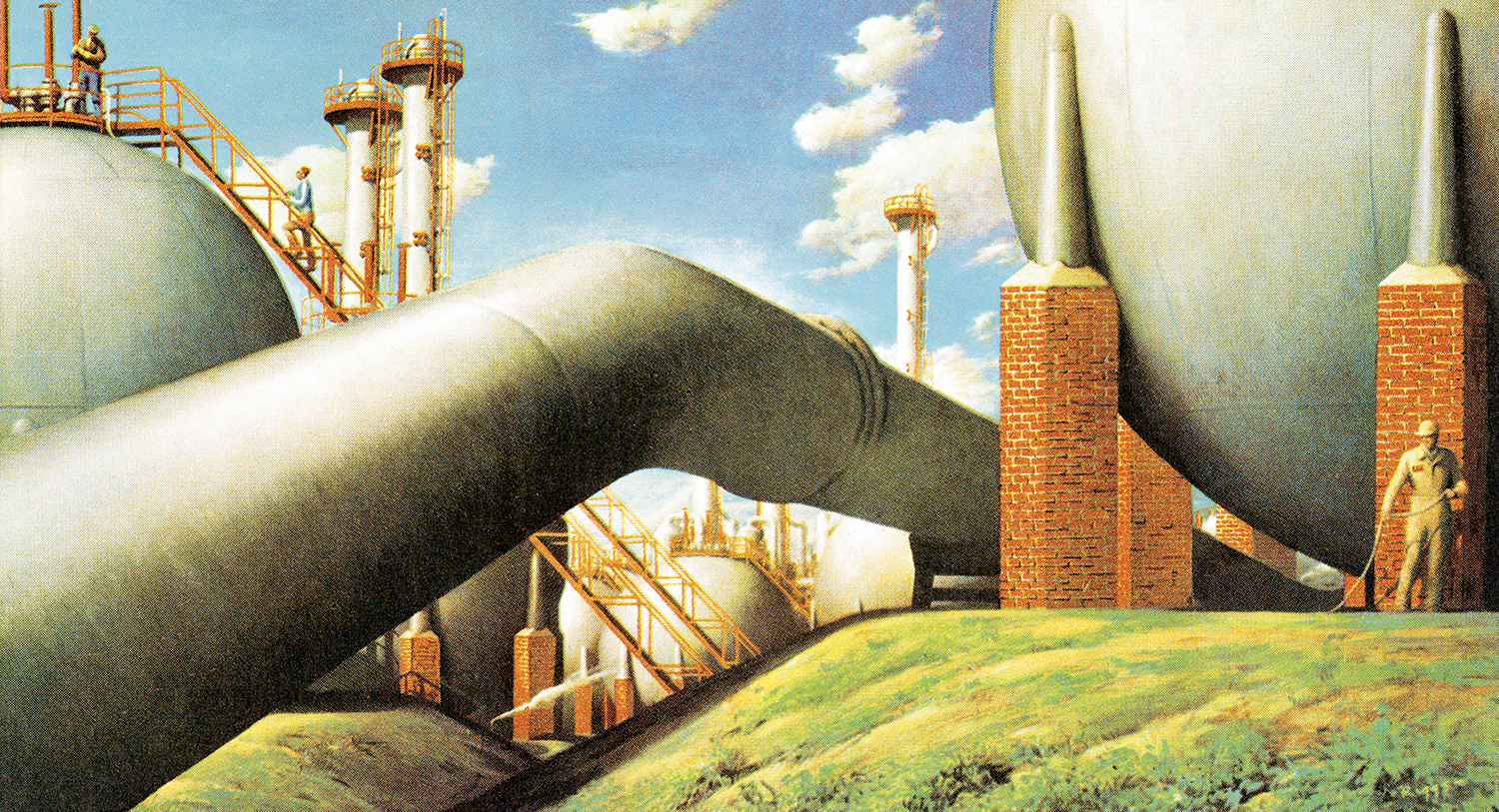

Imagine for a moment that in the northernmost reaches of Alaska, the North Slope, there is a vast reservoir of natural gas stranded for want of infrastructure. Stipulate that we know with one hundred percent certainty that this gas exists and that we can pinpoint its whereabouts without any major exploration required. There is no resource risk — no danger that the first well comes up dry after a multibillion-dollar investment. And an elaborate transportation system is already in place to bring equipment, materials, and people to this remote region. So far, so believable.

Now let your imagination run wild. Stipulate that we have the technical know-how to construct a pipeline that would transport this North Slope natural gas to the southern coast of Alaska, where we also know how to liquefy it, load it onto maritime carriers, and ship it anywhere in the world. Remember that we already move oil around this way! Further stipulate that some of America’s closest allies also support the project, both as financiers and customers.

Here is where the story may begin to look a tad exaggerated. How could such a project ever be permitted? Stipulate the answer: all the major federal permits are already obtained. A series of three presidential administrations, from Barack Obama through Donald Trump to Joe Biden, all either acquiesce or embrace the concept. Further, the State of Alaska fully supports it — in fact, the legislature creates a corporation to get it done — and its geography is contained entirely within the state’s boundaries: no interstate issues whatsoever.

Now the fantasy races to the finish as only fantasies can. The largest LNG export facility ever constructed is complete, a Babelesque testament to the world that America is a place where big things still happen.

Unfortunately, the project does not exist. But why not?

To be sure, nothing except the ending is remotely fantastic. The North Slope is indeed home to an impressive collection of oil companies drilling in the harshest conditions under some of the strictest safety and environmental rules in the world. Workers are flown in, supplies are trucked in, helicopters fly about, and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), a modern marvel, transports crude oil eight hundred miles to the port of Valdez down south.

We know the natural gas exists because it is produced alongside crude oil as “associated gas,” a phenomenon so prevalent the “oil and gas” industry typically is referred to in the singular. However, unlike in other parts of the world that allow natural gas to be vented or flared when infrastructure for tapping it doesn’t exist, Alaska prohibits venting and flaring except for operational safety and emergencies. Without anywhere else to put it, oil companies reinject the gas back into the subsurface, where it actually helps to pressurize oil fields and maintain production levels. Because it is injected, we have a baseline volume that we know — that we know, in the grandest epistemological tradition — exists. (The U.S. Geological Survey estimates many, many trillions of cubic feet exist beyond this minimum value.)

Who are these close American allies? Japan and South Korea, who are “collective defense” treaty allies just as much as any member of NATO. The countries have repeatedly expressed interest in developing the project, both as recipients — in order to diversify their sources of supply for security purposes — and as financing partners.

And the permits? The State of Alaska indeed created the Alaska Gasline Development Corporation, which is the formal applicant for federal authorizations, and no interstate issues exist, in contrast to something like, say, the Keystone XL pipeline, which required approvals from Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska. Despite the predictable opposition from environmental groups (on the grounds that all fossil fuels should be kept in the ground), the Department of Energy has supported the Alaska LNG project across three successive administrations: the Obama administration issued a conditional approval, the Trump administration issued a final approval, and the Biden administration has acted as cheerleader. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has already completed its environmental review and issued a mostly favorable report.

And yet there is no project to speak of. It exists only on paper. One problem is the fluctuating price tag, which appears to have peaked pre-Covid at around $65 billion and now hovers around $40 billion. Another is the highly idiosyncratic political landscape in Alaska, which doesn’t have either a sales tax or an income tax, funds the state government largely on oil revenue, and in recent years elected an independent governor, Bill Walker (2014–2018), who proposed a tax on natural gas reserves. Japan and South Korea have also become unenthusiastic about the project, citing its prolonged timeline as a major reason.

Federal permitting has not been easy. It contributes to that price tag, which undoubtedly has knock-on effects in state politics and corporate decision-making. Still, the conclusion seems inescapable: even with the tightest deadlines, and with any of the grab bag of regulatory reforms that are favored by make-America-build-again advocates, and occasionally even adopted — a “one-stop shop” for permits, “a single federal document,” expedited reviews — natural gas would still be stranded on the North Slope. The reasons may be unique to Alaska, but any major project of this scale in any other state would face a set of challenges equally unique to its specific circumstances.

Getting federal permitting to a place where it no longer blocks building stuff is a worthy goal. It is necessary, but not sufficient, as the philosophers would say. That is because removing the roadblock isn’t what makes everybody accelerate. As John Maynard Keynes argued, it is the “animal spirits” — the “spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction” — that pushes the pedal.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?