A response to “How to Fix Social Media” by Nicholas Carr

The moment I finished reading an advance copy of Nicholas Carr’s excellent essay, I asked the editors of The New Atlantis if I could assign it to my Boston College students before the online publication date. They said yes, and at long last, I was able to give my class a cogent, lucid, eloquent short history of media regulation in the land of free speech and the First Amendment. Their reactions ranged from “This is fascinating” to “Did the federal government really shut down a radio station for selling goat testicles?”

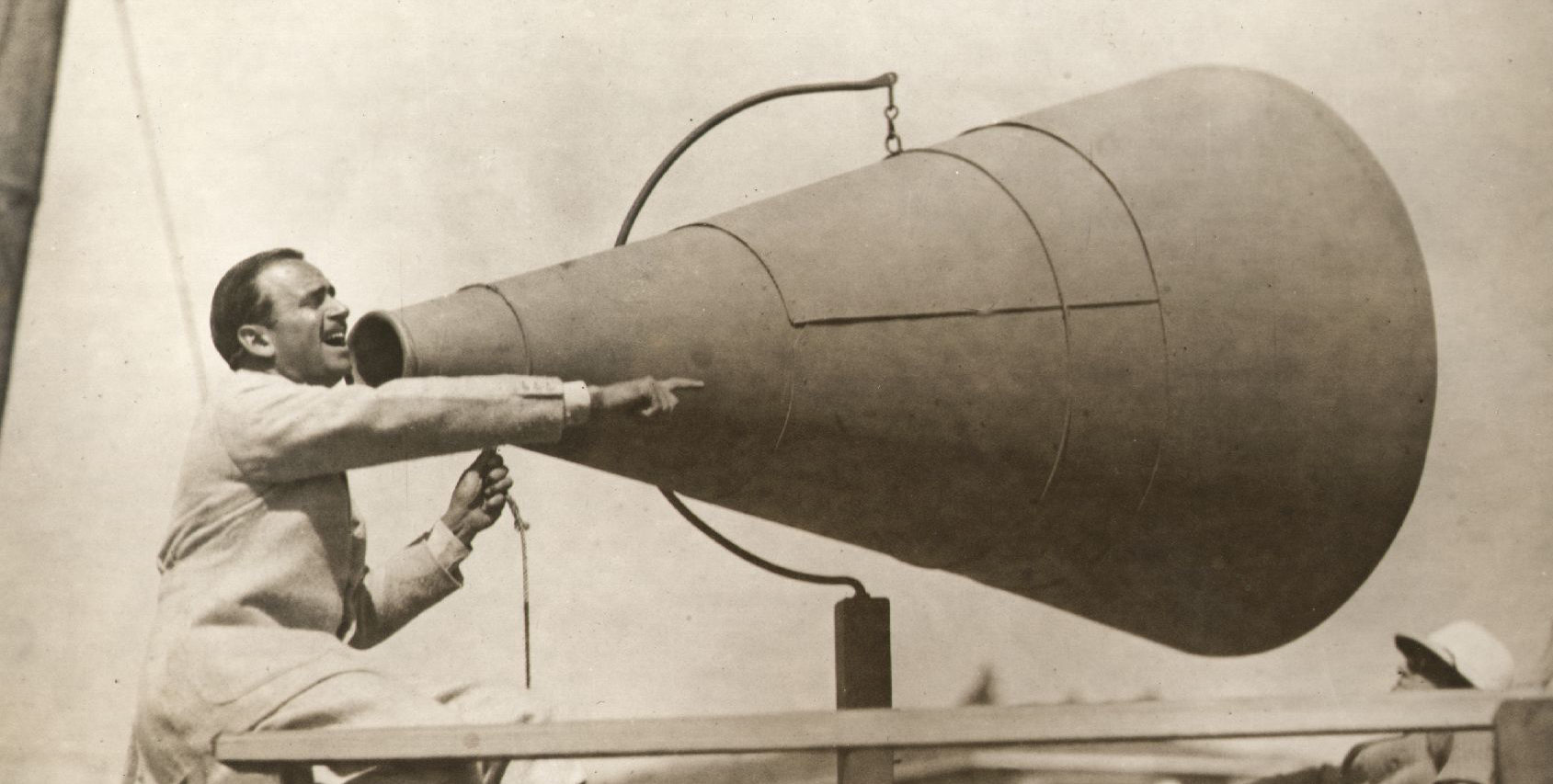

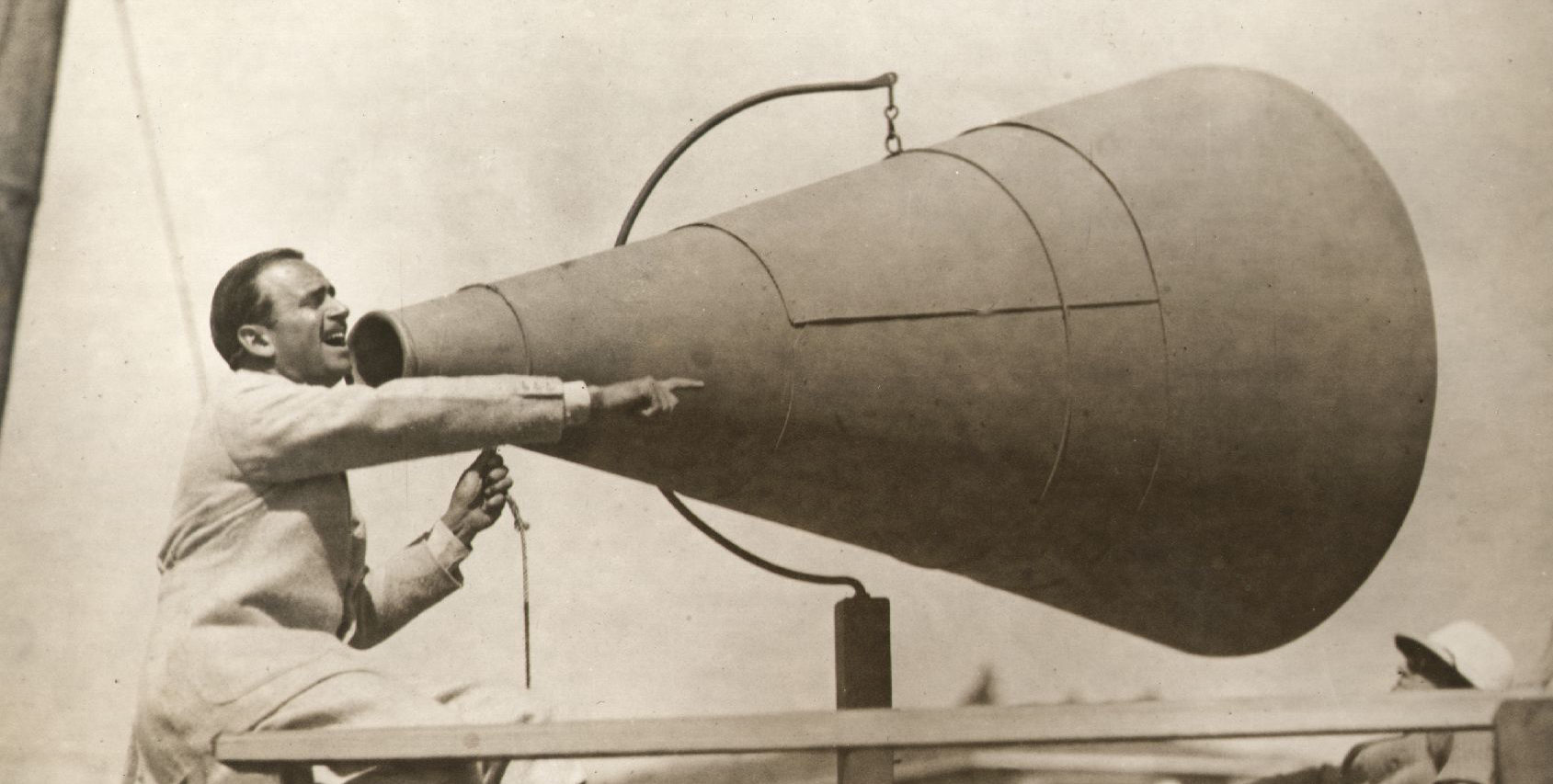

The answer to that question is yes. As Carr writes, “a doctor named John Brinkley, who had made a fortune transplanting goat testicles into men as a treatment for impotence,” started his own radio station in 1923 “to promote a variety of quack treatments.” In 1930, the Federal Radio Commission (precursor to the FCC) “stripped Brinkley of his broadcasting license, ruling that his programming ‘is inimical to the public health and safety.’”

Today we have the Internet, and goat testicles are everywhere. Or so I assume, being understandably reluctant to google the phrase. And more may be in the offing, as Mark Zuckerberg seeks to herd his three billion users into a deceptively green pasture called “the metaverse,” where troubles will melt like lemon drops (he says) and so will pesky politicians (he hopes). On his blog, Carr sums up the metaverse with his usual pith: “Facebook, it’s now widely accepted, has been a calamity for the world. The obvious solution, most people would agree, is to get rid of Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg has a different idea: Get rid of the world.”

Carr has been puncturing the pretensions of Big Tech since the early 2000s, so when he publishes an essay called “How to Fix Social Media,” a lot of people are going to read it. Unfortunately, my students were correct when they observed that, despite the upbeat title, this essay does not tell us how to fix social media.

Instead, Carr highlights two vital principles shaping the history of U.S. media regulation: the secrecy-of-correspondence doctrine protecting private communications between individuals, and the public interest standard governing communications aimed at the general population. And he urges the adoption of these principles by political actors seeking to reform the 25-year-old legal regime under which a handful of Silicon Valley companies have been able to “set their own rules” and grow humongous enough to “wield control over public and private communications” throughout much of the world.

That legal regime is Section 230 of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, whose central clause law professor Jeff Kosseff describes as “the twenty-six words that created the Internet.” Drawing on the precedent of the bookseller, Section 230 defined the Lilliputian ancestors of today’s Brobdingnagian companies as merely intermediaries rather than publishers, meaning they cannot be held liable for any objectionable material posted on their sites. At the same time, Section 230 allows, even encourages, those intermediaries to censor any user-generated content they do not want to see on their platforms, “whether or not such material is constitutionally protected” (emphasis added).

Carr’s focus on long-established principles is what makes this essay so good — and so necessary, because most Americans know little of the history it relates. Indeed, our default position tends to be that the First Amendment forbids all restriction on expression, especially by government, on the ground that censorship is perforce the first step toward tyranny. When by chance we discover that literature, art, and film were legally censored until the mid-twentieth century, and that broadcast radio and TV are still regulated by the FCC, we are surprised.

Nonetheless, a wide spectrum of Americans have begun looking askance at the Big Tech business model that offers “free” services calculated to glue users to their screens, sucks up every particle of their personal data, and sells it not just to advertisers but to bad actors of all stripes, including agents of hostile foreign governments. Big Tech is also in the political crosshairs for allowing the public forum where the nation conducts its business to be engulfed by a nonstop tsunami of disinformation, misinformation, obscenity, vitriol, and violence.

Having seen all this coming for years, Carr proposes a “Digital Communications Act” that would replace Section 230 with a new legal regime that would respect privacy in the form of controls on the use of data, and uphold the public interest by “reinvigorating” oversight by the FCC or some other government agency. As noted above, Carr does not really explain how this fix is supposed to work. But we cannot fault him for this, because the fact is, he does not know. And neither does anyone else.

The current reform buzz in America consists of three strategies. The first is to keep the immunity part of Section 230, but scrap the part that gives companies a free hand to censor. The second is to declare Big Tech a natural monopoly, like the water supply, and regulate it accordingly. Both have serious drawbacks, so the best approach may be the third: to revive the pre-1990s doctrine of antitrust law as a much-needed bludgeon to break up concentrations of economic power before they can turn into more dangerous concentrations of political power.

While these strategies are being debated, two Brobdingnagian challenges loom. One is the oceanic size and velocity of the data flow, compared to the picayune resources, both human and automated, to “moderate” it. To cite just one example, TikTok recently reported that in the second quarter of 2021, it scrubbed more than 81 million videos for violating its community guidelines (or terms of service). This sounds impressive, but it was less than one percent of the videos posted that quarter.

Second is the fact, lost on millions of citizens who have never ventured outside the American bubble, that Big Tech strides the narrow world like a colossus. About 88 percent of Facebook’s users live outside the United States and Canada — and this is not counting China, which banned Facebook in 2009. This global dimension raises profound jurisdictional questions that have yet to be answered. When Big Tech firms comply with repressive speech laws in authoritarian countries, they are denounced by human rights organizations. When they assume American-style liberties in other democracies, they collide with the fact that on this planet the First Amendment and Section 230 are no more than local ordinances (to adapt a line from a 2014 Harvard Law Review piece).

To my students, these cautionary notes may sound like admiring the problem instead of solving the problem. Who can blame them for preferring the latter? But the only way to fix a problem is to admire it, goat testicles and all, for a good long time. And that is what Nicholas Carr has been doing. If he is worried that both versions of Big Tech — the Silicon Valley version and the Shenzhen version — are planning to turn us humans into frictionless avatars who play at freedom while our meat-space selves are treated like Uyghurs, then so am I.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?