This essay is accompanied by the New Atlantis critical edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment.”

The Fountain of Youth, were it ever found or invented, would be radically disruptive of the natural order, distorting the effects of time — perhaps even defying death. But the desire for the fresh feeling of youth and energy is as natural as the forces that erode it. And it would be unnatural not to balk at the abyss of death — if not our own annihilation, then the unfathomable loss of loved ones.

In his 1837 story “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment,” Nathaniel Hawthorne exaggerates this dilemma to the point of farce. Four buffoonish ne’er-do-wells at the end of their years are gathered together in the home of “that very singular man, old Dr. Heidegger…. whose eccentricity had become the nucleus for a thousand fantastic stories.” His study, where the visitors assemble, is “a dim, old-fashioned chamber, festooned with cobwebs, and besprinkled with antique dust,” a spooky lair at once scientific and magical:

Over the central bookcase was a bronze bust of Hippocrates, with which according to some authorities Dr. Heidegger was accustomed to hold consultations, in all difficult cases of his practice. In the obscurest corner of the room stood a tall and narrow oaken closet, with its door ajar, within which doubtfully appeared a skeleton. Between two of the bookcases hung a looking-glass, presenting its high and dusty plate within a tarnished gilt frame. Among many wonderful stories related of this mirror, it was fabled that the spirits of all the doctor’s deceased patients dwelt within its verge, and would stare him in the face whenever he looked thitherward.

Dr. Heidegger asks his guests for their help with “an exceedingly curious experiment,” which they expect to be “nothing more wonderful than the murder of a mouse in an air-pump, or the examination of a cobweb by the microscope, or some similar nonsense, with which he was constantly in the habit of pestering his intimates.” But this time, he has something else in store. Taking a desiccated rose that has lain in the pages of his spellbook for more than fifty years, he dips it in a vase of water and restores the flower to life.

The water, he tells his friends, is taken from the Fountain of Youth that Ponce De Leon and countless other adventurers once sought. They never found it, Dr. Heidegger explains, because “its source is overshadowed by several gigantic magnolias” — but an unnamed acquaintance of Heidegger’s knew of its whereabouts and bottled some of the fabled water for him to study.

Notwithstanding the rose’s resurrection, the visitors — a bankrupt businessman, a dishonored soldier, a disgraced politician, and a withered beauty — are uniformly unimpressed. “They were all melancholy old creatures, who had been unfortunate in life, and whose greatest misfortune it was, that they were not long ago in their graves.” The first is Mr. Medbourne, who “in the vigor of his age, had been a prosperous merchant, but had lost his all by a frantic speculation, and was now little better than a mendicant.” Presumably, he once provided some sort of product or service, but in greed abandoned that constructive contribution in favor of dubious speculation: using money to make money.

The next man, Colonel Killigrew, “had wasted his best years, and his health and substance, in the pursuit of sinful pleasures, which had given birth to a brood of pains, such as the gout, and divers other torments of soul and body.” Killigrew is an old soldier; the body that once served God and country — bringing him rank, perhaps a bit of glory, and certainly his share of “sinful pleasures” — now fails him.

The other man, Mr. Gascoigne, “was a ruined politician, a man of evil fame, or at least had been so, till time had buried him from the knowledge of the present generation, and made him obscure instead of infamous.” To be “ruined,” Gascoigne must once have had an honorable reputation to spoil in the first place. Now, he has not even the benefit of infamy. He is a politician without a polity.

All three decrepit “white-bearded gentlemen” were long ago the suitors of the fourth guest, Clara Wycherly, “and had once been on the point of cutting each other’s throats for her sake.” Now known as the Widow Wycherly, “tradition tells us that she was a great beauty in her day; but, for a long while past, she had lived in deep seclusion, on account of certain scandalous stories which had prejudiced the gentry of the town against her.” Nothing more is said about these rumors, or her late husband, if indeed she had one: “Widow” may simply be a polite or knowing way of hinting at the scandal. She is the only one of the four with a first name (later revealed by the Colonel, in a moment of excessive familiarity) and the one who best understands the appeal of the strange elixir.

The men in this story have or once had titles — the only kind to be obtained in a democracy, those based on what one does. Heidegger is a doctor, Killigrew is a colonel, Gascoigne once held the title of his office, and Medbourne hung his own shingle. Clara’s title is simply Widow. Her identity and reputation originate less with what she does than with what she is. Her feminine excellence lies in preserving her beauty and virtue. Men, she knows, are inclined to forgive the lack of one if there is enough of the other, but she lost both long ago. Like an aging movie star, Clara’s life is her look; she has watched and marked every gray hair, wrinkle, and crow’s foot. When Heidegger asks if they think the rose could ever bloom again, Clara responds with a “peevish toss of her head.” “Nonsense!” she complains. “You might as well ask whether an old woman’s wrinkled face could ever bloom again.”

Nonetheless, the promise of the elixir is sufficiently compelling that when Heidegger invites them to try it for themselves, they all accept: “though utter skeptics as to its rejuvenescent power, they were inclined to swallow it at once.” The spheres of life that these four figures represent — commerce, war, politics, and sex — each carry a certain urgency, an energy and drama born of the fact that life will one day end. If one always has tomorrow to do things differently, the choices made today do not matter. One need not cultivate the excellences proper to one’s position or profession, as these figures failed to do. By restoring their wasted youth, the potion offers them forgiveness without repentance, a second chance to spend as they had spent the first.

Heidegger urges them to avoid this outcome, suggesting that they strive to recall the lessons that they ought to have drawn from their sordid lives:

“Before you drink, my respectable old friends,” said he, “it would be well that, with the experience of a life-time to direct you, you should draw up a few general rules for your guidance, in passing a second time through the perils of youth. Think what a sin and shame it would be, if, with your peculiar advantages, you should not become patterns of virtue and wisdom to all the young people of the age!”

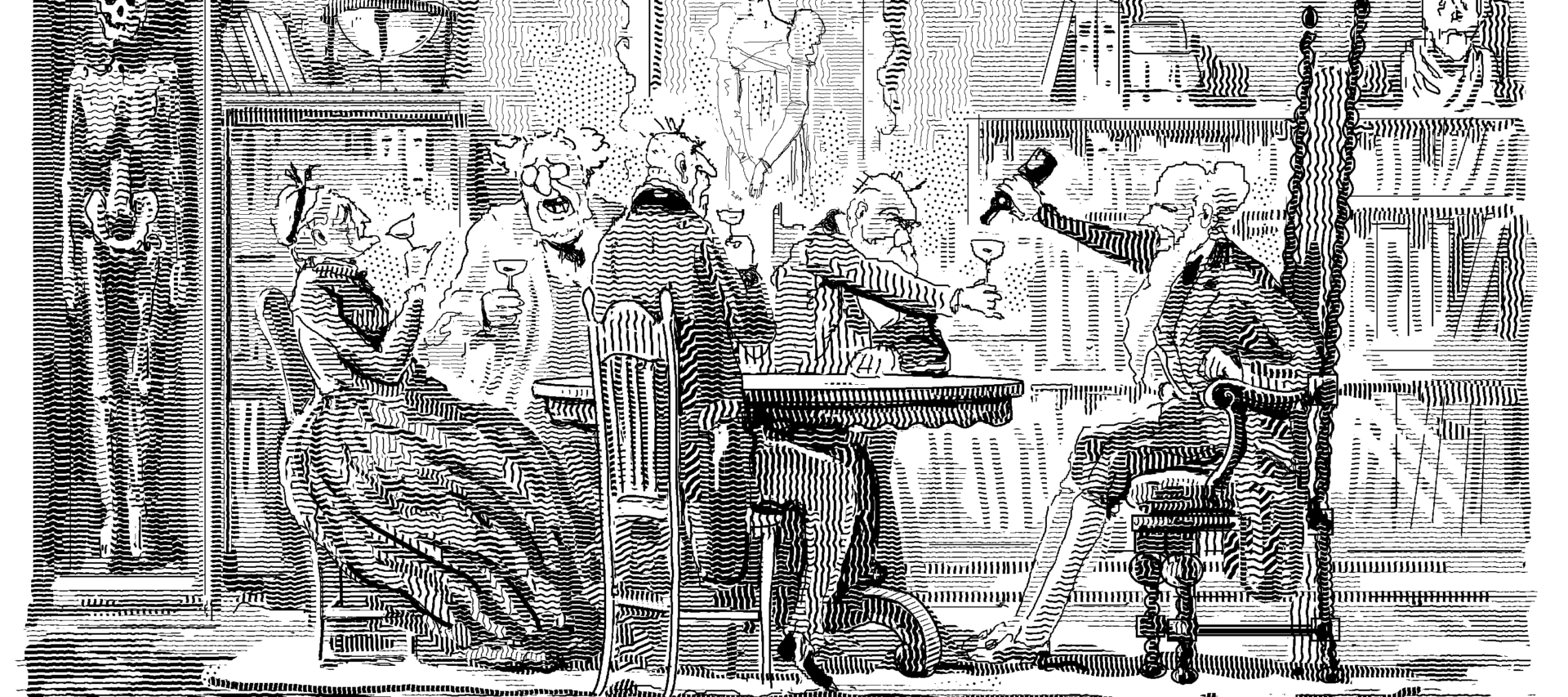

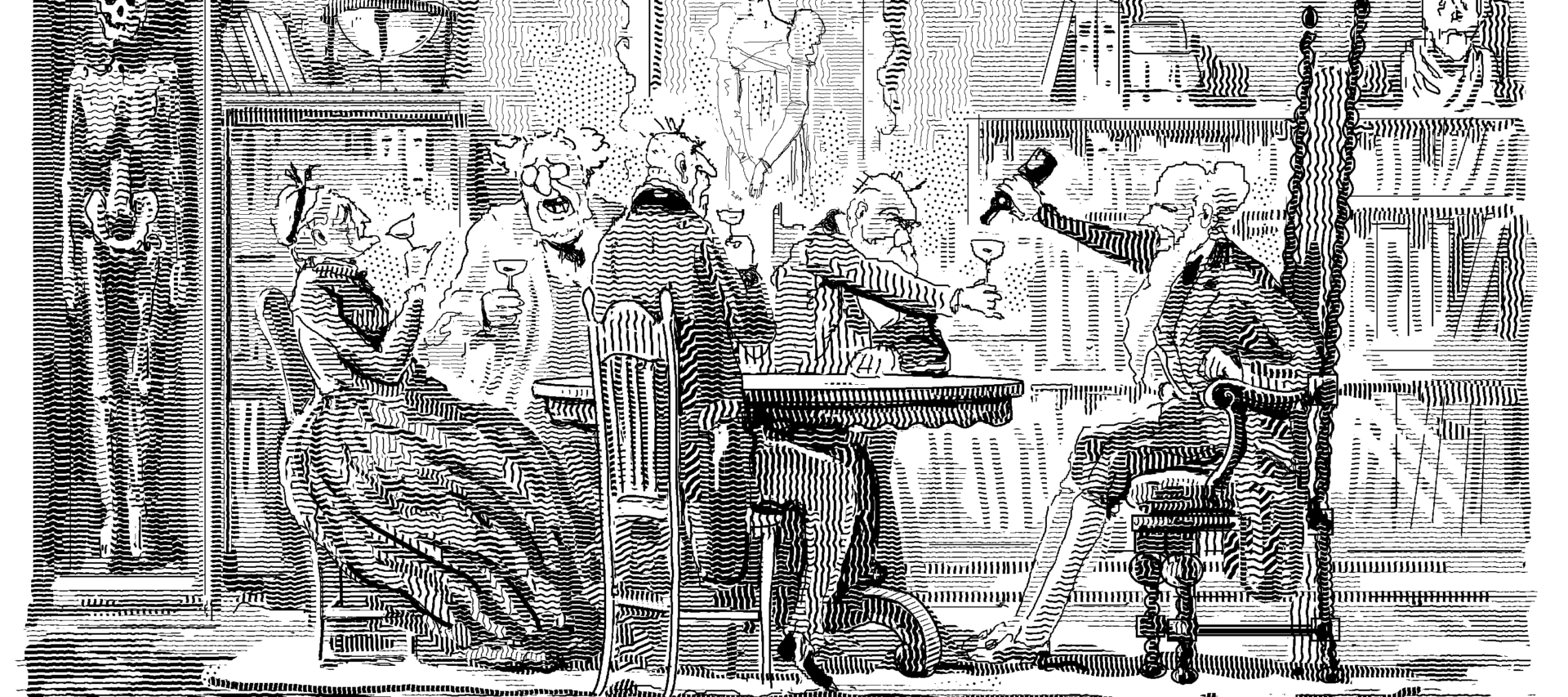

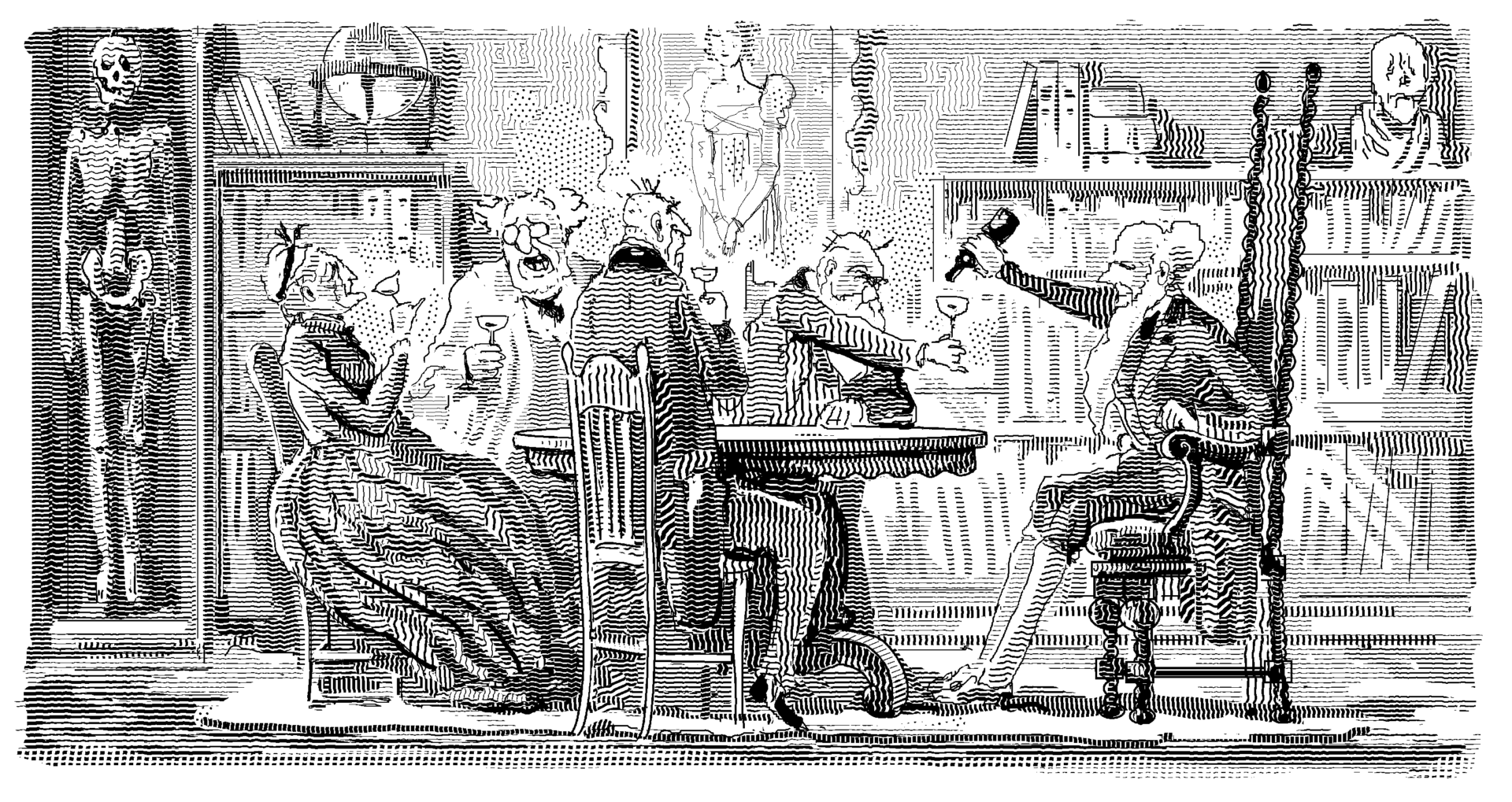

Their “peculiar advantages” stem from their closeness to death and eternity; Heidegger advises them to bring some sense of the eternal truths, or at least “a few general rules,” to bear on the pressing, everyday spheres that they represent — not to carry on indefinitely, but to learn to live life in the present better. But this admonition is lost on the assembled guests, who begin to knock back successive draughts, and to their astonishment become young once again. The Widow Wycherly prances delightedly before her image in the mirror, Colonel Killigrew breaks forth into “a jolly bottle song,” Mr. Medbourne whips up a silly shipping scheme, and Mr. Gascoigne mutters conspiratorially to himself “some perilous stuff or other, in a sly and doubtful whisper, so cautiously that even his own conscience could scarcely catch the secret.”

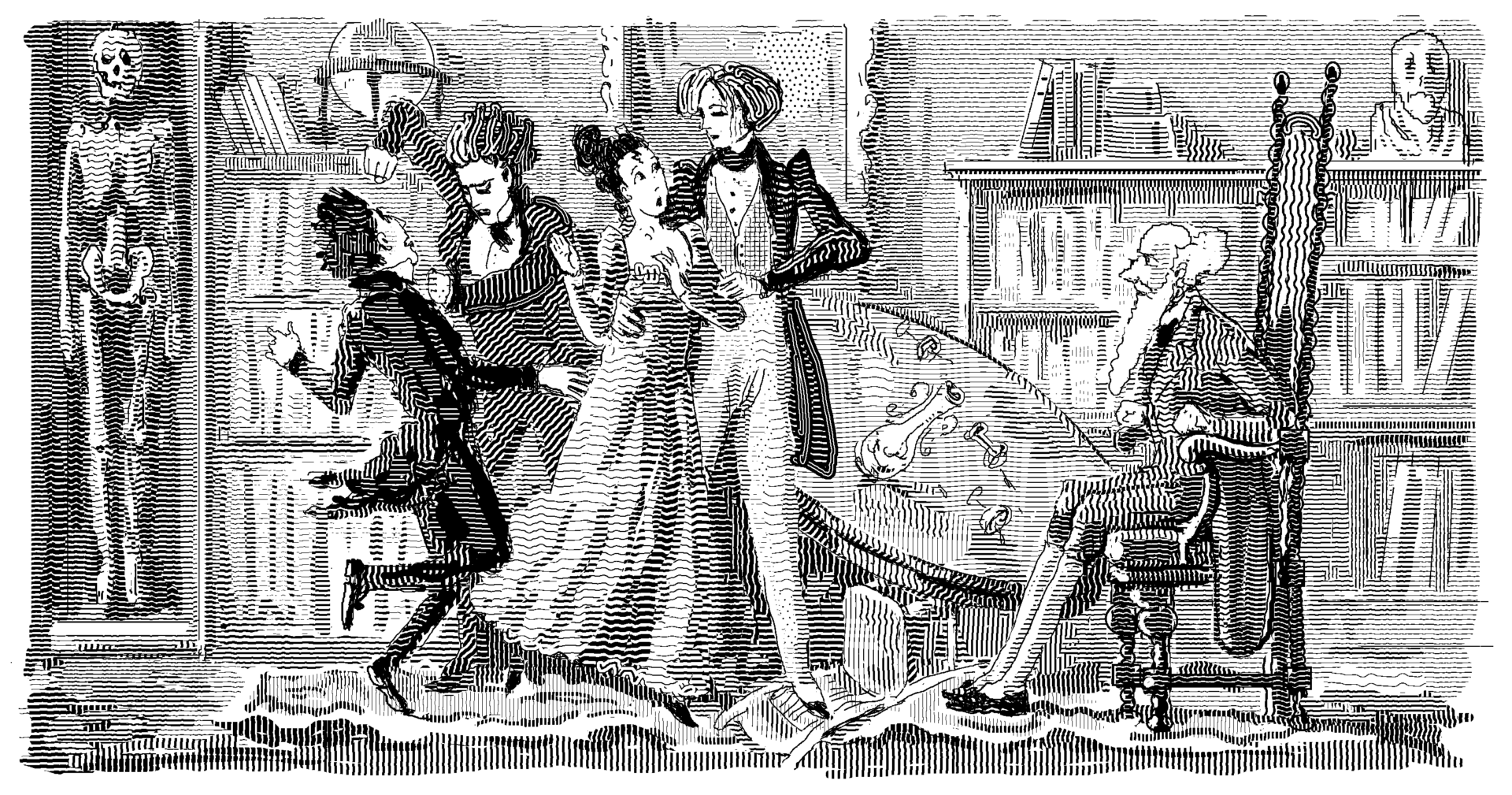

As they grow younger still, the elixir unleashes the latent impulses of these unrepentants. Finally noticing each other, regressing from solipsism to selfishness, they bounce around the room together, callously mocking the still-ancient Dr. Heidegger, afflicted with “the infirmity and decrepitude of which they had so lately been the victims.” The men each play to type as they try to win Clara for a dance. The warrior issues an order: “Dance with me, Clara!” The politician pulls rank: “No, no, I will be her partner!” The merchant invokes contract: “She promised me her hand, fifty years ago!” Mirth turns to madness: A playful scuffle for the lady soon becomes a fight, as they renew their near-murderous competition for the now-restored beauty. “Yet, by a strange deception, owing to the duskiness of the chamber, and the antique dresses which they still wore, the tall mirror is said to have reflected the figures of the three old, gray, withered grandsires, ridiculously contending for the skinny ugliness of a shrivelled grandam.”

Flying at each other’s throats, they knock the table over and dash the vase to the floor. The precious water flows away. “They stood still and shivered; for it seemed as if gray Time were calling them back from their sunny youth, far down into the chill and darksome vale of years.” The transience of the water’s power is revealed, and the quartet, having squandered a second youth, finds itself old once more.

Dr. Heidegger, who has sat quietly throughout the incident, only refilling glasses and “watching the experiment with a philosophic coolness,” now pronounces his conclusion:

“Yes, friends, ye are old again,” said Dr. Heidegger, “and lo! the Water of Youth is all lavished on the ground. Well — I bemoan it not; for if the fountain gushed at my very doorstep, I would not stoop to bathe my lips in it — no, though its delirium were for years instead of moments. Such is the lesson ye have taught me!”

But, unmoved from their fruitless quest to kill time before time kills them, “the doctor’s four friends had taught no such lesson to themselves. They resolved forthwith to make a pilgrimage to Florida, and quaff at morning, noon, and night, from the Fountain of Youth.”

Not only was the great lesson lost on them, but so were the simple facts of the experience. It seems clear that Heidegger himself invented the elixir. While the Fountain of Youth may be hard to find, the idea that a bunch of overgrown flowers have successfully hidden it from every Ponce De Leon who has sought it, only to be revealed to Heidegger’s disinterested friend, is preposterous. Such a worldly group of individuals ought especially to know better. Their initial skeptical response to Heidegger’s rose demonstration — to reply “carelessly,” to note its “pretty deception,” and to recall having “witnessed greater miracles at a conjurer’s show” — was worldly-wise.

In fact, Heidegger’s experiment proceeds much as a magic show might: one part showmanship, one part misdirection, and a little help from science. It begins with a small demonstration — the rose trick — that serves to set up the subsequent illusion. Heidegger’s prefatory story is simply a magician’s patter, designed to pacify the skeptical observer and distract a believing audience while the illusion is prepared. While it would only be natural to inquire about the potion’s origin, its provenance is immaterial to the experiment at hand. His subjects can believe or disbelieve the origin story. What matters is where the waters lead them. The prospect of what the elixir can do overcomes sensible skepticism; it even overcomes wonderment, moving directly to desire. Heidegger leaves his audience wanting more, while he conceals the true wellsprings.

Heidegger himself, though, seems to want no further part of his invention. He has discovered how to beat back the aging process, but he understands that such a victory is fleeting. If youth, as the saying goes, is wasted on the young, then it seems that eternal youth can be wasted even on the old. Seeing imperfect human nature revealed in his subjects, he grasps the danger in removing the urgencies of time and death from life and vows never to partake of his own invention. Unlike some of Hawthorne’s other scientific geniuses, Heidegger seems to be a harmless magician of great talent, almost a model of restraint amid science’s fantastic power. Almost.

Hawthorne’s fable can be read as a plea for scientific and technological responsibility. One might interpret Heidegger’s categorical refusal to drink the water as the final flourish of his carefully planned trick: the revelation that the second chances offered by the potion were never more than an illusion, and the implication that overambitious scientific inquiry and technological innovation can only come to no good. But Heidegger’s voice ought not to be confused with Hawthorne’s. The author’s own trick — his “prestige,” in the parlance of magicians — lies in the secret of the rose.

The old rose was given to Heidegger by his fiancée, Sylvia Ward, who did not live to see her wedding day. “Above half a century ago, Dr. Heidegger had been on the point of marriage with this young lady; but, being affected with some slight disorder, she had swallowed one of her lover’s prescriptions, and died on the bridal evening.” A large portrait of her hangs on the wall, gazing down on the proceedings as if in silent reminder that Heidegger, more than any of his guests, might benefit from the Water of Life. Indeed, it seems that he has labored all those many decades to produce it, while the rose lay at the center of his spellbook as the emblem of his purpose. But when the water spills and the blooming flower, too, returns to its dry death, he does not count it as a loss: “‛I love it as well thus as in its dewy freshness,’ observed he, pressing the withered rose to his withered lips.”

Consider Heidegger’s room, the “very curious place” that the miracle of the rose is designed to make the onlooker forget. If the chamber is “festooned with cobwebs, and besprinkled with antique dust,” the room rarely holds people or expects them. The real work must take place elsewhere, which leads one to ask what manner of work the good doctor is involved in. He literally has skeletons in his closets, ghosts in his mirrors, and a book of magic on his desk; “and once, when a chambermaid had lifted it, merely to brush away the dust, the skeleton had rattled in its closet, the picture of the young lady had stepped one foot upon the floor, and several ghastly faces had peeped forth from the mirror; while the brazen head of Hippocrates frowned, and said — ‛Forbear!’”

There are secrets in this house, not least the secret of what exactly happened on the night Sylvia died. As he retells the story to his guests, Heidegger conveniently omits the fact that it was his concoction that killed her. Perhaps the visitors already knew the troubling circumstances, but if so, one would expect him to show some remorse or sadness. He tells the story “with a sigh,” but the sigh is ambiguous. For Heidegger, the blame for Sylvia’s death does not lie with his own malpractice but with the grim fact of mortality itself. Like his “unfortunate” subjects, Heidegger has been on his own quest to avoid atoning for past wrongs. Whatever happened that fateful evening, Heidegger felt responsible enough to commit to a solitary, fifty-five-year struggle to understand life and death and to bottle their secret for human consumption. Instead of, perhaps, seeking forgiveness for his part in the accident or devoting his considerable talents more towards curing the sick, Heidegger set to work attempting to erase the crime — not his own misdeed, but what he considers the true crime: the injustice of losing a loved one. The “book of magic” may be nothing more than a collection of diagrams of dissected creatures, formulas for possible concoctions, and notes about test runs on plants, animals, and whatever else Heidegger used as his quest drove him. Unmarked and secret, it gains a reputation for being magical, as any sufficiently advanced science begins to resemble.

Somewhere along the way, however, Heidegger began to see life as an emergent effect of processes that, though mysterious, are capable of being described, predicted, and controlled. It is there that he loses his way. Of all the items in the doctor’s study, perhaps the most macabre — even more so than the four “corpse-like” creatures — is the undead Dr. Heidegger himself, who has taken on the visage of impassive Father Time. His subjects, who expect “nothing more wonderful than the murder of a mouse in an air-pump,” in this case are themselves the murdered mice. The true experiment is not the physical test of the potion but the anthropological study of the company’s response. Heidegger observes the experiment with “philosophic coolness,” a screen of objectivity that also lets him hide from the exigencies of life and death. Heidegger fully expects his experiment to reveal human fallibility — so that it might excuse his own weaknesses. His declaration of love for the rose is not a show of humility; it is the arrogance of a man who has succeeded where his subjects have failed.

For Heidegger has not just invented a rejuvenating potion; he’s invented a resurrection potion. The rose, after all, was not just old, but dead, a fact easily forgotten when Heidegger misdirects the observer’s focus to the potion’s beautifying effects. Heidegger has not only harnessed eternal youth but eternal life.

In order to attain that power, Heidegger becomes objective — consummately and yet perversely objective. Human life and its meager concerns are, to him, things to be shaken off, impediments to a stoic acceptance of our fate. Instead of rushing his rose to new water that it might bloom, he shakes off “the few drops of moisture” still remaining, killing it again. Here is a man with power over life and death who stands idly by while the beautiful and the fragile, together with the wicked and the ugly, perish. Heidegger sees only the accidents of a deterministic universe for which no one in particular is responsible. This is the great lesson confirmed for Heidegger in his experiment.

At least, this is the lesson that he wishes to confirm: that it does not matter that he failed in what he first set out to do, to bring his lover back to life. There is no real resurrection water, only one that mimics its effects for a few minutes. It is not good for much of anything except the kind of farce that Dr. Heidegger has staged. In selecting subjects whom he knows will display the maximum amount of folly, Heidegger has rigged his experiment; he knows in advance that it will prove to him that everyone is better off for his not having invented the true Water of Life. And perhaps they are.

But at some point, having given up that aim, he chose to devote himself to the illusion of it, neglecting other good that he could do. He exhibits an inhuman coldness in his reluctance to fellowship with others except to show them up — a coldness calculated to match that of the universe itself, which one way or another ultimately claims all lives. To be indifferent to our powerlessness against this loss is to claim a certain power over it.

But, though Time is unforgiving, there are other, better ways to accept our place in it. It is notable that no one in the story apparently has children. Giving life to others instead of grasping after it ourselves is one way of transcending mortality. And offering comfort instead of ridicule to those around us softens the brutality of errors that cannot be undone and losses that can never be reclaimed. We do not have forever, but, for a while, we do have each other.