Where there is no vision, the people perish.

– Proverbs 29:18

America now has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to open the space frontier by initiating a sustained program of human exploration of Mars. Elon Musk’s SpaceX Starship launch system will soon be operational, offering payload delivery capability comparable to a Saturn V Moon rocket at about five percent of the cost. Musk has positioned himself close to President Donald Trump, who at his inauguration in January promised that his administration would be “launching American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars.” As far as meeting the central political and technical conditions for making a bold reach to the Red Planet are concerned, it’s game on.

There are, however, several problems. First and foremost, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the government agency that one would expect to lead such an endeavor, is currently not competent to do so. And while SpaceX is far more competent, it should not be put into the position of executing a Mars mission alone, as some would like. NASA needs to be leading the effort because America should go to Mars, not just a private space enterprise. But to effectively lead human space exploration, NASA first needs to be fixed.

The NASA of the 1960s did a brilliant job leading the Apollo project, which, starting from near-zero spaceflight capability, got men to the Moon within eight years of program start. In contrast, despite possessing vastly superior material and technical resources and more than six decades of human spaceflight experience, the NASA of today has made a total mess of its Artemis lunar effort.

Following President Kennedy’s 1961 directive to get men to the Moon within the decade, the Apollo leadership developed a solid plan to conduct lunar missions, identified a coherent set of hardware elements to implement that plan, and proceeded to develop all the technologies needed to create those flight systems. These included large liquid-fueled rocket engines, multi-staged heavy-lift launch vehicles, in-space rendezvous, life support, power, lunar landing, spacesuits, reentry systems, and deep space communication and navigation technologies. The flight systems, which all fit together and interfaced nicely because they were planned in advance to do so, were then built and eleven piloted missions flown, with six actually reaching the lunar surface. Not only that, but all this was done between 1961 to 1973 — along with building and launching the Skylab space station and flying several dozen lunar and planetary robotic probes — on an average inflation-adjusted budget no greater than NASA’s budget is today, roughly $25 billion per year.

In contrast, while it has now been seven years since President Trump announced the start of what eventually became the Artemis program, we have not returned to the Moon. Instead of implementing a clear plan, NASA has supported a random set of expensive projects to develop an assortment of flight systems that simply do not fit together. The SLS launch vehicle upper stage is the wrong size for its lower stage. The Orion capsule — NASA’s crewed spacecraft — is too heavy for the SLS to deliver into low lunar orbit with enough propellant to come home, even by itself, let alone with a lunar excursion vehicle added on. This is because of a design change from one powerful engine, which NASA once considered “critical to the development of the Space Launch System,” to four less powerful ones that don’t add up to the same amount of thrust. The SpaceX Starship, whose adaptation as a lunar lander NASA is also funding, makes both the SLS and the Orion capsule unnecessary, but they must be used by all missions anyway to make their makers happy.

This is quite unfortunate, since the SLS is projected to have a launch rate of only one every year or two, compared to an average two launches per year of the Apollo program’s Saturn V. Starship would be an excellent choice for Artemis’s primary launch vehicle. But NASA did not assign it to that role. Instead they funded it to serve as the program’s lunar human landing and ascent system, a task for which its 100-ton dry mass makes it seriously suboptimal compared to the Apollo Lunar Excursion Module’s 2-ton ascent stage.

The problem gets worse. In competition with the $2.9 billion NASA contract that SpaceX won for its Starship lunar lander in 2021, the “National Team,” consisting of Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, Draper Labs, Boeing, and some other companies, offered to develop a small hydrogen/oxygen propelled lunar landing and ascent vehicle for $5.9 billion. Since they were offering less capability for twice the money, the National Team lost. This did not suit the National Team, however, and they used their political clout to demand they get a contract too, which they did for $3.4 billion in 2023. But given that NASA was already funding the methane/oxygen-propelled Starship, it could have insisted that the National Team design be changed to be a using methane/oxygen propulsion as well. Had they done this, the National Team lander could have operated as a refuellable small ferry, taking astronauts down to and up from the lunar surface from a tanker Starship stationed in low lunar orbit. This would have increased the number of lunar exploration sorties supportable per Starship launch by an order of magnitude. However, since the primary purpose of the National Team contract was to please the National Team and its political supporters by throwing cash their way, NASA chose to prioritize vendor satisfaction over hardware utility and is now paying billions for an incompatible lander.

In addition to this, NASA’s plan, if it can be called that, also includes spending billions to build a space station in high lunar orbit. It is officially called the Gateway — more informally, the Tollbooth. This station adds nothing to the Artemis program’s overall capability. Quite the contrary: If the mission is being done using Starship as the landing and ascent system, a lunar mission will require something like fourteen Starship launches to support a single sortie to the lunar surface if it must go there via the Gateway, but only ten if mission planners are allowed to ignore it.

While these bizarre individual decisions have been made in a random fashion, there is a readily identifiable pathology underlying the entire mess. Unlike Apollo, Artemis is not a purpose-driven program. It is a vendor-driven program. Apollo spent money in order to do things. Artemis is doing things in order to spend money. This has led to an insane program design. Clearly, if we wish to get humans to Mars, we can’t have the program managed in the same way.

Many people who have been following the floundering of Artemis are acutely aware of its problems. For this reason, some have proposed a radical solution. Instead of putting NASA in charge they would simply hand the whole program over to SpaceX to design, build, and fly.

As seductive as it might sound, I do not believe this proposal is either practical or proper. While SpaceX is technically excellent, it is also self-interested. It would represent an enormous conflict of interest for Elon Musk to avail himself of presidential power to direct many billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money into his own company. This might work for a short time, but it would guarantee program cancellation as soon as political fortunes shift a bit to give Democrats control of either the House or the Senate. In order to survive and succeed, the Mars program must have broad support. This cannot happen if it is seen as the personal hobby horse or private piggy bank of an eccentric businessman who has now defined himself in extremely partisan terms.

As a somewhat superior alternative, one might launch the Mars program as a prize competition. For example, a $6 billion prize could be offered to the first company to land a 30-ton payload on Mars, with a further $6 billion awarded to the first outfit to land at least 4 people on Mars to explore there for at least a year and then return them to Earth. Second prizes of $4 billion for each milestone could be provided to the runner-up.

Such an approach could be quite economical, as the maximum cost to the taxpayer would be fixed in advance and no government money would be spent at all unless the missions really occurred and were successful.

There are problems with this approach, however. The government procurement system would have to be changed to allow billions of dollars to be appropriated but then set aside to be spent at an indefinite future date, with no change of mind on the part of the government allowed. Assuming that can be solved, still other difficulties remain. For starters, the only company that is currently situated both financially and technically to go after such a prize is SpaceX, so many might still regard it as self-dealing.

Moreover, there is more at stake in sending humans to the Red Planet than just Mars exploration per se. Human Mars exploration will accomplish great science — it will let us know the truth about the potential prevalence and diversity of life in the universe. But it isn’t just about science. It’s about America. It’s about who we are. Are we still a nation of pioneers, leaders of the free world, a people whose great deeds are celebrated not just in museums but in newspapers? The program needs to be our affirmative answer to that existential question. That means that we need to do it, not just watch it. It needs to be our program, not their program. Only in this way can it function to bring Americans and others who share our commitment to reason, science, freedom, creativity, and progress together in a celebration and demonstration of the power of our highest ideals in action.

The American people have one instrument for exploring Mars: our national space agency, NASA. Yet, as outlined above, its human spaceflight program is currently incapable of doing the job. If it is to lead America’s humans-to-Mars program, or even function as a significant partner in its leadership, it needs to be fixed.

NASA’s Artemis program design is incompetent because the program has no purpose. It may claim that it does, with some of its camp followers mouthing bumper sticker slogans about lunar exploration, development, or even the trillion-dollar cislunar economy. But it is clear that no such goals actually animate Artemis’s engineering or programmatic design. Artemis is not about any lunar science or settlement or any other objectives outside of itself. It is about giving NASA and its contractors something to do that can provide a rationalization for providing them with cash. Therefore, the more complex, duplicative, and slow-moving the program is, the better.

This type of entropy is not unique to NASA. It occurs in most organizations. For example, a trade union might be founded as part of a struggle for shorter hours and better pay. But after that is past and forgotten, its primary purpose becomes providing steady jobs for the union officials.

While some of NASA’s components had a prior history, the agency was forged in the fire of the Cold War for the purpose of helping to win that conflict by astonishing the world with what free people could do. Within that overall urgent strategic objective, the Apollo program took central stage. It thus proceeded with focus and energy. Human nature was no different in the 1960s than it is today. Then, as now, there were plenty of people both outside and inside NASA who observed a river of government money and were keen to obtain part of the flow. The Apollo program leadership was repeatedly confronted by managers, technologists, and contractors demanding critical roles for space station, nuclear rocket, or super booster projects with the constant refrain of “you can’t do your program until you do my program.” But Apollo needed to actually get to the Moon, and by 1970, no less. So, its leadership showed these people the door.

NASA today has engineers that are every bit as good as those who did Apollo, and they are armed with far better tools. But the organization as a whole is brain dead. It is a body without a spirit. If it is to be brought back to life it must be inspired, literally — it must have its spirit put back into it. The only way to do that is by giving it an animating purpose.

To save NASA, it must be given a purpose-driven mission, it must understand that mission, embrace that mission, and devote itself to that mission. The mission is not there to serve NASA. NASA exists to serve the mission. The mission must come first.

There are three reasons to send humans to Mars: for the science, for the challenge, and for the future.

The early Earth and the early Mars were twins. Both were warm, wet, rocky planets with atmospheres dominated by carbon dioxide. Earth evolved life. If the theory is correct that life emerges naturally from chemistry through a process of complexification that occurs whenever conditions are right, then life should have evolved on Mars too. We need to know if it did, and if so, what forms it took. We now know from observations made by the Kepler Space Telescope that, out of the stars that are like our Sun, an estimated one in five have roughly Earth-size planets orbiting in their habitable zones. This means there are perhaps as many as 80 billion such planets in our galaxy alone. If life evolves wherever there is a decent planet, it means life is everywhere. Furthermore, since the entire history of life on Earth is one of development into diverse forms, including those manifesting ever greater capacities for activity, intelligence, and accelerated evolution, if life is everywhere, intelligence is everywhere. If we find evidence of past or present life on Mars, it means we are not alone. This is something that thinking men and women have wondered about for thousands of years. It is worth risking life and treasure to find out.

Moreover, while there are forceful arguments that can be made why life must be based on complex hydrocarbon molecules and aqueous chemistry, there is no a priori reason why life must necessarily employ the same DNA–RNA information system utilized by all life on Earth. In trying to understand the phenomenon of life, biologists today are like untraveled people who, having encountered only the Latin alphabet in their homelands, think it is what alphabets are. But in fact, it is possible instead to achieve the same purpose using the Cyrillic or Arabic alphabets, or even Chinese characters, which not only look different, but operate according to an entirely different set of principles. What alphabet does life elsewhere use? The question is of more than academic importance. Biotechnology is going to be one of the main engineering sciences of the twenty-first century and many to follow. It is nanotech made real. A different bioinformation system could offer engineering possibilities as much greater in comparison to DNA–RNA as silicon computers are to ones based on vacuum tubes, electric relays, or mechanical Babbage machines.

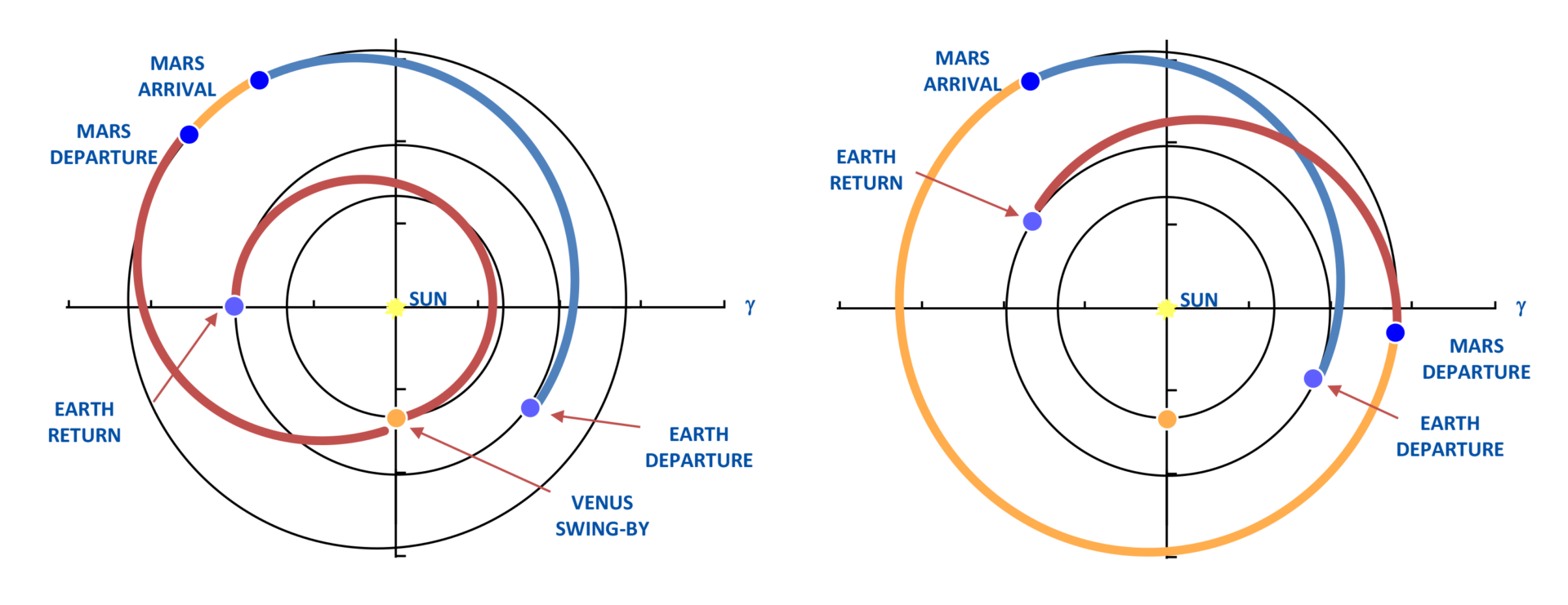

Fossil hunting to find evidence of past life on Mars will involve, as it does on Earth, hiking long distances through rough terrain, using intuition to search for subtle clues, doing heavy digging and pickaxe work, and performing delicate work to reveal traces of past life pasted between pages of hardened sediments now turned to rock. Finding current life will require wide-ranging field exploration followed by setting up drilling rigs to access liquid water a kilometer or more underground, bringing up samples, and analyzing them in a well-equipped lab on the Martian surface. These tasks are light years beyond the capabilities of robotic rovers. Only human explorers can achieve them. If we don’t go, we won’t know.

Nations, like individuals and institutions, grow when they challenge themselves and stagnate when they do not. A humans-to-Mars program would pay us back with massive generation of intellectual capital by inspiring millions of young citizens to develop their talents with a bracing challenge: Learn your science and you can be an explorer of new worlds! In the 1960s, the Apollo program issued precisely that challenge. What followed was a doubling in the number of our science and engineering graduates, whose innovations have since repaid us the program cost many times over. With the scientific professions now open to young women and minorities in a way that was simply not the case in the Sixties, the social impact of a bold Mars exploration program would be even greater today.

Forcing NASA to engage in a brave Mars program is precisely what is needed to transform the agency into an effective instrument for supporting all of the nation’s goals in space. NASA today is like a peacetime military with plenty of talented and enthusiastic junior officers but whose upper ranks have become filled by dead wood. It must be thrown into the heat of battle in order to purge it of its McClellans and find its Grants.

Finally, it is by rising to the challenge of Mars that we can demonstrate both the courage and the excellence that we need to show if we are to maintain world leadership. Americans were the first to fly to and the first to reach the Moon. The world needs to know that it is still true that Americans are the ones who can do — and who dare to do — what others can only dream of. So we need to be the first to Mars.

Philosophers who claim that we are living at the end of history could not be more wrong. We are living at the beginning of history. A thousand years from now there will be hundreds of new branches of human civilization thriving not only on Mars, but on scores of planets orbiting stars in this region of the galaxy. What language will they speak? What traditions and values will they hold dear?

Only people who choose to be parents get to have descendants. Only those nations that take part in the settlement of space will get to put their stamp upon the future.

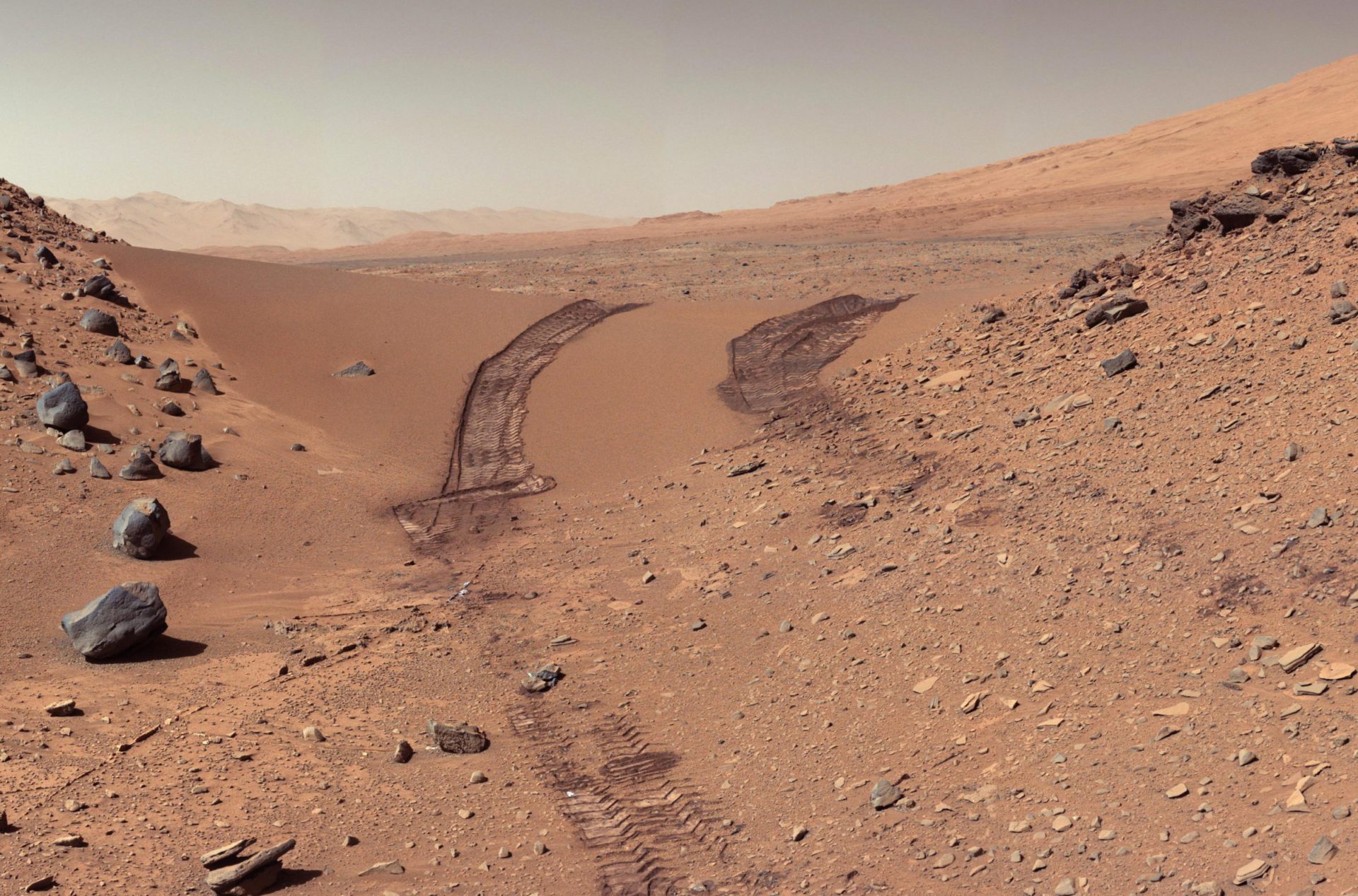

Of all the worlds beyond Earth currently within our reach, Mars is by far the most viable candidate for human settlement, as I’ve shown in detail in The New World on Mars: What We Can Create on the Red Planet (2024) and elsewhere. On the Moon, outside of a few ultracold craters at its South Pole, water exists only in concentrations of a few parts per million diffused in its soil. In contrast, Mars has oceans of water, including vast amounts in liquid form deep underground, continent-sized regions of frozen mud ranging from five to sixty percent water by weight, and massive formations of pure water ice glaciers, containing perhaps as much water as the American Great Lakes or more, extending from the North Pole down to 38 degrees N, the latitude of San Francisco on Earth. The Moon is lacking in any meaningful supply of carbon or nitrogen, elements essential for life. Mars, with an atmosphere that is 95 percent carbon dioxide and 2.6 percent nitrogen, has plenty of both. Mars not only possesses all the elements needed for industry but has had a complex geological history including both vulcanism and water action that has allowed many rocks to be concentrated into useful mineral ore. In contrast, the waterless Moon lacks many essential industrial elements and those that it has are all mixed together in trash rock. As thin as it is, averaged across the dome of the sky, Mars’s atmosphere provides the equivalent of about two feet (65 cm) of water’s worth of radiation shielding to its surface. That is well above the thickness required for a solar flare storm shelter, and thus fully adequate to protect both astronaut explorers and thin-walled greenhouses taking advantage of Mars’s 24-hour day to grow crops using natural sunlight. In contrast, the Moon has a month-long cycle of day and night and no atmosphere at all, making greenhouse agriculture on its surface a non-starter. Instead, plants would have to grow underground using electrically generated artificial light to support photosynthesis. The power requirement to do this at scale would be enormous. (For radiation concerns, see Endnote 1.)

For the coming age of space settlement, Mars compares to the Moon as North America compared to Greenland during the age of European maritime exploration. Greenland was closer to Europe, so Europeans reached it first. But it was too impoverished an environment to host more than a few outposts. In contrast, America was a place that could be not only settled but become the home for a huge vibrant new branch of Western civilization.

For our generation and those that will follow us in this century, Mars is the New World.

Mars can and should be settled. But it is important to be clear about how and why this should be done.

Elon Musk has propounded the idea that thousands of Starship flights should rapidly land a million people on Mars to create a metropolis that will “preserve the light of consciousness” after the human race is destroyed on Earth. This idea, which Musk says is inspired by Isaac Asimov’s noteworthy Foundation science fiction trilogy, is seriously misconceived.

In Asimov’s novels, a group of scientists are sent to settle the planet Terminus (also the name Musk has suggested for his colony) on the edge of the galaxy, so that after the anticipated collapse of the galactic empire their descendants can emerge to reconstruct civilization. It’s a grand read. But it is not applicable to the task at hand.

A human Mars civilization cannot be created in the manner of the D-Day landings, delivering settlers to land on the hostile shore 100,000 people at a time. The troops on Normandy beach could be supported from England by Liberty ships capable of carrying 10,000 tons of cargo each across the channel in a matter of hours. In contrast, Starships will be able to carry only about 100 tons of cargo from Earth to Mars and will take 6 to 8 months to perform the transit. Consequently, a Mars settlement of any size cannot be supported from Earth. Before large numbers of people go to the Red Planet, the agricultural and industrial base that are needed to feed, clothe, and house them will have to be developed, built, and up and running. The settlement of Mars must therefore occur organically, as the settlement of America did, with small groups of pioneers creating the first farms and industries that provide the basis for supporting ever larger waves of settlers to follow.

Furthermore, Martian civilization is very unlikely to emerge in the form of a million-person metropolis, as any city of that size requires a well-developed system of long-distance transportation to provide it with necessary materials. That is why million-person cities on Earth were rare until the invention of railroads. Instead, the initial settlement of Mars is most likely to occur in the form of a multitude of smaller towns, with locations optimized to access different types of material resources, and populations of thousands to tens of thousands, with perhaps 50,000 (the size of Renaissance Florence) representative of a cultural capital.

Regardless of how it is distributed, no Martian million-person civilization could possibly survive the collapse of human civilization on Earth. Technological civilization requires a vast division of labor. Given the multitude of the components and alloys in a good electric wristwatch, it is unlikely that a society of 1 million people could produce one, or even a wristwatch battery, let alone an iPhone.

So, the idea of sending people to Mars to survive the extermination of terrestrial humanity simply won’t work. Furthermore, it is so morally repulsive that its embrace would doom any program so foolish as to adopt it. Coated with ideological skunk essence, its protagonists would appear more like the selfish characters in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” dancing in a castle while everyone outside dies in an epidemic, than the heroes of Asimov’s Foundation series.

We are not going to Mars to desert humanity. We are going to Mars to strengthen humanity — to vastly expand its power to meet all future challenges by establishing new highly-inventive branches of civilization. We are not going to Mars to “preserve the light of consciousness” in an off-world hideaway. We are going to Mars to liberate human minds by opening an unlimited frontier to human hands. We are not going to Mars to party while the Earth burns. We are going to Mars to prevent Earth from burning by showing that there is no need to kill each other fighting over provinces when by invoking our higher natures we can create planets.

Together to Mars, then together with Mars, human freedom will expand into the cosmos.

We do not go to Mars to give NASA something to do, to plant a flag, or to set a new altitude record for the aviation almanac. We go to Mars for the science, for the challenge, and for the future. To achieve that purpose, we must implement a bold and effective program of field exploration. This understanding must be the basis of all aspects of mission design.

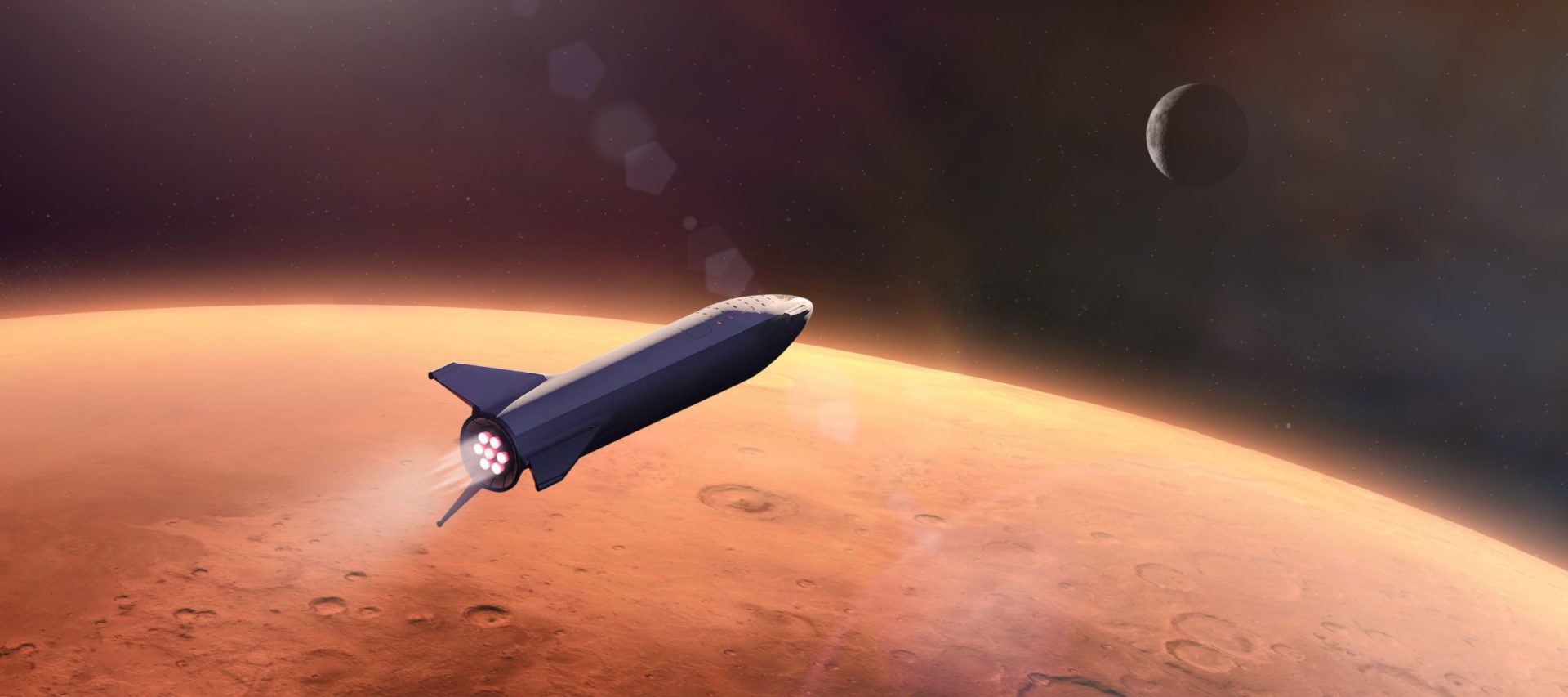

There are two radically different types of trajectories that can be used for a human mission to Mars. These, invoking terms used both in astrology and astronomy, are known as Conjunction-class and Opposition-class missions. Conjunction means that Mars is on one side of the Sun when Earth is on the other: viewed from Earth, the other two — the Sun and Mars — are in the same direction, hence conjunction. Opposition means that Mars and Earth are on the same side of the Sun: viewed from Earth, the Sun is in one direction and Mars in the other, hence opposition.

Conjunction missions involve a 2.5-year roundtrip to Mars, with roughly equal outbound and inbound legs of 6 to 8 months, and up to 1.5 years on the Martian surface. Opposition missions can be achieved somewhat more quickly, with a roundtrip time of 2 years, but almost all of that time would be spent in transit on two very unequal transfer legs and only about 30 days spent on or orbiting the Red Planet.

With the exception of occasional periods of time when some people who knew what they were doing had control of the ball, NASA managers have consistently embraced the Opposition class mission as the basis of their designs for getting humans to Mars. They have done this because their “figure of merit” for human Mars mission designs is minimum time away from Earth: the better mission design is the shorter one. Not to put too fine a point on the matter, this is really dumb. If your figure of merit for mission design is minimum time away from Earth, you should never leave.

Conjunction missions, in contrast, maximize astronauts’ time on Mars. They come with other important advantages as well. They require lower initial mission mass in low Earth orbit, because their propulsion requirements are less. They also involve lower radiation doses and fewer zero-gravity health effects because they spend less time in space and only travel in the region between Earth and Mars, while Opposition missions must fly long trajectories into the inner solar system passing as close to the Sun as Venus.

Ultimately, it all comes down to whether you actually want to be on Mars or not. If your assignment is to be able to claim you’ve been to Mars, every day on Mars is a burden. If your goal is exploration, every day on Mars is a treasure.

While there should be fair competition for all mission hardware used by the human Mars exploration program, it is a foregone conclusion at this time that the best launch system for the effort will be the SpaceX Starship. This soon-to-be operational system will offer comparable lift capacity to the SLS but with at least twenty times the launch rate and two orders of magnitude lower cost. We therefore assume that Starship will be selected as the program launch booster.

After payload delivery to low Earth orbit (LEO), however, there are a number of ways that the mission could proceed. SpaceX’s own proposed mission plan would be to fly the Starship to LEO along with 100 tons of cargo, and then refuel it with 600 tons of methane/oxygen bipropellant delivered to orbit by six tanker Starships. This would provide it with sufficient propellant to fly to Mars on a six-month Conjunction-class trajectory, aerobrake into Mars orbit, and then land on Mars. After unloading its cargo, the Starship could serve as the home for a very substantial crew for a year and a half, during which time it would be refueled with some 600 tons of methane/oxygen bipropellant produced from Martian carbon dioxide and water. This would be enough to fly back to Earth on a six-month trajectory carrying the crew and ten tons of cargo.

This mission plan offers a number of advantages. First and foremost, it requires use of only a single flight system that is already in an advanced stage of development and scheduled for use as part of the Artemis Moon program as well. Thus, the same team and infrastructure used to operate Artemis could support the Mars program simultaneously, offering both programs large cost savings. Second, the payload delivered to the surface of Mars is enormous relative to competing approaches, and so is the potential crew size. Elon Musk advertises Starship as a transport capable of delivering 100 colonists to Mars at a time. Such a large number would neither be necessary nor desirable for an exploration mission, but a crew of twenty or so might be readily accommodated. This would be around four times the size of the crew proposed in most other credible Mars mission plans. Moreover, the entire crew would be landed on Mars, where they all would be available to support the field exploration effort, and where they all could avail themselves of natural gravity and substantial radiation protection offered by the Martian environment. Unlike typical NASA mission designs, no one would be left on an orbiting mothership doing nothing useful except for minding the store, while undergoing extensive deconditioning from extended exposure to zero gravity and soaking up cosmic rays. Furthermore, there would be no mission-critical Mars orbit rendezvous on the return leg of the mission.

There are difficulties with this plan, however, which stem from the same source as the problem with SpaceX’s lunar mission architecture: the Starship is way too heavy to serve as an optimal ascent vehicle. By a rough estimate, to make the 600 metric tons of propellant required to refuel the Starship once on Mars within a year and a half would require a power source with an average round-the-clock output of 600 kilowatts. A solar array that could do that would cover 60,000 square meters — that’s over 13 football fields in size — and weigh about 240 metric tons. It would require three Starship flights just to deliver such a solar array to Mars, and it would then be a major burden to deploy and maintain. A more practical alternative would be to use nuclear power. We could imagine a plausible reactor design at this power level with a mass of about ten tons. (See Endnote 2.)

From a technical point of view, nuclear is the far superior alternative to supply the required surface power. However, to achieve the necessary compact size and weight, space nuclear reactors require the use of either plutonium or highly enriched uranium, which are both controlled substances. Thus the government will need to be involved. This poses issues, because the Department of Energy is afflicted by all the same bureaucratic pathologies as NASA, if not more so. A reactor development program done in-house at the modern DOE would never produce a working system on the timeline required for a human Mars mission program. Instead, it would have to be a commercially-led effort with the DOE playing a supporting role.

There is another way to mitigate the energy production problem. We could achieve a very large reduction in the amount of propellant needed by introducing an additional flight element, which I call a Starboat. This could be a vehicle of similar type to the current SpaceX Starship but scaled down by about a factor of five in mass. This could play numerous roles that would correct the weaknesses in the SpaceX plan. For example, it could do a direct return from the Mars surface to Earth using 120 tons of propellant or perform a low-Mars-orbit rendezvous using just 50 tons of propellant, with a single tanker in low Mars orbit being able to support five such return flights. It could also be lifted to Earth orbit fully fueled by a single Starship and sent directly to Mars with five tons of cargo without any Earth-orbit refueling, or 25 tons of cargo with a single tanker refueling. This would eliminate the problem of needing to launch seven Starships (the mission vehicle plus six tankers) within a single launch window as is required by the SpaceX plan. If, as assumed in these examples, the Starboat is used as the interplanetary flight vehicle, the crew size would have to be reduced from twenty to four or five, but that might well be appropriate for initial missions that will need to be conducted before all the base infrastructure is up and running.

Alternatively, instead of putting a tanker in low Mars orbit, a Starship fully fitted out for crew could be stationed there, and the Starboat only employed as a reusable shuttle between the surface and orbit. In that case, the plan could retain the ability to employ twenty-person crews, as they could ride out and land Mars along with 100 tons of freight on a standard Starship, only needing to accept the closer quarters on the smaller vehicle during a short Mars-to-orbit flight on the return leg.

The development of the Starboat would also fix the excessive launch problem with the SpaceX Artemis mission plan. The current plan requires 200 tons of propellant to be delivered to low lunar orbit to fuel the Starship on a roundtrip sortie to the lunar surface. At one fifth the size, a Starboat could make the same trip with only 40 tons of fuel. Similarly, the propellant requirement for a round trip from the Gateway to the lunar surface would be reduced from 400 tons to 80. And this could be further reduced by another factor of four when and if lunar oxygen production becomes operational. (See Endnote 3.)

The Starboat could also serve as the upper stage of a reusable first-stage booster in the same class as the Falcon-9, Neutron, and New Glenn boosters, thereby creating a fully reusable medium lift system capable of performing many important supporting mission roles. With a payload delivery capability to Mars of up to 25 tons, about twenty times as much as the landing system used to support the Curiosity and Perseverance missions, it could also deliver large scale robotic exploration missions to the Red Planet, as we shall discuss below.

Finally, and critically, the Starboat would endow the Mars base crew with global mobility. Mars is a planet with a surface area equal to all the continents of the Earth put together. It cannot be explored from a single base using slow moving ground vehicles with limited range. To explore Mars competently, we need worldwide access and the ability to travel rapidly across distances of continental scale. With 50, or better yet, 100 tons of propellant, the Starboat could give us this capability in spades. (See Endnote 4.)

Without Starboat, Mars base explorers would be limited to a region about the size of Brooklyn. With Starboat, they would have the freedom to roam over an expanse nearly double the size of the continental United States.

If additional Starships were landed to establish refueling bases scattered at long distances across the planet, more such explorable regions could be opened up. Nine such refueling stations would provide coverage of the entire world.

The Starboat would add enormously to both Artemis and Mars mission effectiveness, and make the two programs coherent with each other. It should therefore be developed as an essential program element. (See Endnote 5.)

The first requirement to get the humans-to-Mars effort started right is to create a competent program leadership. A Tiger Team needs to be established within NASA composed of technically excellent people who understand the purpose of the program and whose first loyalty is to the mission. The program cannot be led properly by people who are representing outside interests such as various technology development programs, aerospace companies, or NASA centers who are looking for a piece of the action. The program will undoubtedly need the services of many such entities, but they are vendors to the program, not the purpose of the program. You don’t run a company in order to deliver cash to vendors. You pay vendors in order to pursue the purposes of the company. If it is to succeed, the program must be purpose-driven, not vendor-driven.

The Tiger Team needs to be able to direct the resources of NASA to serve its purposes. These should include NASA’s Artemis program and its robotic Mars Exploration Program.

The Artemis program needs to be reconceived in a way that makes it both internally coherent and fully supportive of the development needed for the human Mars exploration effort. A clean mission architecture for this would employ Starship for Earth-to-orbit launch and refueling in both low Earth orbit and low lunar orbit, supporting roundtrip sorties from lunar orbit to the surface using Starboat, as an initial capability. Lunar oxygen production enhanced by surface nuclear power should then come onboard at the earliest possible date to provide a powerful force multiplier. Miscellaneous other elements associated with the current program, including the Gateway, SLS, the expendable hydrogen/oxygen National Team lander, and probably Orion are not necessary, and their very ample funds should be reallocated to things that are.

NASA’s robotic Mars Exploration Program is one of the jewels in the space agency’s crown. Since being restarted after a twenty-year post-Viking hiatus with the Mars Pathfinder and Mars Global Surveyor missions launched in 1996, it has had a great run, including five successful rovers, two stationary landers, four orbiters, and a helicopter, and only two mission failures. But recently the program has become bogged down with the design of an excessively costly and complex Mars Sample Return mission that has little relevance to either the search for life on Mars or preparation for human landings. It would be of much greater value to both the human exploration program and Mars science in general if instead of spending $10 billion on a Mars mission to return a small sample from a single site in about a decade, the Mars Exploration Program use those same funds to launch twenty missions with an average cost of $500 million each. These could deliver a varied cast of rovers, helicopters, and drillers, armed with all sorts of instruments and life detection experiments to numerous locations across the Red Planet, backed up by high data-rate orbiters equipped with ground-penetrating radar capable of identifying subsurface caverns, lava tubes, water, and other resources. Such a broad-ranging robotic survey would allow the Tiger Team to identify the best sites for human Mars bases and settlement.

Once a good candidate site for the first base is chosen, a Starboat or Starship should be landed there, delivering not one robot, but an entire robotic expedition. This would include many helicopters and rovers to characterize the site and its surroundings in as much detail as possible and emplace navigation beacons and radio repeaters throughout the region. The lander could also carry a well-instrumented lab to receive and analyze samples brought back to it by the mobile units. Construction rovers could also be used to set up the base power system and other facilities and to mine water. Manufacture of methane/oxygen propellant could then be initiated, refueling the lander for ascent.

With determination, focus, and a bit of luck, such a mission could conceivably be launched by 2028 — within President’s Trump’s four-year term — thereby giving the Mars effort a solid launch both technically and politically, as the scientific bonanza it would produce would be so enormous as to powerfully counter those skeptical of the program’s merit.

This done and other preparations made, in 2031 the first human mission could be sent to the base, where prepared facilities and a fully fueled ascent vehicle would await them. The crew could then proceed to explore the region at maximum effectiveness, working as a combined operation with a large team of robotic scouts. As this program unfolds at Mars Base 1, robotic survey efforts followed by robotic expeditions could proceed to continue to identify and develop additional sites planetwide for more bases.

The science return of such a program would be beyond reckoning. The future it would open would be limitless.

The linear no-threshold (LNT) methodology is a common and commonly misused approach to warning about radiation risks. It posits that a small radiation dose that has no immediate effects holds a proportional fraction of the same risk as a large dose that would be fatal. So, for example, using LNT methodology, if drinking 100 glasses of wine in one night would kill you, drinking one glass would pose a 1 percent risk of death. This is false.

Cosmic-ray dose rates on the International Space Station and on the Martian surface are about half those experienced in interplanetary space, because having a planet beneath you shields out half the sky. About a dozen astronauts and cosmonauts who are veterans of long-duration missions on the ISS or Mir have experienced cumulative cosmic ray doses equivalent to a roundtrip Mars mission. Even based on LNT methodology, one would calculate only about a 1 percent statistical risk of radiation-induced cancer for each of these individuals. In fact, no significant radiological health effects have been observed on members of this group.

A research program devoted to increasing the radiation dose rate among a larger group of human subjects for the purpose of generating cancer cases does not pass the ethical smell test. Any such proposed research program would unquestionably be rejected out of hand by the medical review board of any American hospital. This means that the data from past human missions to and beyond low Earth orbit remains the best data available, and it suggests that radiation effects of a Mars mission would be manageable.

Solar: If we wish to make 600 metric tons of methane/oxygen propellant over a 500-day period, we would need a source capable of generating an average power of 600 kilowatts around the clock. The solar flux reaching the Martian surface at low latitudes under completely clear conditions at high noon is about 400 W/m2, but averaged over the course of a 24.6-hour Martian day (or “sol”) is only 100 W/m2. If we take into account loss of sunlight due to atmospheric dust and wish to have a bit of margin, it would be wise to estimate this to average about 50 W/m2 over the course of 500 days. Converting this to electricity using photovoltaics at an efficiency of 20 percent would therefore yield an average power of 10 W of electric capacity (We) per square meter. A solar array capable of producing 600 kWe would therefore need to have an area of 60,000 square meters — roughly 13.4 football fields in size. This would require frequent cleaning to maintain its power level, and at an estimated mass of 4 kg/m2 would weigh about 240 metric tons. It would thus require three Starship flights to deliver such a solar array to Mars, and be a major burden to deploy and maintain it as well.

Nuclear: The Soviet Topaz nuclear reactor had an electric power output of up to 10 kilowatts and had a mass of 1 metric ton. This is about the high end of the performance targeted by NASA’s Kilopower project that began in 2015. However, in the 1980s, NASA and the Department of Energy had a joint project known as SP-100 to develop a 100 kWe space nuclear reactor, which was taken to a fairly detailed level of design. SP-100 had a projected mass of 4 tons, so the necessary power to produce 600 tons of propellant could be provided by six such reactors with a total mass of 24 tons — one tenth of that needed by the photovoltaic system. Alternatively, a new design could be developed for a 600 kWe reactor, which would probably have a mass of around 10 tons, since the mass of nuclear reactor systems tends to scale up roughly in proportion to the square root of their power.

Oxygen can be produced on the Moon by breaking down lunar rocks, which are all oxides of metals. For example, you can react hydrogen with iron oxide at 800 degrees C to produce metallic iron plus water. The water product can then be electrolyzed to produce oxygen, as well as hydrogen, which can then be recycled to reduce more iron oxide. Oxygen can also be produced by electrolyzing lunar ice, but that is only available in ultracold, permanently shadowed craters near the Moon’s South Pole.

Producing propellant on Mars is much easier, as water is widely available and the hydrogen produced by electrolysis can be catalytically reacted with the carbon dioxide that comprises 95 percent of the Martian atmosphere to produce methane and water, with nearly 100 percent selectivity and yield. In addition, carbon dioxide can be split directly into carbon monoxide and oxygen in chemical reactors, or used together with water to produce both oxygen and food via photosynthesis. Methane/oxygen bipropellant is 78 percent oxygen by weight, and producing such oxygen on the scale needed by the Starboat would be a far more tractable task than that required to service the full-scale Starship.

Starboat can reach low Mars orbit using 50 tons of propellant. That means that using 50 tons or less, it could launch from anywhere on Mars to land anywhere else in less than an hour. That’s one way. But it could also go out and back 1,000 km using 50 tons of propellant, or 2,200 km using 100 tons. Thus, employing a Starboat as a sortie vehicle, a single base could support the exploration of a region 4,400 km in diameter, enclosing some 16 million square kilometers of land.

Traveling from the Martian surface to Mars orbit requires a rocket-propelled velocity change (known as delta-V) of 3.8 km/s. However, it would only need a delta-V of about 0.3 km/s to come down and land — because it can slow down using Mars’s atmosphere — for a total roundtrip delta-V of 4.1 km/s. This is nearly the same as the 3.8 km/s delta-V needed to travel roundtrip from low lunar orbit to the lunar surface.

Thus a Starboat designed for use as an orbit-to-surface ferry on Mars could readily serve the same function on the Moon. It is true that mission performance could be potentially optimized further by creating specialized Starboat designs for each of its potential roles. For example, a Starboat used only for lunar landing and ascent could be built lighter as it would not need thermal protection, while the range of one used for surface-to-surface travel on Mars could be extended by adding wings. But creating more types of specialized flight vehicles would add to the program’s development cost. The question then becomes where across a spectrum ranging from generalization to specialization the program should place its bets.

Elon Musk has argued for a one-size fits all Starship-only mission architecture. This offers maximum simplicity but imposes great costs. By going to a two-size fits all Starship-and-Starboat plan to implement both Mars and lunar missions, 80 percent of these costs can be eliminated. But some might go farther, recommending three, four, or five types of vehicles. Eventually, we probably will get them all. But I think having two types is the right place to start. It’s a judgment call.

Keep reading our Spring 2025 issue

How gain-of-function lost • Will AI be alive? • How water works • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?