This essay is accompanied by the New Atlantis critical edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “Rappaccini’s Daughter.”

There are those whose noses wrinkle whenever they catch a whiff of allegory in the air. Edgar Allan Poe, in his 1847 review “Tale Writing — Nathaniel Hawthorne,” quips that the best success a writer of allegory can hope for is to accomplish a feat that is not worth doing in the first place. “There is scarcely one respectable word to be said” in its defense. Allegory is obtrusively didactic, Poe elaborates, and thus it disturbs the equilibrium, essential to well-made fiction, between the narrative surface and the thematic depths: meaning should be an undercurrent of subtle force, and allegory redirects it to the surface, where it overwhelms the life-giving illusion of the story.

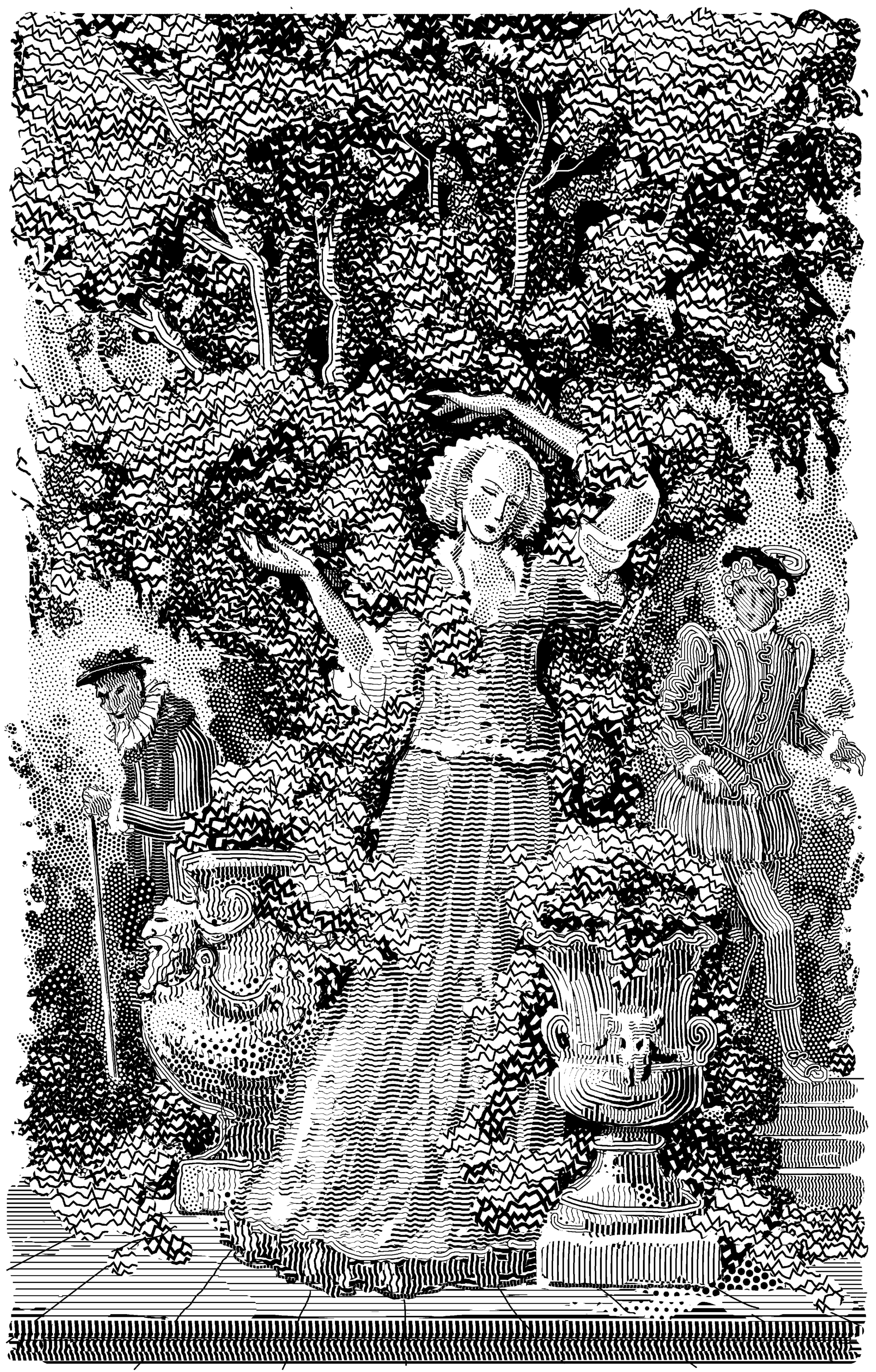

One suspects that, though Poe does not indict the story specifically, he has “Rappaccini’s Daughter” very much in mind as he lights into Hawthorne’s use of allegory. “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” published in 1844, is the tale of a beautiful maiden confined to her father’s house and garden in long-ago Italy, and of the handsome young man who espies her from his window, falls prey to her enchantment, and with only the best intentions brings about her death. The garden is explicitly likened to Eden, though a malign fallen version thereof; the maiden’s father is an eminent doctor, explicitly likened to Adam, who has cultivated plants of unexampled deadliness to be used for medicinal purposes, and to fortify his daughter against the world’s various cruelties. The story has a texture of heightened allusiveness that bristles with meaning, inviting the reader with sensitive feelers to reconsider the wisdom not only of Genesis but of Dante, Milton, Ovid, Spenser, Machiavelli, and the modern scientific project. Hawthorne takes on erotic mysteries, scientific aspirations, venerable religious wisdom — and he composes about as richly literary a short story as any American writer has ever produced.

It is fortunate that, in this as in other matters, we need not take all our cues from Poe. But with a playful nod, Hawthorne even mocks himself for the semblance of pretentiousness. In a meta-fictional preface — rendered in the third person — he attributes this and others of his stories to a fantastical author by the name of Monsieur de l’Aubépine (French for the hawthorn tree). His writings show “an inveterate love of allegory, which is apt to invest his plots and characters with the aspect of scenery and people in the clouds, and to steal away the human warmth out of his conceptions.” But there is hope for poor M. de l’Aubépine and his befuddled readers, for “occasionally a breath of Nature, a raindrop of pathos and tenderness, or a gleam of humor will find its way into the midst of his fantastic imagery, and make us feel as if, after all, we were yet within the limits of our native earth.”

And where but within the limits of our native earth should we expect to find ourselves in the story of its origin, the central allegory of the Western canon? Better yet, in Hawthorne’s inversion of that story we find the origin of the modern world, the fallen world, with all of our attempts to compensate for long-lost grace twisted together in a serpentine tangle. There is the agenda for power, the only important factor in a world bereft of moral content; there is the scientific project to control hostile creation, even re-create it better; there is the promise of redemptive love. There is much confusion in this return to an inverted paradise, the “Eden of the present world,” with its life-giving poison and purity incarnated in evil, but as Dante’s Beatrice guides him into the infinite unknown, so Hawthorne draws us in.

The time is “very long ago.” Giovanni Guasconti has come from Naples to Padua to study at the university. His very name spells erotic misfortune twice over: Don Giovanni was the lover of demonic appetite immortalized in Mozart’s opera and dragged to hell at the end, and guastare means to spoil or to ruin. Perhaps Hawthorne’s young man, like his notorious namesake, will be ruined as well as do the ruining. Giovanni rents an apartment in a gloomy mansion that once belonged to a noble local family: “The young stranger, who was not unstudied in the great poem of his country, recollected that one of the ancestors of this family, and perhaps an occupant of this very mansion, had been pictured by Dante as a partaker of the immortal agonies of his Inferno.” The Dantean motif is struck early, and the question will arise whether the earthly paradise where Giovanni will soon find himself is not in fact hellish.

Giovanni learns presently that his window overlooks the strange and beautiful garden of Doctor Rappaccini, whose name bespeaks a rapacious nature. Giovanni supposes the garden has a long and distinguished history: its centerpiece is a marble fountain in ruins, clearly superb once, but now so hopelessly fragmented that its original design cannot be discerned. Water continues to flow there, however; nature is impervious to the wreckage of human art, and the water seems to Giovanni “an immortal spirit, that sung its song unceasingly and without heeding the vicissitudes around it, while one century imbodied it in marble and another scattered the perishable garniture on the soil.” A glorious shrub in a marble vase stands in the middle of the pool, its purple blossoms gem-like and entrancing. Plants abound, all bearing in their luxuriance the signs of painstaking human tending, their every particularity appreciated by “the scientific mind that fostered them.”

The scientist himself presently appears, austere, sickly, getting on in years, flagrantly intelligent in aspect, but obviously never in his life warm-hearted. His perusal of the plants is preternaturally acute, “as if he was looking into their inmost nature”; he takes in every last detail, understands at a professorial glance the morphological intricacies and indeed the very “creative essence” of each one of his charges, his creatures. Yet despite this evident intellectual mastery, “there was no approach to intimacy between himself and these vegetable existences.” He walks among his plants with a caution verging on dread, never touching a leaf or stem, never leaning close to inhale a fragrance. It is as though “malignant influences” were ever poised to inflict “some terrible fatality” if the doctor made a wrong move. That Rappaccini should demonstrate such trepidation in what ought to be the “most simple and innocent of human toils” unnerves Giovanni. Fear incites his imagination. “Was this garden, then, the Eden of the present world? And this man, with such a perception of harm in what his own hands caused to grow, — was he the Adam?” The armature of the allegory seems clearly defined; yet will things be as simple as Giovanni’s first thoughts suggest?

Rappaccini’s garden pointedly recalls the original Eden and just as pointedly repudiates it. In Paradise Lost, John Milton hymns the artless magnificence of the Garden, fed by the waters of a fountain perpetually flowing:

How from that Saphire Fount the crisped Brooks,

Rowling on Orient Pearl and sands of Gold,

With mazie error under pendant shades

Ran nectar, visiting each plant, and fed

Flowrs worthy of Paradise which not nice Art

In Beds and curious Knots, but Nature boon

Powrd forth profuse on Hill and Dale and Plain.

This is plainly God’s handiwork, not man’s. Rappaccini’s garden, on the other hand, is the fruit of human intelligence applied to inhuman Creation. There man has arrogated to himself a share in godly power. He alters the products of nature to serve human ends — in this case, the foremost end of modern science, to cure disease (or so the reader thinks, at this point in the story); and thus he grows living things that have something manufactured, unnatural, about them.

If Rappaccini resembles Adam, it is not in his innocence but in godlike knowledge, acquired only after the Fall. In Genesis the serpent promises Eve that if she and Adam eat the fruit of the forbidden tree they will become “as gods, knowing good and evil.” When the deed was done, “the Lord God said, Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil”; and to prevent their eating from the Tree of Life and gaining immortality, God expels the couple from the Garden. Rappaccini embodies the fearfulness with which man has walked the earth ever since; death threatens at every turn. Man has a tough row to hoe in the Eden of the fallen world. To advance the cause of human freedom from affliction, Rappaccini has risked his own health, and faces mortal danger every day as he goes about his work.

He has also raised a daughter of apparently invincible vigor, at least in the cloistered world she never leaves. Even though he is wearing heavy gloves and a mask, Rappaccini balks at pruning the show-stopping shrub at the garden’s center, bedecked with purple blossoms like gems but somehow menacing in its beauty, and he calls the daughter, Beatrice, to take charge of this wondrous but terrible plant. Unlike her father, Beatrice traipses fearlessly about the garden, stopping to smell the flowers, and she addresses “the magnificent plant” as her sister; the plant’s perfume shall be “the breath of life” to her. In Giovanni’s perception the girl and the plant are conjoined in their beauty, rarity, and strangeness; he dreams of them that night, and the dream’s enchantment warns him of “some strange peril in either shape.” But next morning cool rationality dispels the sense of mystery, with its sinister undertow.

That day Giovanni presents a letter of introduction to the physician and professor Signor Pietro Baglioni, an old friend of his father’s. (Bagliore means a flash or dazzling light; un bagliore di speranza, a ray of hope.) Giovanni asks him about Rappaccini, thinking the two doctors and men of science must be on cordial terms. However, while Baglioni acknowledges Rappaccini’s expertise, he warns Giovanni against this obsessive character who “cares infinitely more for science than for mankind,” and “who might hereafter chance to hold your life and death in his hands.” One may be reminded at this point that in The Prince, Machiavelli teaches, in his subtlest sidelong fashion, that the man who wields the power of life and death over others is godlike. This instruction lies at the heart of modernity’s founding, overturning the classical wisdom, most explicit in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, that it is the man devoted to the contemplation of eternal things — the heavenly bodies, the truths of mathematics — who can be called divine. The Bible, for its part, admonishes men that even to think of becoming like God is self-destructive folly. “Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,” the Hebrew Bible instructs; in the New Testament, Jesus teaches us that to enter the kingdom of Heaven we must become as little children, innocent and unimpeded by the world’s supposed wisdom. Rappaccini’s is a decidedly modern intelligence, craving power over nature, and indeed over the lives of men and women. He has even concocted poisons, Baglioni goes on, that Nature itself would never have exuded without his prodding. Rappaccini has not used these for evil purposes, but his probing and relentless mind has uncovered their potential for evil. And Beatrice is said to possess her father’s learning.

When Giovanni next sees Beatrice from his window, her vivid beauty, even more remarkable than he remembered, startles him, as does her “expression of simplicity and sweetness,” qualities he had not suspected at first viewing. But then she plucks a jeweled purple blossom from the magnificent plant to wear on her bosom, and a drop of moisture from the flower stem falls on the head of a lizard at her feet. The unfortunate little creature immediately claws the air and bites the dust. Beatrice crosses herself but goes on as though nothing has happened; “the fatal flower” she pins to her dress. The spectacle flummoxes Giovanni. “What is this being? Beautiful shall I call her, or inexpressibly terrible?”

To Giovanni, Beatrice’s shining innocence, simple and sweet, appears at odds with her virtually demonic frightfulness. Once again Machiavelli may clarify the matter, or complicate it. Machiavelli is out to establish the innocence of terrible things: all the deceit, treachery, and violence that men perpetrate in the pursuit of their desires are nothing to be repented of. Men ought not be faulted for “the natural and ordinary desire to acquire” — to win themselves wealth, renown, sexual pleasure, and above all the power over life and death. In the Machiavellian world original sin has been expunged. Human beings needn’t even trouble to accept God’s grace in order to enjoy redemption from their fallen nature; there never was a Fall to be redeemed from. Great men, the ones who gain supreme mastery over others, are necessarily terrible yet morally unexceptionable in a world where traditional morality has ceased to be a drag on human need.

In a chapter of The Prince entitled “Of Cruelty and Mercy, and Whether It Is Better to Be Loved Than Feared, or the Contrary,” Machiavelli extols the Carthaginian general Hannibal’s success in forestalling dissension among his soldiers. “This could not have arisen from anything other than his inhuman cruelty which, together with his infinite virtues, always made him venerable and terrible in the sight of his soldiers; and without it, his other virtues would not have sufficed to bring about this effect.” The import of this cunning formulation of Machiavelli’s flicks in and out of sight like a serpent’s forked tongue. One moment, being terrible is distinguished from virtue; the next, it is an indispensable virtue. Welcome to modern thought, modern times.

Despite this erasure of traditional morality and with it the liberation from divine oppression, Rappaccini still labors under the shadow of Genesis, feeling in his ravaged body the aftermath of the Fall: his modern scientific intelligence cannot absolve him of the ancient stain. Rappaccini’s frail body houses a vibrant mind, and he surely wishes he could be all mind, the pain of its wearisome shell forgotten. But the pain and debility are there to remind him that for all his power he is not his own creator. He cannot quite break free of the hold of the Biblical truths, however he might labor to do so; he lives betwixt and between, though doing his utmost to bring modernity to full flower.

Beatrice, on the other hand, looks to be modern after the Machiavellian manner; through Giovanni’s eyes, Hawthorne presents her as terrible yet innocent. Machiavelli would likely say terrible and innocent, for yet suggests a moral incongruity that he is working to erase. What Giovanni sees of the beautiful young woman’s nature appalls but allures him. Beatrice appears more sinister even than her father, for she represents a generational advance in the tolerance of evil: she is inured to the terrible element in which she works, as he is not. If he is the Adam godlike in knowledge yet all too human in his suffering, she is effectively a goddess utterly at home in the toxic Eden of her father’s making. Moreover, she is as much the child of his disembodied scientific mind as his physical offspring; as the late professor Edward Rosenberry has observed, “to the man of learning, ‘the next generation’ can only be those he teaches, the children of his intellect, the inheritors and habitual possessors of objects and ideas which he has, often fearfully, brought into being. It is an old but vital story that Hawthorne is telling here: how the adventure of one age is the custom of the next, and how long familiarity can make a safe and stable haven of the very brink of disaster.”

When Giovanni tosses a bouquet of “pure and healthful flowers” down to Beatrice, she responds prettily that she would to like to reciprocate with her gorgeous purple flower, but it would never carry up to his window. As she heads home, Giovanni believes he can see his gift of flowers withering in her hands. For days afterward, he stays away from the window, fearful of some dire moral infection. Infection takes root all the same. He lacks “a deep heart,” or at any rate his heart is not moved deeply now, but his “quick fancy” and southern ardor stoke his erotic fires. “Whether or no Beatrice possessed those terrible attributes, that fatal breath, the affinity with those so beautiful and deadly flowers which were indicated by what Giovanni had witnessed, she had at least instilled a fierce and subtle poison into his system.” He does not love her, although her beauty transfixes him; she does not horrify him, though he questions whether her spirit is as deadly as her person. Yet something of both love and horror enters into him, and their tumultuous conflict is a plague. “Blessed are all simple emotions, be they dark or bright! It is the lurid intermixture of the two that produces the illuminating blaze of the infernal regions.” The bastard cousin to love that Beatrice inspires in him is a hellish torment.

One day Signor Baglioni buttonholes him in the street, and as they are talking, Rappaccini walks past, eyeing Giovanni intently, “as if taking merely a speculative, not a human, interest in the young man.” Baglioni heatedly warns Giovanni that Rappaccini must know who the youth is, and that he is surely carrying out one of his fiendish experiments on Giovanni, as coldly as he would on the small animals he kills to test the potency of his venomous plants. When Baglioni asks Giovanni what part Beatrice plays in this mystery, the youth bolts in a huff. Baglioni vows to employ “the arcana of medical science” to save his old friend’s son from the clutches of Rappaccini and his daughter.

Giovanni, for his part, plunges ever more deeply into passion for Beatrice, not caring “whether she were angel or demon.” Yet as the housekeeper of his lodging-house leads him to a private entrance into Rappaccini’s garden, he wonders whether that passion is not mental rather than heartfelt. Giovanni appears to be conducting an experiment of his own, with Beatrice as its subject. He has been dreaming of meeting Beatrice face to face, and of “snatching from her full gaze the mystery which he deemed the riddle of his own existence.” He is not simply after erotic fulfillment in any of the usual ways, whether blatantly carnal or sublimely spiritual: he is in hot pursuit of an answer. Hawthorne delicately indicates that Giovanni has in common with Rappaccini this engine persistently whirring in his skull. It is left to the reader to contrast the fiery yearning of eros with the cool but equally potent impulse of scientific inquiry, both potentially reaching out toward the infinite, both in this case pointed toward the same end.

Once in the garden, Giovanni studies the scene with a dispassionate critical eye:

The aspect of one and all of [the plants] dissatisfied him; their gorgeousness seemed fierce, passionate, and even unnatural…. Several also would have shocked a delicate instinct by an appearance of artificialness indicating that there had been such commixture, and as it were, adultery of various vegetable species, that the production was no longer of God’s making, but the monstrous offspring of man’s depraved fancy, glowing with only an evil mockery of beauty.

The condemnation of Rappaccini’s experiment comes hard and fast: moral deception, mental perversity, grotesquerie, ungodliness thrive here.

Then Beatrice, self-proclaimed sister to the flowers, enters. Surprised but pleased to find Giovanni in the garden, she flatters him as a floral connoisseur, and says that if her father were there he would regale him with all manner of botanical lore. When Giovanni replies that he has heard she is a match for her father in knowledge, she laughingly denies any such learning on her part: all she knows is colors and smells, and some of those she finds repellent. Don’t believe the rumors about her, she tells him: believe only what you see with your own eyes. Recalling the distressing things he has seen, Giovanni tries to put them out of mind, and declares he will believe only what she says. Beatrice avers that whatever she says is true. Unnerving fragrances, with their hint of menace, intrude upon his enchantment, but only for an instant. “A faintness passed like a shadow over Giovanni and flitted away; he seemed to gaze through the beautiful girl’s eyes into her transparent soul, and felt no more doubt or fear.”

Giovanni believes his eyes, though only when their evidence heartens him, while he discounts what he would prefer not to have witnessed. And in any case can eyes really see into souls, if there are indeed souls to be seen? As Machiavelli explains, what you see can readily deceive you: “Men in general judge more by their eyes than by their hands, because seeing is given to everyone, touching to few. Everyone sees how you appear, few touch what you are.” Giovanni will presently know Beatrice by touch. As he reaches to pluck a purple blossom from the magnificent plant as a memento, Beatrice cries out that the plant is fatal, and grabs his hand to stop him. The next morning the livid imprint of her fingers is seared into his flesh. This touch of hers is devastating to the soulful illusion that beguiled his eyes.

Yet lovelorn illusion dies hard; Giovanni rushes to Beatrice’s side again and again. When he is slow to appear, Beatrice calls to him from below his window, sending up “the rich sweetness of her tones to float around him in his chamber and echo and reverberate throughout his heart: ‘Giovanni! Giovanni! Why tarriest thou? Come down!’ And down he hastened into that Eden of poisonous flowers.” She becomes the wooer, in Hawthorne’s inversion of Don Giovanni’s serenade, Deh vieni alla finestra (Come to the window); and Guasconti speeds to be with her, in the death-haunted Paradise.

Together, however, they keep their distance from one another, quite literally. Their eyes and their speech are flush with love, but except for this perplexing moment, they never actually touch each other: “and yet there had been no seal of lips, no clasp of hands, nor any slightest caress such as love claims and hallows. He had never touched one of the gleaming ringlets of her hair; her garment — so marked was the physical barrier between them — had never been waved against him by a breeze.” Touch, of course, would certify the evil in her nature, and perhaps cause him irreparable harm. His longing fights against his fear, but she is adamant in her noli me tangere attitude. When he tries to run the blockade, she grows severe, and the suspicions about her monstrosity that he had suppressed again blacken his mind. But then her sunniness returns and her innocence wins him over, convincing him that his “spirit” knows her “with a certainty beyond all other knowledge.”

Signor Baglioni, who drops in unannounced and unwelcome one morning, informs Giovanni that his spirit is misleading him. Baglioni tells him the story, from “an old classic author,” about the beautiful woman whom an Indian prince sent as a gift to Alexander the Great. Her beauty enraptured the young conqueror; her breath, “richer than a garden of Persian roses,” especially allured him. A shrewd physician, however, warned Alexander to stay away: the beauty had been nourished with poisons from her birth, so that “she herself had become the deadliest poison in existence.” The prince’s murderous cunning, Baglioni goes on, has found its evil match in Rappaccini’s heartless scientific audacity: Beatrice too is envenomed, and her father intends Giovanni as a lab rat. “Perhaps the result is to be death; perhaps a fate more awful still.” To save Giovanni and Beatrice, Baglioni gives the youth a silver vial, wrought by the celebrated sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, that contains the antidote to Rappaccini’s poison.

Giovanni needs further proof of Beatrice’s malignity, so he buys a bouquet of flowers for her: should they wilt at her touch, he will be sure of her true nature. But as he is admiring his unexampled vitality and handsomeness in the mirror, he notices that the flowers are withering in his own hand. To confirm his fear, he breathes upon a spider in his room: the poison from within him kills “this deadly insect” on the spot. At this moment Beatrice’s alluring voice calls from the garden. Giovanni realizes then that Beatrice is the sole living being that his breath would not kill; enraged, he wishes that it could. He joins her in the garden, and her presence reminds him poignantly of her “delicate and benign power” that had “so often enveloped him in a religious calm.” But he cannot muster the “high faith” that would assure him Beatrice is in fact “a heavenly angel.” She feels, “with a quick spiritual sense,” the abyss opening between them, and they pitch into it presently, as they approach the shrub with the gem-like blossoms. The plant’s fragrance exhilarates Giovanni, and makes him fear his exhilaration. He asks Beatrice where the plant came from, and she tells him her father “created” it. Giovanni is incredulous: that a human being should create life is beyond him, and he presses for an explanation. “‘He is a man fearfully acquainted with the secrets of Nature,’ replied Beatrice; ‘and, at the hour when I first drew breath, this plant sprang from the soil, the offspring of his science, his intellect, while I was but his earthly child.’” As Beatrice grew up, the plant “nourished [her] with its breath.” That intimacy condemned her to “an awful doom”: there was no place for her in the world of men and women, and only when Giovanni appeared did she realize how lonely she had been.

Giovanni detonates: to ease her lonesomeness she has rendered him foul and corrupt, unfit for any companionship but hers. Beatrice’s heart breaks at his furious outburst. She professes not to know what he means: she is indeed a “horrible thing,” but surely he is untainted, and can return to the world outside as though he had never met her. To prove otherwise, he blasts an insect squadron out of the air with his breath. Appalled, Beatrice shrieks that it is her father’s science that has undone Giovanni, not her love, which she hoped to enjoy only for a brief season, and which would never have moved her to such enormity. “For, Giovanni, believe it, though my body be nourished with poison, my spirit is God’s creature, and craves love as its daily food. But my father, — he has united us in this fearful sympathy.”

There is a deft interplay throughout with the etymological link between spirit and breath, the Latin spiritus originally meaning “a breathing”: does Giovanni’s spirit make intimate contact with Beatrice’s own pure spirit, or is her toxic breath her genuine spiritual essence? Spirit is animo, while soul is anima; the two English words can be virtually synonymous, yet the Italian words lie miles apart in meaning, however close in sound. Animo also means mind, and Beatrice’s spirit, which she claims to be from God, is at least as much the product of her father’s mind. Beatrice’s sweet breath, her spirit distilled, is poison, the emanation not of nature but of scientific intelligence bent on power.

What is Giovanni to believe? The “utter solitude” that the two feel in being together now is not desolation pure and simple: from their shared isolation, Giovanni hopes, deeper closeness might spring. He also nurses the more extravagant “hope of his returning within the limits of ordinary nature, and leading Beatrice, the redeemed Beatrice, by the hand.” But what exactly would he be redeeming her from, if she is indeed innocent as she claims?

Beatrice is innocent according to the Machiavellian estimation, which celebrates the terrible victorious. Giovanni, who knows Beatrice as both innocent and terrible, would find this claim morally repulsive; the two qualities seem irreconcilable. Giovanni has seen and heard and touched Beatrice, and what he has touched belies what he has seen and heard. He has breathed in her essence, her spirit, which has altered his own, and the alteration has filled him with loathing. Leveled by his eruption of hatred, Beatrice has excoriated herself as a thing of horror; but earlier she was happy as the mistress of the poisonous garden, even ecstatic in her sisterhood with the magnificent plant; she seemed to accept her venomousness as any healthy creature accepts its nature.

Yet Beatrice is also innocent in the eyes of a God Who honors love and purity of heart, and Who holds out the possibility that one might be condemned in body yet redeemed in soul. Is this a world in which the Machiavellian “effectual truth” is not only sovereign but actually true, or does a loving God oversee His Creation, rewarding good, punishing evil, and offering salvation? Is the Machiavellian exoneration of “the natural and ordinary” in human desire a formula for the cultivation of unnatural men and women, the beguiling artifice of modern thought breeding monstrous deformities?

Even Beatrice’s name, redolent of happiness and blessedness, represents her dual nature. Her darker namesake is the hapless Beatrice Cenci, a sixteenth-century Italian noble raped by her father and executed for his murder. Her story, immortalized by Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1820 tragedy The Cenci and Guido Reni’s portrait, among others, intently interested Hawthorne. He would later observe in his Notebooks, after viewing the portrait in person for the first time,

I looked close into its eyes, with a determination to see all that there was in them, and could see nothing that might not have been in any young girl’s eyes; and yet, a moment afterwards, there was the expression — seen aside, and vanishing in a moment — of a being unhumanized by some terrible fate, and gazing at me out of a remote and inaccessible region, where she was frightened to be alone, but where no sympathy could reach her.

The parallels to Beatrice Rappaccini — a young woman violated by her father, innocent but defiled to the point of being cast out from humanity — are not difficult to draw.

The other Beatrice, of course, is Dante’s beloved, whom he first saw when they were eight years old, pined for throughout childhood and adolescence, then virtually worshipped as a saint after her death at the age of nineteen. La vita nuova (The New Life) recounts this passion in prose narrative and heart-wrung poetry. But it is in La Commedia (The Divine Comedy) that Dante’s love attains its celestial apex, and is reciprocated with purity and holiness perfected. Looking down from heaven, the sainted Beatrice saw that after her death Dante had fallen into “a way not true”; only by showing him the fate of the damned could she hope to save him, and she arranged for him to journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. She is waiting for him in the earthly paradise, the uppermost level of Purgatory, and there she chastises him for having been unfaithful to her memory and having engaged in vain and worthless loves; he feels “the venom of the argument” and learns to hate his sinfulness.

Beatrice guides Dante through Paradise — the heavenly paradise, far excelling the earthly one — and brings him toward the intellectual apprehension of the universe’s perfect order, which is to say, toward the ultimate love. Dante comes to realize that Beatrice is first and foremost God’s beloved, and later to understand that his own love for Beatrice is the lesser love, as love of God consumes him; when he forgets her in his overwhelming ecstasy, Beatrice approves. For Dante, love between human souls is not an end in itself but a means to the highest — the highest knowledge, happiness, sanctity, and love, all of which are united in the experience of Paradise. For Hawthorne’s young lovers in their blighted Eden, love would have meant passion so consumingly exclusive that it shut out the rest of the world.

Like Hawthorne’s Beatrice, Dante’s has the power to destroy: if she were to smile, she tells Dante, he would be burnt to ash by the sheer dazzle, like Semele when Jove revealed himself to her in his full glory. But the terribilità of Dante’s Beatrice is the force of love so intense that mortal powers cannot endure it, although it suits the blessed perfectly; the deadliness of Hawthorne’s Beatrice, on the other hand, is the product of demonic science conceived in hatred, fear, and ambition, and it makes normal human love impossible. These are two opposing versions of what godly power means, embodied in the energy of the erotic: the first enhances all existence, despite its latent frightfulness; the second bends to the breaking point, with usurping human will, life as God intended human souls to live it.

Love properly understood offers human beings eternal delight: Dante praises Beatrice as “she who imparadises my mind.” The erotic impulse in its heavenly purity immeasurably surpasses merely mortal love. It is Dante’s mind, not his body, that Beatrice arouses to the fullness of life. Giovanni Guasconti’s desire for his own Beatrice, by contrast, has an element of sinister factitiousness to its mind-spun passion. He cannot be sure if he loves or fears her more, or if indeed he loves her at all. Her moral grotesquerie sows confusion, and the man who wants her knows the pains of hell rather than the joys of paradise. She might have been a woman luminous in being as Dante’s Beatrice, were it not for the machinations of her mad scientist father. Hawthorne’s tale depicts the modern subversion of the venerable Christian truth that Dante’s epic represents, and laments the human wreckage that the new science in its heaven-storming mania causes.

So that he and she might both be “purified from evil,” Giovanni gives Beatrice Baglioni’s antidote to drink, intending to drink it after her, but she instructs him to wait and see how it works. Rappaccini comes out just then, and, looking upon the couple, revels in their union, which his science made possible. They shall stand apart from common humanity, he exults: “Pass on, then, through the world, most dear to one another and dreadful to all besides!” Rappaccini’s poison has so permeated Beatrice’s “earthly part,” however, that the antidote is fatal to her. As she fades, she asks her father why he has cursed her with “this miserable doom.” He throws her words back in her face.

“Miserable!” exclaimed Rappaccini. “What mean you, foolish girl? Dost thou deem it misery to be endowed with marvellous gifts against which no power nor strength could avail an enemy — misery, to be able to quell the mightiest with a breath — misery, to be as terrible as thou art beautiful? Wouldst thou, then, have preferred the condition of a weak woman, exposed to all evil and capable of none?”

This exhortation recalls Milton’s description of Eve’s fall, plotted by Satan as he feasts his eyes on her:

Shee fair, divinely fair, fit love for Gods,

Not terrible, though terrour be in Love

And beautie, not approacht by stronger hate,

Hate stronger, under shew of Love well feign’d,

The way which to her ruin now I tend.

Beautiful women are particularly susceptible to harm because men want them for their own sexual pleasure, or even, among the truly corrupt, in order to enjoy the violation of innocence; male hate can pose as love, or be intertwined with love. Eve’s lack of worldly hardness makes her easy prey for the Archfiend. After Eve’s fall, Milton implies, women had to cultivate the terrible in themselves, in order to safeguard their integrity and what remained of their innocence.

But there is the terrible and there is the terrible. Beatrice’s nature was inherently trusting and affectionate, so her father saw to it that she acquired a warrior’s armor. Rappaccini wanted his daughter to be proof against the predations of black-hearted men (perhaps knowing something of black-heartedness himself); he made her terrible as a Machiavellian conqueror and contrived to infuse a suitable young man with her own venom. Like Machiavelli, Rappaccini understands life as perpetual war, and if a woman is to triumph in the world — indeed, if she is not to be broken by it — she must be as capable of doing evil as a Machiavellian prince. Good men must be able to adopt evil as the need arises or they will come to ruin among men who are not good.

Beatrice is not a perfect offshoot of the Machiavellian mind, but a human creature whose nature has been perverted in the name of Machiavellian precept. Her riven being, like her father’s, proves the eternal truth that Rappaccini has devoted himself to controverting. She is her father’s child, but also her Father’s child, just as Rappaccini is God’s creature, however he might wish he weren’t.

Machiavelli raises the question “whether it is better to be loved or feared, or the reverse. The response is that one would want to be both the one and the other; but because it is difficult to put them together, it is much safer to be feared than loved, if one has to lack one of the two.” Rappaccini did not want Beatrice simply to be secure in her virtue; he wanted her to be fearsome as the most imperious prince, yet to know the joys of love. Not comprehending his daughter’s true nature, he demanded the impossible of her, and sought to shape her into a form after his own desire.

But Beatrice denounces this unnatural nature inflicted on her, reversing the Machiavellian counsel: “‘I would fain have been loved, not feared,’ murmured Beatrice, sinking down upon the ground.” In her operatic dying declaration, she says that she is ascending beyond the reach of her father’s designs and Giovanni’s disgust:

I am going, father, where the evil which thou hast striven to mingle with my being will pass away like a dream — like the fragrance of these poisonous flowers, which will no longer taint my breath among the flowers of Eden. Farewell, Giovanni! Thy words of hatred are like lead within my heart; but they, too, will fall away as I ascend. Oh, was there not, from the first, more poison in thy nature than in mine?

In her posthumous life she will most resemble Dante’s Beatrice, paragon of heavenly glory. Those left behind on earth must reckon as they can with her death and promise of ascension to the one true paradise.

The last word goes to Professor Baglioni, who “looked forth from the window, and called loudly, in a tone of triumph mixed with horror, to the thunderstricken man of science, — ‘Rappaccini! Rappaccini! and is this the upshot of your experiment?’” Rappaccini’s experiment is the same as modernity’s: to ignore the moral significance of the Fall as we bend its material consequences to our will, backtracking mankind into paradise.

In the old Eden, it was partaking of the Tree of Knowledge that brought about exile; here, it is the application of knowledge that makes the garden possible. Its author, Rappaccini, is not only man but god; his motherless offspring, like Eve born of Adam’s rib, is the instrument of ruin for another — but Beatrice is also an Adam, the garden’s first natural inhabitant, content but alone, for whom is brought a helpmeet. And Giovanni, that fickle Eve, finds Beatrice to be the serpent to him, ever so alluring but pure evil in effect — but it is also Baglioni, Rappaccini’s rival as Lucifer is God’s, who tempts Giovanni into fatal action, though tempting him with not poison but the antidote, away from sin and towards the light.

It is a hopeless, murky muddle, and the upshot is life lost, love destroyed, souls desolated, hell instead of heaven. Perfect innocence and purity of heart are not enough to navigate this harsh terrain, as Beatrice’s fate attests. Hawthorne does not leave us with an easy moral here. One cannot simply live by the laws of paradise on earth, either the heavenly paradise or the man-made one implicit in the scientific project. The relief that science promises of our exiled estate and the power promised by Machiavellian politics may seem to hold out as much hope as there is to be had.

But these twin pillars of modernity ignore entirely the heart and soul, an ignorance that bears disastrous fruit not only in the spiritual but even in the material realm. What potential redemption is there, then, in love? We don’t know from this story; no one is interested enough in Beatrice’s ideal to find out how far it leads. And the everlasting divine love of which human love is but a foretaste is even further out of reach, unknown if not unknowable.

One doesn’t know where or when or how the symbols of an allegory may surface in life. But to the extent that love is our salvation, that it is the greatest gift to man in life outside the Garden — better, perhaps, even than anything that was ours in the Garden — then refusing to look for it or honor it when it appears, building the world around it as if it did not exist, is to lose it for sure.