Every summer, on the way to the soon-to-be-infamous Jersey Shore, my family wound our way along the backroads of New Jersey through the forested, sparsely inhabited coastal plain known as the Pine Barrens. The pines rose out of the sandy soil in a dense, tangled mass on either side of the road, punctuated by lone peach stands and faded towns built around a single gas station. The pines could have been a wall, except that they moved, and threatened — what? To grow back over the road that cut through their demesne? To close the gaps that afforded flashing glances into the scrubby undergrowth and choked swamps? It wasn’t clear.

The shore was ours; this was not. This was old, and wild, and quiet, and there were things in it. Carnivorous plants grew out of the crumbly “sugar sand,” and the famously reclusive locals known as pineys lived between thickets of pitch pines and Atlantic white cedar. Abandoned iron-works had left deep, treacherous pools here and there. But there was something else, too; something with an elongated horsey head and scaly tail and bat wings; something that clomped on the roofs of bungalows and left cloven footprints in the snow. Its malice immense, its motives obscure, its appearances infrequent, that something was the Jersey Devil.

The Jersey Devil is such an ingrained cultural reference in New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania that it has an honorary role as the namesake of Newark’s hockey team. The legends are legion, but they converge to something like this: In 1735, an ill-fated colonial woman known as Mother Leeds, driven by one too many pregnancies, cursed her crowning thirteenth child. Moments after his birth, the Devil flew out of the chimney into the stormy night. Since then he has terrorized tram cars, harassed New Jersey residents, and haunted the imaginations of innumerable sleepovers. Unlike similar local spooks such as the West Virginia Mothman, his visitations are not associated with any particular purpose or omen.

If it’s not yet clear, the Jersey Devil is a repository for inchoate bogeyman fantasies and woodland panics. He is also a figure of affection and esteem. It is therefore with great sorrow that I must report that, according to two history professors at New Jersey’s Kean University, the Jersey Devil does not exist.

The title of Brian Regal and Frank Esposito’s recent scholarly debunking is The Secret History of the Jersey Devil: How Quakers, Hucksters, and Benjamin Franklin Created a Monster. It’s a clever appeal to the type of person who would be likely to believe the legend in the first place: seekers of hidden knowledge and secret histories.

What they claim to unveil is not a physical monster, or an undiscovered cryptid, but a lurid origin story hitherto buried in obscure archives. They explode the monster, but amend the outrage by substituting another in its place.

And it is a monster of a story. It begins in the ferment of early colonial America, where an odd, volatile mix of mutually antagonistic recusants and adventurers on the make were digging footholds along the eastern seaboard. The pine forests of New Jersey were vast, and they were not empty. They were an unbaptized world, home in the settlers’ imaginations to demons and witches and pagan gods, and Native Americans with whom the settlers had at best an unstable relationship. The Leni Lenape, by their own account, shared the Pine Barrens with a variety of spirits, including M’Sing, “a deer-like creature with leathery wings or a deer being ridden by a man,” as Regal and Esposito describe it.

Meanwhile, across the Delaware River, in the forests surrounding the Wissahickon Creek, a small group of pietists led by one Johannes Kelpius retreated into caves in order to scan the constellations for signs of Christ’s return. They practiced celibacy, and by some accounts, alchemy. Depending on whom you believe, the philosopher’s stone still lies somewhere at the bottom of the Wissahickon.

That astrology was a sometime Christian practice does not mean that it was looked on with universal approval. The period was suffused with spookiness, yet characterized by an uneasiness around the supernatural bordering on paranoia. And that uneasiness took on a sharp, polemically effective edge when weaponized in service of the constant religious and political controversies of the era.

Monstrous births, for instance, represented a judgment of God against an offender, usually the mother. A monstrous birth could mean an actual supernatural being — a changeling, a bat-winged devil baby — or simply a child born with some kind of major disability or deformity. Anne Hutchinson, the famous Puritan dissenter exiled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, gave birth — her sixteenth — to “a disturbing mass that bore little resemblance to a child.” (Centuries later, a New England Journal of Medicine article would claim this as New England’s first recorded molar pregnancy.) She also midwifed a female protégé’s severely deformed infant. This was proof of her sinful recalcitrance, in a kind of nightmare poetic justice. If a woman violated a boundary, it was precisely in her maternity that she could be punished. The fruits of her mind might be the locus of the offense, but it was in rejecting the fruits of her loins that divine authority could most effectively show its displeasure.

It is against this backdrop that Daniel Leeds — an Englishman who came to the New World in the 1670s, and the real heart of Regal and Esposito’s story — appears on the scene. Leeds would presumably be a relative of the infamous Mother Leeds, were there any evidence of the latter having existed. In the book’s imaginative telling, Daniel Leeds is a sympathetic figure. He seems to have had visions of Christ and ecstatic religious experiences from youth, which eventually impelled him to join the Quakers. He also comes across as a man stumbling from one ill-fated project to another, seeking his great work.

The first of these projects was the Leeds Almanac, whose first edition appeared in 1687. Printing was still expensive, and so household almanacs functioned as a kind of catch-all for useful and curious knowledge, a printed Wunderkammer. Like many others, Leeds’s included planting times and meteorological forecasts, local news and topical essays. But it also dealt with medical astrology, the belief that the heavens not only governed human temperaments and world affairs, but parts of the body — Scorpio was in charge of the genitals, Leo governed the heart, bloodletting was most favorable when the moon was in Cancer. Because of the almanac’s astrological emphasis, Leeds’s New Jersey meetinghouse quickly bought up and destroyed all the unsold copies of the first printing, and required Leeds to publicly apologize.

His next foray was the Temple of Wisdom, a commonplace book — essentially an aggregation of his readings in philosophy, astrology, theology, and magic — with the ambitious stated scope of all extant metaphysical and scientific knowledge. It is difficult, when astrology is at best a niche parlor game, and at worst an easy tell for woo-woo gullibility, to convey the unity of Leeds’s project. He longed to make his fellow colonists aware of Virgo’s importance to good digestion, and convince them that the earth orbited the sun. The boundaries between natural history and occult knowledge were blurry; or rather, what we now think of as occult knowledge was seen as simple cosmological inquiry. The world was strange and wonderful, and its contours could be mapped in all directions.

The Temple of Wisdom did no better among the Quaker elite than its predecessor, and Leeds became embittered against his one-time friends. By the early 1700s he was an Anglican. His literary powers were mostly employed in penning vitriolic screeds against the Quakers, and in support of an increasingly unpopular royal governor. Eventually, they accused him of being Satan’s own harbinger.

A written account of what we now call the Leeds Devil does not show up until 1859. But in Regal and Esposito’s telling, Daniel Leeds became the Jersey Devil through a kind of generational folkloric alchemy, primed by the common rhetorical habit of attributing witchcraft, deviltry, and monstrous births to one’s enemies. After Daniel Leeds died, his son Titan became the target of similar charges, leveled by no less a personage than Benjamin Franklin. The Jersey Devil’s alleged birth in 1735 coincides, sort of, with the death of Titan Leed in 1738. Thus, the authors hypothesize that the rumors attached to the Leeds family — of being ghosts and emissaries of Satan — coalesced into a single myth as memories of the real Leeds family faded.

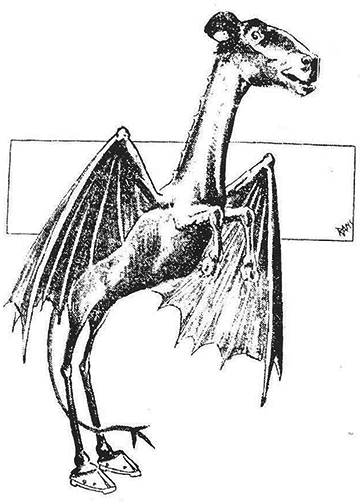

There are unfortunately no written sources of the Leeds Devil contemporary with its legendary birth, so it is difficult to say what the story might have looked like in its earliest forms. But the first known written description of the Leeds Devil, published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1859, roughly matches the creature of current fame. It had a horse’s head, a serpent’s tail, and a bat’s wings. It haunted the woods, abusing maids and eating children unfortunate enough to cross its path.

The Leeds Devil and the later Jersey Devil have had a variety of appearances, but they are usually a mashup of elements of real and mythical beasts, with wings, a tail, and some reptilian aspect. Regal and Esposito suggest that another source for the features of the modern legend may have been the Leeds family crest, which features a cockatrice (a rooster-like monster) as well as three figures with wings, clawed feet, and pointy tails. The now-classic image of the Jersey Devil, based on a 1909 drawing, is a gaunt flying horse, with the wings of a bat, the head of a horse or a kangaroo, and a forked, devil’s tail.

The Jersey Devil of today’s folklore appears to be the child, on the one hand, of the nineteenth century’s booming and undisciplined interest in natural history, and on the other, of a distinctly American ability to turn anything under the sun into a side-show hustle.

In 1817, the Linnean Society of London formed a committee to study the sea monster allegedly washed up on the shores of Gloucester. In 1841, Richard Owen identified dinosaur fossils for the first time. And in 1835, the New York Sun published an account of the moon as seen through an inventor’s high-powered telescope: a surface covered in pleasure gardens, inhabited by giant bipedal beavers and flying, bat-like hominids.

The Pine Barrens had meanwhile withered from a thriving colonial hub into the ragged edge of civilization described by John McPhee in his famous 1967 book on the region: “Getting — or staying — away from everybody is a criterion that apparently continues to mean as much to many of the people in the pines as it did to some of their forbears who first settled there.”

From the mid-1800s onward, more and more references to something wicked stalking the isolated cottages in the pines began cropping up. Finally, the “real” Jersey Devil — actually a much-abused kangaroo — made its most famous appearance in 1909, at the Ninth and Arch Street Dime Museum in Philadelphia. After that, Jersey Devil mania reached fever pitch, and the authors spend much of the book’s second half carefully tracing and debunking the creature’s media appearances. Their scholarship is thorough, and the story they tell is so textured, so full of moving parts and curiosities, that it cannot fail to please even the prejudiced and obdurate readers (me) who believe axiomatically in the creature’s existence.

The authors never quite manage a smoking gun, a moment when Daniel Leeds transforms into the creature who first appears in print as long-established folklore. But the Leeds family narrative is no less valuable for that. The only other misstep is a forgivable one: For understandable reasons, the authors slightly oversell the degree to which their debunking is news. It is true that on gimmicky shows like MonsterQuest, the Jersey Devil is treated as no more or less believable than, say, Bigfoot. But among more serious cryptozoologists and chroniclers of the paranormal, such as Charles Fort, the creature is widely considered one of the least grounded in historical or natural evidence.

If the Jersey Devil legend has survived, it is not because the facts bear it up. It is because the creature is New Jersey. If there is a more unclassifiable and more mismatched organism than something with a horse’s head and a dragon’s wings, it is the Garden State. Home to mobsters, millionaires, and bog farmers, it breeds celebrity monsters for every age. Its veneer of McMansions and strip malls seems inescapable until you realize how tenuous the veneer is. Stray just a little from Bergen County’s estates, and you fall into a cauldron of oddity, from roadside rodeos to the worn-out perma-carnivals of Atlantic City, to the lonely clapboard houses and colonial ghosts deep in the pinelands. And underneath all that are the Pine Barrens themselves, the primeval aquifer feeding all New Jersey’s native witchcraft. “The picture of New Jersey that most people hold in their minds is so different from this one that, considered beside it, the Pine Barrens, as they are called, become as incongruous as they are beautiful,” McPhee writes. The pines make all of New Jersey a borderland. Refracted through them, the strip malls themselves take on a ghostly and insubstantial air.

The Jersey Devil fits his home so well that it is easy to believe he was born and bred to it, one stormy night three centuries ago. He is its mascot, but more than that, he is the dragon marking the edge of the map, proclaiming, Here Be Monsters.

Belief in the Jersey Devil does not require any appeal to nefarious interests or hidden agents. But cryptozoologists and conspiracy theorists do share some broad interests: a love of secrets; an intellectual contrarianism; a preference, at least, for the bizarre over the easily explained. According to Rob Brotherton, these tendencies correspond to psychological traits that all of us share to some degree.

Brotherton’s book, Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories, is a more sympathetic project than it might first appear. Brotherton, an academic psychologist, is not out to paint conspiracy theorists as wild-eyed basement-dwellers. In fact, the book starts by debunking common myths. Women are no less likely than men to sign on to conspiracy theories, the young are just as gullible as the old, and education has only a small correlation with skepticism. And, Reddit notwithstanding, the Internet does not seem to have ushered in a golden age of conspiracy theories. He also notes, justly, that some conspiracy theories are simply the default suspicion of people whom society has routinely and often deceitfully brutalized.

One truism remains standing: People who believe in conspiracy theories don’t do so by evaluating, accepting, and discarding each as independent propositions with separate merits. Conspiracy theorizing constitutes a broad worldview, and the degree to which you are conspiracy-minded determines the likelihood of your accepting any given conspiracy. Conspiracy-mindedness as defined by Brotherton includes a mix of personal characteristics, accidental circumstances, and universal drives. Individual traits like paranoia and openness make a person ripe for conspiracism. Powerlessness, with a corresponding need to assign agency somewhere, further disposes a person to conspiracy thinking. And universal mental tics like proportionality bias seal the deal:

When the outcome of an event is significant, momentous, or profound in some way, we are inclined to think it must have been caused by something correspondingly significant, momentous, or profound. When the consequences are less far-reaching, more modest causes appear more plausible. Put simply, we reckon big things have big causes.

Brotherton does not provide a hard and fast definition of a conspiracy theory. It would be difficult to do so. Instead, he offers a working definition based on six elements. The conspiracy theory starts with an unanswered question, and the appeal of the theory depends on incertitude. Its internal logic dictates that nothing can be taken at face value, and that all phenomena are the result of deliberate machinations by an agent. Conspiracy theorists hunt for anomalous information: Their accounts tend to explain more than the accepted narratives, since they address both the basic facts and the inevitable gaps. And they tend to frame their accounts as a grand battle between good and evil (there are very few conspiracy theories involving small-time grifters). Finally, they operate by a “heads I win, tails you lose” logic. If there’s a lack of evidence, something’s been covered up. If contrary evidence appears, well, that’s exactly what They would say.

The loose working definition is necessary, since the categories of theorist and skeptic tend to break down when pressed too far. There’s the man who believes that the government is engaged in a vast and sinister project of promulgating conspiracy theories. There are the political commenters whose concern about fake news has rapidly descended into breathless fear-mongering about Russians amongst us. And there’s the odd indeterminacy of fabricated conspiracy theories, like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. An insane fantasy spurred and widely popularized by racial prejudice, the content of the theory is false — but the theory itself was birthed by an actual conspiracy, a deliberate forgery propagated by figures no less powerful than Henry Ford and the Nazis to create a false narrative and fan political persecution of the Jewish people.

If conspiratorial thinking is a widespread feature of human thought, it can be difficult to pinpoint where exactly “conspiracy theory” becomes a pejorative. Plain falsehood, and the occasional links to violent extremism are clear concerns for Brotherton, as is the of role conspiracy theorizing in pernicious beliefs like those of the anti-vaccine movement. Brotherton also worries over their encouragement of political disengagement — he offers the rather facile example that people emerging from a movie theater after watching Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) were less likely than before they went in to say they would vote or get involved in an upcoming election.

But for Brotherton, there is a question that lies even deeper than the truth or falsehood of any particular theory, a question about the psychological traits that attach us to them. Each trait is valuable and even necessary to human survival, but left unchecked, impedes rationality. Again and again in the book, we hear conspiracy theories explained by reference to proportionality bias and its myriad siblings. This book is, to some degree, the Daniel Kahneman take on conspiracy theories. And though Brotherton takes pains to distance himself from those who sneer at conspiracy theorizers, this seems largely to be because he views them as but the most pronounced examples of the lowly sub-rational condition in which all humanity wallows.

“Rationality,” though, is also never clearly defined. For instance, the author describes a game in which two parties must divvy up $100 between them. One decides how to split up the money, and the other can reject the offer, in which case they both walk away with nothing. Even though an unfair split will still leave both players with more money than they originally had, most people will reject a lopsided offer. “Foregoing the dollar to punish a greedy Ultimatum Game player might deviate from pure rationality,” Brotherton writes, “but it makes sense in a world where letting cheaters prosper could spell trouble for everyone.” But why is this a deviation from pure rationality? Why should prioritizing immediate monetary gain be more rational than preventing cheaters from prospering?

The problem with Brotherton’s book, as informative and amusing as it is, lies deeper than a few glib assumptions about rationality and self-interest. For all its expertise on conspiracy theories and fringe beliefs in general, the book never really describes the quality of their attraction, only the mechanisms that enable or reinforce it. The nearest attempt — borrowing words from journalist Damian Thompson — is the throwaway line that “unconventional beliefs can be ‘a passport to a thrilling alternative universe in which Atlantis is buried underneath the Antarctic, the Ark of the Covenant is hidden in Ethiopia, aliens have manipulated our DNA, and there was once a civilization on Mars.’” But, Brotherton reminds us, we generally don’t believe things just for the fun of it.

Fringe beliefs, though, can be tremendously fun. Brotherton underestimates how near the desire for knowledge is to a species of play — not contemplation, nor creation, but a restless activity driven wholly by its own internal ends. For that matter, he undersells human intellectual capacity in general. Proportionality bias will cause you problems if you aren’t aware of it, and psychologists do valuable service in articulating various pitfalls of this kind. But proportion is in fact important to the structure of the world. This insight lay behind the ancient music of the spheres, the notion that the mathematically proportioned movements of heavenly bodies constituted a harmony, akin to song we could not hear.

That the movements of the human mind, its bent for narrative and order, might correspond to something real besides raw evolutionary fitness simply does not compute for Brotherton. And once you undersell the capacity of the human mind to know and love the world, you have lost the thread on both conspiracy and cryptozoology. However toxic certain strains are, both are a kind of world-loving. Conspiracy theories obsesses over human history and insist that it can be known, not as a collection of data points and mass social tendencies through time, but on a human-sized stage with real human actors. Cryptozoology taps into a tradition of natural history in which nature is wild, and jealous of her secret oddities. Its amateurism and eagerness towards all phenomena distinguish it from science, but it is precisely in those qualities that its riches lie. It does not assume an enchanted world, precisely, but a world that has never lost its edges, where discovery has never ceded precedence to technical tinkering.

At the cognitive fringes you’ll find not just pathology, or even psychological mechanisms, but an instinct for cartography. The world is strange and wonderful, and its contours can be mapped in all directions.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?