If we want to improve our digital discourse and clean up our social media platforms, then we must begin by understanding how these platforms influence us, and in particular what their “social” nature is. Their influence on us is largely invisible yet also pervasive, which is why we often fail to see how they shape us.

As an example of this failure, consider research in 2013 led by computer scientist Karrie Karahalios. Her team investigated people’s awareness of the algorithm that determines which updates by our Facebook friends we get to see on our feeds. The researchers found that 25 of the 40 Facebook users in the study were unaware or unsure that their feeds were being filtered at all. As Time magazine reported:

When the algorithm was explained to one subject, she compared the revelation to the moment when Neo discovers the artificiality of The Matrix. “We got a lot of visceral responses to the discovery when they didn’t know,” Karahalios says. “A lot of people just spent literally five minutes being in shock.”

What this story shows is the need to ask not only what Facebook is, but also what Facebook means to us socially and culturally. Though it should come as no surprise that users would not understand how Facebook’s algorithm works, it should give us pause that the discovery of its very existence can be experienced as viscerally as Neo discovering that the world is an illusion. This is why we must attempt to get clear about the nature of Facebook, for Facebook has become so large that for many it is no longer experienced as merely a site on the Internet but as part of the fabric of everyday reality.

One way to examine the nature of Facebook is to distinguish all of the various forms Facebook is able to take. This will help us to clear up the confusion that occurs whenever we take for granted that everyone talking about Facebook is talking about the same thing.

For example, reports about Facebook’s involvement in scandals surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election — scandals ranging from distributing misinformation to abusing user data — have caused alarm about the dangers it poses to democracy worldwide. But it’s all too easy in these scandals to focus on Facebook’s privacy practices and on its public image, and on Mark Zuckerberg testifying before Congress, while failing to think about how our own use of Facebook is shaping our relationships or our role in the public sphere.

Facebook exists in many forms. To talk about only one form of Facebook’s influence — for example, its own repeated violations of user privacy — is to overlook the other forms of influence — for example, its ability to empower users to invade each other’s privacy. Hence we can understand why persistent criticisms of Facebook, and even the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the massive data breach in 2018, have had little to no impact on Facebook’s long-term business performance. Both revenue and user numbers were higher than expected by the end of last year.

To better understand the different forms of Facebook’s influence it is useful to turn to an analysis by philosopher of technology Don Ihde. In Technology and the Lifeworld (1990), he distinguishes different types of relations between humans and technology and argues that technologies are not merely means to human ends but rather shape how humans see the world and act in the world. Ihde’s categories for these different relations help us to see the various forms of Facebook’s influence on us.

Dependency: Facebook as profile

Users experience Facebook as a personal site that combines the functionalities of blog posts, emails, event listings, message boards, classified ads, and photo albums all in one place. This can make Facebook seem like an online extension of one’s offline communication. We can describe this in terms of what Ihde calls “embodiment relations” between humans and technology, which occur when technologies that improve human bodily abilities become part of our embodied sense of self. For example, a pair of glasses can improve eyesight, but at the same time the glasses themselves come to feel like an invisible extension of the eyes, focusing attention on what can be seen and away from the role the glasses play in shaping what can be seen.

Facebook as profile works a little bit like glasses: It enhances our ability to communicate with others and focuses our attention on that communication — but this attention leads us to lose sight of the role Facebook plays in shaping that communication. And so users tend to think of Facebook as merely a very powerful communication tool that reaches lots of people, while ignoring that Facebook helps determine what and how we communicate, which hardly resembles offline communication. Status updates, comments, likes, shares, memes, emojis, and GIFs — these are very particular types of online communication that are not simply amplified versions of what we’d say to a friend in person. But it’s easy to forget this, and instead to think of Facebook as just an effective way of communicating with more people.

In embodiment relations, technologies seem to become a part of us. They empower us as we get used to relying on them, which leaves us open to dependency. When we use Google Maps to find our way around, we think of it as simply a convenience, but if the smartphone battery dies, we are suddenly forced to realize how lost we are without access to Google Maps. Likewise, as we grow more accustomed to communicating through Facebook, we become more dependent on it, becoming so attached that we think we could not delete our account even if we wanted to, since to do so would be to lose our ability to communicate with our “friends.”

Misinformation: Facebook as platform

Users also experience Facebook as an expansive network, as a way not only to stay in touch with existing friends and family, but also to meet new people, to interact with public figures we don’t personally know, and to stay informed about current events. We can describe this in terms of what Ihde calls “hermeneutic relations,” which occur when technologies expand our abilities to perceive and interpret the world by allowing us access to parts of it that we could not otherwise access. For example, a device for detecting radiation, like a Geiger counter, can monitor radioactive materials and send its signals to computers that translate the signals and display them on control panels human users can read — but we come to forget about the roles of these machines and just say that we are monitoring the radioactive materials.

Facebook expands our ability to access new information and focuses our attention on that new information, which leads us to lose sight of the role it plays in our gaining that access. We might think of Facebook as a blank online space for information-gathering and information-sharing between users, while ignoring that Facebook itself shapes what information we receive — as when its newsfeed algorithm prioritizes some posts while hiding others — and how we receive it — through posts, ads, alerts, invites, requests, and pop-up notifications.

In hermeneutic relations, we experience technologies as part of the world. Because we typically trust that they are relaying information about the world that is accurate, this leaves us open to misinformation, whether arising from nefarious actors or flaws in the technology’s presentation of information. As Ihde points out, one of the reasons the nuclear plant at Three Mile Island experienced a partial meltdown was that the control panels were poorly designed, which led the human operators to misread them. Likewise, on Facebook, the content of the new information we receive often can’t easily be interpreted on its own, because it is presented to us in a way that lends itself to misreading — like when a headline appears out of context in someone’s post, or an image appears shorn of the caption that gave it necessary context. This is why “Fake News!” warnings put us in a situation similar to seeing the “check engine” light come on in a car: We are unable to know if the problem is the engine or the light, and so we just keep driving hoping that nothing will go wrong.

Manipulation: Facebook as corporation

Users interact with Facebook even when they might not be aware of it, for example through the other services owned by Facebook, Inc., such as Instagram and WhatsApp, and through the services it sells, notably advertisements designed and targeted based on user data. We can describe this relationship to technology in terms of what Ihde calls “background relations”: Technologies can operate behind the scenes of everyday life while being an integral part of it. For example, indoor lighting systems allow us to work in spaces without natural light, and are designed to operate unnoticed so that we can do our work without having to think about the lighting, beyond turning it on and off.

Facebook is of course able to provide users with the “free” services of Facebook-as-profile and Facebook-as-platform only because of its ability to find other ways to monetize its services, like selling ads. But, as a background relation, its monetization capabilities are never meant to be made visible to users. We are meant to become accustomed to seeing Facebook “like” buttons appear on websites where we shop or read the news, and to seeing ads from those same sites appearing in our Facebook newsfeed, without worrying that we are being followed around the Internet by the corporation.

In background relations, the operations of technologies are hidden from view, leaving us open to manipulation. Lighting systems are no longer merely illuminating workspaces, but are now being designed to improve moods and productivity, which can lead workers to think they like their jobs better when in reality they just like the lighting better. As with such lighting systems, we notice Facebook’s corporate “partnerships” only when something out of the ordinary occurs, like in the Cambridge Analytica scandal. But what should concern us is not the scandals. We should instead be concerned about how much of ordinary life is now dependent upon the behind-the-scenes operations of Facebook-as-corporation. Because so much of Facebook’s activity is in the background, privacy-conscious people can think of themselves as free from Facebook if they do not have an account, even though they may continue to use WhatsApp and Instagram. Or they may have friends, relatives, colleagues, and acquaintances, or businesses they frequent, that continue to share information about them with Facebook so that Facebook can create what has come to be known as a “shadow profile” — the data Facebook has of people who don’t have accounts.

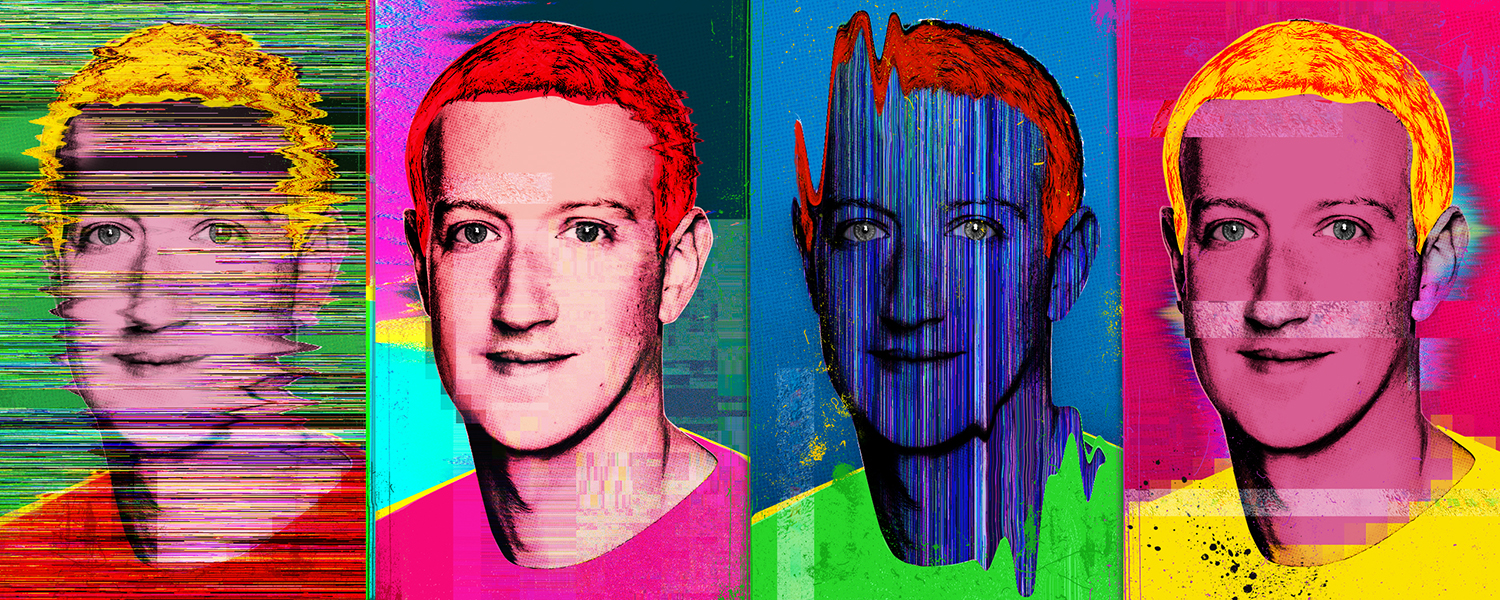

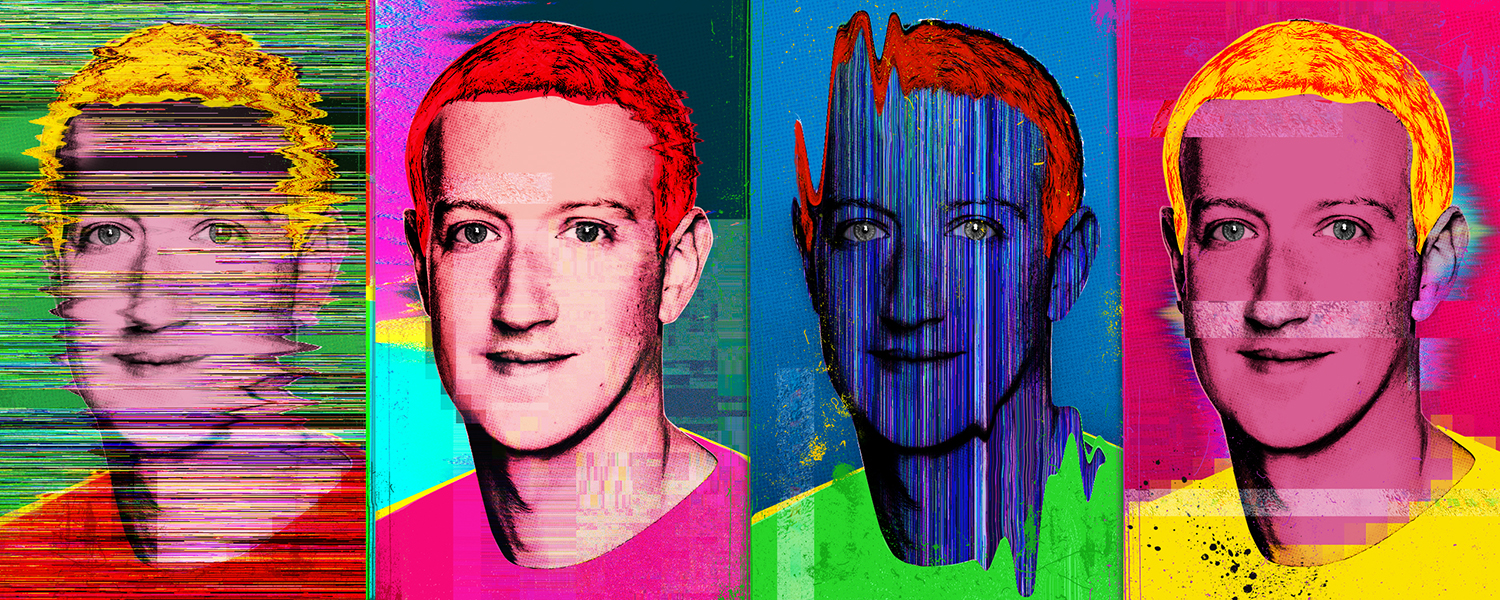

Distraction: Facebook as Zuckerberg

Facebook interacts not only with its users but also with the world, whether through Mark Zuckerberg’s personal posts, public apologies, and media interviews, or, more recently, through his testimonies before Congress. We can describe this interaction between humans and technology in terms of what Ihde calls “alterity relations,” which occur when technologies draw attention to themselves by simulating the actions of living beings — “alterity” meaning “otherness” — leading us to attribute lifelike qualities to them. For example, “robots” such as Siri or Alexa talk like humans, which leads us to interact with them as if they were humans, so much so that when they make us happy or angry we act as if they were directly responsible, forgetting for the moment the role of the engineers who programmed them.

Mark Zuckerberg is not a robot, but it’s worth taking seriously that some people like to imagine he is. For, like a robot, Facebook-as-Zuckerberg still functions as an alterity relation, because he focuses our attention away from the world, in particular away from the world created by Facebook-as-corporation. In much the same way that people focused on Steve Jobs or Bill Gates rather than on Apple or Microsoft, Mark Zuckerberg is able to keep the public focused on him, thereby distracting us for example from questions about how Facebook influences us behind the scenes.

In alterity relations the technologies are meant to occupy our attention, and because they can entertain us or enrage us, they leave us open to distraction. The augmented-reality game Pokémon GO was hailed by many as a video game that could get people to enjoy the outside world, and yet players became so oblivious to the world around them and got into so many accidents that Pokémon GO had to start reminding them to “stay aware of your surroundings at all times.”

Likewise, whether people love or hate Zuckerberg, they are distracted by Zuckerberg. Whenever he puts out statements about his vision for Facebook, the media and the public interpret and debate them as signs about what Facebook is going to do next. This helps to maintain the illusion that Facebook is the creation of a disruptive tech visionary rather than a multinational corporation that operates with much of the same capitalist ambitions and practices as any other multinational corporation. And, most importantly, this helps to focus our attention away from what Facebook has done in the past and what it is doing in the present, including its scandals, remaining instead focused solely on what Zuckerberg has planned for the future.

Because Facebook occupies a prominent role in the public sphere, it has a responsibility to reform its practices, making them more transparent, as this would help users combat the dangers created by Facebook’s various forms of influence: misinformation, manipulation, dependency, and distraction. We must realize, however, that the public push for greater transparency, even through regulation — which Zuckerberg himself has acknowledged is “inevitable” — may itself serve to distract us rather than to help us, as this would be a technological solution to a larger social problem. The attempt to fix a social ill technologically is precisely what led to the problem we have with social media platforms like Facebook in the first place. Just as the desire to get around cities more easily and cheaply led us not to reform outdated urban infrastructures but instead to create Uber, so the desire to be more social led us not to question whether technological progress was making us anti-social but instead to create Facebook and Tinder.

We must therefore not be satisfied with merely regulating Facebook’s role in the public sphere. We must instead ask what it is about the public sphere — and about our own lives — that has allowed Facebook to occupy such a prominent role. If Facebook is filling a void in our public and personal lives, then fixing or even replacing Facebook is no better than dealing with a sinking ship by trying to stay dry rather than by trying to stop sinking.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?