In his 1961 address to the annual convention of the National Association of Broadcasters, Newton Minow famously offered a pessimistic assessment of America’s most exciting new industry. Television, declared Minow, was turning into a “vast wasteland” of “blood and thunder” and “formula comedies.” Minow, the recently appointed head of the Federal Communications Commission, specified only one weekly series he found “dramatic and moving,” a hopeful sign of what broadcast television could become. This was The Twilight Zone, which its creator and chief writer, Rod Serling, described as “a series of imaginative tales that are not bound by time or space or the established laws of nature.”

The Twilight Zone won numerous industry awards and wide critical praise during its five-season run from 1959 to 1964 on CBS, confirming Serling’s place as one of the most prolific and innovative writers and producers to emerge from the live-drama era of the 1950s, television’s original “golden age.” But by the time he died in 1975, Serling was probably less well known for his writerly creativity than as the host of a quiz show and as the face of TV commercials for cigarettes and cars.

What happened? How did the man who longed to be — and arguably was — television’s answer to Arthur Miller end up instead as an edgier version of Ed McMahon?

Exhaustion played a part. In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace, Serling said he worked twelve to fourteen hours a day on The Twilight Zone, seven days a week, even as he kept other projects simmering. “When I bend down to pick up a pencil,” he joked on another occasion, “I’m five days behind.” At least one of his biographers, Joel Engel, also blames a growing taste for what Serling himself called the “crazy, pink, whipped-cream world” that media fame opens up. Serling’s late career as a “commercial huckster,” “ham actor,” and “professional celebrity,” Engel writes in his insightful Last Stop, the Twilight Zone (1989), grew out of an “addiction to fame — and fortune — that cost him his chance at true greatness.”

But it is also true that by the time The Twilight Zone left the air, the trends that had worried Minow in 1961 were even easier to discern. During the 1950s the commercial networks were still burnishing television’s image, hoping to prove that this new and relatively expensive device was far more than an “idiot box” or a “boob tube.” Commercial television supplied culture as well as vaudeville — Shakespeare and Beethoven as well as Sergeant Bilko and Gorgeous George. In the late 1950s, when The Twilight Zone debuted, Omnibus was still on the air; that show had aired lectures, interviews, and performances of original screenplays as well as abbreviated versions of such classic works as King Lear and La Bohème. Richard Burton appeared as Heathcliffe in the DuPont Show of the Month production of Wuthering Heights, and Leonard Bernstein gained national fame because CBS broadcast his Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic from Carnegie Hall.

But by 1970, if not before, almost none of the TV industry’s leaders really believed, with Minow, that they were “public trustees” who should have faith in “the people’s good sense and good taste,” shunning “a relentless search for the highest rating and the lowest common denominator.” Television now demanded celebrity, not literary ability — probably the main reason Serling shifted from scriptwriting to shilling, lending his distinctive persona to the makers of toothpaste and beer and many other products. Of course it was ironic that the man who once compared television’s endless advertisements to “traveling snake-oil shows” should end up as Madison Avenue’s go-to guy. But it was probably inevitable too, given the economic factors and programming assumptions shaping network TV. “We had tilted at the same dragons for seven or eight years,” Serling said about the early television dramatists who, like himself, had battled publicly for quality TV. “And, when the smoke cleared, the dragons had won.” Serling’s idealistic career, turned tacky in the end, reflects the direction of American television during its formative years.

Rodman Edward Serling, born in 1924, grew up in Binghamton, New York, the son of a butcher who was also an amateur inventor whose most inspired idea — the “frankburger,” a hamburger-shaped hot dog — somehow failed to catch on. By his own account Serling enjoyed a pleasant childhood. He was popular and athletic, active at the Jewish Community Center and at Binghamton Central High School, where he was a member of the debate team and a frequent performer in student plays. A lingering nostalgia informs several well-known Twilight Zone episodes, including “Walking Distance,” in which a workaholic advertising executive, a stand-in for Serling himself, goes “looking for sanity” in his old hometown, where he finds himself face-to-face with his boyhood self and discovers that, alas, one cannot escape the present by retreating into a vanished past. It is one of Serling’s favorite themes on The Twilight Zone, which deals frequently with failure, regret, and loss. This “sentimental streak,” writes his daughter Anne Serling in As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling (2013), was “almost as intense as his crusading moralistic streak.”

In 1943 Serling joined the U.S. Army’s 11th Airborne Division. Standing five foot four, he barely qualified. Assigned to the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, Serling saw action in the Philippines during the fierce closing months of the war. He took part in the Battle of Manila, where American casualties were high. Serling was awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star, and, according to his daughter, when he returned to the States he suffered from what used to be called “shell shock.” In her memoir she writes that, as a child, she often heard her father scream out in the middle of the night. For years in his dreams he continued to fight the Japanese. He turned to writing, he admitted, as “a kind of compulsion,” a “terrible need for some sort of therapy.”

Attending Antioch College on the G.I. Bill, Serling studied literature and imitated Hemingway: “Everything I wrote,” he later recalled, “began, ‘It was hot.’” Serling’s other models included the radio dramatist Arch Oboler, whose highly inventive horror series Lights Out almost certainly helped inspire The Twilight Zone. After graduating in 1950, Serling worked as a copywriter and, in his spare time, managed to place some of his own rather melodramatic scripts with popular radio serials like Dr. Christian, about a small-town physician. As his skill and confidence improved, Serling turned to television, where an urgent demand for original material allowed a now-legendary cadre of young writers — which also included Paddy Chayefsky and Reginald Rose — to start their careers.

Serling quickly sold television plays to the better New York-based anthology programs. His first real hit, “Patterns,” was a character-driven big-business drama broadcast live on the Kraft Television Theatre; it was, New York Times critic Jack Gould wrote a few days after its broadcast, “one of the high points in the TV medium’s evolution.” In that age before reruns, “Patterns” became the first television drama to get a second airing — by having the original cast reassemble a few weeks later for a second live performance. It earned Serling his first Emmy, and would later be adapted into a film. Serling soon succeeded again with “The Rack” (1955), about an American soldier “brainwashed” as a prisoner during the Korean War; this teleplay, too, was adapted into a movie, starring Paul Newman. Serling’s second Emmy came for “Requiem for a Heavyweight” (1956), a grimly sentimental portrayal of an aging prizefighter scrapping to save his dignity in a sport long marked by corruption and betrayal. A 1957 adaptation of Ernest Lehman’s short story “The Comedian,” which featured Mickey Rooney as a cruel and vulgar TV funnyman — a sort of sadistic Sid Caesar — brought Serling Emmy number three.

Young and articulate, Serling was widely interviewed and profiled for many leading newspapers and magazines. “All of a sudden,” he remembered, “with no preparation and no expectations, I had a velvet mantle draped over my shoulders…. Like a good horse, or a swivel-hip halfback, I was the guy to watch.” Offers flowed in, including offers to write for film, but somehow it never really worked out. Engel suggests that Serling was too cocky and impatient to find “the time and care it takes to develop a worthwhile film.”

So television remained Serling’s medium, and he used his new stature to emerge as one of TV’s most eloquent champions. For example, in a 1957 essay introducing a collection of four of his scripts, Serling argued that television was ideal for the sort of smart, provocative drama that he, Rose, and Chayefsky, among others, aspired to write. The movies may have had CinemaScope, but the small screen offered “intimacy.” The teleplay was nothing less than a “new art form” featuring recognizable people in everyday settings. Television drama relied on close-up shots, facial studies, carefully chosen words; it “won’t take stark villainy or lily-white heroism,” as he put it in a 1955 newspaper article. The best television dramas — he was especially fond of Chayefsky’s Marty, about a homely butcher looking for love in the Bronx — dealt “in all the grays that make up character” in an effort to say something meaningful about the human condition. Even “a few intellectual diehards,” Serling observed, had begun to believe that “a television play could come close to the legitimate theater, and even surpass it sometimes in terms of flexibility.” At its best, TV combined “the immediacy of the living theater” with “the flexibility of the motion picture, and the coverage of radio.”

Radio, however, supplied an unfortunate precedent. For decades the big radio networks — CBS and NBC — had dominated the medium’s programming, providing endless hours of drama as well as news, sports, and information. But almost no one, noted Serling, thought of radio as a medium for literary art. With the exception of Oboler, Norman Corwin, and a few others, radio’s writers were complete unknowns. Even within the industry, Serling observed in that 1957 essay, they were considered “hacks” whose scripts were mere “appendage[s]” to sales messages from Ivory Soap, say, or Fleischmann’s Yeast. For the most part radio drama “aimed downward”: it became “cheap and unbelievable” and “willingly settled for second best.”

Serling worried that television would go the way of radio. The television sponsor also “invests heavily” in a mass “organ of dissemination,” and without him, Serling conceded, that organ would “wither away.” But Serling wanted sponsors to think of television not as an animated billboard but a great national stage where dramatic entertainment could incorporate a more mature interest in social issues and more subtle themes. Like Minow, Serling urged the medium’s leaders and funders to cultivate and liberate literary talent, much as certain theatrical producers or the funders of great orchestras saw themselves primarily as champions of crucial cultural institutions rather than as salesmen and entertainment profiteers. Too often, Serling complained, television’s best programs were interrupted by “raucous singing jingles that dent the ears.” As a result, “the audience must then make its own mental and emotional realignment to ‘get back with’ the sole object of its intentions. That it can do it at all is a tribute to mass intelligence and selectivity.” “No dramatic art form,” he added, “should be dictated and controlled by men whose training, interest and instincts are cut of entirely different cloth.” This, he wrote, was rather like letting a beer baron manage a professional baseball team simply because his ads bankrolled their televised games.

From the start, however, Serling faced intrusions great and small. In one early episode of The Twilight Zone, for example, a sponsoring coffee company protested a scene in which a ship’s officer called out for tea. Far worse, however, was an incident a few years previous involving a teleplay Serling wrote for a weekly show sponsored by U.S. Steel. Serling’s script alluded to the 1955 lynching murder in Mississippi of the black fourteen-year-old Emmett Till. At the behest of the sponsor, the script was “vitiated, emasculated,” Serling remembered, so that all references to racism in the South were generally expunged. Here is how Marc Scott Zicree recounts the incident in his Twilight Zone Companion:

The plot concerned a violent neurotic who kills an elderly Jew and then is acquitted by residents of the small town in which he lives…. U.S. Steel demanded changes in the script. The town was moved from an unspecified area to New England. The murdered Jew was changed to an unnamed foreigner. Bottles of Coca-Cola were removed from the set and the word “lynch” stricken from the script (both having been determined “too Southern” in their connotation). Characters were made to say “This is a strange little town” or “This is a perverse town,” so that no one would identify with it. Finally, they wanted to change the vicious, neurotic killer into “just a good decent, American boy momentarily gone wrong.”

Serling was left feeling he was “striking out at a social evil with a feather duster.”

A later script for Playhouse 90, also based on the Emmett Till story — this time retelling it in a Western setting — was altered as well. “They chopped it up like a roomful of butchers at work on a steer,” Serling complained. Years later, he would say that, “From experience, I can tell you that drama, at least in television, must walk tiptoe and in agony lest it offend some cereal buyer from a given state below the Mason-Dixon.”

In politics Serling was a Kennedy Democrat ardently supportive of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Hollywood chapter of Citizens for a Sane Nuclear Policy. After Kennedy was assassinated Serling wrote a short documentary for the U.S. Information Agency; it was intended to portray — especially for foreign viewers — the new president, Lyndon Johnson, as a gruff but humble man, a paternalistic populist who, with the help of the United Nations, would work to abolish poverty and end war. By 1968, like many others in Hollywood, Serling was denouncing Johnson’s Vietnam policies while hailing “the goals and aspirations of America’s young.” And yet, as Anne Serling recalls, her father wore his silver paratrooper’s bracelet for the rest of his life, calling himself a patriot of the old school. “I will salute our flag and stand for our anthem,” he told a college audience in 1968. “This, on the face of it, removes me from the pale of the New Left.”

In short, he was a liberal whose moral convictions influenced the tales he wanted to tell and how he wanted to tell them. But overt stories of social criticism risked raising problems with the sponsors and the network censors. This was a major motivation for the creation of The Twilight Zone: allegories, science fiction, and unusual premises not only allowed complicated moral and political stories to be distilled to a potent purity, but they could liberate Serling from some of the limitations of drama on commercial television. “A Martian,” he noted, “can say things that a Republican or Democrat can’t.”

After initial hesitance, CBS in 1959 welcomed the new weekly series, presumably hoping to capitalize on Serling’s high-toned reputation and on the growing appeal of books like Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1950) and Richard Matheson’s The Shrinking Man (1956), and on such similarly cerebral science-fiction movies as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and Forbidden Planet (1956). Moreover, the network had considerable success with Alfred Hitchcock Presents, which also served up a fairly sophisticated mix of dark irony and suspense. The network was less certain about using Serling, à la Hitchcock, as the face of the show, opening and closing each episode with wry, scripted remarks. Although telegenic in his way, Serling was less recognizable than the rotund director. And he looked nothing like the typically nondescript on-camera host. He looked like a well-tailored young rabbi, upright but hip, delivering droll sermons through clenched teeth in a clipped and alliterative style. CBS hedged its bets, scheduling The Twilight Zone against relatively light competition on late Friday nights, the fringe of primetime.

Mike Wallace was also skeptical. In his interview with Serling — conducted just days before The Twilight Zone premiered — Wallace implied that writing about flying saucers and time machines for the new show was something of a comedown for the man whose incisive character studies, realistic in approach, had become touchstones for quality television. After all, science fiction on television heretofore meant shows like Flash Gordon and Rocky Jones, Space Ranger — kiddie stuff made on the cheap. Serling, Wallace implied, would be turning out “potboilers” now, and laughing all the way to the bank. But Serling was adamant: The Twilight Zone was a “high-quality” anthology series, as “adult” in its way as other TV drama had been.

Shot at MGM, The Twilight Zone employed the talents of several accomplished Hollywood veterans, including the directors Mitchell Leisen, Joseph Newman, and Ida Lupino; the composer Bernard Herrmann, famed for scoring Citizen Kane and various Hitchcock hits; and George Clemens, who would win an Emmy for his cinematography on the series. Actors from across four generations appeared on the show, from respected senior figures like Buster Keaton, Gladys Cooper, and Agnes Moorehead, to character actors like John McGiver and Ed Wynn, to up-and-comers like Burt Reynolds, Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper, William Shatner, Robert Redford, and a young Ron Howard.

Serling himself wrote or co-wrote 92 of the show’s 156 episodes, but not every episode was a gem. Some were “real turkeys,” he admitted, such as “Mr. Dingle, The Strong,” a second-season episode in which a two-headed alien walks into a bar — perhaps an attempt, one of several on Serling’s part, to imitate the writings of Fredric Brown, popular in the Fifties for mixing comedy and science fiction in such offbeat classics as Martians Go Home (1955). But for the most part The Twilight Zone was written “with an eye towards the literacy of the actor and the intelligence of the audience.”

In fact, Minow’s analysis in 1961 now looks unduly pessimistic, or perhaps premature. The Twilight Zone belongs in some ways to a golden age of its own. To be sure, by the late 1950s, the networks were cutting links with New York’s art and theater scene and turning almost exclusively to Big Hollywood for their most popular shows. As a result, the live drama showcases disappeared, along with Omnibus and other up-market offerings. But in retrospect, the growing role of Disney, Warner Brothers, and Universal seems inevitable. The nation’s fifty million television owners (up from around three million when the decade began) wanted programs that were less like off-Broadway productions and more like the movies, with bigger design budgets, higher production standards, and more recognizable faces. Moreover, the networks were discovering that filmed series (like old movies) could rerun on television repeatedly, for years, sold in syndication packages to affiliates across the country and independent stations around the world.

Certainly, most of the popular dramatic serials of the late 1950s and early 1960s were not much noticed by what Serling called the “intellectual diehards.” Instead, those shows were considered middlebrow entertainments assembled to connect advertisers with a mass audience and to give those viewers generally happy endings and fairly static heroes symbolizing bourgeois virtue and civic order. Still, the best of them — including Perry Mason, Naked City, The Defenders, Gunsmoke, Bonanza, even The Untouchables — were artful in their way. They were well-acted, well-directed and often surprisingly well-written, and, like most Hollywood movies, required a certain amount of concentration to be fully enjoyed. During much of the 1960s, the television networks still assumed that most viewers were probably also readers, not of Henry James perhaps, but of Erle Stanley Gardner or Zane Grey. They read bestsellers like The Caine Mutiny, Peyton Place, East of Eden, and On the Beach, as well as the short stories in Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. For such viewers, then, good popular fiction need not be sensational or simplistic, but it did require, even within well-worn genres, compelling characters and reasonably fresh storylines. Viewers would welcome shows that avoided juvenility and that aimed to “say something” in a reasonably intelligent way. “It’s our thinking,” Serling insisted in a short promo film aimed at potential sponsors, “that an audience will always sit still and listen and watch a well-told story.” Besides, as he told Wallace, “I don’t think calling something commercial tags it with a kind of an odious suggestion that it stinks.”

Not surprisingly, the stories on The Twilight Zone are replete with postwar liberal themes. Several of them attack prejudice, which Serling later called “the singular evil of our time” and the one from which “all other evils grow and multiply.” Thus in one of the show’s most memorable episodes, “The Eye of the Beholder,” the victim is a young woman, beautiful by our standards, who lives uneasily in a society where “normal” citizens have large bent mouths and pig-like snouts — a twist cunningly hidden until near the episode’s close. In other episodes, the underdogs are slightly comical types who, in an era of gray flannel suits and organization men, insist on pursuing harmlessly eccentric ways. The title character in the episode “Mr. Bevis” cannot hold a job or pay the rent. He reads Dickens, listens to zither music, and plays street games with the neighborhood children. The modern world has little use for Mr. Bevis, who will never be powerful or rich. Mr. Bevis — like Carol Burnett’s hapless Agnes Grep in the episode “Cavender is Coming” — gets some nudges from a guardian angel, but ultimately chooses to stay true to his misfit self. Without the likes of Mr. Bevis, notes Serling in his intro voiceover, the world might be “a little saner” but “would be a considerably poorer place.”

In the fifth-season episode “The Brain Center at Whipple’s,” something of a remake of Dickens’s Hard Times, the outcasts are factory workers who, in the name of progress, are replaced by “automatic assembly machines” that work nonstop, without complaint, and — as the company’s president happily points out — without the bother of pensions, coffee breaks, or powder rooms. Like much science fiction of the 1950s and 60s, The Twilight Zone looks frequently at the bewildering effects of science and technology, including the “battle between … the brain of man and the product of man’s brain,” as Serling puts it in the episode’s opening. And yet the series largely avoids the easy portrayal of modern machinery as monstrous and threatening; generally, as in “Whipple’s,” technology is dangerous only when it is misused by foolish people who fail to appreciate the power of their tools. Wallace V. Whipple, the antagonist here, is a humorless numbers man who, over the protests of his loyal employees, clearly savors the delicious sense of power that comes from slashing costs and making “the stockholders cheer.” He fires his foreman and chief engineer who, in passionate speeches worthy of Clifford Odets, protest the heartless dismissal of “men who have worked here for twenty to thirty years.” “You can’t pack ’em in cosmoline like surplus tanks!” shouts the foreman. But the sight of the sleek new machines whirring away simply intoxicates Whipple — until he too is replaced by a stout robot (the famous “Robby,” first featured in Forbidden Planet) shown busily ensconced in the executive suite in the final scene. Serling remarks in closing that man too often “becomes clever instead of becoming wise.”

The Twilight Zone is famous for its twist endings — its unexpected inversions and ironic moral lessons. In “The Rip Van Winkle Caper,” a clever scientist and his criminal cohorts steal a fortune in gold bars and then, to escape, enter a series of hidden chambers designed to keep them in a state of suspended animation for a hundred years. When they do emerge, after a century of sleep, they eagerly grab their stashed gold — only to discover that the metal, now industrially produced, has virtually no value.

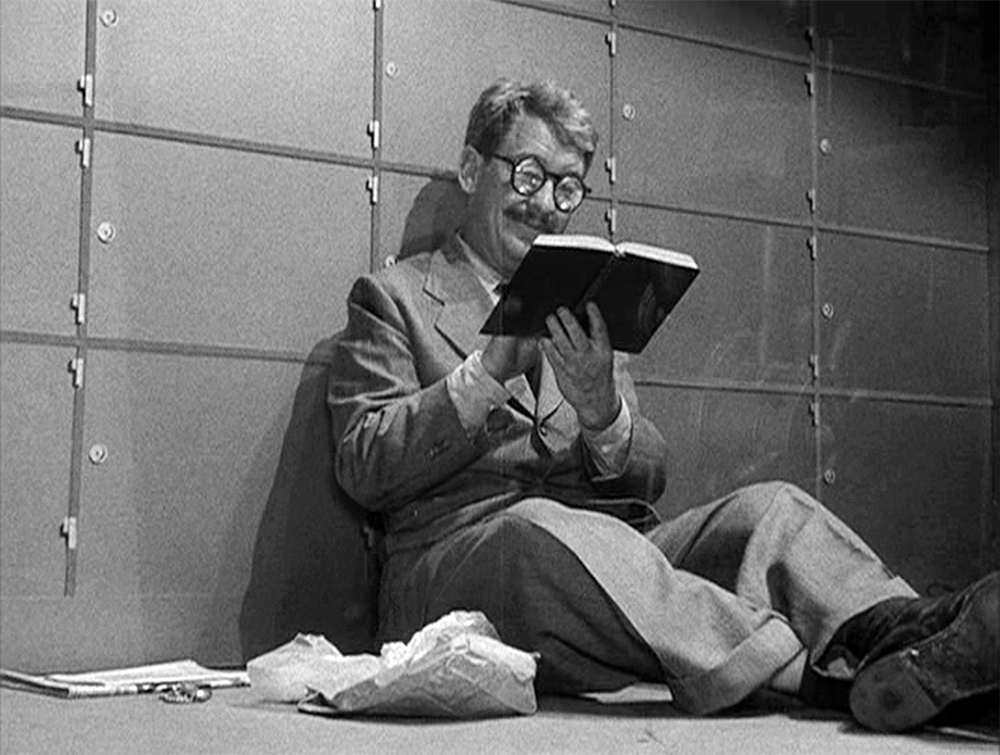

In “Time Enough at Last,” perhaps the most famous Twilight Zone episode, a myopic bank clerk — the bookworm Henry Bemis, played unforgettably by Burgess Meredith — hides from his boss by ducking into the bank’s vault to read in peaceful solitude. A nuclear bomb falls. Bemis survives the blast and finds food enough to last him for years, but his terrible aloneness and boredom in the wreckage lead him to consider suicide. A moment before he pulls the trigger and permanently depopulates the planet, Bemis sees in the rubble what remains of a public library. “Books, books — all the books I’ll need!” he says. He arranges the volumes in stacks, planning a reading schedule that will keep him occupied for years to come. “And the best thing, the very best thing of all, is there’s time now. There’s all the time I need and all the time I want.” But his eyeglasses fall from his face and shatter. “That’s not fair!” he cries, as the camera pans out, leaving him a tragicomic symbol of the blindness of man.

The anxieties of the nuclear age loom large in many other episodes as well. In fact, among popular television programs of the era, only Star Trek (1966–69) made so much use of such apocalyptic themes. When the third-season Twilight Zone episode “The Shelter” begins, some friendly neighbors are shown celebrating the birthday of a local physician. The mood darkens, however, when radio bulletins begin warning of an impending attack by unidentified flying objects. Suddenly, the episode turns into a retelling of Aesop’s fable of the grasshopper and the ant. As the doctor calmly enters the small fallout shelter he built for his family, the neighbors panic: they have no shelters or survival plans of their own. They turn vicious and violent, bludgeoning the door of the doctor’s basement shelter before the threat passes: the “missiles” were merely satellites. The partygoers are ashamed and the doctor is left scarred — aware that his benign notions of human nature must necessarily be revised. He now knows that his jocular friends, just beneath the skin, are little better than a bunch of “naked, wild animals, who put such a price on staying alive that they’ll claw their neighbors to death just for the privilege.” “We were spared a bomb tonight,” declares the doctor, “but I wonder if we weren’t destroyed even without it.”

Suburbanites also run amok in “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street,” an episode still sometimes shown to students in middle school and high school civics classes. The residents of Maple Street convince themselves that space aliens, masquerading as human beings, have been hiding among them in their “tree-lined little world” as a first step toward global rule. Immediately, suspicions fall upon the local oddball, an insomniac often spotted standing alone late at night, staring at the sky. “Let’s not be a mob!” cries one man — but as the paranoia spreads, Maple Street becomes a frenzied war zone, with rocks and bullets flying. Predictably, the episode is often cited as an indictment of McCarthyism during the “Red Scare,” which is now lodged in the popular imagination as a postwar period of unprecedented tribulation and fear. But the episode also recalls, even more explicitly, the mob-driven irrationalities that fueled the rise of Nazism, still fresh in the public mind in the 1950s, and the subject of several other Twilight Zone episodes. The threat of barbarism, Serling repeatedly suggests, never ends; the margin between order and murderous chaos is thin. “For the record,” asserts Serling at the episode’s close, “prejudices can kill, and suspicion can destroy, and a thoughtless frightened search for a scapegoat has a fallout all of its own.”

Other frightening episodes also counter the wide notion that TV in the late Fifties and early Sixties offered little more than singing cowboys and implacably cheerful families. In the famous episode “To Serve Man,” alien beings — towering, seemingly courteous “Kanamits” — arrive from a far-off planet promoting peace, even as they scheme to harvest gullible humans for food. In “People Are Alike All Over,” an astronaut crash-lands on Mars, where seemingly hospitable residents — looking handsome and fit in their tunics and sandals — promptly lock him up in a Martian zoo, an amusing specimen of an inferior species. In “The Midnight Sun,” the earth drifts from its orbit and, apparently, heads directly toward the sun, leaving its hapless inhabitants to sweat buckets as the planet sizzles and boils. But often, The Twilight Zone portrays a cold world — a world in which hopes and illusions are crushed, and big-talking but “flimsy” earthlings, with their “tiny, groping fingers,” and “undeveloped” brains (as Serling puts it in “People Are Alike All Over”) fall prey to merciless forces beyond their control.

And yet, other equally memorable episodes are less far-fetched and bleak; some portray a more familiar world that is only slightly askew. Some such episodes are morality tales with effective film noir touches — shadowy streets, slick tricksters, desperate men facing down their deepest fears. In “Nick of Time,” written by Richard Matheson, a newly married couple find themselves stuck in a small Midwestern town after their car breaks down. Killing time in a local diner, the husband — a young William Shatner — becomes obsessed with “The Mystic Seer,” a weird little table-top machine that purports to answer profound questions for the price of a coin. Its brief assertions, dispensed on slips of paper — “What do you think?” “If that’s what you really want” — are mere generalities, but Shatner’s character finds them uncannily accurate, even as the camera cuts frequently to the toy-like devil’s head that bobs atop the device, a sly smile fixed creepily on its rubber face.

Is the Mystic Seer a tool for satanic mischief? Or does its power come entirely from the whims and anxieties swirling about in the husband’s head? Don’t be vain. Don’t be selfish. Don’t hanker after easy riches or eternal youth. Be careful what you wish for. These are recurring themes on Serling’s show. And, be very careful when you find yourself in that “middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition,” for it is this, “the dimension of the imagination,” that is in fact “the twilight zone,” as Serling announces in the intro of some of the show’s seasons — the seductive but precarious province that “lies between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge.” In “Nick of Time,” Shatner’s character finally gets a grip and departs the diner, just as another couple settles in before the Mystic Seer, clutching their coins, looking for answers. This pair, Serling implies in his closing remarks, is doomed — too willing to submit to superstition, too likely to face the future “with a kind of helpless dread.”

Similarly, in Serling’s “A Thing About Machines,” a snooty writer’s elegant home is, it appears, haunted. Bartlett Finchley (character actor Richard Haydn) is “a practicing sophisticate,” who “writes very special and very precious things for gourmet magazines and the like” when he is not kicking his television set and denouncing the “mechanical contrivances” of modern life. At first glance, this episode appears to evoke the critique of consumerism and gadgetry that was almost requisite among American intellectuals during the postwar years. (Max Lerner, to choose just one example among many, complained in 1957 that “America has taken on the aspect of a civilization cluttered with artifacts and filled with the mechanized bric-a-brac of machine living,” part of a soul-killing social tendency toward “uniformity” and “conformism.”)

Serling, though, does not identify with Finchley, whose high-handed contempt for his neighbors and employees is enough to make him dislikable. For Serling, who was quite fond of mechanized bric-a-brac, it is Finchley’s hatred of radios, TV sets, typewriters, and other benign devices that make him absurd and prompt his demise. Finchley is spooked when, suddenly, he begins receiving malicious messages from his household appliances. His telephone orders him to leave the house. He is attacked by his suddenly snake-like electric razor. He is chased about and, it seems, driven to death by his own car. But Finchley, the episode implies, has been destroyed by his own prejudices and fears — by a self-absorbed refusal to live contently with what he sneeringly calls “the miracles of modern science.” He has “succumbed,” suggests Serling in closing, to “a set of delusions.” He is “tormented by an imagination as sharp as his wit and as pointed as his dislikes.”

Joel Engel’s 1989 biography and another by Gordon F. Sander, Serling: The Rise and Twilight of TV’s Last Angry Man (1992), depict Serling’s growing weariness with the workload of The Twilight Zone, his unhappiness with his declining ability to write in a way that satisfied himself or others, and his retreat into drinking and what seems like a kind of depression. Anne Serling in her memoir aims to amend these portraits that suggest her chain-smoking father descended into a bibulous funk as his writing career declined. Instead, she remembers a “gregarious and outgoing” man with boyish enthusiasms who amused her friends and his houseguests with a talent for mimicry, who fitted his vintage roadster with a horn that, when pressed, blared forth the theme from The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Serling’s hopeful and upbeat side is often on display in The Twilight Zone, even in some otherwise dark episodes. The fifth-season episode “In Praise of Pip,” written by Serling, has sentimentality and hope puncturing a noir gloom. It also features one of Serling’s favorite types — the shabby loser “whose life has been as drab and undistinguished as a bundle of dirty clothes.” Max Phillips, a small-time bookie, is devastated by news of his son’s wounding in battle in far-off Vietnam. This episode includes memorable scenes in which Phillips (Jack Klugman, in one of several appearances on the show) finds himself lost within a funhouse mirror maze — a deft nod, one assumes, to Orson Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai (1947). The episode ends with Phillips’s spiritual redemption, his aching awareness that “the ties of flesh are deep and strong,” as Serling sermonizes in his epilogue. “You can find nobility and sacrifice and love wherever you may seek it out: down the block, in the heart, or in the Twilight Zone.”

In general, the quality of the show dropped in its last two years. During the fourth season, the episodes were doubled in length to a full hour — but the stories did not always merit that much time, and the pacing sometimes seemed lethargic, so the half-hour format returned for the fifth season. The writing declined in other ways, too: the characters were less sharply drawn, and various conceits were recycled.

Finally, James Aubrey, the CBS programming chief, wanted the show gone, citing cost overruns as well as mediocre ratings and a chronic inability to attract top sponsors. Aubrey, a sort of anti-Newton Minow, had no patience with critics and intellectuals who insisted that the commercial networks had a moral, cultural — even patriotic — duty to “aim higher, write better, dig deeper,” as Serling had put it back in the 1950s. In 1961 Minow, noting the growing global reach of American TV, had asked:

What will the people of other countries think of us when they see our western bad men and good men punching each other in the jaw in between the shooting? What will the Latin American or African child learn of America from this great communications industry?

Aubrey, whose roots were in advertising, did not brood about such things. Most Americans, he believed, did not watch television selectively, by the program, but by the clock, principally as a means of filling up time. Aubrey did not seek to perplex or edify viewers — just to keep them from switching the channel. His idea of good television was The Beverly Hillbillies, not The Twilight Zone, which he believed too idiosyncratic to sit alongside Petticoat Junction and The Munsters in the network’s enormously profitable schedule. Aubrey declared that he was “sick of it.”

And so was Serling, or so he claimed. Before The Twilight Zone, in his 1959 interview with Wallace, Serling had noted that his temperament and talent were best suited for television, “the medium I understand.” He offered his own psychological interpretation: “I suppose this is an admission of a kind of weakness or at least a sense of insecurity on my part…. I want to stay in the womb.” He never quite managed to leave that womb. For years he had promised to quit TV for more ambitiously literary projects — a novel, perhaps, some feature films, a Broadway play. But he had grown accustomed to weekly television’s pressing deadlines: using a Dictaphone, he could polish off a half-hour script in a single afternoon. Highly strung and easily distracted, he lacked the patience for the sort of extensive revisions that good literary prose demands. (Anne Serling quotes a Twilight Zone producer who recalls that a “ten-minute story conference” was, for her father, “the limit, then he’d go out and get an ice cream soda or shoe shine.”) He also had difficulty stretching out a story to fill the bigger frame of a feature film, and, with the exception of Seven Days in May (1964), about a military coup, his clunky screenplays were either poorly received or never made.

So, not surprisingly, after The Twilight Zone ended its run, Serling kept pitching the networks new ideas for weekly series, including The Loner, a “cerebral Western” about a Civil War veteran ambushed by assorted ethical dilemmas while roaming the plains; CBS picked it up in 1965 but canceled it before the first season was over. In 1970 Serling began hosting The Night Gallery, an uneven Twilight Zone knock-off to which he also sometimes contributed scripts. But the show’s producers apparently saw Serling as something of a relic, and limited his creative role. Serling, in turn, became bored with a series that was increasingly formulaic and trite — “Mannix in a cemetery,” he complained. “Good evening sports fans,” he sarcastically announced at the start of one installment. “In discerning circles I’m known as the Howard Cosell of the crypt.”

Serling was still in his forties, and still insisting (during a disastrous tenure as president of the Television Academy) that TV should see itself as “not just an industry but an art form.” But television had passed him by on its way to becoming “with the single exception of the workplace,” the “dominant force in American life today,” as Jeff Greenfield observed in Television: The First Fifty Years (1977). It was now “our marketplace, our political forum, our playground, and our school.” CBS had become the “single biggest advertising medium in the world,” wrote David Halberstam in The Powers That Be (1979), a fact not lost on the industry’s leaders, who had presumably embraced the maxim, commonly attributed to Aubrey, that TV worked best when it relied on the surefire recipe of “bosoms, broads, and fun.” “We’re a medicine show,” confessed one network official quoted in Greenfield’s book. “We’re here to deliver the audience to the next commercial. So the basic network policy is to set in motion from the beginning of prime time to the end of prime time, programs to maintain and deliver those audiences to the commercial.”

Of course, commercial networks in the 1970s were not, as they are today, almost entirely lowbrow, pitched to high school kids and adults who share their tastes. Certain popular comedies, like The Bob Newhart Show and M*A*S*H, featured smart writing and distinctive characters who, despite their quirks, lived like grown-ups in a recognizable world. Even the hit police drama Kojak provided skilled acting and fairly thoughtful narratives that are still watchable today. But during the 1970s the growth of cable and the rise of PBS, which Newton Minow championed, effectively freed CBS, NBC, and ABC to fight with each other in the high-pressure ratings races without the added burden of catering to more discriminating viewers, who could now be directed to Nova and Masterpiece Theatre instead. Moreover, as Greenfield notes, the shift from black-and-white to color programming meant that “the original attraction of television drama — a close-up look at people in conflict,” was now definitively replaced by “an obsession with action” — explosions, car chases, stock heroes and villains, girl cops in swimsuits punching out bad guys in tropical locales. Not surprisingly, in 1976, just a year after Serling’s death, several of the most popular network shows were, in effect, comic strips — The Six Million Dollar Man, The Bionic Woman, Charlie’s Angels.

Serling attacked these trends, picking up where Minow left off. In lectures and interviews, Serling suggested that TV’s most representative programs were becoming even worse than the cliché-ridden radio and television serials he had mocked in the 1950s for their stale plots “sprinkled with a kiss, a gunshot, a dab of sex, a final curtain clinch.” Engel quotes a luncheon speech in which, among other barbs, Serling called Let’s Make a Deal a “clinical study in avarice and greed” and said The Dating Game featured “thinly veiled sexual fantasies” pitched by airhead contestants to “a trio of trick-or-treat Charlies.” Serling, who had set one particularly harrowing Twilight Zone episode — “Death’s-Head Revisited” — in the Dachau concentration camp, particularly hated Hogan’s Heroes, which featured “the new post-war version of the wartime Nazi: a thick, bumbling fathead whose crime, singularly, is stupidity — nothing more. He’s a kind of lovable, affable, benign Hermann Goering.” In a speech at the Library of Congress, quoted in his daughter’s memoir, Serling said Hogan’s Heroes could appeal only to those “who refuse to let history get in the way of their laughter.” The show was, in short, “a rank diminishment of what was once an era of appalling human suffering.”

And yet, Serling himself waded in the shallow end of the TV pool. He hosted a quiz show called Liar’s Club in 1969 and 1970. At the time he died in 1975 at the age of fifty, he was set to host Keep on Truckin’ — a summer variety show starring “Madame,” a wise-cracking puppet made popular on Hollywood Squares. And then there were the commercials. Engel, whose book is especially vivid in depicting how Serling’s ads and endorsements were both a cause and an effect of his depression and self-doubt, offers a partial list:

In 1968 and 1969, Serling touted an almost unending stream of products, including Crest toothpaste, Laura Scudder potato chips, auto loans at Merchant’s Bank in Indianapolis, B. F. Goodrich radial tires …, Packard Bell color televisions, Westinghouse appliances, Anacin, Samsonite luggage, Volkswagens, Gulf Oil, and Close-Up toothpaste (Serling actually introduced the product to the marketplace). He also got paid for his public service announcements for the National Institute of Mental Health (anti-drug abuse), CARE (for Biafran refugees), Epilepsy Foundation of America, United Crusade, the Des Moines Police Association, and the Save the Children Foundation.

And yet, even as he recorded countless ads, Serling continued to rail against the stupidities of commercial television, as in a 1974 speech to the American Advertising Federation: “You wonder how to put on a meaningful drama that is adult, incisive probing when every fifteen minutes the proceedings are interrupted by twelve dancing rabbits with toilet paper.” He did sometimes apologize for his second career as a commercial pitchman. On at least one occasion, he admitted that “a sizable check was thrust in front of me and I plowed in with no thought to its effect or ramifications.” In certain literary circles, hosting the quiz show and doing all those commercials brought Serling scorn. But it was work; it kept him in the game, and more than paid the bills.

Serling — who, early in his career, overestimated the potential of broadcast television — clearly underestimated the staying power of the show that sustains his name. In 1966 he sold back to CBS his sizable stake in The Twilight Zone, suspecting, apparently, that the show, having run its course, would just gather dust in the network’s vaults. But he did not foresee the age of syndication. From the start the series was a hit in reruns, and it is still shown regularly on broadcast and cable outlets around the world, including on Syfy, which for twenty years has run a Twilight Zone marathon on New Year’s Eve. After its cancellation, the show went on to earn “hundreds of millions” of dollars, as Anne Serling ruefully notes, saying that selling it may have been “the worst mistake of his life.”

He did not live long enough to enjoy the continuing influence of the show James Aubrey loathed. Over the years, The Twilight Zone has inspired board games, a magazine, graphic novels, and two other, albeit less successful, series using the same format and name. A 1983 feature film, Twilight Zone: The Movie, was co-produced and co-directed by Stephen Spielberg, who began his career directing scripts for Night Gallery, and whose first feature, Duel (1971), about a murderous tanker truck in pursuit of a terrified motorist, was written by Richard Matheson and has clear Twilight Zone overtones of its own. Chris Carter, creator of The X-Files, has also acknowledged his debt to The Twilight Zone, and echoes of Serling’s series persist everywhere in contemporary science fiction and film. Thus “The Lonely,” the early Twilight Zone episode in which a man falls in love with an attractive robot, his sole companion on a distant, dusty planet, prefigures Her, the 2013 film by Spike Jonze about a lonely man obsessed with the shrewd and seductive female voice on his computer’s operating system.

One wonders how Serling would fare in today’s very different television environment. The kind of time-filling, lowbrow programming that he decried and Aubrey preferred remains widely popular. But alongside it we now have high-quality scripted series distributed by cable channels and streaming companies — dramas of a scope that the movies cannot hope to match, shows that viewers can binge-watch at home on giant screens, often without any interruptions by the dancing rabbits. At least for the moment and at least for that slice of the television market, Serling’s complaints — about advertising as the “basic weakness of the medium” and about the “interference” by commercial interests in the artistic process — no longer apply. Perhaps Serling, with his wish to use television as a vehicle of artistic expression on pressing moral and political issues, would fit right in. (In this regard, it is worth noting that Ithaca College, where Serling taught classes for several years, has created a Rod Serling Award for Advancing Social Justice Through Popular Media; in 2016, the inaugural award was bestowed on David Simon, whose show The Wire is considered one of the foremost exemplars of our latest golden age of television.)

“A writer’s claim to recognition doesn’t take the passage of time very well,” Serling observed in 1957, adding that the aspiring TV writer should buy a scrapbook since that would be “probably the only way he’ll find permanence in recognition.” The creator of The Twilight Zone would be surprised to know that his show is not just remembered today, is not just studied by academics as an artifact from a bygone era, but is still available and watched and loved for its stories and characters and insights into human nature. Almost nothing is left of Rod Serling’s many commercials, the ads that sunk him in moneyed misery. But The Twilight Zone — the show for which he struggled, the artistic achievement he worried would fade to oblivion — remains.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?