In a studio somewhere, amid the smell of roses and cigarettes, bright air spills in with the breeze from a high and open window — the light is good for skin — and a beautiful young man sits for his picture. Outside, bees talk amongst themselves as they flit between the yellow blossom chains of a laburnum. Inside, the dull throb of London electronic music drowns their voices. And the model, who is not a model exactly, but an “influencer,” and in charge here as artist and subject both, has to shout for the camera so he can see the photographs.

Clicking through the portraits, a smile and a blush of color come to his face, and he pauses. One is chosen. Out comes the aluminum laptop, sleek and blank. The picture is loaded. There is subtle editing to do, filters to be applied like varnish on a painting. Now it is time to share, time to be seen. Done with his upload, the comely form reaches for the iPhone from which it is never apart. A thumb finds and summons the icon before it has been told.

Instagram launched in 2010, some hundred and twenty years after Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The slender novel is a fable of a new Narcissus, of a beautiful young man whose portrait ages and conforms to the life he has lived while his body does not. Dorian Gray, awakened to the magnificence and fleetingness of his own youth by an aesthete’s words and the glory of his picture, breathes a murmured prayer that his soul might be exchanged for a visage and body never older than that singular summer day they were portrayed. By an unknown magic his prayer is answered, and the accidents of his flesh are somehow severed from his essence so that he may live as he likes, physically untouched and unchanged. But this division of body and soul leads Dorian to ethical dissolution. For by the fixed innocence of his appearance, the link between action and consequence is severed.

We run the risk of ethical dissolution, too, for although we cannot sever our essences from our appearances, we can indeed create a distance between them. For this we do not need Dorian Gray’s incantation. We have the witchcraft of social media to answer our own prayers — prayers that we might seem to be whatever self we wish to represent, the truth of ourselves hidden away. These mediating social sites and screens dissociate us inwardly, detaching the self from a performed image. And they dissociate us outwardly, detaching us from others by eliminating physical proximity — allowing us to forget others’ humanity, to remove ourselves from the shared scene in which we are all ethical actors.

These dissociations are not limited to Instagram, of course. The self-presentation, and corollary self-obfuscation, of social media persists across platforms. It is as fundamental to text-based online societies as to those made of images. Add the capacity for anonymity that shapes the Twitter experience of so many and we see the matter even more clearly. The whole game is one of playing a character, embodying a chosen ethos, habituating oneself to certain modes of interaction: troll, shitpost, be funny, be right, do not get Mad Online.

The characters we perform on screens, the scripts we write for ourselves as willful acts of self-creation in the void of the Internet, do not possess the contexts that enable us to act ethically in meatspace. Here, in flesh, I am a singular collection of roles and limits: son, brother, neighbor, co-worker, American, some six-foot-one, about ten pounds heavier than I would like to be, the possessor of eyes that need assistance to function, a sinner saved by grace. All these, along with countless other little realities, chosen and unchosen, make my character and unite an I and its image. Of all those things that I bring to Twitter or another social medium, more are a choice than in almost any other setting. And so that which is projected, my identity and appearance to the world online, can be made distant from the real I, the soul and self that are shaped by what I do in that abstracted space.

Another parable out of Wilde’s Dorian Gray: The ever-youthful Dorian falls in love. An actress at a cheap theater has caught his eye with her portrayals of Shakespeare’s heroines. One night she is Rosalind, the next Portia; first joyful as Beatrice, then sorrowing as Cordelia. The conviction of her acting, the reality she gives to those characters whose circumstances she inhabits, charms Dorian. He woos her. He wins her. Her heart is all his.

And this is her tragedy, for now she is more invested in her own story that those of her characters, and her own setting and scene partner are of greater immediacy to her than her stage and castmates. The play’s given circumstances pale in the light of her own experiences. And so she becomes a terrible actress, dismally bad, for she is conscious that it is fiction, all make-believe and just-pretend, and cannot sustain the passion and exquisite verisimilitude that won her the aesthete’s admiration.

Dorian breaks it off. She is nothing to him now. He loved the artistry of her, the characters she played, the romance of her so-nearly-real unreality. The heart of the really real, naïve, silly girl behind those perfect masks is worth nothing to him, though it was that which gave each mask life. He leaves her with cruel words and little thought. She kills herself. A twinge of regret and Dorian moves on, unchanged.

She was true, true to life and true to love, and put her heart and soul in all her roles. But Dorian’s soul and heart were far from her, in oil on canvas. And the reward of this mediated relationship, of the false, the inauthentic, is safety. The person who has more completely severed the self from presentation will emerge less scathed.

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players.” Shakespeare meant to introduce the drama of normal human life, which has its own plots, acts, and scenes. The line is a good reminder here, for we are all moral actors, and what is true of good acting, of good performance, is true of good action, of the action of people we call good. We have in life been given a character, not make-believe but real, whose behavior should conform to setting and circumstance and script in good-faith response to those who share stage and space with us. In a theater, that is all literal: script, set, and scene partners. Out here in all the world the set is wherever we are, our scene partners those people proximate to us at any given moment. And the script? Love thy neighbor as thyself. And who is a neighbor? One who shows mercy, a Samaritan just passing by, who takes pity on a stranger.

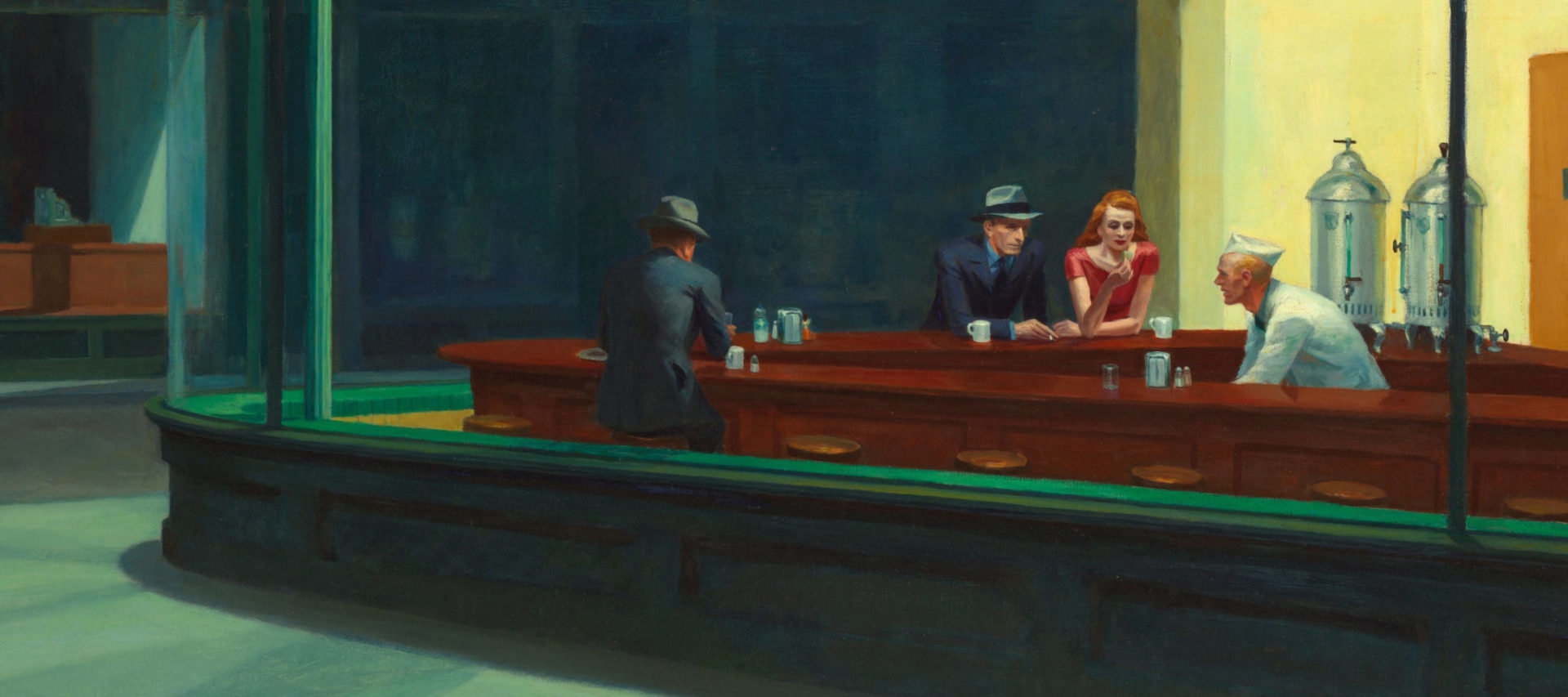

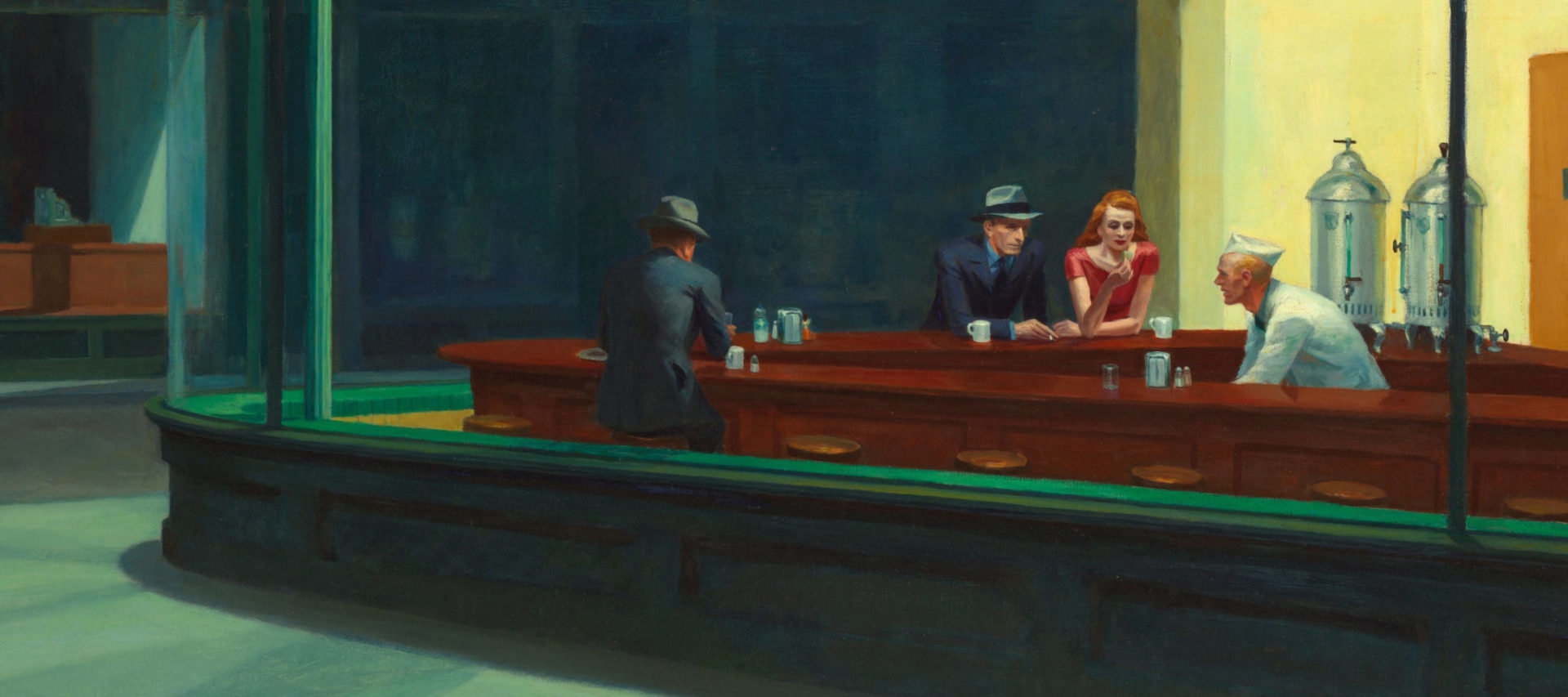

To act well, you must recognize your scene partner. That is usually the person right in front of you. Even that closeness is not enough, of course. We choose often to assign human beings the role of set piece or prop; they are part of the background to our own story, dismissible stage panels and extras — in crowds, on busy sidewalks, crouching at the curb asking us for change. Technology, facilitating instantaneous communication across space, makes that dismissive assignment doubly easier. The self-distancing of social media, like the self-severing of Dorian Gray’s picture, compounds the physical distance, the actual non-proximity of those we interact with. Not only can I be thousands of literal miles from my interlocutor, there is also a digital abyss between me and my self. It all conspires to make it very easy to act badly, to forget myself, to fail to see the other.

Scene.

In a public space surrounded by your fellow man. YOU are all alone together, as has been ever true. Your devices are in your hand, which is new. There is no conversation. Your mind and eyes are on Facebook. All your information, really you, perhaps you think, sits shared there with your friends. A ping sounds. A message tab appears. Your grandfather, PAPA, new to the platform, has sent you a message.

PAPA: hi son, the Facebook says You are “Online”

YOU: hi papa!

PAPA: How are you? It is very cold here, but your aunt got me an electric blanket, so I have been OK.

You do not know what to do with this information.

YOU: oh good

PAPA: Your mother and sister came to see me yesterday. They brought her baby. I got to hold her. She looks just like your sister did when she was little.

Ah, safer ground.

YOU: cool! yeah, she’s really cute

PAPA: When are you going to come home next? Will you visit me?

You live on the other side of the country. His care home smells like dying and mildew. The nurses are strange to you; brusque, tired people who spend their days with geriatric toddlers, feeding them and medicating them and helping them not soil their pants. Some residents are fully returned to the nursery, mewling, all but abandoned; others are merely sad and bored, thumbing through their Bibles and the channels on the television. You find it all unsettling, and feel badly for that.

YOU: I’m coming home for Christmas. I don’t know if we’ll have time to come down to see you. You’ll do Christmas with [A NEARBY UNCLE] and [AN AUNT], right?

PAPA: Yes. You know, you owe me a letter, son.

YOU: oh yeah sorry, I’ve been really busy. [You have not been, not really.] Got to go. Glad your [sic] ok

PAPA: Bye son, I love you. Please keep praying for me.

You close Facebook Messenger and open Instagram, wondering if it isn’t about time you posted again. You know, to remind people you’re there.

Exeunt.

We escape solipsism by knowing the mind of another. We know the mind of another by comprehending its activity and so apprehending its presence. Relating to another’s outward manifestations — hearing his words, watching his facial tics, experiencing his physical presence — we attend to signs of what we are aware of in ourselves, of deliberation, choice, will, and action, and so we recognize a person.

At its worst, social media disrupts this relationship, so that we see not people, but discrete statements, abstracted ideologies, and caricatures. A tweet, comment, post, picture, fave, like, or share is served up as an act of the mind so distinct from anything else that there is no natural, no tacit, comprehensive awareness of the mind behind them. Instead, we — ourselves scattered into so many little bits and bytes — interact not so much with a scene partner as a singular datum. We may say someone is wrong online, but it is not the person we are focused on but her wrongness. There is to you no mind on the other side of the username, or, at least, no mind worth thinking about.

In some sense the heart of social media’s distortive power is that of mass media technology in general: a separation of life’s unity of time and space. We as human beings are that strange phenomenon aware of phenomena, apprehending movement in both halves of spacetime, and that union seems somehow essential to the humane: Chronos, time cold and alone with his sickle and hourglass, is a dread old god. But kairos, the opportune time, the time for actions in space, is propitious and alive in the world.

It is kairos that mass media makes almost impossible to discern, distorting the relationship between speaker and audience, actor and act. We see this in politics, when the rhetoric of those who should govern by deliberation or decision is aimed not at their peers in their chambers but at anxious television spectators far away. In war we sever power and responsibility with drones and missiles and other means of destruction at a distance, so as to minimize the human element in the fight, although it is solely the human that can be ethical. And in the everyday we see it most online, in the whiz of information that seems to just be sitting out there, distributed to such a degree as to be nowhere but now.

Crede, ut intelligas, “believe so that you may understand.” St. Augustine’s account of knowledge as a gift of grace and an act of faith may be our only means of retaining the human, and therefore the ethical, in life online. We must believe and choose to affirm that the other is an other, a mind like ours, a person with a story, a scene partner on this world stage. The charitable graciousness needed for discourse will come no other way, for the systems we have built machinate to scatter and distance us, to prevent the normal means of apprehending a personality and comprehending a person.

We cannot observe, even by credo, the capacities we do not exercise ourselves. Dorian Gray reconciles his life and his image, the severed essence and appearance, by stabbing his portrait and so killing himself. In death his ever-youthful beauty is stripped to reveal a body fit to his soul, “withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage.” Perhaps we can be less drastic, for there are good things the platforms that frame our lives do seem to facilitate, fruitful information and genuine conversation we otherwise might not have. Perhaps the self-portraits we paint online may be preserved if we cut out all that is false in them. If by radical honesty we minimize the dissociation of self and image, if we act truly and well, conscious of all our given circumstances, especially those unchosen, then perhaps we can still use social media as associative forums, still behave in them as ethical characters. But if we cannot, then we should consider our souls, and log off.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?