When Jane Jacobs, author of the 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, outlined the qualities of successful neighborhoods, she included “eyes on the street,” or, as she described this, the “eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street,” including shopkeepers and residents going about their daily routines. Not every neighborhood enjoyed the benefit of this informal sense of community, of course, but it was widely seen to be desirable. What Jacobs understood is that the combined impact of many local people practicing normal levels of awareness in their neighborhoods on any given day is surprisingly effective for community-building, with the added benefit of building trust and deterring crime.

Jacobs’s championing of these “natural proprietors of the street” was a response to a mid-century concern that aggressive city planning would eradicate the vibrant experience of neighborhoods like her own, the Village in New York City. Jacobs famously took on “master planner” Robert Moses after he proposed building an expressway through Lower Manhattan, a scheme that, had it succeeded, would have destroyed Washington Square Park and the Village, and turned neighborhoods around SoHo into highway underpasses. For Jacobs and her fellow citizen activists, the efficiency of the proposed highway was not enough to justify eliminating bustling sidewalks and streets, where people played a crucial role in maintaining the health and order of their communities.

Today, a different form of efficient design is eliminating “eyes on the street” — by replacing them with technological ones. The proliferation of neighborhood surveillance technologies such as Ring cameras and digital neighborhood-watch platforms and apps such as Nextdoor and Citizen have freed us from the constraints of having to be physically present to monitor our homes and streets. Jacobs’s “eyes on the street” are now cameras on many homes, and the everyday interactions between neighbors and strangers are now a network of cameras and platforms that promise to put “neighborhood security in your hands,” as the Ring Neighbors app puts it.

Inside our homes, we monitor ourselves and our family members with equal zeal, making use of video baby monitors, GPS-tracking software for children’s smartphones (or for covert surveillance by a suspicious spouse), and “smart” speakers that are always listening and often recording when they shouldn’t. A new generation of domestic robots, such as Amazon’s Astro, combines several of these features into a roving service-machine always at your beck and call around the house and ever watchful of its security when you are away.

When debates arise over the threat such technologies might pose to privacy, of both their users and the broader public, critics often focus on the power of large technology corporations to control our personal data, as Shoshana Zuboff outlined in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Or they focus on the role of personal security cameras and safety apps in racial profiling and discriminatory policing.

But surveillance clearly provides benefits — and means of abuse — to far more people than Big Tech titans and law enforcement. These are wildly popular technologies among private citizens. We like to look at ourselves and to monitor others, and there are an increasing number of new technologies encouraging us to do just that. This prompts some slightly different questions about the benefits and dangers of surveillance technologies: What kind of people are being formed in a world of everyday surveillance? What assumptions do they make about their neighbors and communities? What expectations do they have for privacy and visibility in their own homes and in their interactions with family members? How can they build relationships of trust without the reassurance surveillance offers of the behavior of others?

In many ways, our enthusiastic embrace of social media ten to twenty years ago softened the ground for our current tolerance for interpersonal surveillance technologies. Who needs a local busybody or town gossip when you have so many people willing to share their most private experiences on X or Instagram — and so many people eager to judge them for it? Social media has long acted as a tool of interpersonal surveillance, even as it has failed to deliver the thriving “digital town square” and healthy communities many of its creators promised.

Interpersonal surveillance technologies offer something equally compelling: A sense of control at a time when many people feel that institutions and systems meant to protect them have broken down. Inside the home, among loved ones, technology-enabled surveillance is becoming the normative form of care: I track you because I love you; I watch you to make sure you are safe. Outside the home, personal surveillance technologies are becoming the unblinking eyes on the street and the neighborhood watch that dispenses with fallible human neighbors in favor of the camera’s unrelenting digital feed.

Beyond their use as practical tools for watching, however, the normalization of these technologies is changing the way we think about ourselves and others as individuals and as members of communities. As much as the ability to monitor each other brings a sense of security, it can also provoke anxiety at being the object of ubiquitous surveillance. Alternatively, becoming comfortable with constant surveillance risks eroding the possibility of trust that has always been, and remains, a pillar of healthy relationships and communities.

It was not that long ago that extensive home security systems were available only to wealthier people who could afford hundreds of dollars for an installation and monthly monitoring fees that security companies charged. Today, fifty dollars will get you a doorbell camera and a de facto home security system. Ring doorbells come with the Always Home app, and Amazon’s Astro household robot with a 30-day free trial of the “Ring Protect Pro” home monitoring service as well as the Astro app, which offers the ability to “see a live view of your home and check in on specific rooms, people, or things” at any time from anywhere.

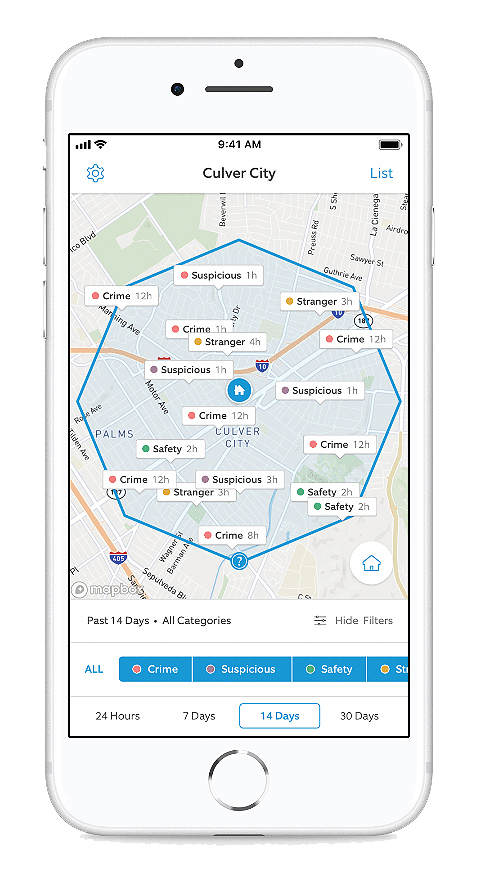

Linked to these tools are apps such as Ring’s Neighbors, which allows users to share information within their neighborhoods and with law enforcement about goings-on and possible crimes in their communities. So, too, smartphone apps such as Citizen market reassurance to users by tracking and reporting local crime. Platforms like Nextdoor provide opportunities for another layer of community surveillance. In 2022, the company had 40 million total weekly active users on the platform, many of whom use it to engage in everyday surveillance of their neighbors’ behavior — with the requisite public shaming of anyone who does not conform to expectations. (The number of posts devoted to dog owners who don’t pick up after their pets or to neighbors who fail to deal with their trash boggles the mind.)

Inside the home, children’s toys make use of “smart” or AI technology to record children’s voices and facial expressions, which toy companies may then use for marketing purposes. In May of 2023, the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice charged Amazon with violating children’s privacy by failing to allow parents to delete children’s voice recordings on its Alexa services and Echo speakers as well as having illegally collected geolocation data about children. Hackers have also discovered how to infiltrate smart speakers and baby monitors. A Mississippi family in 2019 discovered this in the most chilling way possible, when a hacker tormented their child through the Ring camera they had installed in her room, saying, “You can do whatever you want right now…. I’m your best friend. I’m Santa Claus!”

These domestic surveillance technologies, particularly those marketed for home convenience and security, tend to stress safety and control above all. “Where people protect each other,” “Connect and stay safe,” and “Making your world a safer place” are all slogans used by the Citizen app. “Protect your world” is another, and the use of “your” is intentional. These platforms and technologies encourage a surveillance mindset that focuses on the safety and wellbeing of your world, as opposed to the larger world we all inhabit, without considering the challenges that arise when people privatize safety in this way, drawing and policing the boundaries of “us” and “them” in their neighborhoods in ways that might clash with previously informal social boundaries and community expectations. Before Nextdoor existed, you might see a stranger in your neighborhood and assume he’s someone’s guest or a local workman come to fix something. If you were worried, you would call a neighbor to find out who he is. With Nextdoor, your natural reflex is to take his picture and post it to the platform — and perhaps alert the police in the process that someone suspicious has been seen in your area.

In 2018, when it was first launched, the Ring company’s Neighbors platform marketed itself as the “new neighborhood watch,” and safety was its main selling point: the app would gather “your neighbors, the Ring News team and local law enforcement, so we can work together to stop burglaries, prevent package theft and make our communities safer for all.” According to a recent investigation by The Markup, an online journal about technology, more than 2,600 U.S. police departments now have some form of information-sharing partnership with Amazon’s Ring camera network. So do many local government agencies. (On January 24, 2024, as this article was being finalized, Ring announced that it will discontinue a feature allowing law enforcement to request and receive video from users’ doorbell cameras, although other aspects of Ring’s partnership with police appear to still be active.)

In Washington, D.C., where I live, the city’s Private Security Camera Rebate Program offers residents a rebate of up to $500 if they install a Ring-type camera system at their home and register it with the police department. In the past few years, nearly every person on my block has rigged up a front door camera, which many of my neighbors tell me has made them feel safer, even as property and violent crime continue to rise in the city. Although I do not have a camera, my front door and windows are ever visible to my neighbor’s camera across the street, which I find simultaneously reassuring and unnerving.

Similarly, the Citizen app encourages users to broadcast live video from the scenes of emergencies or accidents, turning its customers into informal breaking-news reporters — the “record” button turns red when a user is near an incident. The app, originally named Vigilante, struggled in its early years to define itself as an empowering tool for citizens and an assistant to local law enforcement rather than merely as a platform for digital vigilantism. Reports about users leaving racist comments on crime posts did not help this effort.

But many users of the app have come to embrace the efficiency with which it delivers alerts — often far in advance of official law enforcement alert systems — as well as its “live monitoring” options. In California, Citizen has worked with local organizations to offer discounted live monitoring for at-risk groups. As MIT Technology Review describes, “When it’s dark outside and Josephine Zhao has to walk even a few blocks home in San Francisco, she will sometimes call in an extra set of eyes — literally.” A Citizen agent will monitor not only Zhao’s movements via GPS but can even access her camera and “see what I see” as she walks, she says. It is a technological version of someone walking her safely home.

These technological fixes for broader structural challenges — unsafe streets, property crime, unresponsive law enforcement agencies, lack of meaningful connection with one’s neighbors — bring their own potential risks. There is a reason many of these tools have co-opted the language of community and belonging — citizen, neighbor, next door. These are reassuring terms that evoke what many have lost: a sense of genuine community and belonging.

In this rendering, and in the marketing language of many of these devices and platforms, interpersonal surveillance isn’t problematic; it’s practical. It isn’t the repressive prison panopticon; it’s an adorable Amazon robot. It isn’t the government spying on its citizens; it’s groups of neighbors empowering each other by checking their security camera feeds and reporting suspicious activities.

But even these seemingly helpful effects are not innocuous improvements on old ways of doing things. The “eyes on the street” surveillance of old was physical, often face-to-face, and free from digital watchmen recording every interaction. Today, an increasing number of our interactions are recorded, not just by the state but by each other. This has led to what sociologist Rogers Brubaker calls a “digital enclosure,” analogous to how spaces may be physically enclosed. Spaces that were once publicly unsurveilled are now digitally enclosed, rendering them as data uploaded to platforms over which individuals have little or no control. It is a kind of “platformization,” Brubaker writes, “a movement to enclose more and more of social life within the … embrace of the platform.” Consider how many everyday social spaces are now monitored by livestream digital surveillance — local parks, sidewalks, coffee shops. Many technology critics point out that Big Tech platforms capture and own the data of our everyday lives, often without ever asking our consent, and that this is an unfair invasion of everyday privacy. But we should also be concerned with the way such constant surveillance depersonalizes public space, encouraging the outsourcing of trust to technologies of monitoring in the belief that they are more objective, indefatigable, and thus superior to older, human ways of building trust. The problem of tech surveillance of personal space might be solved by better privacy policies or policymaking. But the problem of tech surveillance of public space creates a much more challenging situation, involving the formation of habits of mind and behavior as we collectively shift our trust of people to trust of the technologies.

The rise of public digital surveillance is both a symptom of and an attempt to address a larger problem: that our own neighbors may be strangers to us. According to a Pew survey in 2018, 57 percent of Americans say they know only some of their neighbors. But among people aged 18 to 29, almost a quarter say they know none, compared to only 4 percent among people over 65. As residents turn to digitized forms of monitoring and surveillance for peace of mind, the root cause — weak neighborhood bonds — is left unaddressed.

Our new tools also habituate us to expect a level of control over others that might undermine the possibility of trust. They can encourage us to engage in new forms of ethical distancing: Viewing the behavior of members of our communities through a Ring camera feed rather than in face-to-face interactions in public space degrades not only our physical interactions but our sense of obligation to others. Healthy communities rely on the people within them to maintain order and offer help when needed. Outsourcing that to machines is an acknowledgement that we have given up on that expectation, even as the convenience of being able to see a package delivered to our doorstep while we’re away brings a sense of control and convenience.

Personal surveillance also poses new challenges to our most intimate relationships. It is not a coincidence that so many of the new domestic interpersonal surveillance technologies are marketed as tools to watch the very young and the very old, populations that require more hands-on human support, who are less autonomous and more vulnerable. Amazon markets its Astro household robot in conjunction with its Alexa Together “remote caregiving service” as “a new way to remotely care for aging loved ones.” Outsourcing the responsibility to keep an eye on others to surveillance-enabled machines brings practical benefits, but also exacts moral costs regarding our duty to care. These surveillance tools often start as surrogates, but quickly become seen as necessary to our busy lifestyles and allow us to justify not taking the time to be with those who need us most.

People habituated to monitoring their intimate behavior and local goings-on, and also fearful for their safety, present new opportunities for the state to embrace more intrusive monitoring: Consider how soft paternalism in public policy — nudging us toward supposedly rational behaviors — combined with newly engrained habits of interpersonal surveillance, might yield people more readily accepting of a state that monitors, for example, household waste disposal or energy use for the larger goal of environmental responsibility. Already accustomed to the “soft surveillance” of their own monitoring and smart technologies, Americans who want to feel both safe and responsible in their daily lives might be willing to accept new levels of state interference at the cost of individual freedom, privacy, and autonomy.

Of course, digital technologies have long posed challenges to our understanding of privacy. Today, the boundary between private and public is thoroughly corrupted. But the scale and scope of our interpersonal surveillance technologies have rendered the debate over individual privacy too narrow, focused almost exclusively on data collection and the fine print spelled out in privacy notices. We should instead talk about the limits of visibility, both public and private. How much visibility to others do we want to accept in our homes and amongst our loved ones, in our neighborhoods and communities? How might the visibility that voluntary surveillance provides reveal things inadvertently about ourselves and our loved ones that we would rather not have others know? How much of what we voluntarily make visible should the state be able to collect and analyze for its purposes?

“Safety on the streets by surveillance and mutual policing of one another sounds grim,” Jane Jacobs wrote, “but in real life it is not grim.”

The safety of the street works best, most casually, and with least frequent taint of hostility or suspicion precisely where people are using and most enjoying the city streets voluntarily and are least conscious, normally, that they are policing.

This was the informal “policing” of a pre-digital age, and it helped shape many neighborhoods and communities in the twentieth century. To be sure, Jacobs’s vision of informal policing suffered from many blind spots regarding race and class, and it would be wrongheaded to idealize that vision. But it was notable in that it included the everyday behavior and experiences of ordinary people in its design.

Today we have new tools and new habits of minds around surveillance that take people out of the equation and replace them with technologies. The short-term rewards are evident — convenience, peace of mind, a feeling of security and control — but the potential long-term dangers are also worth considering. As our neighborhoods and communities become more heavily surveilled, they risk becoming more atomized. When it comes to strangers, who may increasingly include our own neighbors, we change the dictum “trust, but verify” to “record and post to Nextdoor.” Fear and vigilance are not the bedrock of healthy communities.

A world of ubiquitous interpersonal surveillance is one where our homes and families might begin to resemble not the “little platoon we belong to in society,” to borrow from Edmund Burke, but rather the atomized spawn of Jeremy Bentham, who once wrote that “it were to be wished that no such thing as secrecy existed — that every man’s house were made of glass” since “the more men live in public, the more amenable they are to the moral sanction.”

Our houses are not yet made of glass, but our use of interpersonal and private domestic surveillance technologies is slowly rendering them as visible as if they were — at least to the increasing number of people, corporations, and government entities who know how to watch what we so eagerly broadcast. Interpersonal surveillance technologies have rendered us far more visible to each other and given people a sense of security and safety when it comes to protecting their homes and loved ones. But they have not helped rebuild the one thing that human beings need to live together in peace: trust.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?