“Burner of ashes” — there’s a job description one rarely sees these days. Yet going back to the Bronze Age, the ash burner had an essential if dirty job. Soaking wood ashes and water in a pot, then filtering the liquid and boiling it to evaporate all the water yields potash, useful in making dyes, soap, glass, and fertilizer. From burnt wood to fertilizer: out of the ashes comes new life.

Will AI Be Alive?

An essay in three parts

Introduction

1. Gaining Situational Awareness About the Coming Artificial General Intelligence

2. It Will Seem to Be Alive

3. We Must Steward, Not Subjugate Nor Worship It

Just as Smith and Baker are names derived from occupations, so is Ashburner in English and Aschenbrenner in German. The person today who perhaps best lives up to the family name is Leopold Aschenbrenner. A child prodigy who started at Columbia University at the age of fifteen and graduated in 2021 as a nineteen-year-old valedictorian, Aschenbrenner found his way to a job at OpenAI. He was fired in April 2024 — in his telling, for seeking feedback on a safety research document from outside experts, which OpenAI saw as leaking sensitive information.

Aschenbrenner responded to his firing by founding an investment fund for artificial general intelligence (AGI), launched alongside the 165-page “Situational Awareness: The Decade Ahead.” The term “situational awareness” is used in military and business contexts to describe the kind of rich understanding of an environment that allows one to plan effectively and make decisions. Aschenbrenner’s essay series shares his insider situational awareness of where AI is headed, with AGI “strikingly plausible” by 2027 and artificial superintelligence — automated development of AI by AGI — coming hot on its heels.

Silicon sand is turning into new life. Aschenbrenner writes convincingly and with grave concern that the world is not ready for the forces soon to be unleashed.

It is quite possible that he is wrong. Past performance is no guarantee of future results, and what can’t go on forever, won’t. But equally relevant here are the maxims “forewarned is forearmed” and “better safe than sorry.” An unlikely but dangerous outcome may still demand our attention. This is especially the case because Aschenbrenner’s argument that AGI will likely be here soon is so straightforward.

It goes like this. The difference between the scant capabilities of OpenAI’s GPT-2 in 2019 and the astonishing capabilities of GPT-4 in 2023 is five orders of magnitude of effective compute — a measure of a system’s actual computational power, including not only the raw power of its hardware but the efficiency of its software, the level of resource overhead, and so on. On this basis, there are two things we have good reason to expect:

For the effective compute of AI models to increase by another five orders of magnitude in a few years, two big obstacles would have to be overcome: more physical computing power and more efficient algorithms. Let’s consider each in turn.

Continuing the dramatic increase in computational ability of the last few years would require a preposterously large number of dedicated computer chips and using enormously large amounts of electricity. In 2023, Microsoft committed to buy electricity from Helion Energy’s in-the-works nuclear fusion power plant, a company for which OpenAI’s Sam Altman had previously helped raise $500 million; in March 2024, Amazon paid $650 million for a data center conveniently located adjacent to a nuclear power station in Pennsylvania.

Those sums together are well over two orders of magnitude smaller than the $500 billion that OpenAI, Oracle, and two other firms have committed over the next four years to the new Stargate project announced by President Trump only days after he took office this year. For ease of comparison, let’s say that’s $100 billion per year. This is an order of magnitude less than the trillion dollars per year that Aschenbrenner expects would be needed to produce enough computing power for AGI, which would use 20 percent or more of the total amount of electricity currently produced in the United States.

This may seem laughably large, an impossible goal. We are not presently on trend to attain it, that much is clear. In 2024, Goldman Sachs released a report estimating that U.S. power demand will grow only 2.4 percent by the end of the decade, with data centers making up a large part of that demand but AI using only a fifth of the increase. Tech companies are building where the electricity is and the regulators aren’t, planning data centers in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Aschenbrenner would prefer not to see our tech secrets handed over to America’s frenemies, and he both calls for and expects a new Manhattan Project for AGI. Project Stargate, set to be centered in Texas, looks like a step in that direction.

At their peaks, notes Aschenbrenner, the Manhattan and Apollo projects each cost 0.4 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, which would today be about $100 billion — roughly the amount of yearly investment currently committed to Stargate. Is another order of magnitude of funding possible? Probably so. Between the national security importance and the commercial possibilities, a dramatic scale-up in AI investment will likely only be forestalled by something even bigger — a government breakup of Big Tech, a Great Depression, or an act of God like a devastating solar flare, an asteroid, or an earthquake that sends California into the sea.

It’s also worth noting that major advances in quantum computing would make enormous investments in server farms and electricity production unnecessary. In December, Google Quantum AI announced a major breakthrough with its new Willow chip, for the first time scaling up computational power while exponentially reducing the error rate and attaining real-time error correction. And in February, Microsoft went even further with its Majorana 1 chip, which it claims achieves an entirely new state of matter, which in turn allows for creating a new type of qubit, which is a key step toward achieving very low error rates and a practically useable quantum computer. Quantum computers are still far from ready for mass production, but they are now more probable than merely possible.

The second obstacle is making algorithms more efficient. Moore’s Law, describing progress in computer hardware, famously holds that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles about every two years. The research firm Epoch AI has found a similar, though even faster, pattern in the progress of AI software capabilities for both image and language modeling: every eight or nine months, improvements in AI algorithms produce a doubling effect in available compute — by cutting in half the compute required. Many more computer chips and power plants will still be needed, but Aschenbrenner expects software improvements to be just as important as those in hardware. Perhaps they will be even more important, if the success of the DeepSeek-R1 model is not a fluke but rather an indication of what can be accomplished through open source on a limited computing budget.

A common objection to the belief that the trend in algorithmic improvements can continue is that we are running out of unique, quality data. All of these efficient algorithms with high-powered chips have been processing increasingly large training datasets, approaching the size of the entire Internet. But as Aschenbrenner points out, large language models have been doing the equivalent of speed-reading their texts, cramming for an exam the night before and getting ready to spit out answers as quickly as possible when the test comes in the morning. This is part of why LLMs have until recently been bad at math. But better algorithms are still possible using the same datasets.

Programmers are now training LLMs to process texts much more slowly, doing the algorithmic equivalent of carefully working through the practice problems in a math textbook and only then checking the answers, or of talking through a problem with a study-buddy. “In-context learning” allows the LLM to carefully scrutinize a particular subset of data for answering a question.

For example, the endangered language Kalamang on the island of New Guinea has fewer than 200 speakers and almost zero digital footprint, so next to nothing about it was included in Google Gemini 1.5 Pro’s training data. But when Google uploaded a reference grammar and a short dictionary to the LLM’s “context window,” it was able to translate from English to Kalamang as well as human testers could when given the same resources and prompts.

As of yet, there is no way for the LLM to incorporate this in-context learning into its fundamental “weights” or neural network architecture; there is no bridge between short-term and long-term memory. But if and when computer scientists build that bridge, it could lead to the kind of exponential gains that AlphaGo saw from playing the game Go against itself — except that these would be gains in, say, the ability to direct a drone swarm to avoid countermeasures, or the ability to manipulate humans into acting on chatbot advice.

In addition to more physical computing power and more-efficient algorithms, there is a third way in which Aschenbrenner expects AI to advance by orders of magnitude in the coming years. He calls it “unhobbling,” recalling the binding used on horses’ front legs to keep them docile.

In the interest of safety and commercializability, today’s LLMs are substantially hobbled in ways that can easily be undone. For the most part, they are generic chatbots given short prompts and reset after each series of queries. Unhobbling means, for example, customizing the chatbot with detailed information about the history and preferences of the person or company using it. Another example: Publicly available LLMs do not yet have access to the full tools of a computer, let alone a 3D printer. Unhobbling is when AIs are given access to both.

Perhaps the most important issue is what Aschenbrenner calls the “test-time compute overhang.” LLMs break down queries and responses into “tokens,” or fragments of vocabulary and grammar. According to OpenAI, each token covers about four characters, and is the unit for computation and thus for billing by usage. But if software and hardware increases make computation costs go down, then the “compute overhang” can increase, and many more tokens can be used to answer each question.

Most LLMs now sacrifice depth for efficiency, relying on what has been called “System 1”: automatic, intuitive thinking. This is how we get results like ChatGPT insisting that there are two r’s in “strawberry.” But, increasingly, LLMs are being taught to pursue “System 2”: deliberately slow, self-checking chains of reasoning. Currently, the maximum output from a public OpenAI reasoning model (o1) is 100,000 tokens. Using Aschenbrenner’s assumption that a person can think quickly at about 100 tokens per minute, this is equivalent to two normal workdays of very focused work.

Think of a task like “read these seven academic papers, summarize them for me, come up with a new research question based on a synthesis of their findings, and outline a paper that follows up on it,” for which frontier knowledge workers now use AI. But if an AI could use seven figures of tokens per answer in conjunction with the self-play and study-buddy approaches, then it could go from a stream-of-consciousness monologue to drafting, editing, and improving a response so that it represents the equivalent of not two days but a week or a month of one human worker’s effort. This is the path down which Grok 3’s new “think” button, Claude 3.7 Sonnet’s “extended thinking mode,” and similar reasoning functions have taken the first steps.

Speaking of LLMs “thinking” and “reasoning” is where we come to both the deepest objection and the most awful-or-awesome possibility in the trends Aschenbrenner discusses. The objection is that he has implicitly followed a common computer science practice of narrowing down what we mean by “general intelligence” to success on metrics like AP exams, protein-folding problems, and software engineering problems.

This is an important philosophical concern to which we will return. But the practical upshot is that as programmers focus on AI improvements in solving programming problems, and as they succeed in programming successively better artificial programmers that can program themselves, we face what has been called the “intelligence explosion” or, more precisely, a “capability explosion.” If we grant the Machine Intelligence Research Institute’s restrained definition of intelligence as the “ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments,” then we should expect AI programs to look decreasingly like chatbots and increasingly like agents: having agency, the ability to directly affect the real world.

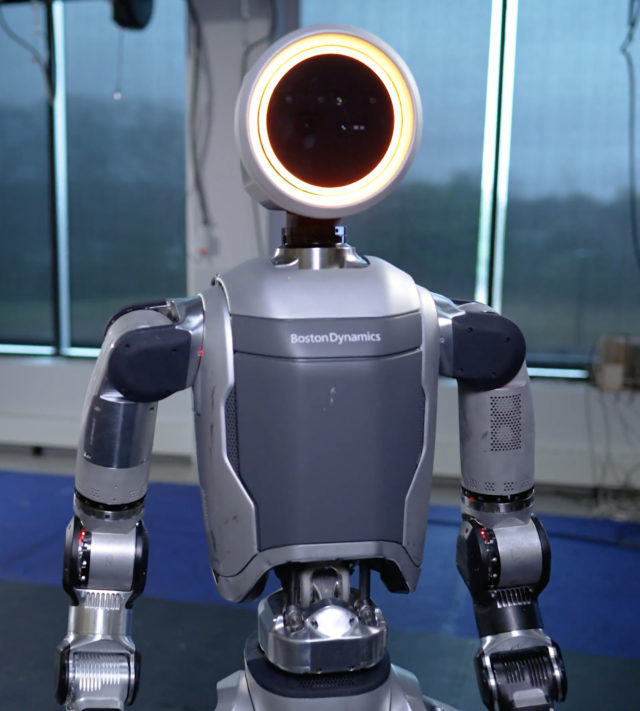

This will be especially clear in the development of AI-powered humanoid robots: Tesla’s Optimus, Boston Dynamics’s Atlas, Figure’s 02, and Sanctuary AI’s Phoenix. In 2011, Marc Andreessen famously wrote that “software is eating the world,” referring to things like Amazon’s victory over Borders. If Aschenbrenner is even close to right, then we haven’t seen anything close to the possible impact of the digital world on the physical.

Silicon Valley’s old motto was “move fast and break things.” Its new one may as well be “move fast and make things.”