A response to “How to Fix Social Media” by Nicholas Carr

In the debate over how or whether to manage social media platforms, we are often presented with a binary: do something; but if that means stifling innovation and breaking the Internet, then do nothing. In such a formulation, there is very little room for self-government.

Nicholas Carr, in an essay that is a welcome contribution to the social media debate, mercifully rejects the binary. In his expertly espoused history of modern radio and telecommunications, Carr examines the perils, pitfalls, and promise the nascent broadcast industry presented — and, critically, the path America took to integrate technological advancements into a democracy, rather than be subject to them.

His exegesis could not come at a better time. Major tech companies like Apple, Amazon, Google, Twitter, and Facebook have tipped the scales toward what Justice John Paul Stevens, then referring to radio broadcasting, called a “uniquely pervasive presence.” These companies now shape public opinion, contorting and restricting the flow of information at a massive scale to suit political or financial incentives. The most powerful corporations the world has ever seen are placing significant costs on the freedom of expression, undermining the values of free speech, diversity of views, and dissent, re-shaping behaviors and interactions along the way.

Tech platforms are also the gatekeepers to major access points of capitalism, with a handful of corporate platforms acting as the mercurial masters of drawbridges to the burgeoning digital economy. These companies harvest our intimate details, provide national security services to the U.S. government, and are the digital backbone of our computing infrastructure. Amazon’s marketplace and web hosting services, Facebook’s ad platform, and Google’s search engine are indispensable tools of business for legions of entrepreneurs. This is also true for upstart and established political campaigns, where the speech and advertising services of Big Tech platforms act as critical infrastructure for political speech and voter engagement.

Ian Bremmer recently argued in Foreign Affairs that social media platforms act more like sovereign states than they do mere private companies, exerting geopolitical influence abroad as well as at home. The platforms, says Bremmer, “will drive the next industrial revolution, determine how countries project economic and military power, shape the future of work, and redefine social contracts.”

Many policymakers, particularly on the right, seem to accept all of this as simply inevitable, as the natural consequence of innovation, which must exist in an ungovernable space for a truly free market to exist. But the key truth of Carr’s illuminating essay is that it is not. The position in which we now find ourselves — with private platforms reformulating the contours of the social order, polarizing our increasingly chaotic political lives while hectoring our free speech traditions and manipulating our markets — is the result of an explicit set of policy choices.

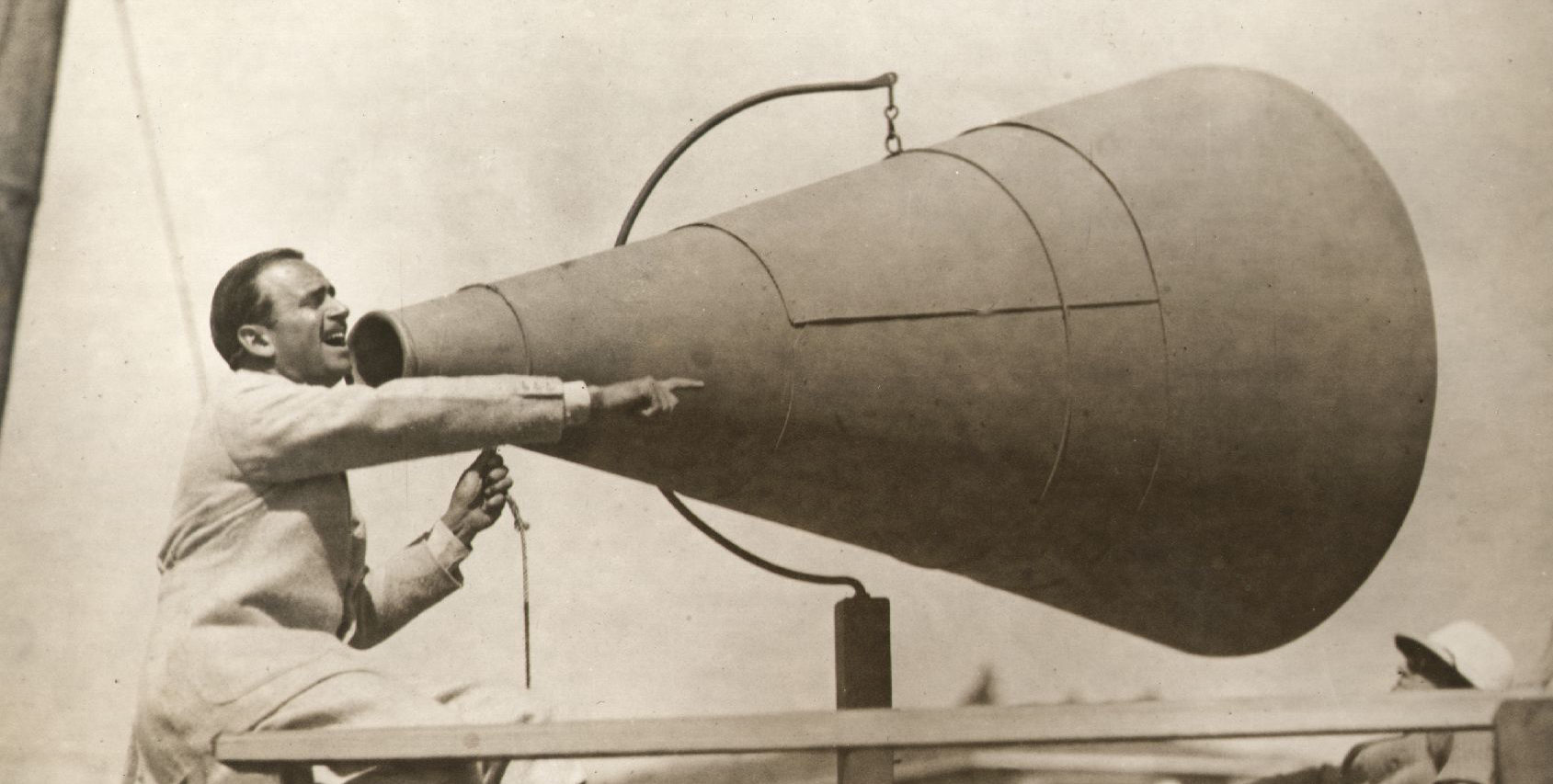

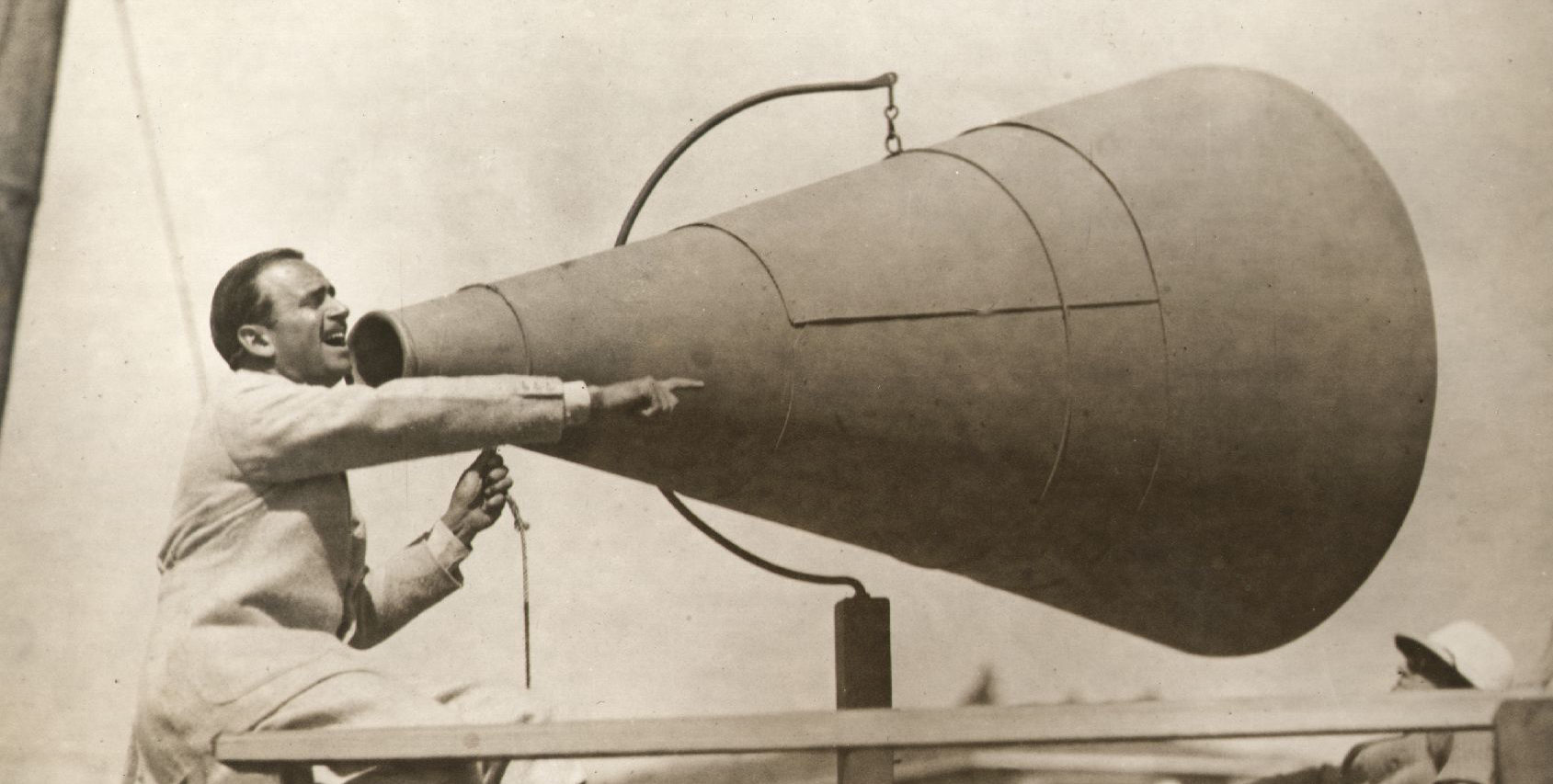

That is precisely what Carr outlines in the case of radio broadcasting, which is less a story of the triumph of so-called permissionless innovation than it is of a democratic society setting the terms for how it will live with technological advances. It is the story of America choosing to govern technologies that radically altered the country, instead of being governed by them.

Our history abounds with examples of similar choices. Carr points to the various telecommunications acts, but there are also the Hepburn Act of 1906, which, among other things, prohibited railroads from transporting commodities in which they had an interest; the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, when Congress chose to democratize the nation’s electric power production; and the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, which restricted banks from entering non-financial business.

Legislatures of the past have had more guts, will, and clarity to see their role as one that, as Carr puts it, “assures the people’s right to have a say in the workings of the institutions and systems that shape their lives — a right fundamental to a true democracy and a just society.”

But the last fifty years or so have been dominated by a neoliberal philosophy that has, in many cases, inverted that calculus, preferring to emphasize the economic benefits to consumers as the only metric worth using, setting aside how these systems interact with the self-determined social consensus and the rights and wishes of citizens.

The emphasis on the consumer, to the exclusion of his consideration as a citizen, has left us with a representative legislature that seems bereft of will and direction. On one side, the left talks about setting up dystopian bureaus of misinformation, while, on the other, the right struggles to overcome rote ideological hurdles about interfering with private industry — neglecting that private industry is subject to thousands of rules and government assistance which many on the right support — and it retains the blinkered belief that the effect of these platforms is merely on one or two sectors, rather than on the economy as a whole.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?

Carr provides some proposals that begin to integrate tech companies into a governable structure: a robust framework for privacy of communication and applying a public interest standard to online broadcasting. To that I would add robust antitrust enforcement, and a more active role for Congress to break the structural dominance of these platforms.

For example, as seventeen state attorneys general recently noted in an antitrust filing against Google, the company owns every side of the market in the most dominant digital ad business in the world — it controls both the buyers and the sellers of ads, and the exchange between the two. According to one senior Google employee cited in the filing, “the analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the [New York Stock Exchange].” Congress should perhaps consider requiring a legal separation of the buy-side and sell-side of the digital ad business.

The looming question behind debates over the major technology platforms is one of sovereignty: Who rules — us or them? It is a question of whether or not we still have the will to govern the products of innovation where necessary, to fit them into our values and traditions, rather than limply accepting a fate that will reform us in their image.

The end of this story is not inevitable. At least, it doesn’t have to be. Our self-government can write another story, to assert itself again on behalf of the people it represents, as it has many times in the past. We simply have to choose to do it.

Notifications