Within the past several weeks, armed protestors have descended upon the Michigan capital as the state’s governor extended a stay-at-home order, and some Texas businesses opened back up early in defiance of the state’s regulations, under the protection of militiamen armed with AR-15s. A short documentary film suggesting that the pandemic was intentionally set in motion went viral, garnering twice as many social media interactions as the Pentagon’s recently released UFO tapes. How did we get here?

In his 2007 book The Honest Broker, political scientist Roger Pielke, Jr. characterized two different idealized styles of decision-making: Tornado Politics and Abortion Politics. In the case of an impending tornado, citizens are bound together by a common purpose: survival. And simply acquiring information — whether through science or direct observation — drives the negotiation about how to respond. In contrast, Abortion Politics is characterized by a plurality of values, and new scientific information only contributes additional complexity to the divergent goals and motivations.

As Pielke admits, this is a somewhat rough characterization. Many contentious issues have elements of both Tornado Politics and Abortion Politics. The conflict over how to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic has been little different. Yet what has been striking is how many people seem to insist that the pandemic be treated as a case of Tornado Politics, as if it were a cyclone bearing down on us. But it hasn’t been this kind of case. Every day, its politics has come more and more to resemble that of abortion, as scientific information about the virus has become weaponized for partisan ends.

Could things have turned out differently? Or were things destined to end up so polarized, so pathological?

When the Chernobyl nuclear power plant blew up on April 26, 1986, the effects were felt far wider than the area around the small Ukrainian town of Pripyat. The explosion sent some radioactive material into the atmosphere, where wind and rain distributed it across Europe. As far away as Norway, thousands of tons of crops were destroyed, and thousands of reindeer killed, because of radioactive contamination. Accounts of former Russian military pilots describe how they were ordered to scatter silver iodide in the atmosphere to make sure Chernobyl clouds precipitated over Belarus rather than Moscow.

The radioactive rain also changed life for sheep farmers in the Cumbria region of northwest England. Government scientists and officials initially dismissed the fallout as negligible, only to suddenly put a ban on the movement and slaughter of sheep in mid-June. Officials assured the worried farmers that the restrictions would be in place for a mere three weeks, after which radiation readings of the sheep were expected to fall to acceptable levels. In the event, restrictions were not completely lifted until 2012, twenty-six years later — a testament to how complex and uncertain radiation science can be.

Restrictions on the ability to earn a livelihood frustrated a great number of the affected sheep farmers. But what made matters worse was the excessive confidence that scientists exuded, and not just about the science of radiation. Scientists simply informed farmers of their assessment, making little effort to convince them of its validity or to consider if they had important knowledge to contribute.

But mistakes began to accumulate. Radiation readings from the local sheep surprisingly increased. The scientists had neglected to notice that local soils were acidic and peaty, unlike the clay soils that were used to derive their models. They also took samples at inappropriate locations, failing to take advantage of farmers’ knowledge of where rainwater accumulated.

Officials further undermined their credibility by making impractical suggestions, such as that farmers should restrict the sheep to the valleys or feed them straw. Government scientists seemed to have never considered asking the farmers themselves to contribute to the discussion over how farming practices could feasibly be altered to diminish the effects of the fallout.

Further souring the relationship between locals and officials was the residents’ troubled history with the nearby Sellafield-Windscale facility, which processed nuclear material. Locals believed that the facility contributed to their cancer rates, not only through more routine radioactive discharges but also due to a fire at the facility in 1957 — an accident that was never adequately researched or resolved to many residents’ satisfaction. Government experts assured farmers in 1986 that Sellafield’s contribution to the radiation levels was minimal, only to be contradicted by a 1988 survey that found the facility’s fire to be responsible for half of the contamination.

Sheep farmers came to distrust the scientists, viewing them, in the words of one account, as “at the beck and call of their government masters.” Experts’ behavior was seen in a new light, as an effort to cover up previously unacknowledged contamination. Because officials insisted on enacting an overconfident form of technocratic politics, repeated failures became perceived as evidence of deliberate deception.

The case of the radioactive Cumbrian sheep illustrates the messiness of the gray area between Tornado and Abortion Politics. We might instead call it Radiation Politics. While it concerns an impending danger, the danger is invisible. No one needs to be a scientist to recognize a tornado approaching, but it is nearly impossible to assess the risks of radiation without expert guidance.

And even then, the science regarding radiation health effects is far from clear. Although the effects are obvious at doses that poison or kill people, scientists remain divided about the harm of low-level radiation. Organizations dedicated to reducing risks, like the Environmental Protection Agency and others that set radiation protection standards, prefer models that are likely to overestimate the harm of low-level exposure. By contrast, industries that use radiation-emitting technologies, such as nuclear medicine and nuclear energy, typically prefer models that presume no harm below a certain threshold of exposure. For many hazards, the process of producing authoritative facts is not at all straightforward. Cases of pure Tornado Politics seem to be very rare.

The inherent uncertainties in the science of impending dangers complicates government officials’ ability to achieve public buy-in. Because empirical evidence is almost always incomplete or not totally convincing, officials must rely on trust, on their own legitimacy. The trouble, as the case of the Cumbrian sheep farmers demonstrates, is that trust is gained in drops but lost in buckets. Storming in to save the day with science is great — until some of the facts turn out wrong. British radiation scientists could have instead worked alongside sheep farmers in finding the pertinent scientific facts, recognizing that the farmers had something to contribute. Instead of expecting the farmers’ deference, this approach would have gone a long way toward earning their trust in the scientists’ own areas of expertise.

Moreover, while Tornado Politics is brief, Radiation Politics can be chronic: a tornado is over within hours, but many Cumbrian sheep farmers had to deal with restrictions for years or decades. Ensuring compliance meant that the restrictions had to “work” for farmers, not totally undermine their livelihoods.

Recognizing the long time horizon for Radiation Politics cements the case for a broader partnership between experts, officials, and the public in such cases, so that solutions are not only evidence-based but also meet people where they are. It is one thing to simply defer to expert authority in the case of a short-lived, clear-and-present danger, but such deference has rarely been sustainable for longer-term challenges. Absent a broader effort to maintain buy-in, some people inevitably begin to wonder if the tornado is really still out there.

The Covid-19 pandemic looks like a case of Radiation Politics. Citizens were told by the surgeon general that masks were not effective at preventing people from catching the coronavirus, only for masks to later become a requirement in many states’ public guidelines. Ventilators were initially seen as essential for coping with the first wave of infections, but now seem to make matters worse for many patients. While early mortality estimates were over three percent, estimates based on the total number of infections rather than diagnosed cases now range between just over one percent to less than a tenth of a percent — and are still hotly disputed. And there was no shortage of assurances back in January that the economic harms would be mild and short-lived.

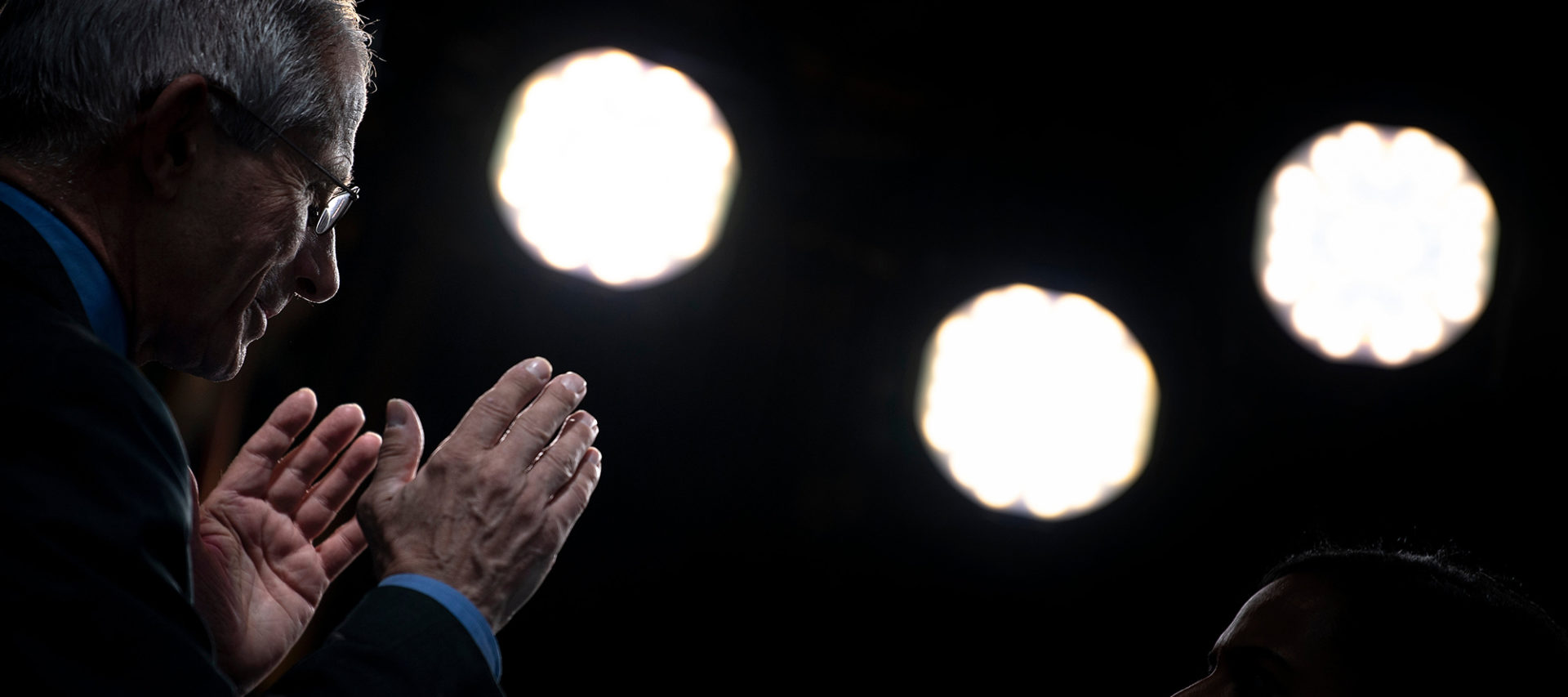

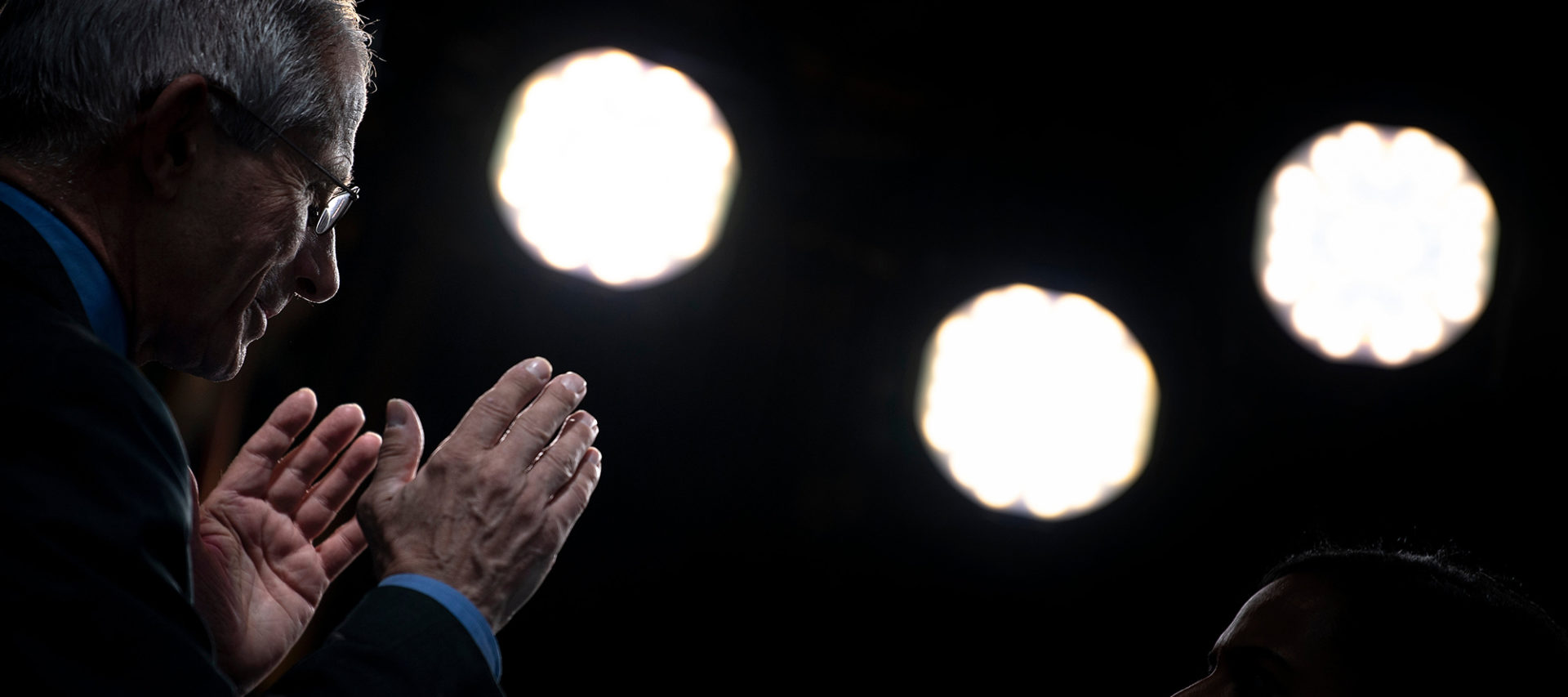

Such reversals are expected as scientists’ understanding of the disease and its effects change with time. That is what science is all about, but precisely for this reason early pronouncements and guidelines did not need to be made so overconfidently. Public health officials became like British radiation scientists in the 1980s. While learning their way through an unprecedented situation, too many government representatives and expert commentators offered arrogant assessments of the risks, even blaming people’s cognitive biases for their panic or their failure to act.

And then there is the World Health Organization’s foot-dragging on declaring a public health emergency and the government’s failure to move fast enough on testing. Mainstream institutions and outlets set themselves up to lose credibility — and even brought more humble and honest experts down with them. No doubt matters were worsened by media outlets and scamsters that profit from sowing more conspiratorial views on public controversies, but that does not absolve officials, experts, and op-ed writers.

Neither were concerns about everyday life and people’s livelihoods sufficiently on the mind of officials. Most governments have seemed oddly caught off guard by the scale of the economic consequences, and by far too many citizens’ increasing reluctance to scrupulously follow official guidelines.

Because Radiation Politics is a long haul, significant consideration must be given to restoring some degree of normalcy. Expecting ordinary citizens to stoically bear whichever socioeconomics conditions seem to most easily appease the epidemiological models is unrealistic — especially in light of a decades-long decline in public trust in government.

But how could have things gone differently? Part of the trouble is that political discourse in general overemphasizes the authority of facts. It is visible in nearly every controversy, where opposing sides lob charges of “pseudoscience” and portray their own preferred experts as the real arbiters of truth. More measured takes are lost in the commotion of overconfident voices.

Placing all our focus on “the facts” falsely suggests that precautionary action requires scientific certainty. People don’t know if their house will burn down, if they will get sick, or if they will suffer a car accident, but they still purchase insurance above and beyond the legal requirement, so long as they can afford it. But our society is not set up for responsibly handling uncertainty. “Authoritative” takes end up getting the most clicks.

An example of a better approach would have been hosting large virtual townhall meetings, or extended deliberative bodies, where officials, experts, and members of the public could have worked alongside one another to examine the evidence and the risks. The public and government representatives could have engaged in a form of mutual fact-finding (as they should have done in Cumbria). Such a process would have clued officials in to missed opportunities. Instead of fighting mask-wearing, they could have recognized that masks, at a minimum, are more likely to help than to hurt. They could have worked toward a reasonable arrangement where citizens were discouraged from buying N95 respirators that were needed for health care workers, but encouraged to buy cloth masks and offered advice on how to use them appropriately.

Greater engagement with the public would have enabled earlier deliberation about how to balance pandemic control goals with people’s livelihoods and lifestyles. The dominance of epidemiological experts and the apparent absence of ordinary people (or even social scientists) led to a response overly focused on infection and death rates, with too little attention on making social distancing and lockdown more tolerable. Regardless of the CDC’s greater knowledge of epidemiology and virology, lay people are the experts when it comes to how to make pandemic controls commensurable with their own well-being. This omission may prove to be the most damaging failure, as many state governments have now swung in the complete opposite direction in response to simmering discontent, hastily moving to “reopen” their economies.

Had officials recognized that Covid-19 was not a case of Tornado Politics, policies to make our society more flexible and amenable to pandemic controls would have been debated months ago. We are just now discussing alternative work schedules like four days on, ten days off, which might ensure self-isolation of anyone infected on the job. Resources could have been more quickly provided to help small businesses build online showrooms and inventories, better setting them up for curbside pickup or delivery. Movie theaters could have been helped with the process of converting into drive-ins, and restaurants with suitably socially-distanced outdoor dining areas. Cities could have geared up to ration access to parks, beaches, and other open spaces, restoring some semblance of normal life.

What matters is not whether these recommendations are the right ones, but that people affected by the shutdown are actually included in the process and workable accommodations and tradeoffs are discovered and implemented. The fanaticism of lockdown resistance is the product not only of a declining trust in official institutions but also of the uncompromising way that pandemic controls were implemented.

But it is not too late. States could still embrace more substantive public engagement and prevent further polarization and distrust.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?