Why do we believe in monsters? With the giant squid and the crocodile, the answer is obvious. These things may lurk and slither in dark water, but they have also made their way into the daylight consensus: They have a place in textbooks and encyclopedias, in the world that respectable people generally agree exists.

With something like Bigfoot, the question is less straightforward. There’s sheer maximalist joy, Adamic thrill, a hope that the world might hold as many things as you can name. There’s the possibility that participation in a chain of discovery might still be open to you. There’s contrarian spite against the arrogance of the world’s Neil deGrasse Tysons.

But finding the reason may not always require going afield. In many cases, people believe in Bigfoot simply because they believe a person who claims to have seen him. A steady family man who spends much of his leisure time hunting in the Pennsylvania woods once related to me an encounter with the legendary hairy creature. He does not tell his story to strangers. He does not even give a definite name to what he saw. Still, listening to him, it’s impossible to think that he’s the type to confabulate, or to misunderstand what he saw.

A credible witness to incredible events can prove surprisingly hard to dismiss. Other types of evidence may be more or less probative, but do not often have the potential to disrupt other parts of one’s everyday epistemic foundation. Testimony is more volatile. Rejecting it often requires you to make significant adjustments in order to square your decision with what you believe. Allowances must be made for the vagaries of memory, alternative explanations offered (however thin). Your relation to the person in question may change. And because the contested grounds take place in the opaque world of another person’s perception, a judgment in either direction involves a leap of faith.

Linda Godfrey’s I Know What I Saw: Modern-Day Encounters With Monsters of New Urban Legend and Ancient Lore is something between a bestiary, a campfire tale collection, and a cryptozoology field report. It is a haphazard survey of extant American monster legends in the tradition of William T. Cox’s 1910 book Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods. But where Fearsome Creatures is a work of imaginative extravagance and linguistic invention (the Tote-Road Shagamaw is my personal favorite), I Know What I Saw grounds an investigative bent in first-person accounts.

Most of the loosely organized sections deal with a broad monster genus — werewolves, mystery cats, Bigfoot, little people — or a more specific local apparition, like the goat-man of Roswell, New Mexico. There’s also generous space given to more typologically ambiguous oddities, like the flying fence-posts of Hillsboro, Wisconsin. But however disparate the subjects, almost every chapter prominently features a first-person sighting, either written, called in, or related in person to Godfrey during her tenure as a semi-professional monster hunter. Her chatty narrative then weaves in parallel accounts, regional folklore, speculation on the alleged creature’s true origins, and, most interestingly, her own attempts to verify local legends with historical research.

We learn about the witchy wolves of Omer, Michigan and the enormous upright dogs that haunt the backroads of Wisconsin. The deer woman of Oglala legend and modern sighting appears on the Dakota plains at night, concealing her cervid legs until a growing sense of unease gives way to terrifying recognition. Those who live to tell the tale do not get out of their cars. A rumored hidden city of hostile little people — in a nice touch of American grotesque, they are by some accounts retired circus performers — has a surprisingly specific address: somewhere near Mystic Drive in Muskego, Wisconsin.

There is no hard distinction between the ancient lore and new urban legend of the book’s subtitle. Creatures that made their debut on the horror-fiction site Creepypasta appear alongside medieval werewolves and Native American Puckwudgies (little people of the forest). The introductory chapter briefly notes the hodge-podge in its discussion of Slenderman, a Creepypasta meme that in 2014 so colonized the imagination of two preteen girls that they stabbed a classmate nineteen times in an effort to propitiate him. According to Godfrey:

Slenderman epitomizes a new, faster day in the spreading of urban legends…. Even a skinny, expressionless meme like “Slendy,” as some bloggers now call him, had to begin somewhere. I believe parts of Slenderman have lurked in the literature, folklore, and traditions of many cultures, and that traces of these other, earlier legends may still be identified in his eerie persona.

The term “meme” — coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene — means a conceptual unit of cultural transmission. A story about a monster, told from one person to another, might be a meme. But something different seems at play in the Slenderman case. The meme is the monster, bursting forth from the shadowy digital realm to wreak havoc in the everyday social world. In fact, the incident spawned a new type of urban legend — one in which various horrifying (and largely fictional) memes are coming for your children.

The Internet does not just intensify the transmission of legend, but engenders new ways in which legend is created, and sometimes acts as the dangerous fairytale forest within which those legends take place. Godfrey’s glancing attention to the role of the Internet is of a piece with her general uninterest in any theoretical taxonomy, or an exhaustive and critical investigation of any single urban legend or rumored cryptid. Her interest is in participating in the transmission process itself: collating a broad selection of accounts, documenting their origins, and exploring the possible connections between them.

Still, it is odd that Godfrey gives the advent of web-created legends such short shrift, given that her work embodies a tension between digital and analog at the heart of contemporary cryptozoology. What we call “cryptozoology” has long been the province of one type of cultural transfer: person-to-person stories, oral traditions within communities. If you heard about a sighting of Sasquatch, it was probably from the person who had seen it (or thought he had), or who knew someone who had seen it. Perhaps you grew up in the rural West, or on a Coast Salish reservation; perhaps you were a hunter or a logger, or knew others who were.

The Internet upended this landscape. Suddenly, people from disparate walks of life, totally unknown to each other, could congregate and build relationships in online fora. Digital connectivity cemented cryptozoology as a discrete subculture by opening it up to anyone who stumbled across it browsing. But it also removed the social context by which you could evaluate another person’s story. That’s one of the delights of online, after all: You can adopt and discard personas at will, and anyone’s story can go viral if it’s good enough.

Perhaps this is why so many amateur cryptozoologists have found a home on YouTube. If personal testimony takes on a different cast in an anonymous forum, a video, in theory, makes an end-run around the social dimension of belief altogether. A video is neutral, objective, precisely because a mechanical or digital recorder has replaced the human eye, and all the inscrutability of perception as an interior process. Two people, seeing a hairy moving hulk in real time, with the usual tricks of slightly different light and standpoint and expectations, may relay wildly different descriptions. But once the image has been captured on camera, everyone looking at the alleged video of Bigfoot can compare and agree on the basics of the video’s content, if not its import. The evidence — and experience — do not depend on any particular social or physical context, and can be neatly packaged, universally accessible, and infinitely shareable.

It was in an emerging cryptozoology subculture that video first figured as a more attractive alternative to the vexing problems of oral testimony. Bigfoot, both as long-standing legend and possible creature, long precedes “Bigfoot” as a cultural phenomenon. The latter — the Bigfoot of refrigerator magnets and throwaway gags and books and conferences and tourist centers — only exists because Bob Gimlin and Roger Patterson allegedly caught him on camera. Likewise, ham radio and programs like Coast to Coast AM prefigured the problem of disembodied oral history on a smaller scale. Given the origins of the craze, it was perhaps inevitable that cryptids would become content. To see is something. To be seen as credible is something. To collect the various prosthetic visions of trail cameras, collate them, add commentary, and create a viral product — that is everything.

MonsterQuest, a History Channel show whose elevator pitch is roughly “cryptozoology as reality TV,” ran from 2007 to 2010, shortly followed by Animal Planet’s Finding Bigfoot and numerous similar imitators. After investigating the “Beast of Bray Road” for a small-town Wisconsin newspaper, and writing a book on the investigation, Linda Godfrey appeared on MonsterQuest as a guest. Since then, she has written over a dozen books and become something of a minor cryptozoological celebrity.

Godfrey’s fame stems from an Internet- and media-driven crypto subculture. And Godfrey herself has lived the dream of the Bigfoot amateur, being supplied with time and budget to head into the woods with a camera, and an audience tuning in for her findings. And yet her latest book is called I Know What I Saw, not Proof of the Wolfman. It’s the people who claim they’ve experienced the destabilizing moment of an unexplained apparition that are the real object of her quest, as much as any cryptid.

It’s when the book becomes too serious about its cryptozoological project that it strains even a generous reading. The sheer variety of legends, and the openness with which Godfrey approaches every account, whatever its red flags, make it hard to take seriously her stabs at stitching together some underlying truth behind them. Often these speculative moments involve somewhat stretched readings of art history or native American stories, in an attempt to prove that a particular sighting or legend is actually an endlessly repeated motif. Extremely unlike or trivially similar stories are assimilated to either a mounting pile of evidence or a kind of universal mythology. Thus, one poor fellow’s account of finding that a flying dogman with a twenty-six foot wingspan had impregnated his dog is somehow related to a Zuni myth of a woman who bears a child by the sun.

But if I Know What I Saw doesn’t do much for cryptozoological or folklorist traditions, there’s something winsome about Godfrey’s open-ended curiosity and willingness to listen to all kinds of people. Her cheerful passion for an outlandish story and investigative zeal belong to a different tradition: good old-fashioned yellow journalism. Godfrey may be a viral-born monster hunter, but she is herself a relict antediluvian. Her background as a small-town reporter makes her interviews with witnesses, her scrolls through microfiche, her travels to haunted sites a ghostly homage to a type of inquiry that now barely exists.

Godfrey’s attempts to track down the origin and confirm the details of local legend are the most interesting and enjoyable parts of the book. One story centers on a Michigan family who in 1865 lost a son at Andersonville Prison, a Confederate camp notorious for its inhumane conditions. When, thirty years later, the soldier’s remains are returned to the family and buried, a she-wolf makes a den on his new gravesite and gives birth to a litter. The townspeople decide that these are no ordinary animals; they are witch-wolves, products of a rumored Confederate curse called “scorbutus,” which puts an evil wolf-spirit into the coffins of returned Union soldiers. In fact, scorbutus is another word for scurvy — a disease that, as Godfrey was able to confirm, really did claim that soldier’s life at Andersonville.

The book’s selling point is MonsterQuest high drama and X-Files ultimate truth, but its heart is a local reporter interested in memory and records, in the teeming microcosms that exist in small library archives and historical annexes. It’s a fascination that needs no larger justification, and the book is at its least ridiculous when it doesn’t try to manufacture one.

Thus, while the book is officially a survey of pan-American legends, it is perhaps best enjoyed as a haunted tour of the Midwest. The heartland of Godfrey’s book is a place of fearful possibilities, of long drives and longer histories, and things farmers see in cornfields under a chokecherry moon. To say it depicts a lurking menace underneath Midwestern nice is to get hold of the stick by the wrong end: Lutefisk and Midwestern nice and witchy wolves are all of a piece, the peculiarities that everywhere inhere and that make every place inerasably itself. As Godfrey puts it:

I have more stories about Wisconsin than other places…. I’ve lived here all my life and have many years of associations to draw upon. More than that, I find that this state is a weirdly inexhaustible microcosm of all the anomalies that are out there. I’ve bloomed where I was planted and found it rich soil. But weird things are everywhere, and I’m constantly asked precisely where.

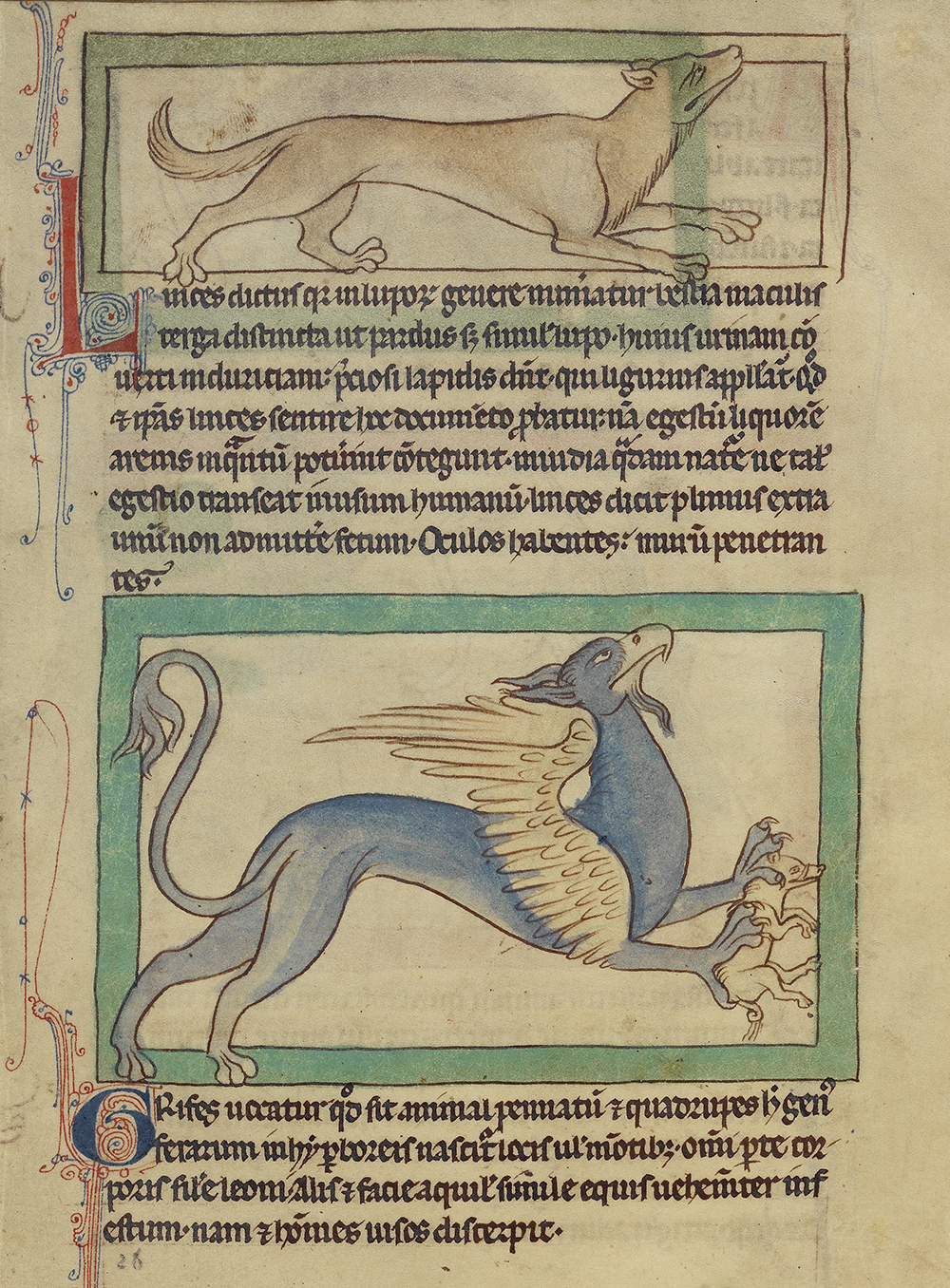

A bestiary is in some ways a curious choice for this type of inquiry. Medieval bestiaries — compendia of critters — were as likely to include the crocodile as the unicorn. Before the world was thoroughly mapped and catalogued, with educated people more or less in agreement about its borders and what they contained, the line between monster and animal was less clear. Bestiaries were social geographies as much as natural histories, with the contours of faraway places often taken whole cloth from ancient authors, or the reports of a few travelers. A seemingly fantastic creature could simply be fauna of an unknown land, and the faraway was in turn tinged inherently with the fantastic. Monsters marked the edge of the map, the place where the known shades into the speculative.

Godfrey’s bestiary carries on the tradition of a catalog of rumor, but its geographic orientation is the opposite: a testament to the “precisely where.” Her monsters do not mark the far edges of the map but the endless varieties of life, confusing and confused, beneath every point on its surface.

In the interim between the two, we have mapped the world in ways that probably exceed the wildest dreams of a medieval geographer. There are the textbooks and the encyclopedias, the globes, atlases, and Wikipedia entries, all creating a general picture; but even before any of that comes into play, a pre-literate child can tune in to the Discovery channel and have something that approximates first-hand knowledge of flora and fauna thousands of miles away. There is no need to mark an outer waste where the known shades into the speculative. Everything already lies open to us, except the boundary between fact and rumor. That has shut.

But it may be that the very thoroughness and speed of our information contain their own deficiencies. We feel that all the world is accessible — and it is, but only in the broad representations that can go into an official, standardized narrative, the textbooks, the encyclopedias, the curated images that make up Discovery Channel specials. The admirable extensiveness of the world’s cataloging can give the illusion that everything is contained within its lines, when in fact, by nature of the enterprise, much is omitted.

A strain of discomfort with what must be excluded in order to create a compendium of settled, universal knowledge has long existed in the paranormal genre. For instance, Charles Fort’s 1919 The Book of the Damned refers not to literal demons, but to inexplicable phenomena collected from newspapers over the years. Fort was not mounting a defense of parapsychology or miracles or spiritualism: It was precisely the failure to support or the inability to fit any explanatory schemas (including supernatural) that interested him. “The damned” is what’s excluded, pushed out of mind and out of sight because it falls between binaries, or fails to comport with accepted narratives of the world.

“Damnation” occurs not just on the conceptual level but also the perceptual. At eight or nine, I remember sitting on my stoop, watching the street turn orange-gold. The little faux Tudor row homes, the overgrown yards, drooping telephone wires, the steep grade of cracked concrete sidewalks — why did it all look so little like the homes on TV? More than that, the angle of the sky hitting the big electric blue auto-parts store, the way my gaze followed the line of the street and terminated at the corner (someone, anyone, could come around it) — all of it felt alive, pulsing with life, and yet utterly excluded from the representations of life universally seen, accessible to everyone, and therefore official and more real. This is not because I existed in a particularly socially marginal place, but because there was a density to a moment in space and time, and all the forms of life crowded inside it simply didn’t translate to the forms of media in which I found a competing “real.”

The dynamics that make video an attractive medium for crypto-evangelists are the same that produced the uncanny comparison between the world-as-seen-on-TV and the world-as-seen-from-stoop. A world of recorded images externalizes the experience of perception. The messiness of an encounter with the endlessly complex world, where boundaries are always dissolving and reconstituting in real time, is transferred to a medium where it can be foreclosed and defined, frame by frame, pixel by pixel. And the interactions of a particular psyche with the world disappear as camera severs eye from mind. The result is something maximally accessible, but without the depth of situated knowledge.

“I know what I saw,” the cri de coeur of Godfrey’s subjects, is a claim on situated knowledge. It’s to say that you are the kind of person who knows the things you look at. When we believe the park ranger who can’t explain the hairy man he once glimpsed, we are in part making a judgment about social status and credibility. But mostly, we trust the park ranger as someone who has spent time and attention staring into dense forest thickets, and who can be trusted to distinguish them from their alleged anomalies. Unlike a camera’s lens, human sight is formed by what it sees. Knowledge of the whole renders the parts visible: Bigfoot emerges from his world, and cannot be reliably known apart from it.

Whether or not Godfrey’s subjects in particular are justified in their claims, “I know what I saw” cannot be displaced by the visual proofs that supposedly get us around belief as an exchange between humans. Nor can “I know what I saw” ever be an appeal to the human eye as a kind of primitive camera, with all the context-free objectivity implied. The human eye can be reliable precisely because it is always attached to a human subject, always involved in a process of perceiving, remembering, imagining, and judging.

The world of small-town journalism from which Godfrey hails was once a bastion of this type of human sight. Like the park ranger, the local journalist spends her time peering into the dense thicket of the raw social — sifting through competing stories, cultivating local sources, listening to gossip, patiently combing through police blotters. It’s a very different type of activity than what will be left when the steady disappearance of local journalism is complete: aggregation, and re-aggregation, opinionating, a global news cycle either endlessly recirculating a few high-level spectacles or composing a hasty narrative out of press releases, social media trends, and perhaps at best a scant few parachuted-in reporters.

Doubtless much of it will be produced by serious media personalities with impeccable résumés, and much of it will continue to provide the epistemic horizon for educated and respectable people. But none of it can effect what local journalism does: the transmutation of the social into the civic — something between the hyper-personal specificity of oral history and the glossy officialdom of scrolling chyrons, thought leadership, and recycled “news of the world.”

Local journalists survey boundary lines and erect landmarks around human life in a place and time. They are part of the mapping process. They say, this place exists because we say it does. Here is what happened. That mapping is always incomplete, and always a product of human sight and human artifice. And at times, like the signs announcing that you are leaving Delaware and entering Pennsylvania, it hovers between the silly and surreal. But the civic, especially in its record-keeping, boundary-drawing forms, has one great advantage: It lets strangers know where they are. It opens up space for those who were not in at the death, or who might not yet be embedded in a web of personal ties or privy to furious dens of partiality. The social feeds the civic, and the civic expands the social. The glossy official is parasitic on both.

There is something melancholy about Godfrey’s transition from reporting to monster-hunting, since both seem poised to devolve entirely into content production. Whether Godfrey is capitalizing on or resisting this devolution is unclear. On one hand, her latest book is full of MonsterQuest nonsense. On the other, her look at her Wisconsin home through the lens of a monstrous bestiary suggests passionate attachment to the local and concrete. The damned and bizarre can capture the particular vividness of a world in a way that resists reducing it to tropes, or over-valuing its reputation in the world of images.

On yet another hand, it is possible to over-explain these things. As anthropologist Colleen E. Boyd puts it, “It is clear to me after years of hearing such stories that people accept sightings and encounters with … spirit beings not as articles of faith but as fact. These things happen and that is why people believe and respond.”

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?