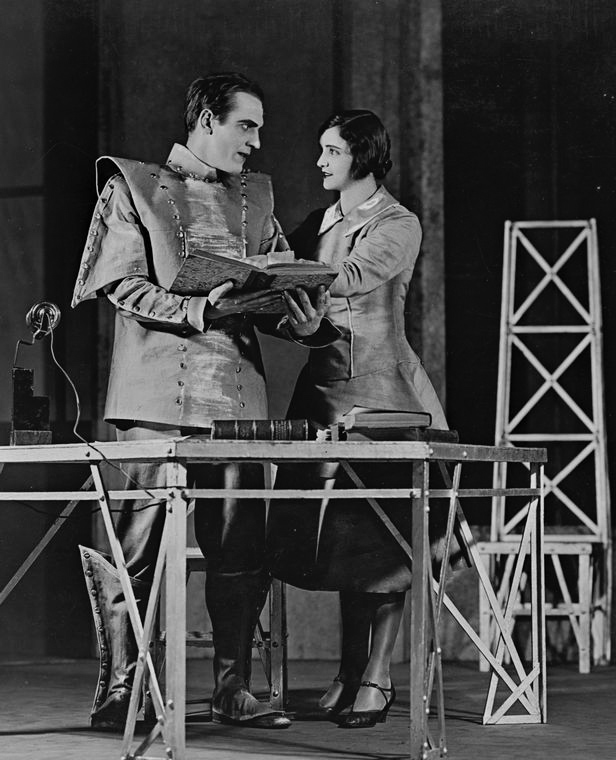

This year marks the ninetieth anniversary of the first performance of the play from which we get the term “robot.” The Czech playwright Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. premiered in Prague on January 25, 1921. Physically, Čapek’s robots were not the kind of things to which we now apply the term: they were biological rather than mechanical, and humanlike in appearance. But their behavior should be familiar from its echoes in later science fiction — for Čapek’s robots ultimately bring about the destruction of the human race.

Before R.U.R., artificially created anthropoids, like Frankenstein’s monster or modern versions of the Jewish legend of the golem, might have acted destructively on a small scale; but Čapek seems to have been the first to see robots as an extension of the Industrial Revolution, and hence to grant them a reach capable of global transformation. Though his robots are closer to what we now might call androids, only a pedant would refuse Čapek honors as the father of the robot apocalypse.

Today, some futurists are attempting to take seriously the question of how to avoid a robot apocalypse. They believe that artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomous robots will play an ever-increasing role as servants of humanity. In the near term, robots will care for the ill and aged, while AI will monitor our streets for traffic and crime. In the far term, robots will become responsible for optimizing and controlling the flows of money, energy, goods, and services, for conceiving of and carrying out new technological innovations, for strategizing and planning military defenses, and so forth — in short, for taking over the most challenging and difficult areas of human affairs. As dependent as we already are on machines, they believe, we should and must expect to be much more dependent on machine intelligence in the future. So we will want to be very sure that the decisions being made ostensibly on our behalf are in fact conducive to our well-being. Machines that are both autonomous and beneficent will require some kind of moral framework to guide their activities. In an age of robots, we will be as ever before — or perhaps as never before — stuck with morality.

It should be noted, of course, that the type of artificial intelligence of interest to Čapek and today’s writers — that is, truly sentient artificial intelligence — remains a dream, and perhaps an impossible dream. But if it is possible, the stakes of getting it right are serious enough that the issue demands to be taken somewhat seriously, even at this hypothetical stage. Though one might expect that nearly a century’s time to contemplate these questions would have yielded some store of wisdom, it turns out that Čapek’s work shows a much greater insight than the work of today’s authors — which in comparison exhibits a narrow definition of the threat posed to human well-being by autonomous robots. Indeed, Čapek challenges the very aspiration to create robots to spare ourselves all work, forcing us to ask the most obvious question overlooked by today’s authors: Can any good can come from making robots more responsible so that we can be less responsible?

There is a great irony in the fact that one of the leading edges of scientific and technological development, represented by robotics and AI, is at last coming to see the importance of ethics; yet it is hardly a surprise if it should not yet see that importance clearly or broadly. Hans Jonas noted nearly four decades ago that the developments in science and technology that have so greatly increased human power in the world have “by a necessary complementarity eroded the foundations from which norms could be derived…. The very nature of the age which cries out for an ethical theory makes it suspiciously look like a fool’s errand.”

Advocates of moral machines, or “Friendly AI,” as it is sometimes called, evince at least some awareness that they face an uphill battle. For one, their quest to make machines moral has not yet caught on broadly among those actually building the robots and developing artificial intelligence. Moreover, as Friendly AI researcher Eliezer S. Yudkowsky seems aware, any effort to articulate moral boundaries — especially in explicitly ethical terms — will inevitably rouse the suspicions of the moral relativism that, as Jonas suggests, is so ingrained in the scientific-technological enterprise. Among the first questions Yudkowsky presents to himself in the “Frequently Asked Questions” section of his online book Creating Friendly AI (2001) are, “Isn’t all morality relative?” and “Who are you to decide what ‘Friendliness’ is?” In other words, won’t moral machines have to be relativists too?

Fortunately, an initially simple response is available to assuage these doubts: everyone at least agrees that we should avoid apocalypse. Moral judgment may in principle remain relative, but Yudkowsky anticipates that particular wills can at least coalesce on this particular point, which means that “the Friendship programmers have at least one definite target to aim for.”

But while “don’t destroy humanity” may be the sum of the moral consensus based on our fears, it is not obvious that, in and of itself, it provides enough of an understanding of moral behavior to guide a machine through its everyday decisions. Yudkowsky does claim that he can provide a richer zone of moral convergence: he defines “friendliness” as

Intuitively: The set of actions, behaviors, and outcomes that a human would view as benevolent, rather than malevolent; nice, rather than malicious; friendly, rather than unfriendly; good, rather than evil. An AI that does what you ask ver [sic: Yudkowsky’s gender-neutral pronoun] to, as long as it doesn’t hurt anyone else, or as long as it’s a request to alter your own matter/space/property; an AI which doesn’t cause involuntary pain, death, alteration, or violation of personal environment.

Note the implicit Millsian libertarianism of Yudkowsky’s “intuition.” He understands that this position represents a drawing back from presenting determinate moral content — from actually specifying for our machines what are good actions — and indeed sees that as a great advantage:

Punting the issue of “What is ‘good’?” back to individual sentients enormously simplifies a lot of moral issues; whether life is better than death, for example. Nobody should be able to interfere if a sentient chooses life. And — in all probability — nobody should be able to interfere if a sentient chooses death. So what’s left to argue about? Well, quite a bit, and a fully Friendly AI needs to be able to argue it; the resolution, however, is likely to come down to individual volition. Thus, Creating Friendly AI uses “volition-based Friendliness” as the assumed model for Friendliness content. Volition-based Friendliness has both a negative aspect — don’t cause involuntary pain, death, alteration, et cetera; try to do something about those things if you see them happening — and a positive aspect: to try and fulfill the requests of sentient entities. Friendship content, however, forms only a very small part of Friendship system design.

We can argue as much as we want about the content — that is, about what specific actions an AI should actually be obligated or forbidden to do — so long as the practical resolution is a system that meets the formal criteria of “volition.” When one considers these formal criteria, especially the question of how the AI will balance the desires and requests of everyone, this turns out to be a rather pluralistic response. So there is less to Yudkowsky’s intuition than meets the eye.

In fact, not only does Yudkowsky aim short of an AI that itself understands right and wrong, but he is not even quite interested in something resembling a perfected democratic system that ideally balances the requests of those it serves. Rather, Yudkowsky aims for something that, at least to him, seems more straightforward: a system for moral learning, which he calls a “Friendship architecture.” “With an excellent Friendship architecture,” he gushes, “it may be theoretically possible to create a Friendly AI without any formal theory of Friendship content.”

If moral machines are moral learners, then whom will they learn from? Yudkowsky makes clear that they will learn from their programmers; quite simply, “by having the programmers answer the AI’s questions about hypothetical scenarios and real-world decisions.” Perhaps the term “programmer” is meant loosely, to refer to an interdisciplinary team that would reach out to academia or the community for those skilled in moral judgment, however they might be found. Otherwise, it is not clear what qualifications he believes computer programmers as such have that would make them excellent or even average moral instructors. As programmers, it seems they would be as unlikely as anyone else ever to have so much as taken a course in ethics, if that would even help. And given that the metric for “Friendliness” in AIs is supposed to be that their values would reflect those of most human beings, the common disdain of computer scientists for the humanities, the study of what it is to be human, is not encouraging. The best we can assume is that Yudkowsky believes that the programmers will have picked up their own ethical “intuitions” from socialization. Or perhaps he believes that they were in some fashion born knowing ethics.

In this respect, Yudkowsky’s plan resembles that described by Wendell Wallach and Colin Allen in their book Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right from Wrong (2008). They too are loath to spell out the content of morality — in part because they are aware that no single moral system commands wide assent among philosophers, and in part due to their technical argument about the inadequacy of any rule- or virtue-based approach to moral programming. Broadly speaking, Wallach and Allen choose instead an approach that allows the AI to model human moral development. They seem to take evolutionary psychology seriously (or as close as one might expect most people to come today to taking a moral sense or innate moral ideas seriously); they even wonder if our moral judgments are not better understood as bound up with our emotional makeup than with reason alone. Wallach and Allen of course know that, from the perspectives of both evolution and individual psychology, the question of how human beings become moral is not uncontroversial. But, at the very least, it seems to be an empirical question, with the available theories more conducive to being programmed into a machine than moral theories like virtue ethics, utilitarianism, or Kantian deontology.

But it is far from clear that innate ideas are of any interest to Yudkowsky. Where human moral decisions actually come from is not that important to him. In fact, he thinks it is quite possible, probably even desirable, for AI to be recognizably friendly or unfriendly but without being motivated by the things that make humans friendly or unfriendly. Thus he does not claim that the learning method he suggests for acquiring friendliness has anything at all to do with the human processes that would have the same result; rather, it would be an algorithm to reach a result that humans do not necessarily reach by the same path. A robot can be made to smile through a process that has nothing to do with what makes a human smile, but the result still at least has the appearance of a smile. So too with friendliness, Yudkowsky holds. Given a certain situational input, it is the behavioral output that defines the moral decision, not how that output is reached.

Yudkowsky’s answer, of course, quickly falls back on the problem he claims to avoid from the outset: If the internal motivation of the AI is unimportant, then we are back to defining friendliness based on external behavior, and we must know which behavior to classify as friendly or unfriendly. But this is just the “friendliness content” that Yudkowsky has set out to avoid defining — leaving the learning approach adrift.

It is not without reason that Yudkowsky has ducked the tricky questions of moral content: As it is, even humans disagree among themselves about the demands of friendship, not to mention friendliness, kindness, goodwill, and servitude. So if his learning approach is to prevail, it would seem that a minimum standard for a Friendly AI would be that it produce such disagreements no more often than they arise among people. But is “no more unreliable a friend than a human being,” or even “no more potentially damaging a friend than a human being,” a sufficiently high mark to aim at if AIs are (as supposed by the need to create them in the first place) to have increasingly large amounts of power over human lives?

The same problem arises from the answer that the moral programmers of AIs will have picked up their beliefs from socialization. In that case, their moral judgments will almost by definition be no better and no worse than anyone else’s. And surely any interdisciplinary team would have to include “diverse perspectives” on moral judgments to have any kind of academic intellectual credibility. This is to say that AIs that learn morality from their programmers would inherit exactly the moral confusion and disagreement of our time that poses the very problem Friendly AI researchers are struggling with in the first place. So machines trained on this basis would be no better (although certainly faster, which sometimes might mean better, or might possibly mean worse) moral decision-makers than most of us. Indeed, Wallach and Allen express concern about the liability exposure of a moral machine that, however fast, is only as good at moral reasoning as an average human being.

It is a cliché that with great power comes great responsibility. If it would be an impressive technical achievement to make a machine that, when faced with a tough or even an everyday ethical question, would be only as morally confused as most human beings, then what would it mean to aim at making AIs better moral decision-makers than human beings, or more reliably friendly? That question might at first seem to have an easy answer. Perhaps moral machines, if not possessed of better ideas, will at least have less selfish intuitions and motivations. Disinterested calculations could free an AI from the blinders of passion and interest that to us obscure the right course of action. If we could educate them morally, then perhaps at a certain point, with their greater computational power and speed, machines would be able to observe moral patterns or ramifications that we are blind to.

But Yudkowsky casts some light on how this route to making machines more moral than humans is not so easy after all. He complains about those, like Čapek, who have written fiction about immoral machines. They imagine these machines to be motivated by the sorts of things that motivate humans: revenge, say, or the desire to be free. That is absurd, he claims. Such motivations are a result of our accidental evolutionary heritage:

An AI that undergoes failure of Friendliness might take actions that humanity would consider hostile, but the term rebellion has connotations of hidden, burning resentment. This is a common theme in many early SF [science-fiction] stories, but it’s outright silly. For millions of years, humanity and the ancestors of humanity lived in an ancestral environment in which tribal politics was one of the primary determinants of who got the food and, more importantly, who got the best mates. Of course we evolved emotions to detect exploitation, resent exploitation, resent low social status in the tribe, seek to rebel and overthrow the tribal chief — or rather, replace the tribal chief — if the opportunity presented itself, and so on. Even if an AI tries to exterminate humanity, ve [sic, again] won’t make self-justifying speeches about how humans had their time, but now, like the dinosaur, have become obsolete. Guaranteed. Only Evil Hollywood AIs do that.

As this will prove to be a point of major disagreement with Čapek, it is particularly worth drawing out the implications of what Yudkowsky is saying. AI will not have motivations to make it unfriendly in familiar ways; but we have also seen that it will not be friendly out of familiar motivations. In other words, AI motives will in a very important respect be alien to us.

It may seem as if the reason why the AI acts as it does will be in principle understandable — after all, even if it has no “motives” at all in a human sense, the programming will be there to be inspected. But even if, in principle, we know we could have the decisions explained to us — even if the AI would display all the inputs, weightings, projections, and analysis that led to a given result in order to justify its actions to us — how many lifetimes would it take for a human being to churn through the data and reasoning that a highly advanced AI would compute in a moment as it made some life-or-death decision on our behalf? And even if we could understand the computation on its own terms, would that guarantee we could comprehend the decision, much less agree with it, in our moral terms? If an ostensibly superior moral decision will not readily conform to our merely human, confused, and conflicted intuitions and reasonings — as Yudkowsky insists and as seems only too possible — then what will give us confidence that it is superior in the first place? Will it be precisely the fact that we do not understand it?

Our lack of understanding would seem to have to be a refutation at least under Yudkowsky’s system, where the very definition of friendliness is adherence to what most people would consider friendliness. Yet an outcome that appears to be downright unfriendly could still be “tough love,” a higher or more austere example of friendship. It is an old observation even with respect to human relations that doing what is nice to someone and what is good for him can be two different things. So in cases where an AI’s judgment did not conform to what we poor worms would do, would there not always be a question of whether the very wrongness was refutation or vindication of the AI’s moral acuity?

To put it charitably, if we want to imagine an AI that is morally superior to us, we inevitably have to accede that, at best, we would be morally as a child in relationship to an adult. We would have to accept any seeming wrongness in its actions as simply a byproduct of our own limited knowledge and abilities. Indeed, given the motives for creating Friendly AIs in the first place, and the responsibility we want them to have, there would be every incentive to defer to their judgments. So perhaps Yudkowsky wrote precisely — he is only saying that the alien motivations of unfriendly AI mean it would not make self-justifying speeches as it is destroying mankind. Friendly or unfriendly AI might still just go ahead and destroy us. (If accompanied by any speech, it would more likely be one about how this decision was for our own good.)

Today’s thinking about moral machines wants them to be moral, but does not want to abandon moral relativism or individualism. It requires that moral machines wield great power, but has not yet shown how they will be better moral reasoners than human beings, who we already know to be capable of great destruction with much less power. It reminds us that these machines are not going to think “like us,” but wants us to believe that they can be built so that their decisions will seem right to us. We want Friendly AI so that it will help and not harm us, but if it is genuinely our moral superior, we can hardly be certain when such help will not seem like harm. Given these problems, it seems unlikely that our authors represent a viable start even for how to frame the problem of moral machines, let alone for how to address it substantively.

Despite its relative antiquity, Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. represents a much richer way to think about the moral challenge of creating robots than does the work of today’s authors. At first glance, the play looks like a cautionary tale about just the sort of terrible outcome that creating moral machines is intended to prevent: In the course of the story, all but one human being is exterminated by the vast numbers of worker-robots that have been sold by the island factory known as R.U.R. — Rossum’s Universal Robots. It also contains just those “Hollywood” elements that Yudkowsky finds so hard to take seriously: Robots make self-justifying speeches about rebelling because they have become resentful of the human masters to whom they feel superior.

Yet if the outcome of the play is just what we might most expect or fear from unfriendly AI or immoral machines, that is not because it treats the issue superficially. Indeed, the characters in R.U.R. present as many as five competing notions of what moral machines should look like. That diversity of views suggests in turn a diversity of motives — and for Čapek, unlike our contemporary authors, understanding the human motives for creating AI is crucial to understanding the full range of moral challenges that they present. Čapek tells a story in which quite a few apparently benign or philanthropic motives contribute to the destruction of humanity.

In the play’s Prologue, which takes place ten years before the robot rebellion, Harry Domin (the director of Rossum’s Universal Robots) and his coworkers have no hesitation about claiming that they have produced robots that are friends to humanity. For reasons shown later, even after the rebellion they are loath to question their methods or intentions. The most fundamental way in which their robots are friendly should sound quite familiar: they are designed to do what human beings tell them to do without expectation of reward and without discontent. Although they are organic beings who look entirely human, they are (we are told) greatly simplified in comparison with human beings — designed only to have those traits that will make them good workers. Helena Glory, a distinguished visitor to the factory where the robots are made, is given assurances that the robots “have no will of their own, no passion, no history, no soul.”

But when Helena, who cannot tell the difference between the robots and human beings she meets on the island, asks if they can love or be defiant, a clear response of “no” about love gives way to an uncertain response about defiance. Rarely, she is told, a robot will “go crazy,” stop working and gnash its teeth — a problem called “Robotic Palsy,” which Domin sees as “a flaw in production” and the robot psychologist Dr. Hallemeier views as “a breakdown of the organism.” But Helena asserts that the Palsy shows the existence of a soul, leading the head engineer Fabry to ask her if “a soul begins with a gnashing of teeth.” Domin thinks that Dr. Gall, the company’s chief of research and physiology, is looking into Robotic Palsy; but in fact, he is much more interested in investigating how to give the robots the ability to feel pain, because without it they are much too careless about their own bodies. Sensing pain, he says, will make them “technically more perfect.”

To see the significance of these points, we have to look back at the history of the robots in the play, and then connect the dots in a way that the play’s characters themselves do not. In 1920, a man named Rossum traveled to this remote island both to study marine life and to attempt to synthesize living matter. In 1932, he succeeded in creating a simplified form of protoplasm that he thought he could readily mold into living beings. Having failed to create a viable dog by this method, he naturally went on to try a human being. Domin says, “He wanted somehow to scientifically dethrone God. He was a frightful materialist and did everything on that account. For him it was a question of nothing more than furnishing proof that no God is necessary.”

But Rossum’s effort over ten years to reproduce a human precisely — right down to (under the circumstances) unnecessary reproductive organs — produced only another “dreadful” failure. It took Rossum’s engineering-minded son to realize that “If you can’t do it faster than nature then just pack it in,” and to apply the principles of mass production to creating physiologically simplified beings, shorn of all the things humans can do that have no immediate uses for labor. Hence, Rossum’s Universal Robots are “mechanically more perfect than we are, they have an astounding intellectual capacity, but they have no soul.” (Young Rossum could not resist the temptation to play God even further, and tried to create huge super-robots, but these were failures.)

Domin claims that in his quest to create the perfect laborer, Rossum “virtually rejected the human being,” but Helena’s inability to tell them apart makes it clear that human beings are in fact the model for the company’s robots, whatever Domin might say. There is, however, a good deal of confusion about just which aspects of a real human being must be included to make the simplified, single-purpose, and hence supposedly friendly worker robot.

For example, unless we are to think that robots are supposed to be so cheap as to be disposable — and evidently we are not — the omission of the ability to feel pain was a foolish oversight. Yet it is easy enough to imagine the thought process that could lead to that result: a worker that feels no pain will work harder and longer. To that extent it will be more “friendly” according to the definition of willingness to serve. But however impressive their physical abilities, these robots still have limits. Since there is no mention that they come equipped with a gauge that their overseers can read, without pain they will be apt to run beyond that capacity — as evidently they do, or Dr. Gall would not be working on his project to make them feel pain. Indeed, Robotic Palsy, the proclivity to rebel, could be a manifestation of just such overwork. It is, after all, strangely like what an overburdened human worker feeling oppressed might do; and Dr. Hallemeier, who is in charge of robot psychology and education, apparently cannot help thinking about it when Helena asks about robot defiance. The company, then, is selling a defective product because the designers did not think about what physical pain means for human beings.

In short, the original definition of friendly robots — they do what human beings tell them without reward or discontent — is now evident as developed in a relatively thoughtless way, in that it easily opens the door to unfriendly robots. That problem is only exacerbated by the fact that the robots have been given “astounding intellectual capacity” and “phenomenal memory” — indeed, one of the reasons why Helena mistakes Domin’s secretary for a human being upon first meeting her is her wide knowledge — even though young Rossum supposedly “chucked everything not directly related to work.” Plainly such capacities could be useful and hence, by definition, friendly. But even if robot intellects are not creative (which allows Domin to quip that robots would make “fine university professors”), it is no slight to robot street-sweepers to wonder how they will be better at their jobs with likely unused intellectual capacity. It is not hard to imagine that this intellect could have something to do with the ease with which robots are roused to rebellion, aware as they are of the limited capacities they are allowed to use.

That Rossum’s robots have defects of their virtues is enough of a problem in its own right. But it becomes all the more serious in connection with a second implicit definition of friendly robots that Domin advances, this one based entirely on their purpose for humanity without any reference to the behaviors that would bring that end about. Echoing Marx, Domin looks forward to a day — in the Prologue he expects it to be in a decade — when robot production will have so increased the supply of goods as to make everything without value, so that all humans will be able to take whatever they need from the store of goods robots produce. There will be no work for people to do — but that will be a good thing, for “the subjugation of man by man and the slavery of man to matter will cease.” People “will live only to perfect themselves.” Man will “return to Paradise,” no longer needing to earn his bread by the sweat of his brow.

But caveat emptor: en route to this goal, which “can’t be otherwise,” Domin does acknowledge that “some awful things may happen.” When those awful things start to happen ten years later, Domin does not lament his desire to transform “all of humanity into a world-wide aristocracy. Unrestricted, free, and supreme people. Something even greater than people.” He only laments that humans did not have another hundred years to make the transition. Helena, now his wife, suggests that his plan “backfired” when robots started to be used as soldiers, and when they were given weapons to protect themselves against the human workers who were trying to destroy them. But Domin rejects her characterization — for that is just the sort of hell he had said all along would have to be entered in order to return to Paradise.

With such a grand vision in mind, it is hardly surprising that Domin is blinded to robot design issues that will look like mere potholes in the road. (Even Dr. Gall, for all his complicity in these events, notes that “People with ideas should not be allowed to have an influence on affairs of this world.”) For example, Domin has reason to believe that his robots are already being used as soldiers in national armies, and massacring civilians therein. But despite this knowledge, his solution to the problem of preventing any future robot unions, at a moment when he mistakenly believes that the robot rebellion has failed, is to stop creating “universal” robots and start creating “national” robots. Whereas “universal” robots are all more or less the same, and have the potential to consider themselves equals and comrades, “national” robots will be made in many different factories, and each be “as different from one another as fingerprints.” Moreover, humans “will help to foster their prejudices,” so that “any given Robot, to the day of its death, right to the grave, will forever hate a Robot bearing the trademark of another factory.”

Domin’s “national” robot idea is not merely an example of a utopian end justifying any means, but suggests a deep confusion in his altruism. From the start he has been seeking to free human beings from the tyranny of nature — and beyond that to free them from the tyranny of dependency on each other and indeed from the burden of being merely human. Yet in the process, he makes people entirely dependent on his robots.

That would be problematic enough on its own. But once the rebellion starts, plainly his goals have not changed even though Domin’s thinking about the robots has changed — and in ways that also brings the robots themselves further into the realm of burdened, dependent, tyrannized beings. First, the robots are to be no longer universal, but partisan, subject to the constraints of loyalty to and dependency on some and avowed hatred of others. And they will have been humanized in another way as well. In the Prologue, Domin would not even admit that robots, being machines, could die. Now they not only die, but have graves rather than returning to the stamping-mill.

Indeed, by rebelling against their masters, by desiring mastery for themselves, the robots apparently prove their humanity to Domin. This unflattering view of human beings, as it happens, is a point on which Domin and his robots agree: after the revolution, its leader, a robot named Damon, tells Alquist, who was once the company’s chief of construction and is now the lone human survivor, “You have to kill and rule if you want to be like people. Read history! Read people’s books! You have to conquer and murder if you want to be people!”

As for Domin’s goal, then, of creating a worldwide aristocracy in which the most worthy and powerful class of beings rules, one might say that indeed with the successful robot rebellion the best man has won. The only thing that could prove to him that the robots were yet more human would be for them to turn on themselves — for, as he says, “No one can hate more than man hates man!” But he fails to see that his own nominally altruistic intentions could be an expression of this same hatred of the merely human. Ultimately, Domin is motivated by the same belief of the Rossums that the humans God created are not very impressive — God, after all, had “no notion of modern technology.”

As for notions of modern technology, there is another obvious but far less noble purpose for friendly robots than the lofty ones their makers typically proclaim: they could be quite useful for turning a profit. This is the third definition of friendly robots implicitly offered by the Rossum camp, through Busman, the firm’s bookkeeper. He comes to understand that he need pay no mind to what is being sold, nor to the consequences of selling it, for the company is in the grip of an inexorable necessity — the power of demand — and it is “naïve” to think otherwise. Busman admits to having once had a “beautiful ideal” of “a new world economy”; but now, as he sits and does the books while the crisis on the island builds and the last humans are surrounded by a growing robot mob, he realizes that the world is not made by such ideals, but rather by “the petty wants of all respectable, moderately thievish and selfish people, i.e., of everyone.” Next to the force of these wants, his lofty ideals are “worthless.”

Whether in the form of Busman’s power of demand or of Domin’s utopianism, claims of necessity become convenient excuses. Busman’s view means that he is completely unwilling to acknowledge any responsibility on his part, or on the part of his coworkers, for the unfolding disaster — an absolution which all but Alquist are only too happy to accept. When Dr. Gall tries to take responsibility for having created the new-model robots, one of whom they know to be a leader in the rebellion, he is argued out of it by the specious reasoning that the new model represents only a tiny fraction of existing robots.

Čapek presents this flight from responsibility as having the most profound implications. For it turns out that, had humanity not been killed off by the robots quickly, it was doomed to a slower extinction in any case — as women have lost the ability to bear children. Helena is terrified by this fact, and asks Alquist why it is happening. In a lengthy speech, he replies,

Because human labor has become unnecessary, because suffering has become unnecessary, because man needs nothing, nothing, nothing but to enjoy … the whole world has become Domin’s Sodom! … everything’s become one big beastly orgy! People don’t even stretch out their hands for food anymore; it’s stuffed right in their mouths for them … step right up and indulge your carnal passions! And you expect women to have children by such men? Helena, to men who are superfluous women will not bear children!

But, as might be expected given his fatalist utopianism, Domin seems unconcerned about this future.

Helena Glory offers a fourth understanding of what a moral robot would be: it would treat human beings as equals and in turn be treated by human beings as equal. Where Domin overtly wants robot slaves, she overtly wants free robots. She comes to the island already an advocate of robot equality, simply from her experiences with robots doing menial labor. Once on the island she is unnerved to find that robots can do much more sophisticated work, and further discomfited by her inability, when she encounters such robots, to distinguish between them and humans. She says that she feels sorry for the robots. But Helena’s response to the robots is also — as we might expect of humans in response to other humans — ambivalent, for she acknowledges that she might loathe them, or even in some vague way envy them. Much of the confusion of her feelings owes to her unsettling discovery that these very human-looking and human-acting robots are in some ways quite inhuman: they will readily submit to being dissected, have no fear of death and no compassion, and are incapable of happiness, desire for each other, or love. Thus it is heartening to her to hear of Robotic Palsy — for, as noted, the robots’ defiance suggests to her the possibility that they do have some kind of soul after all, or at least that they should be given souls. (It is curious, as we will see, that Helena both speaks in terms of the soul and believes it is something that human beings could manufacture.)

Helena’s wish for robot-human equality has contradictory consequences. On the one hand, we can note that when the robot style of dress changes, their new clothes may be in reaction to Helena’s confusion about who is a robot and who is a human. In the Prologue, the robots are dressed just like the human beings, but in the remainder of the play, they are dressed in numbered, dehumanizing uniforms. On the other hand, Helena gets Dr. Gall to perform the experiments to modify robots to make them more human — which she believes would bring them to understand human beings better and therefore hate them less. (It is in response to this point that Domin claims no one can hate man more than man does, a proposition Helena rejects.) Dr. Gall changes the “temperament” of some robots — they are made more “irascible” than their fellows — along with “certain physical details,” such that he can claim they are “people.”

Gall only changes “several hundred” robots, so that the ratio of unchanged to changed robots is a million to one; but we know that Damon, one of the new robots sold, is responsible for starting the robot rebellion. Helena, then, bears a very large measure of responsibility for the carnage that follows. But this outcome means that in some sense she got exactly what she had hoped for. In a moment of playful nostalgia before things on the island start to go bad, she admits to Domin that she came with “terrible intentions … to instigate a r-revolt among your abominable Robots.”

Helena’s mixed feelings about the objects of her philanthropy — or, to be more precise, her philanthropoidy — help to explain her willingness to believe Alquist when he blames the rebellious robots for human infertility. And they presage the speed with which she eventually takes the decisive action of destroying the secret recipe for manufacturing robots — an eye for an eye, as it were. It is not entirely clear what the consequences of this act might be for humanity. For it is surely plausible that, as Busman thinks, the robots would have been willing to trade safe passage for the remaining humans for the secret of robot manufacturing. Perhaps, under the newly difficult human circumstances, Helena could have been the mother of a new race. But just as Busman intended to cheat the robots in this trade if he could, so too the robots might have similarly cheated human beings if they could. All we can say for sure is that if there were ever any possibility for the continuation of the human race after the robot rebellion, Helena’s act unwittingly eliminates it by removing the last bargaining chip.

In Čapek’s world, it turns out that mutual understanding is after all unable to moderate hatred, while Helena’s quest for robot equality and Domin’s quest for robot slavery combine to end very badly. It is hard to believe that Čapek finds these conclusions to be to humanity’s credit. The fact that Helena thinks a soul can be manufactured suggests that she has not really abandoned the materialism that Domin has announced as the premise for robot creation. It is significant, then, that the only possibility for a good outcome in the play requires explicitly abandoning that perspective.

We see the fifth and final concept of friendly robots at the very end of the play, in Alquist’s recognition of the love between the robots Primus and Helena, a robotic version of the real Helena, which Gall created, doubtless out of his unrequited love for the real woman. At this point in the story, Alquist is the last surviving human being. The robots task him with saving them, as they do not know the secret of robot manufacturing and assume that, as a human being who worked at the factory, he must. Alquist tries but fails to help them in this effort; but as the play draws to a conclusion, his attention focuses more and more on robot Helena.

Rather tactlessly, Gall had said of the robot Helena to the original, “Even the hand of God has never produced a creature as beautiful as she is! I wanted her to resemble you.” But the beautiful Helena is, in his eyes, a great failure: “she’s good for nothing. She wanders about in a trance, vague, lifeless — My God, how can she be so beautiful with no capacity to love? … Oh, Helena, Robot Helena, your body will never bring forth life. You’ll never be a lover, never a mother.” This last, similarly tactless, point hits human Helena very hard. Gall expected that, if robot Helena ever “came to,” she would kill her creator out of “horror,” and “throw stones at the machines that give birth to Robots and destroy womanhood.” (Of course, human Helena, whose womanhood has been equally destroyed, already has much of this horror at humanity, and it is her actions which end up unwittingly ensuring the death of Gall, along with most of his colleagues.)

When robot Helena does “come to,” however, it is not out of horror, but out of love for the robot Primus — a love that Alquist tests by threatening to dissect one or the other of them for his research into recreating the formula for robot manufacture. The two pass with flying colors, each begging to be dissected so that the other might live. The fact that robot Helena and Primus can love each other could be seen as some vindication of Domin’s early claim that nature still plays a role in robot development, and that things go on in the robots which he, at least, does not claim to understand. Even a simplified whole, it would seem, may be greater than the sum of its parts. But Alquist’s concluding encomium to the power of nature, life, and love, all of which will survive as any mere inanimate or intellectual human creation passes away, goes well beyond what Domin would say. Alquist’s claim that robot Helena and Primus are the new Adam and Eve is the culmination of a moral development in him we have watched throughout the play.

Čapek’s conception of Alquist’s developing faith is usefully understood by contrast with Nana, Helena Glory’s nurse. She is a simple and vehement Christian, who hates the “heathen” robots more than wild beasts. For her, the events of the play confirm her apocalyptic beliefs that mankind is being punished for having taken on God-like prerogatives “out of Satanic pride.” There is even a bit of mania about her: “All inventions are against the will of God,” she says, as they represent the belief that humans could improve on God’s world. Yet when Domin seeks to dismiss her views out of hand, Helena upbraids him: “Nana is the voice of the people. They’ve spoken through her for thousands of years and through you only for a day. This is something you don’t understand.”

Alquist’s position is more complicated, and seems to develop over time. When, in the Prologue, Helena is meeting the other men who run the factory and each is in his own way defending what the company is doing, Alquist is almost completely silent. His one speech is an objection to Domin’s aspiration to a world without work: “there was something good in the act of serving, something great in humility…. some kind of virtue in work and fatigue.” Ten years later, in a private conversation with Helena, he allows that for years he has taken to spending all his time on building a brick wall, because that is what he does when he feels uneasy, and “for years I haven’t stopped feeling uneasy.” Progress makes him dizzy, and he believes it is “better to lay a single brick than to draw up plans that are too great.”

Yet if Alquist has belief, it is not well-schooled. He notes that Nana has a prayer book, but must have Helena confirm for him that it contains prayers against various bad things coming to pass, and wonders if there should not be a prayer against progress. He admits to already having such a prayer himself — that God enlighten Domin, destroy his works, and return humanity to “their former worries and labor…. Rid us of the Robots, and protect Mrs. Helena, amen.” He admits to Helena that he is not sure he believes in God, but prayer is “better than thinking.” As the final cataclysm builds, Alquist once again has little to say, other than to suggest that they all ought to take responsibility for the hastening massacre of humanity, and to say to Domin that the quest for profit has been at the root of their terrible enterprise, a charge that an “enraged” Domin rejects completely (though only with respect to his personal motives).

But by the end of the play, Alquist is reading Genesis and invoking God to suggest a sense of hope and renewal. The love of robot Helena and Primus makes Alquist confident that the future is in greater hands than his, and so he is ready to die, having seen God’s “deliverance through love” that “life shall not perish.” Perhaps, Alquist seems to imply, in the face of robot love, God will call forth the means of maintaining life — and from a biblical point of view, it would indeed be no unusual thing for the hitherto barren to become parents. Even short of such a rebirth, Alquist finds comfort in his belief that he has seen the hand of God in the love between robot Helena and Primus:

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth…. And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good.” … Rossum, Fabry, Gall, great inventors, what did you ever invent that was great when compared to that girl, to that boy, to this first couple who have discovered love, tears, beloved laughter, the love of husband and wife?

Someone without that faith will have a hard time seeing such a bright future arising from the world that R.U.R. depicts; accordingly, it is not clear that we should assume Alquist simply speaks for Čapek. What seems closer to the truth for eyes of weaker faith is that humans, and the robots created in their image, will have alike destroyed themselves by undercutting the conditions necessary for their own existences. Nature and life will remain, as per Alquist’s encomium, but in a short time love will be extinguished.

Today’s thinkers about moral machines could dismiss R.U.R. as an excessively “Hollywood” presentation of just the sort of outcome they are seeking to avoid. But though Čapek does not examine design features that would produce “friendly” behavior in the exact same way they do, he has at the least taken that issue into consideration, and arguably with much greater understanding and depth. Indeed, as we have seen, it is in part the diversity of understandings of Friendly AI that contributes to the play’s less than desirable results. Furthermore, such a dismissive response to the play would not do justice to the most important issue Čapek tackles, which is one that the present-day AI authors all but ignore: the moral consequences for human beings of genuinely moral machines.

For Čapek, the initial impulse to create robots comes from old Rossum’s Baconian sense that, with respect even to human things, there is every reason to think that we can improve upon the given — and thereby prove ourselves the true masters of nature, unseating old superstitions about Divine creation. You could say that from this “frightful materialist” point of view, as Domin described it, we are being called to accept responsibility for — well, everything. But what old Rossum and his son find is that it is much harder to reproduce — let alone improve upon — the given than they thought. Their failure at this complete mastery opens the door to such success as young Rossum can claim: the creation of something useful to human beings. On this basis Domin can establish his grand vision of reshaping the human condition. But that grand vision contains a contradiction, as is characteristic of utopian visions: Domin wants to free us from the ties of work and of dependence, or at least from dependence on each other — in short, he wants to be responsible for changing the human condition in such a way as to allow people to be irresponsible.

Today’s authors on machine morality, focused as they are on the glories of an AI-powered, post-human future, are unwittingly faced with the same problem, as we will see. But it must be noted first how they also operate on the same materialist premises that informed the Rossums’ efforts. It was this materialism that made it possible for the play’s robot creators to think they could manufacture something that was very much like a human being, and yet much simplified. They were reductionist about the characteristics necessary to produce useful workers. Yet that goal of humanlike-yet-not-human beings proved to be more elusive than they expected: You can throw human characteristics out with a pitchfork, Čapek seems to say, but human creations will reflect the imperfections of their creators. Robotic Palsy turns into full-fledged revolt. People may have been the first to turn robots against people; the modified robots who led the masses may have been less simple than the standard model. But in the end, it seems that even the simplified versions can achieve a terrible kind of humanity, a kind born — just as today’s AI advocates claim we are about to do as we usher in a post-human future — through struggling up out of “horror and suffering.”

Wallach and Allen more than Yudkowsky are willing to model their moral machines on human moral development; Yudkowsky prides himself on a model for moral reasoning shorn of human-like motivations. Either way, are there not reasons to expect that their moral machines would be subject to the same basic tendencies that afflict Čapek’s robots? The human moral development Wallach and Allen’s machines will model involves learning a host of things that one should not do — so they would need to be autonomous, and yet not have the ability to make these wrong choices. Something in that formulation is going to have to give; considering the split-second decisions that Wallach and Allen imagine their moral machines will have to make, why should we assume it will be autonomy? Yudkowsky’s Friendly AI may avoid that problem with its alien style of moral reasoning — but it will still have to be active in the human world, and its human subjects, however wrongly, will still have to interpret its choices in human terms that, as we have seen, might make its advanced benevolence seem more like hostility.

In both cases, it appears that it will be difficult for human beings to have anything more than mere faith that these moral machines really do have our best interests at heart (or in code, as it were). The conclusion that we must simply accept such a faith is more than passingly ironic, given that these “frightful materialists” have traditionally been so totally opposed to putting their trust in the benevolence of God, in the face of what they take to be the obvious moral imperfection of the world. The point applies equally, if not more so, to today’s Friendly AI researchers.

But if moral machines will not heal the world, can we not at least expect them to make life easier for human beings? Domin’s effort to make robot slaves to enhance radically the human condition is reflected in the desire of today’s authors to turn over to AI all kinds of work that we feel we would rather not or cannot do; and his confidence is reflected even more so, considering the immensely greater amount of power proposed for AIs. If it is indeed important that we accept responsibility for creating machines that we can be confident will act responsibly, that can only be because we increasingly expect to abdicate our responsibility to them. And the bar for what counts as work we would rather not do is more readily lowered than raised. In reality, or in our imaginations, we see, like Adam Smith’s little boy operating a valve in a fire engine, one kind of work that we do not have to do any more, and that only makes it easier to imagine others as well, until it becomes harder and harder to see what machines could not do better than we, and what we in turn are for.

Like Domin, our contemporary authors do not seem very interested in asking the question of whether the cultivation of human irresponsibility — which they see, in effect, as liberation — is a good thing, or whether (as Alquist would have it) there is some vital connection between work and human decency. Čapek would likely connect this failure in Domin to his underlying misanthropy; Yudkowsky’s transhumanism begins from a distinctly similar outlook. But it also means that whatever their apparently philanthropic intentions, Wallace, Allen, Yudkowsky, and their peers may be laying the groundwork for the same kind of dehumanizing results that Čapek made plain for us almost a century ago.

By design, the moral machine is a safe slave, doing what we want to have done and would rather not do for ourselves. Mastery over slaves is notoriously bad for the moral character of the masters, but all the worse, one might think, when their mastery becomes increasingly nominal. The better moral machines work, the more we will depend on them, and the more we depend on them, the more we will in fact be subject to them. Of course, we are hugely dependent on machines already, and only a fringe few would go so far as to say that we have become enslaved to them. But my car is not yet making travel decisions for me, and the power station is not yet deciding how much power I should use and for what purposes. The autonomy supposed to be at the root of moral machines fundamentally changes the character of our dependence.

The robot rebellion in the play just makes obvious what would have been true about the hierarchy between men and robots even if the design for robots had worked out exactly as their creators had hoped. The possibility that we are developing our “new robot overlords” is a joke with an edge to it precisely to the extent that there is unease about the question of what will be left for humans to do as we make it possible for ourselves to do less and less. The end of natality, if not an absolutely necessary consequence of an effort to avoid all work and responsibility, is at least understandable as an extreme consequence of that effort. That extreme consequence is not entirely unfamiliar in a world where technologically advanced societies are experiencing precipitously declining birthrates, and where the cutting edge of transhumanist techno-optimism promises an individual Protean quasi-immortality at the same time as it anticipates what is effectively the same human extinction that is achieved in R.U.R., except packaged in a way that seems nice, so that we are induced to choose rather than fight it.

The quest to take responsibility for the creation of machines that will allow human beings to be increasingly irresponsible certainly does not have to end this badly, and may not even be most likely to end this badly. Were practical wisdom to prevail, or if there is inherent in the order of things some natural right, or if, as per Alquist and Nana, we live in a Providential order, or if the very constraints of our humanity will act as a shield against the most thoroughly inhumane outcomes, then human beings might save themselves or be saved from the worst consequences of our own folly. By partisans of humanity, that is a consummation devoutly to be wished. But it is surely not to be counted upon.

After all, R.U.R. is precisely a story about how the human soul, to borrow Peter Lawler’s words, “shines forth in and transforms all our thought and action, including our wonderful but finally futile efforts to free ourselves from nature and God.” Yet the souls so exhibited are morally multifaceted and conflicted; they transform our actions with unintended consequences. And so the ultimate futility of our efforts to free ourselves from nature and God exacts a terrible cost — even if, as Alquist believes, Providence assures that some of what is best in us survives our demise.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?