When Apple announced this summer that Vision Pro, its new virtual reality goggles, will be available for purchase in early 2024, the reaction was mixed. Some gawked at the price tag of $3,499. Others derided Apple for its lonely vision of the future. Yet many who have gotten an early try of the device have been blown away.

What matters here is not just the new technology itself but the milestone it will likely mark for the development of other devices. Apple Vision Pro is not the first VR headset, nor will it be the last. But as with the iPod, the iPad, the iPhone, and the Apple Watch, none of which were the first of their kinds, Apple products have a way of becoming the standard by which other devices are judged. Canny observers in the world of VR technology are paying attention. Despite the price tag, Vision Pro has the potential, like Apple’s premium devices in the past, to pave the way for mass adoption in the future, as the price comes down and the ecosystem around the device matures.

Apple has a well-practiced playbook for developing epochal devices: build best-in-class hardware, design an operating system that’s powerful yet feels familiar, and incentivize app developers to push the device to its limits. Developers, eager to begin building apps for when the device launches next year, have been clamoring for access to its software kits and testing labs. And Apple promises something else that may eventually lead to mass adoption: Vision Pro is not just for gaming or gimmicks, it is for all the things you already do with other devices — work, entertainment, and socializing.

If Vision Pro gains the traction Apple is hoping for, it will change virtual reality from a stubbornly niche hobbyist pursuit to one of the main ways we interact with the world and each other. Its coming arrival is therefore worth examining as part of a larger trajectory of how “personal devices” are becoming, well, ever more personal indeed.

Device designers have long struggled to overcome a fundamental barrier: the interface, the tactile intermediary between the device and you. Apple has always worked hard to perfect the interface, to make it ever thinner and bring the device ever closer to us. Vision Pro is a reminder of how remarkably successful this project has been — and that it is far from finished.

And it is a sign too of what is still to come, not only in the world of virtual reality goggles but beyond it.

Every one of the personal computer devices we now use — phones, televisions, laptops, watches — already felt familiar to us when they were first introduced. That is because product designers rely on material culture to provide familiar references. Material culture, the values and principles that are baked into the physical stuff we make and use, provides archetypal shapes, objects, interactions, affordances, practices, and concepts that device makers riff on. In this way, designers ground their innovations in the reality we already know.

The first computers of the 1940s and 1950s were large, room-sized machines, mechanical beasts akin to the ones our forebears had toiled at in the factories of the early industrial era. When desktop computers became widely available in the late 1970s, we saw them as appliances, task-based devices to be put on a desk or counter and used when needed, like a KitchenAid. Laptops relied on our physical comfort and familiarity with paper notebooks, and indeed are often called that. Cell phones were just telephones, but they also carved out a spot in the exclusive realm of pocket stuff, together with keys and wallet forming a new hallowed trinity. Smart watches riffed on the wristwatch, the glowing television riffed on the family hearth.

So what pre-existing cultural artifact do virtual reality goggles arise from? One intriguing possibility is sunglasses. Perhaps the comparison is surprising — VR goggles are for dorks, and don’t you just look cool when you wear shades?

But another way to think about why shades are cool is that they make you seem impervious, unbothered. Sunglasses conceal intent, attention, and mood. They can even offer retreat for those for whom naked reality is too much. A 2018 study of social anxiety notes that for some people, “sunglasses … operate as a social shield between the anxious self and the invasive gaze of others.” One study participant remarked: “I [take] taxis everywhere. Literally, I go in with my sunglasses on and block out the whole world.”

Like sunglasses, virtual reality goggles obscure your eyes from others, and alter your vision, but still let you see. Apple Vision Pro is designed to make it seem as if you are looking through the goggles, seeing what’s right in front of you. Like the Terminator, when you wear the goggles you see a “mixed reality,” a live video feed of the physical world overlaid with digital additions. To give you a more immersive experience, the feed populates your physical space with digital interfaces, taking the type of prompts you would normally find on your computer home screen and laying them over your actual home. There is even a dial that lets you adjust how much of the real reality you want to see.

Vision Pro, in other words, cuts the glare from the world better than shades ever did.

In having its designs draw on familiar objects, Apple aims to ease you into the novel world of its devices. But this is not the only way Apple wants to make things easy for you.

More than any other modern device maker, Apple wants to perfect interfaces — the tactile, visual, and cognitive boundaries between you and its devices. To establish and maintain market dominance, Apple’s designers continuously work on improving their interfaces, narrowing the gap between what a user wants to do and how fast and faithfully the device does it.

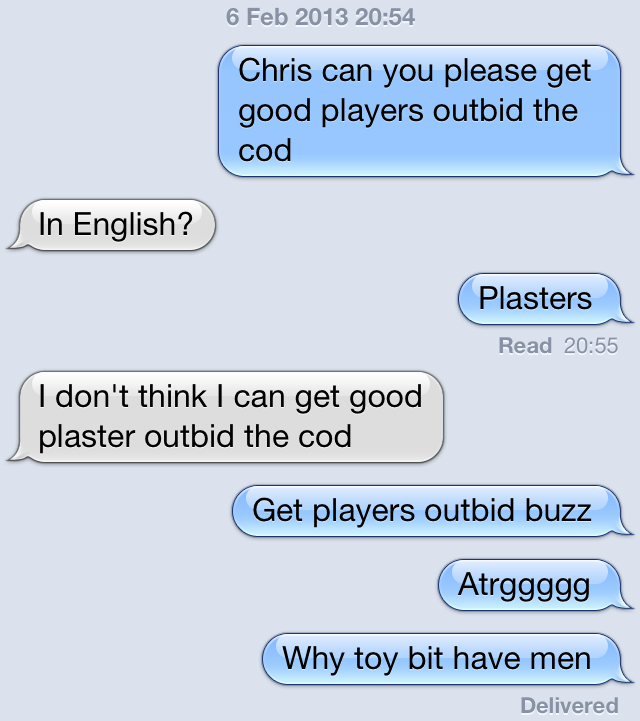

Every interface throws up roadblocks between the user’s intent and the device’s function. This is the problem of friction. Early smartphones, like the Samsung S1, were slow and unintuitive. Older Apple hardware struggles under the weight of new software updates, slowing it down (and making you consider buying an upgrade). Even the best-designed interfaces occasionally misinterpret an action you perform — a keystroke, a touch — yielding, among other things, a whole genre of Buzzfeed listicles of mistyped texts.

Apple has been ruthless about finding these obstacles and removing them. And while errors and frustrations persist, interfaces are still getting more frictionless. For example, Apple’s Face ID, which unlocks your phone when you pick it up and look at it, makes it easier and smoother to use your device on a whim. Responding by voice to a text you received on your Apple Watch saves you from having to pick up your phone and text a response. When wearing the Apple Vision Pro, you will apparently be able to open an app just by glancing at it. Designers want to get you as close as possible to technological fulfillment.

What strategy is yielding such improvements? Device makers improve their interfaces in part by getting closer to your body, your space, by interpreting your subtle movements and glomming on to the acuity of your senses to break down yet more barriers between your intent and your action. Apple is quite clear about this process in its Vision Pro announcement video:

This is visionOS, Apple’s first-ever spatial operating system. It’s familiar, yet groundbreaking. You navigate with your eyes. Simply tap to select, flick to scroll, and use your voice to dictate. It’s like magic.

Apple is revealing here an obsessive focus common to device makers: It wants to bring you ever closer to its apps, entertainment, and social environments by steadily reducing your physical interactions with the device. The hope is that soon you will hardly have to do anything to the device at all. Instead, it will watch your eyes, face, head, and hands to intuit your meaning. Apple’s designers believe that it is easier and more casual to gesture in the air or to glance at an app icon than it is to hold something in your hand and tap tiny buttons with fat fingers. The interface is no longer the device itself, but our bodies and the space around us.

But there is an oddity about Apple’s strategy. In order to make the interface frictionless, Vision Pro also gets closer to the sensory organs than sunglasses ever did — or headphones or any other reference we can draw on.

We could say in defense of Vision Pro: But it still shows you the real world! Perhaps it even puts us in touch with reality better than the smartphones it’s going to replace. Instead of having to gaze away from the world to check our email, we can see them both at once, the full digital along with the full physical.

But consider just how intimate this interface is. To detect what you want to do, Vision Pro has to place an extensive sensor array right up next to your eyes to gauge their movement. To give you a fully immersive video feed, it has to fully cover your eyes. This enhanced-reality approach has strange consequences. For example, when you FaceTime someone with Vision Pro, your interlocutor can no longer actually see your face. So the device has to synthesize your mood, intent, interest, and attention, and represent you to the other person as a realistic digital avatar.

However sophisticated our interfaces have gotten — buttons, dials, keyboards, laptop screens, smartphones — they have by and large still amounted to some physical thing, a thing we must manipulate with our hands, and stay focused on because it is just one thing in a visual field of many other things our eyes could look at. But if you want to replace material interfaces with immaterial ones — no more fat-fingered typos, only smooth eye movements and gestures — you can no longer just make another thing, you have to start replacing the senses too. In order to augment the eyes, you have to cover the eyes over.

The closer the device gets to realizing what you really want, the closer it must draw to your person. And the closer it draws to your person, the more it cuts you off from the world.

How much more can Apple close the gap?

There is a movement in material culture that may suggest that the logical next step in the future of personal devices is the implant. It is hard to say whether designers of mass-consumer tech will ever decide that their users can overcome the body horror accompanying hardware implants in skin, eyes, or brain, giving us the world Neal Stephenson imagined in The Diamond Age. But the current cultural trend toward broad acceptance of body modifications may not need to be much further advanced before mass consumers are primed to adopt the implant.

Non-surgical cosmetic procedures in the United States have increased seven-fold over the past twenty-five years. We inflate, contort, pinch, and squeeze our bodies into new forms at an unprecedented scale. In certain corners of the Internet, there is an obsession with body modification in a broad sense: with posture and pose as signs of power, with voice modification, jawlines and cheekbones, with the proliferation of health devices, diets, supplements, shape-wear, and silicone, and the ready availability of human growth hormone and sex hormones.

The upshot of body modification is that it allows us to transcend certain confines of our bodies. It works in service of those who for social, aesthetic, or emotional reasons feel the need to modify their bodies in order, for example, to attract a partner, receive the attention they desire, or match their chosen identity. The body becomes, in effect, an instrument to achieve a purpose.

And once we regard the body as an instrument, it can also become an interface, with implants serving as the input devices. Together, the body and its integrated devices can overcome the physical and mental limitations, the so-called “user errors” that hold back our interactions with devices, opening up a panoply of Internet-enabled possibilities. These kinds of devices already exist as aids for those with certain physical disabilities, much like the speaking device the late Stephen Hawking used as a way to communicate with the outside world when his physical faculties failed him.

It is by now well-known that innovations in one arena, such as space technology, foreground advancements in consumer tech. In the same way, cutting-edge research into device accessibility may pave the way for wide adoption later. One startup, Synchron, funded in part by Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, has reached an important milestone: in 2022, their Synchron Switch brain implant was used by a patient disabled by ALS to send a message via iPad. And Elon Musk’s venture, Neuralink, is forging ahead with its own brain–computer interface, receiving FDA clearance in May to begin its first human trial.

Why might these technologies succeed, despite their invasiveness and despite the controversy and criticism surrounding them? One answer is that we are still limited by our interfaces. After years of using touchscreen keyboards, our thumbs still butcher even simple sentences. Voice dictation was a logical next feature to offer, but it too is buggy. What if we could just think and have our intent acted upon? The perfect interface is no interface at all.

The promise of a true mind–body interface is to make the use of digital tools truly effortless. I would be lying if I said that I have never, when using a digital device, felt the seductive inklings of a smooth, frictionless experience. The Vision Pro promises to bring us closer to that. In Apple’s announcement video, the actors gesture gracefully and precisely in mid-air, navigating between virtual apps. Can this device, or future ones, deliver on the promise of effortlessness?

There are limits to what any device can do. The stubborn constraints of the body — its natural course from youth to old age, its limited attention span and mental plasticity, its recurring need for sleep and food, the imprecisions of hands and fingers and eye movements — are the ultimate problem for friction-eliminators. No matter how close to our bodies a device gets, it won’t be close enough to rule out these inconveniences entirely. But this way of putting it suggests that our bodies themselves are the problem, that eliminating friction would mean eliminating our bodies.

We seem only happy enough to be partners in the abolition of the body. Consider again the trend in now broadly accepted body modifications that presaged the Apple Vision Pro and that may offer ingress to the implants of the future. It is a trend that affects how all of us view ourselves and each other. Are any of us really happy with our body and its stubborn limitations? The technologies available to us for modifying our bodies help to warp the ideas we have in our heads about what other people want to see in our bodies, identities, personalities, voices, and minds.

And as the fleshly reality of our bodies drifts apart from the smooth, effortless digital image of ourselves, our concept of what our bodily self ought to be changes, too. This body dysmorphia leaves us dissatisfied with merely using post-processing filters to alter the photos and videos we take and share of ourselves. We may want to bake the filters in, to make the impossible proportions, pore sizes, skin tones, musculature, voices, posture, fat distributions, and facial structures we see every day permanent. We search out invasive surgical techniques, tricks of lighting and angle, tucks, pinches, snips, and stretches, pills and chemicals and dietary hacks, that mold us into what we think others desire of us. Failing these bodily remedies, we might instead seek relief in the digital world.

Once the tools are available, a quiet retreat from reality is all too easy to take advantage of. Consider how some people found solace in the physical retreat of wearing a face mask, even after the public health justifications for masks faded along with Covid deaths. A New York Times piece in March 2022 reported on a group of teenagers, one of whom made a heartbreaking admission:

Ultimately, Belle, 16, and her friends decided to keep their masks on for now, “not because of their views on the pandemic, mostly because of their views on themselves and how they think people are going to judge them,” Belle said. “Only seeing half of someone’s face for two years straight and then completely opening up to them, like, ‘Oh, here’s my face’ — you know, it’s a lot.”

Most of us do not have a strong enough sense of the indispensability of the body to resist having yet another layer of ourselves peeled away and a device put on us instead. Most of us already have devices too close to us, and our digital persona feels too real, and too far from our physical life, to resist the closing circle of each new epochal device. We need to get comfortable in our own skin again. To do this, we need courage and optimism.

We need courage because our bodies are unavoidably fragile, aging, and imperfect, constantly in need of care, maintenance, resources, and rest. That’s true of every single one of our bodies. Many have additional strikes against them: disease, chronic pain, injury, or chemical or hormonal imbalance. To be human is to have courage in the face of these impediments; it is impossible to go on living without some measure of courage.

We must also be optimistic. The body’s physical reality is better than the alien reality of the digital world. All of us are more beautiful than the most beautiful AI-generated model, because we are real and it is not. Digital technology is only useful insofar as it has a good effect here in the real world we all live in. We can order our technologies toward the flourishing of the body and of reality. We can make the device a useful instrument, realizing that it is dispensable, whereas our bodies are not.

The Apple Vision Pro wants to be your new eyes. But why are we so keen to replace our real ones? What is so lacking in them? Or what is so lacking in the physical world our eyes perceive that it must be “augmented” with the digital? Is there a positive vision of human flourishing on offer here? Digital-device culture is an experiment on a colossal scale, the results of which we have tried to measure in IPOs, quarterly growth rates, engagement metrics, and daily active users, not in human flourishing. But that is where we are incurring the real costs.

At the end of its announcement video, Apple calls the Vision Pro “a powerful way to relive our memories, a profound new way to be together.” Thinking of virtual experiences as powerful and profound is only possible in a world where our memories and our being together have been so impoverished by the substitutionary effects of device culture that we require high-tech scaffolding to experience power and profundity. There is much better on offer, if we don’t mind the clunky interface of the real world.

April 28, 2016

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?