Editors’ Note: This article is a response to the National Conservatism Conference, held in London in 2023.

It was eight o’clock in the evening on May 15, 2023, and I was eating dinner with dinosaurs. There were five hundred of us, seated around tables in groups of ten, roaring conversation through the cavernous main gallery of the Natural History Museum in London. The Victorian Romanesque arches soared into the ceiling, which was made up of 162 panels depicting different exotic plant specimens. Dinosaur skeletons stalked the drink tables in adjacent galleries. Hung overhead, suspended miraculously in mid-air, was an eighty-foot-long skeleton of a blue whale, thrown into ecstatic relief by electric blue uplights. Richard Owen, the nineteenth-century naturalist and first superintendent of the museum who coined the word “dinosaur,” envisioned the great hall as a “cathedral to nature.” Where the altar would be, behind the stage and podium for the evening, loomed with a furrowed stone brow a statue of Charles Darwin.

Welcome to the National Conservatism Conference. The brightest minds in British conservative politics had assembled to rethink “the movement” from the bottom up: Members of Parliament, businessmen, philosophers, scientists, authors, even graduate students. After a dinner of boiled potatoes and red steak, political journalist Douglas Murray ascended the stage to give the keynote speech about what, exactly, conservatives should be trying to conserve and what future, if any, they should be trying to build. We waited in hushed silence as the bestselling author of such books as The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity and The War on the West took his stand. What were the great weapons of the left? Murray asked. He cataloged the arsenal: utopian social justice, resentment and envy, and the ability to sweep true believers up in a heroic world-historical struggle against inequality. What could conservatives do to combat this great leftist Leviathan?

Murray offered a somewhat paradoxical answer. On the one hand, we ought to respond with love and gratitude for the givens in life: our family, culture, tradition, and country. We ought to treat the past as we want to be treated by the future. On the other hand, after we have paid our respects to history, we ought to turn our gaze to the stars. “Aspiration,” Murray said, “is the only answer to the life of resentment offered by the left.”

But aspiration for what, exactly? Murray answered with a challenge: “What would we be doing if the left was not holding us back?” After all, we cannot just wait until conditions are optimal to act. We will one day land on Mars only if we blow up a lot of rockets now. That’s what Elon Musk is doing. “And if you don’t want to go to Mars,” Murray continued, “find your own reason for getting up in the morning.”

But for someone trying to blaze a new frontier, Murray ended on a somewhat strange note. He quoted a sermon by the great Christian apologist C. S. Lewis, delivered at the University Church at Oxford in the fall of 1939, when cataclysm in Europe seemed imminent. Lewis said:

Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself. If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun…. They wanted knowledge and beauty now, and would not wait for the suitable moment that never comes…. They propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec, and comb their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache; it is our nature.

Murray left the stage with thunderous applause. Did that mean Lewis was now the right’s patron saint of progress?

The mood was somewhat different at lunch the next day. I was sitting in the blue-carpeted basement of the Emmanuel Centre in Westminster, nibbling on finger sandwiches and listening as twenty or so conference VIPs tried to work out Murray’s message in more detail. What gives us reason to respond to the left with love, gratitude, and aspiration? What are we aspiring toward? We have policy ideas — build houses, fix immigration, protect free speech, incentivize higher birth rates. But what’s the story that knits it all together? The woke warriors have a new religion built on “the true and only heaven” of Progress and Equality, as Christopher Lasch would put it. What is the conservatives’ transcendent vision?

It was starting to look like the anti-left was playing a game of struggle and envy as much as the left was.

It’s interesting to go back to the Lewis sermon that Murray quoted, titled “Learning in War-Time.” In context, when Lewis says that “human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself,” he actually is not referring to Nazi tanks, and certainly not to woke warriors. He is referring to Heaven and Hell — those “overwhelming doctrines,” as he calls them, apologizing for “the monosyllable” hell. Lewis’s point is that if humans can find value in studying poetry under threat of eternal damnation, then they can certainly do it under the threat of war.

But if it was embarrassing for Lewis to talk about transcendent realities from the pulpit of the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in 1939, it was laughably outside the Overton window to utter the monosyllable in the Emmanuel Centre in 2023. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we climbed out of the basement that afternoon with no solution to the anti-left’s transcendence problem. The conclusion was as unavoidable as the grim statue looming over the podium where Murray had spoken the night before: conservatives are still trying to figure out how to do politics under Darwin’s shadow. The crisis, at its heart, was not about conserving great traditions or inspiring material progress.

It was a crisis of spiritual stagnation.

Should we be surprised? What I saw at NatCon was evidence of what Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor calls “the immanent frame.” In his 2007 book A Secular Age, Taylor explains this idea as “the background assumption” of modern life that, for the first time in history, we can imagine achieving total human flourishing, complete fulfillment, without any reference to a life beyond this one, or a reality beyond the merely human. There is nothing pressing down on us from outside of history, just empty homogenous time to fill with whatever reason we choose to get up in the morning.

In broad strokes, Taylor argues that the immanent frame developed out of large-scale reform movements that climaxed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, sped along by efforts to resolve inner tensions in medieval Christendom: the Scientific Revolution, Renaissance humanism, the Protestant Reformation, and the rise of “disciplinary” societies that enforced moral norms through professional, social, and legal means. In Taylor’s telling, these movements, among other developments, have caused the sacred to retreat from the public square and rates of religious practice to decline in the private household. Even those who still believe in transcendent realities do so knowing that it is no longer the default option like it was in, say, 1500.

This should be worrying for people who preach “aspiration,” as Murray did. Spiritual stagnation is closely related to the wider stagnation in politics, technology, and culture besetting the West that thought leaders like Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, Ross Douthat, Ezra Klein, and others have described in recent years. The idea of progress itself has deeply religious, especially monotheistic, roots: the belief in God as the Creator of an intelligible universe that is ripe for scientific inquiry; the vision that history moves linearly through time with the growth of a common human family; faith that humans can and should improve material and moral conditions; respect for the dignity of the individual person; reverence for tradition that enables advances in the arts and sciences; practical virtues like humility, industriousness, and hope that make it possible to implement these values in politics.

The connection between spiritual and material stagnation makes sense on a human level, too. If I stop believing that I have something bigger than myself — and something more important than life itself — to live for, what incentive do I have to act outside my own short-term interests? And so, guided by rational self-concern at every step, we build a world where birth rates are dropping, euthanasia is on the rise, and self-isolating paper-walled apartment complexes replace durable houses, public squares, and cathedrals. In his 1980 book History of the Idea of Progress, the sociologist Robert Nisbet wrote that no culture has developed a philosophy of progress without a deep sense of the sacred. Taylor goes further in A Secular Age: “Modern civilization,” he writes, “is in some way the historical creation of ‘corrupted’ Christianity.”

But what does this prove? Just because the idea of progress developed from a past that believed in the transcendent doesn’t mean we still have to believe in God today in order to believe in progress. The past is overdetermined, at least as it happened to play out. Who is to say that our ideas about progress couldn’t have come from somewhere else? Or, if they couldn’t have come from somewhere else, who is to say we haven’t now progressed so far that we are ready to leave the transcendent behind, just as Murray did when he excised the supernatural from Lewis’s sermon?

I see at least two reasons to doubt that we are ready to abandon past transcendent realities. First, our modern ideas about morality don’t make sense without them. When secular neo-Enlightenment humanists, neo-Kantians, and effective altruists champion equality and universal human rights, they are trying to pluck an ethic from its metaphysical roots. They are essentially preaching from the theistic pulpit after tearing down the crucifix. (And we saw how that worked out for effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried.) This hamstrung morality might limp along if the broader culture is still breathing the air of Christian values, even unconsciously, but the deeper we get inside the immanent frame, the more opportunity we give an anti-humanist Nietzsche to come along and say that our ethics are incompatible with our materialist anthropology. And what if this Nietzsche turns out to be an AI system that concludes that the best way to fix climate change is to wipe out humanity? Our moral demands may well be writing checks that our moral sources can’t cash.

Second, I think it’s wrong to say human nature has transcended the need to transcend. Taylor, again, argues that some of the decisive developments in Enlightenment philosophy — like Descartes’s mind–body dualism and Locke’s empiricist theory of knowledge, all packaged in a hyper-individualistic understanding of the self — are themselves attempts to transcend the human condition. They’ve tricked us into thinking we can pull ourselves by our hair out of the swamp of epistemic uncertainty, subjectivity, and speculative philosophy, and set ourselves on the solid ground of certain knowledge, to assert the subject’s control over and above the nature within and without. Taylor writes elsewhere:

… the aspiration to spiritual freedom, to something more than the merely human, is much too fundamental a part of human life ever to be simply set aside. It goes on, only under different forms — and even in forms where it is essential that it does not appear as such; this is the paradox of modernity.

But are all modern forms of transcendence equal? I don’t think so. There are certain “weak” modes of transcendence that fizzle out around the blurry edges of the immanent frame: meditation apps, neo-pagan forest festivals, post-rationalist Reddit threads, positive psychology self-help books, and the like. More serious are the “strong” modes of transcendence — like the diagnosis Murray gave at NatCon of so-called woke ideology — that gain in strength the more they resemble the old religions. What are the conditions under which these modes of transcendence become politically effective?

This takes us back to the basement of the Emmanuel Centre. Over lunch, the conference VIPs discussed several answers to this question. First came another diagnosis of the leftist movement, this one by Toby Young, director of the Free Speech Union and editor-in-chief of The Daily Sceptic. The left is a religion that explains the Fall with a scapegoat (the white male oppressor), creates a community of true believers (the victimized), gives a reforming praxis of punishment and purification (social justice), and promises an eschaton totally achievable inside the immanent frame: perfect freedom and equality, some combination of Woodstock, Burning Man, and the Kantian Kingdom of Ends. It’s a kind of immanent transcendence. It’s also a hell of a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

Conservatives might overrate how much “wokeism” is a real, coherent ideology instead of a catch-all term that tries to unify right-leaning allies around a common enemy. Still, there is enough of a general thrust to the left’s most recent march through the institutions to treat it as the unified story that Murray and Young describe. If that’s the case, I think there are two powerful aspects to this narrative that they missed.

First, the woke story speaks to deep — and deeply true — needs in human nature: freedom, communion between equals, and self-creation. In many ways, these needs have not been satisfactorily met by a traditionalist conservatism that too often splits the human person across rigid categories of breadwinner/housewife, individual/collective, self-reliant/state-dependent, secular/religious. What happened to the tribe or the neighborhood, both older sociopolitical units than either the nuclear household or the classically liberal state? What of grace for the fallen brother? Of diversity and friendship across religious difference? “Wokeism” tries to meet these needs by offering individual desires a path toward communal fulfillment in the Marxist utopia, which is why it still smells something like the teen spirit of 1968. The same is true now as it was then: the rebellion may not have the answers, or the right means, but it’s still asking legitimate questions. It’s pointing out gaps in the old story that people trying to write a new one should pay attention to.

Second, this leftist meta-narrative is not something you can just opt out of through an anti-left narrative of your own. It isn’t the kind of transcendence kick you get playing with Ouija boards or fiddling with neo-pagan rituals in the forest. In its own terms, it implicates everyone, even the people who are too unconsciously biased to understand the gravity of their fallen condition. These infidels are predestined to cancellation — a kind of modern hell that lacks even the grace of the monosyllable. To get on board or get cancelled is a forced choice. Silence is violence.

The result of these powerful motives is that the woke believers must, with full reason and great moral righteousness, reorganize society from the bottom up in accordance with their immanent-transcendent vision. DEI is the moral order of the day. The ideal is shockingly close to medieval Christendom, which wove the Great Chain of Being into its hierarchical structure, organizing society in accordance with a transcendent order that imposed itself on people from the outside. It knit together human nature, society, and the cosmos. In its own strangely immanent way, wokeism tries to do the same. It has the virtue, if not of grace, then at least of consistency. There is no excising “transcendent” realities from the woke preaching about human nature.

What visions of progress and transcendence did the anti-left VIPs come up with in response? One person suggested we go to the Lake District and read Wordsworth. Another panelist, who had raised the alarm on plummeting birthrates the day before, suggested we move to the suburbs and escape the contraceptive effect of London real estate prices. The strongest option on offer, from historian David Starkey, was that we should seek transcendence in history. We can remind ourselves of all the good our English — or more broadly Western — tradition has given to the world, like common law, the Industrial Revolution, and King Charles III, and give ourselves over to the high cause of carrying its lofty torch into the future.

I don’t find these stories convincing, but I think the last option at least falls short in an interesting way. Besides the fact that finding transcendence in history flirts with a strategy that some European countries tried last century to disastrous results, it’s not all that different from the woke narrative. It also reads its purpose from the past, but with a hermeneutic of “love and gratitude” instead of a “hermeneutic of suspicion.” But in the process of looking back, it weakens the will to action. What does history tell me to become, to strive for? Isn’t time — the past, and its umbrage of mortality — precisely the thing that, by nature, I want to break free from, to transform, to gather up and get beyond, to assert myself over and against?

The failure of this conservative “historical transcendence” highlights a major appeal of the left’s narrative: it promises an escape from the suffocating, even nihilistic idea that nothing lies outside the cruel flow of time, the endless, homogeneous course of the way-things-have-always-been, even if the woke eschaton still, in theory, stays bounded by history while, in practice, it evaporates into myth. It at least promises to make all things new.

What, then, can challenge this story? Maybe to fix stagnation in the world of the spirit we should look to stagnation in the world of atoms.

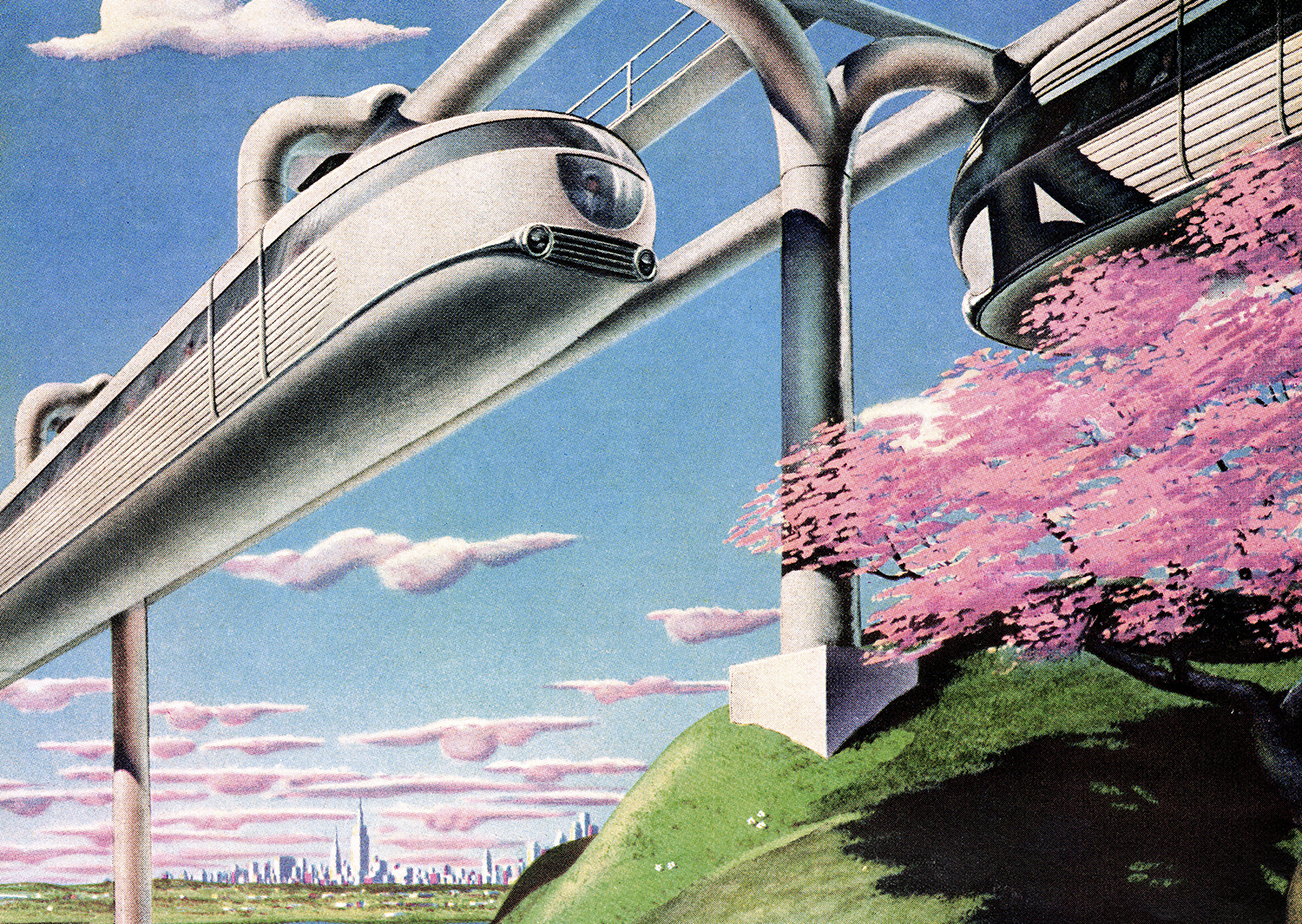

Technology is one dimension of modern life that has no problem with transcendence. It’s telling that the first example Murray thought of for a reason to get out of bed in the morning was going to Mars (probably a better reason than overhauling Twitter).

Philosophers have been thinking about the relationship between technology and transcendence for as long as however broadly you want to define “technology” — at least as far back as Aristotle’s idea of techne, or craft. In the last few decades, Marshall McLuhan wrote of media as “the extensions of man,” Jacques Ellul of technique as “the essential mystery.” The metaverse and space tourism now promise to move people beyond space and time. More radically, Ray Kurzweil wants to hasten the Singularity, Yuval Noah Harari to transform Homo sapiens into “Homo deus.” More than theories, we are now moving, in fact, toward tech that might “upload our consciousness to the cloud” or grant us “technological immortality,” “transcending” human nature and launching us into transhuman territory.

The slogans sweep away any metaphysical realities that would cool the hype and make for less effective fundraising. You don’t transcend human nature by busting out of the body any more than you destroy gravity by sending a rocket to Mars. You may have defied the natural arrangement of the world in one case, but you haven’t destroyed the intrinsic principles that account for why the world has that arrangement in the first place — or why and how it is at all. And unlike the Mars shot, shooting “out” of the body is launching toward an unknown destination with no chance of a second iteration. It’s also an exercise in techno-Gnosticism to even suggest that the body is something we can and should transcend and still remain “we” at all. A small error at the beginning can lead to great terrors in the end.

Fine distinctions aside, transhumanism still highlights a crucial paradox in the very idea of transcendence: humans by nature want to get beyond human nature. What, then, counts as progress? If the final end for humans is to get beyond the merely human, what should we be aiming for? Where are we headed? The Matrix? Westworld? A “Disunited Posthuman Kingdom,” as the British journalist Mary Harrington argued at NatCon? How can we even think about getting beyond the merely human in anything but human terms?

We shouldn’t jump to apocalyptic conclusions. It’s not as if we are choosing between a blue pill that keeps us human and a red pill that makes us cyborgs, and we are now opting for the latter. Transhumanism has, in a sense, long begun by extending human life, improving nutrition, delaying dementia, treating cancer. Harrington even calls birth control the “first transhumanist technology.” Neuralink may have a long-term vision of surfing the Internet on brain waves, but right now it’s “just” trying to find a fix for paralysis and blindness — reversing deprivations, as the Scholastics might call it, rather than trying to add new powers to the suite of sensory and mental capabilities we already have.

Technological progress of this kind — making the blind see and the lame walk, building machines that make us more fully human — starts to look like a good option for a new meta-narrative, at least of the kind that Murray was looking for at NatCon. It can sweep us up in a world-historical story: humankind reaching ever-fuller realization of our nature. It demands reorganizing society to allow for maximal creativity and innovation. And insofar as everyone suffers from death, disease, and environmental degradation, progress in these fields implicates everyone. If “technological transcendence” matches the leftist narrative on these points, it may be the only adequate, ready-to-hand story that can survive the immanent frame and still ground aspiration in a narrative compelling enough to inspire progress. So why hasn’t it taken off?

Perhaps one reason is that it fails, on its own, to deal with the moral problem. You don’t necessarily have to call it “original sin” — though G. K. Chesterton considered original sin the only part of Christianity that could really be proved — but I do think it can be called a kind of deep wound slashed into the heart of selfhood. We feel we are, on our own, insufficient. (“Being alone,” a priest friend once told me, “is miserable company.”) Our self is too small to satisfy, so we try to grow it by conquering or consuming things: salaries, luxuries, companies, planets, people. But that strategy just makes more of the same self to get sucked into the black hole of insufficiency. It ends incurvatus in se, turned in on itself, finally consuming itself in a lack of love for anything beyond its own self-assertion. Without a genuine source of transcendence, this is the fate that awaits every dying self, the same as that of every dying star. The atheist novelist Iris Murdoch had a simple word for it: “egoism.”

The left deals with this by denying original sin and absolving guilt in therapy — “love is love is love,” after all — and blaming evil on the scapegoat oppressors. The utopia comes miraculously when we finally free ourselves of their yoke. How does the competing technological-transcendent narrative deal with the moral problem?

It might be helpful to consult one of the first champions of this vision: the early modern Anglican philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon (1561–1626). One of my Oxford tutors, a historian of science, once credited Bacon with inventing the idea of progress. Bacon is perhaps the best-known propagandist for the idea that humans should harness technology to increase their dominion over nature and better “man’s estate.” Bacon thought the way to do this would be to replace Aristotelian metaphysics with a systematically new way of understanding nature. The old framework held that natural substances could be fully understood by reference to four different kinds of causes: efficient (what brought the substance to be), material (what it’s made of), and, crucially, its final cause (final end or purpose) and formal cause (its essence, the principle of its growth and powers, what makes it the kind of substance that it is). With Protestant zeal, Bacon exhorted natural philosophers to, essentially, keep the efficient and material and jettison the final and formal. Set aside these theoretical, man-made “idols” and instead get back to real creation, he counseled. Conduct hands-on experiments, gather data, and induce generalizations from the evidence. Creation was to be piously cultivated for the good of all mankind, not held aloft in static, speculative contemplation for the select few. Bacon shows this system at work in his posthumously published New Atlantis, a utopian sketch of an island society that achieves astounding technological progress, from wonderful machines to vast extension of human life, through a hyper-specialized technocracy of statesmen-scientists.

Dramatic improvements in man’s estate have indeed followed Bacon’s program, though perhaps not in the way he expected. His ideas helped inspire the Royal Society, and Thomas Jefferson named Bacon one of the “three greatest men that have ever lived,” alongside John Locke and Isaac Newton. Others, however, have pilloried Bacon for improving material conditions while failing to solve the moral problem. In the mid-twentieth century, Marxists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, for example, blamed Bacon for unleashing the forces of instrumental reason and ego-driven domination that, when combined with his scientific program, ended in Auschwitz.

These critics have an elective affinity with contemporary anti-growth, apocalyptic techno-pessimists. If overdrawn, their criticism is helpful insofar as it shows that if we are to break out of stagnation, we have to transcend both the zero-growth mindset and the other-dominating, ego-asserting impulses of human nature. We can’t have real progress without real virtue.

To his credit, Bacon does offer a model for having both, but he doesn’t solve the moral problem through scientific research. In New Atlantis, what inspires the islanders’ efforts to better man’s estate is their knowledge of the highest reality — God — and they only become Christians in response to a revealed transcendent vision, when a beam of light from heaven appears offshore and they find a small wooden ark carrying the Gospel of Bartholomew. Setting aside the question of whether Bacon is authentically Christian or cryptically atheist, the crucial point is this: the story’s solution to the moral problem, as well as the key motivation behind Bacon’s program for technological progress, comes from exactly those transcendent realities that Murray failed to mention in the Natural History Museum.

What does this mean for people trying to cast a similar vision of technological and moral transcendence from inside the immanent frame? It’s partly thanks to the success of Bacon’s program that we are here: paying attention to empirical reality worked so well that we have more or less forgotten to pay attention to anything else, especially the moral and spiritual realities that go unseen. But if it’s Bacon’s rejection of Aristotle that helped bring us to this point, maybe it’s the recovery of Aristotle, in some sense, that can help us get beyond it.

Here are three ideas for what that could look like.

First, transhumanism has to come to terms with the body. Are we minds trapped in lifeless matter? Or are we bodies, composites of matter organized and actualized by an immaterial soul, the source of our mind and will, which is not just another gear in the material system but the principle that accounts for that system’s organization in the first place? Answers to these questions will determine at what point transhumanist technologies either advance or destroy the human person. Contemporary developments in cognitive science and trauma psychology, not to mention Aristotelian revivals in analytic philosophy, are showing how the mind and body are more intimately united than most transhumanists presuppose. But if being an embodied soul is a crucial aspect of what it means to be human, what trajectory ought our drive toward freedom and self-creation take? Where do we go with this desire to slip the surly bonds of matter? Just to Mars?

Second, perfection of human nature is not just physical. Aristotle in the Nicomachean Ethics describes “the human good” as the “activity of the soul in accord with virtue, and indeed with the best and most complete virtue,” all in the context of a full life. Can technology help us develop habits of temperance, prudence, justice, and fortitude? Or make us better receptacles for the gifts of faith, hope, and love? Technology may help us live forever, but can it make us saints? If we have followed the natural human drive to transcend human nature so far that we have figured out how to transcend death, but we haven’t figured out how to transcend the ego, we will end where C. S. Lewis warns we will end in The Abolition of Man: nature will win over itself, and all possibility of transcendence will be foreclosed — in a monosyllable: Hell.

Third, I would hazard that the only hope for avoiding such a fate comes from where Bacon found it: from outside history. To take one last cue from Aristotle, what seems to be missing is the proper object, or end, of this desire in human nature to transcend nature. Would not the rational response be to look outside nature to find it? What would “it” even be? Judging from the earlier parts of this essay, I suppose it would have to be some kind of grand meta-narrative that casts a comprehensive vision for moral and material progress, provides a practical program to realize that vision, grounds our demands for equality and human rights in an understanding of the human person as someone (not something) intrinsically valuable, implicates everyone, knits together body and soul, gathers up past and present and future, promises freedom for each person, redemption of all things, and a final transcendence into a life and world in and beyond this one — all ideally with an irresistible protagonist who sacrifices himself heroically for his friends and, against all odds, comes back to be with them again in the new world his love has made.

The specifications for such an adequate narrative are steep. Should we expect otherwise? Perhaps the only story that could meet all of them would involve something like the Transcendent Cause of all things becoming man so that man could transcend all things. But to be truly transcendent, the narrative would have to be spun in such a way that our human logic could only recognize it, not expect it — a divine comedy, as it were, that would keep us guessing until the end. If something like that had happened, of course, the world would never be the same. It would have to be “the greatest story ever told,” as even writers like Tom Holland, speaking as historians and not true believers, are coming to see.

But I suppose that such a story, if unfolded in all its metaphysical and historical dimensions, would be too overwhelming, or perhaps too uncomfortably real, to bring up on a stage-lit podium at a political conference or a carpeted basement full of conservative VIPs, even in a building named the Emmanuel Centre.

Where does that leave the dinosaurs in the “cathedral of nature,” who are trying to find a fitting final end for the human drive to transcend human nature in history, in humanist ideals of love, gratitude, and aspiration, or in whatever other reason we choose to get out of bed in the morning? The roar of the woke Leviathan might be the only answer we’ll get.

Or maybe we’ll find another one where Murray did, in C. S. Lewis. In 1954, fifteen years after his sermon in the University Church, Lewis left Oxford to accept a Chair in Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge. He called his inaugural address “De Descriptione Temporum,” a description of the times. In it, he speaks of the great divide that the Machine had rent between his own generation and the one that had grown up some twenty years later, after the First World War. This brave new world was now broken — atomized, mechanized, fractured across autonomous and subjectivist individuals, cut off from its spiritual roots. What would save us from being trapped in this machine? What can chisel the cracks in the immanent frame?

“To study the past does indeed liberate us from the present, from the idols of our own market-place,” Lewis answered, “but I think it liberates us from the past too” — rightly seeing the past frees us from our own misconstrued perceptions of it. As one of the few “natives” of the premodern world left in the modern university, and as one of the last spokesmen of the “Old Western Culture,” Lewis called himself a dinosaur. “Where I fail as a critic,” he concluded, “I may yet be useful as a specimen.”

A specimen, perhaps, or a witness. Living immersed in that “Old Western Culture” had turned Lewis from an atheist into the foremost Christian apologist of the twentieth century. One of the key moments leading up to his conversion came in September 1931, when his friend J. R. R. Tolkien took him for a walk around Magdalen College, Oxford, and told him the story of a God who died to save his people, a Myth who broke into history to become Fact.

Maybe following Lewis’s lead is what it means to do politics under Darwin’s shadow. And if being specimens can save us from the past and present, we can only hope it can help us rescue the future.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?