The substantial effort to produce science and journalism that move the locus of climate catastrophe well beyond what the data, models, or analysis can account for reflects a recognition that rapidly transforming the global energy economy in ways environmentalists have long called for is difficult to justify only on the grounds of precaution against highly uncertain future risks. “The public is unlikely to be spurred into action to combat global warming on the basis of scientific evidence alone,” participants at the 2012 Union of Concerned Scientists workshop concluded. “Climate change science is so complex that skeptics within the scientific community can create doubts in the public mind without any assistance from the fossil fuel industry or other climate change deniers.”

Did Exxon Make It Rain Today?

An essay in four parts

I. An Extreme Climate

II. Houses Upon the Sand

III. Selling the Story

IV. The Cost of Catastrophism

Yet there has never been much evidence that connecting extreme weather and natural disasters to climate change in this way would actually work to motivate action on climate change, and plenty of evidence that it wouldn’t. As early as 2000, a cognitive linguistics outfit called the FrameWorks Institute, hired by environmental NGOs to investigate new communications strategies to raise public concern about climate change, concluded that connecting climate change to extreme weather motivated adaptive and individualistic responses from the public, including, laughably, greater interest in purchasing an SUV, not collective demands for government action.

Since then, numerous studies have concluded that catastrophic messages about climate change tend to provoke fatalism, not activism. A 2009 paper, “Fear Won’t Do It,” for instance, found that “fear is generally an ineffective tool for motivating genuine personal engagement.” Another study, from 2010, “Apocalypse Soon?,” found that “dire messages warning of the severity of global warming and its presumed dangers can backfire, paradoxically increasing skepticism about global warming.” Even in the workshop convened by the Union of Concerned Scientists, public opinion experts warned that catastrophic messages and demonizing fossil fuel companies could backfire.

And that is exactly what has transpired over the last several decades. The issue remains near the bottom of public priorities in opinion surveys — it ranked 17th out of 21 in a recent Pew survey. Support for climate action waxes and wanes in a dynamic called thermostatic response, where public opinion is strongest in opposition to the party in power, meaning that support for climate action tends to be higher under Republican presidents than Democratic. With Democrats currently in charge, public support is again waning. Indeed, according to Gallup, which has conducted the longest-running survey of public opinion about climate change, public concern about global warming is marginally lower today than when Gallup first asked the question in 1989, with 61 percent now saying they are greatly or fairly worried about global warming, down from 63 percent then.

The main effects of efforts to move climate catastrophe into the present and blame it on fossil fuel companies have been to polarize the issue and induce paralyzing fatalism and anxiety, precisely as researchers long predicted. While public worry about climate change is no higher than it was when Al Gore sounded the alarm in An Inconvenient Truth, it is much more polarized, with Democrats more worried than they used to be and Republicans less so. The climate issue has become a permanent fixture in America’s long-running culture war.

Meanwhile, climate anxiety is rampant, particularly among the young. Climate scientists, activists, and journalists increasingly rage against climate “doomers” — people who believe that it is too late to save humanity. And a new generation of apocalyptic activists has now taken to vandalizing famous artworks and gluing themselves to roadways to block rush hour traffic in a misguided effort to get the public to wake up to what they insist is the looming threat of human extinction.

Despite this, the folk theory persists among much of the environmental cognoscenti that climate action requires that the public be convinced that a climate catastrophe is now unfolding, and that it is demonstrable in every extreme weather event. This theory of change is sustained, at bottom, not so much by strategic considerations as a foundational ideological commitment that is deeply embedded in modern environmentalist identity.

Sure, it may be difficult to find a large or determinative climate signal in extreme weather events. And the trends in terms of mortality and cost may point in a different direction. But the idea that human perturbations of the environment, even seemingly minor ones, could throw nature out of balance and lead to catastrophic consequences for human societies is as old as environmentalism itself, a thread running back at least to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and probably much further.

The logic of climate catastrophe follows this chain of reasoning exactly. The combustion of fossil fuels results in an increase in concentrations of a trace gas in the atmosphere, shifting the Earth’s energy balance and resulting in a degree or three or five of warming of the average temperature of the Earth, which in turn produces biblical plagues of floods, droughts, storms, heat waves, and rising seas. Calamity ensues.

The first several steps in this chain of logic, up to and including the warming of the Earth, are unquestionably true. But the plagues and calamity are not.

While warming will continue as long as the global economy emits greenhouse gases, most estimates today conclude that anthropogenic warming is likely to be substantially lower by the end of the century than estimates from as recently as a decade ago. In 2013, the mean end-of-century projection was 4 degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels, with many scientists assuming that the worst-case scenario of up to 5 degrees was also the most likely. Current estimates today top out around 3 degrees, while the worst-case scenarios suggesting significantly more warming are now widely understood to be highly unlikely.

But rather than update their priors in response to these facts, most environmental scientists, journalists, and advocates have simply shifted catastrophic claims from 5 degrees of warming to 3 degrees, the commitment to catastrophism being, at bottom, more epistemic than scientific. “A new climate reality: Less warming, but worse impacts on the planet,” proclaims a Washington Post piece from January 2023. “Yes, 3 degrees is far less nightmarish than 4 degrees. But it is immensely dangerous,” writes the New York Times.

Even among those who acknowledge that specific catastrophist claims are not particularly well supported scientifically, many believe them to be justifiable as a form of harm reduction.

But one need not look far to find all sorts of ways that this particular brand of harm reduction actually causes harm. Consider that some prominent leaders now propose limiting adaptation aid for developing countries to projects and activities that involve no fossil fuel use. “Financial institutions everywhere,” says United Nations Secretary General António Guterres, “must commit to end financing and investment in exploration for new oil and gas fields, and expansion of oil and gas reserves — investing instead in the just transition in the developing world.” This despite the clear adaptation benefits that fossil fuels offer poor countries and despite the fact that both rich countries and poor continue to depend on fossil energy for the vast majority of their energy needs. The topic became a sticking point at the U.N.’s recent climate conference. “The development of our countries depends, in fact, on the use of fossil fuels,” said Issifi Boureima, a Nigerian who is executive secretary of the Sahel Region Climate Commission.

Worse, a 2022 report by CARE International, “That’s Not New Money,” finds that international commitments from rich countries to increase support for climate mitigation and adaptation in poor countries have resulted in little overall increase in global aid but rather diversion of funding from proven development programs supporting health, education, and women’s rights. Meanwhile, a recent analysis by the Economist concluded that high energy costs across Europe during Russia’s war on Ukraine, driven in part by climate policies that increased the continent’s dependence on Russian gas, resulted in 68,000 excess deaths in the winter of 2022–23. And California, led by its powerful Air Resources Board and at the behest of its well-heeled environmental community, has implemented a wide range of regressive housing, land use, transportation, and energy policies that have raised living costs and limited opportunities for high-wage employment for its low-income residents.

Among those within the climate movement even willing to acknowledge these consequences, there has been little willingness to entertain the possibility that unfounded and exaggerated framings of catastrophic climate risk might have something to do with the promulgation of ill-conceived climate policies that often impose substantial costs upon those who are least responsible for emissions, and least able to pay the costs of the energy transition. But it is hard to conclude that the catastrophist claims of the climate movement, amplified through a media echo chamber, haven’t had something to do with the determination by ideologically aligned policymakers to undertake these efforts.

There has always been a compelling case for action to cut emissions and shift away from the use of fossil fuels that requires neither prophesying human extinction nor insisting that every extreme weather event is now brought to you by Exxon. Consider that indoor and outdoor air pollution, largely due to combustion of fuels for heating, cooking, power generation, transportation, and industry, results in between 7 and 9 million premature deaths a year. A temperate climate, moreover, is clearly a desirable objective to pursue, even given that humans are likely capable of adapting to climate change reasonably effectively. Just because air conditioning and other measures can allow large human populations to live in places like Phoenix and Riyadh as they become hotter doesn’t mean we shouldn’t attempt to limit how hot those places will become.

There is also the small matter of the rest of creation, the riot of life on Earth that has not been bred, modified, or otherwise gang-pressed into serving human material needs. Many of the Earth’s ecosystems and much of its biodiversity will not be able to adapt to a significantly warmer climate, particularly because humans have commandeered so much of the terrestrial surface for agriculture, cities, roads, mining, and other activities, fragmenting the habitat that remains for other life forms.

These garden-variety environmental considerations, along with non-environmental objectives such as cheap, abundant, and reliable energy, remain substantially higher public priorities than climate change in most opinion surveys. But these concerns also fail to provide much justification for the sweeping demands of the climate movement. Apocalyptic claims about an unfolding emergency, rather, serve a millenarian agenda that variously demands that we abolish capitalism, bring about an end to economic growth, power the global economy entirely with wind and solar energy, feed the global population only with small-scale organic agriculture, and cut global emissions in half over the next decade or two.

Against these claims, which insist catastrophe looms absent radical action, the actual trajectory of the global economy is quite different. Global emissions appear to be close to peaking, even as energy demand continues to rise rapidly in many poor and middle-income countries, which increasingly meet that demand through a combination of more-efficient end-use technologies, renewables, nuclear power, and lower-carbon natural gas instead of coal.

Meanwhile, in the developed world, emissions have significantly fallen over the last several decades as population growth slows, economic growth shifts toward less-carbon-intensive knowledge and service sectors, and cleaner technology replaces dirty. Carbon emissions in the United States in 2022 were 17 percent below their 2007 peak and are now lower than they were in 1989. The United Kingdom’s emissions, which kicked off the long rise in global emissions at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, are now lower than they were a century ago. Simply assuming continuing incremental improvements in technology and policy, one recent paper in Environmental Research Letters finds that the world could achieve net zero emissions and stabilize the climate at just over 2 degrees, the long-time international target for stabilizing emissions, by the end of this century. Achieving net zero and stabilizing the climate could happen somewhat faster or slower. But not that much faster or slower. The study analyzed a range of plausible scenarios produced by the IPCC and concluded that none resulted in over 3 degrees of warming, with most resulting in less than 2.5 degrees.

That is a world in which the economic cost of all disasters will continue to rise, simply because there is more wealth for those events to damage. More importantly, that increasingly prosperous and technological world will likely continue to see falling mortality rates from climate-related disasters, even as some types of extreme weather do intensify.

Taken together, these factors paint a far different picture than the dire warnings of doom that dominate most news coverage of climate change, environmental advocacy materials, and grandstanding speeches by world leaders at U.N. climate conferences such as the recent summit in Dubai. There is little evidence that climate change has, or is in imminent danger of, tipping the world into a new state of imbalance in which a raging climate threatens the survival of the human species or societal collapse. The world, rather, has made real progress to both limit warming and adapt to the climate we actually live in.

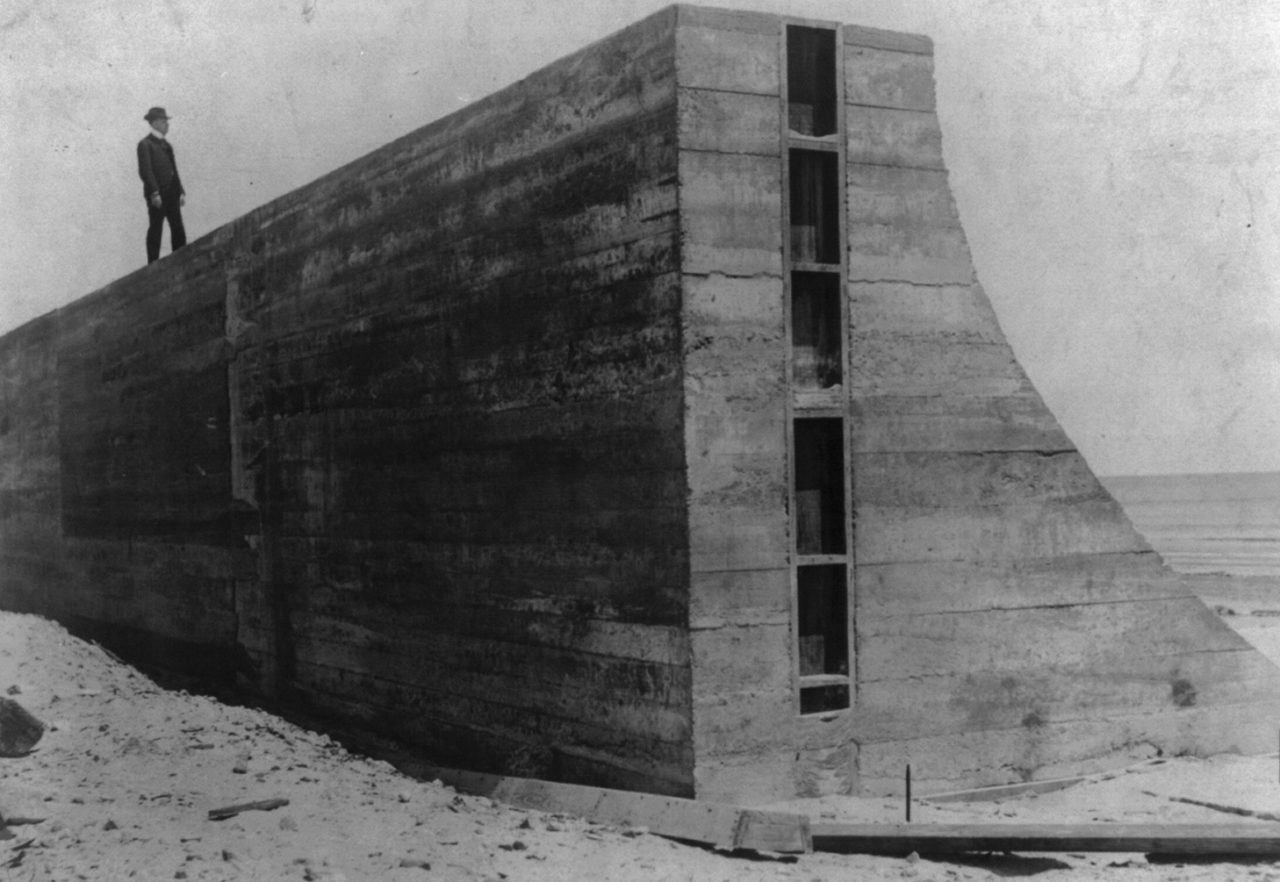

Galveston itself offers a useful lesson in renewal and resilience. In the years after the Great Hurricane of 1900, the city rebuilt. Over time, it has raised the elevation of some parts of the city by more than 10 feet, built a seawall to protect it from storm surges, and replenished its sand dunes. Those were costly projects, built by a community that was far poorer than it is now. Yet today, Galveston is a thriving city, with a 40 percent larger population than lived there in 1900.

In the century since the Great Hurricane, the city has been regularly hit by strong hurricanes. But none has resulted in more than a few dozen fatalities. And while every death from a natural disaster is a tragedy, Galveston’s story is a profoundly hopeful one. It is also a story not remotely limited to Galveston, one that is playing out all over the world, as modernizing societies, rich and poor, have deployed technology and infrastructure to tame the impact of extreme weather.

Galveston reminds us that while the climate is still warming, human societies have always had to contend with dangerous weather. We know how to increase resilience to climate extremes. We also know how to reduce emissions — many nations have been doing so for decades. Cutting emissions and adapting to a warming climate requires neither bombarding the public with apocalyptic threats nor imposing arbitrary targets and deadlines for the elimination of all fossil energy. Rather, it requires doubling down on the things that we already know work: modernization, adaptation, innovation, and technological change.

← Return to Part I of the essay.

Or read a printer-friendly version of the entire article.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?