Each year, Munich Re, the global reinsurance colossus, releases damage estimates of the total cost of natural disasters around the world. Decade over decade, that cost has risen, to over $200 billion annually in recent years. Between 1990 and 2017, the global cost of weather-related disasters increased by 74 percent, according to an analysis of this data by University of Colorado professor Roger Pielke, Jr. Media accounts frequently suggest that the increase in billion-dollar weather disasters in the United States is due to climate change, as does the Biden administration.

Did Exxon Make It Rain Today?

An essay in four parts

I. An Extreme Climate

II. Houses Upon the Sand

III. Selling the Story

IV. The Cost of Catastrophism

But if climate change is behind the increasing cost of natural disasters, then you would expect that the cost of disasters related to weather would be rising faster than that of disasters not related to weather. Nobody, after all, suggests that climate change is resulting in more severe earthquakes or more frequent volcanic eruptions. Instead, the opposite is true. The cost of disasters unrelated to weather increased 182 percent between 1990 and 2017, more than twice as fast as for weather-related disasters.

In truth, it is economic growth, not climate change, that is driving the boom in economic damage from both weather-related and non-weather-related natural disasters. All over the world, there is far more wealth in harm’s way that can be damaged by natural disasters.

Consider the familiar and oft-cited example of hurricanes hitting the United States. Year to year, the number and severity of storms that make landfall in the North Atlantic basin, and particularly in Florida, will largely determine whether extreme weather costs increase or decrease for the whole world. Florida has regularly been hit by strong hurricanes over the last 75 years, and the costs of those hurricanes have increased massively. But the reason that those costs have increased so much is because the state’s population and wealth have grown enormously. The population of Miami-Dade County alone, where a large share of the state’s disaster-exposed wealth is located, has risen from a bit less than 500,000 in 1950 to 2.8 million today. Per capita income data for the county from an economic database provided by the Federal Reserve System only go back to 1969, but even over that period, it has risen from around $4,000 per person to over $68,000 today. Taken together, the enormous increase in population and wealth in the region drowns out any identifiable economic signal from climate change. With or without climate change, the economic cost of hurricanes in Florida would be vastly higher now than in the past.

This dynamic, called “exposure” by those who study disaster risk, dominates the economics of virtually every kind of climate-related disaster. When the Munich Re data is calculated as a percentage of GDP rather than simply looking at the increase in the absolute costs of extreme weather, global damages resulting from extreme weather have actually fallen since 1990. And that doesn’t fully reflect the degree to which increased wealth exposed to extreme weather in places like Miami dominates global economic costs of disasters. Since 1950, accelerating urbanization has resulted in an enormous shift of the global population, economic activity, and wealth into coastal regions, river floodplains, and other regions that are most exposed to climate-related hazards. These agglomeration effects, as economists call them, mean that the increase in population and wealth in these regions has significantly outpaced the already unprecedented rate of economic growth globally since 1950.

The relationship between climate change, extreme weather, and disaster costs is further complicated by another important factor that determines how human societies are affected by climate extremes. Things like stricter building codes, hard and soft infrastructure, better technology, and a range of other factors make people and property far more resilient to the weather. Disaster risk experts call this factor “vulnerability.” And vulnerability to extreme weather has been falling significantly all over the world for many decades.

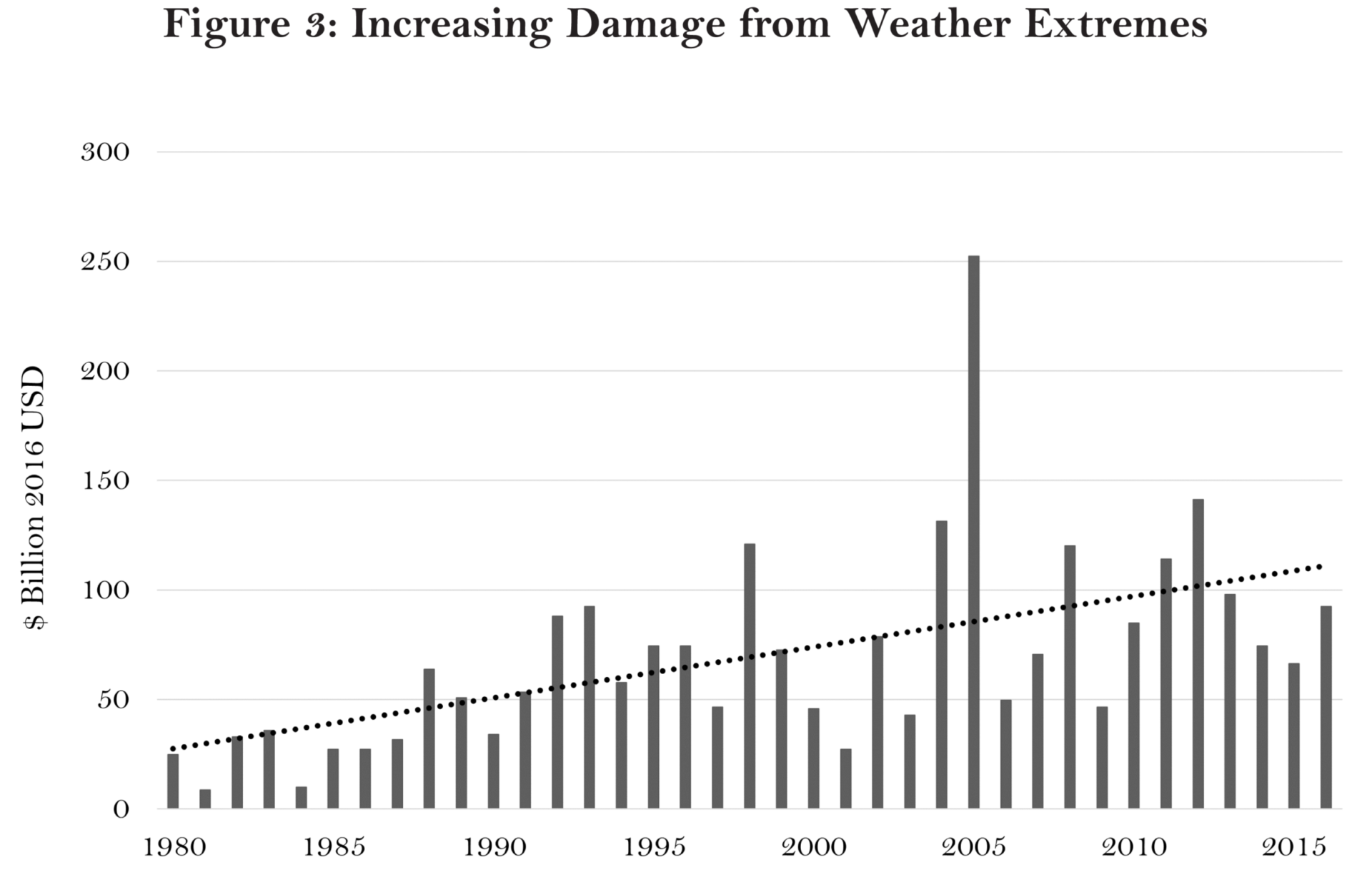

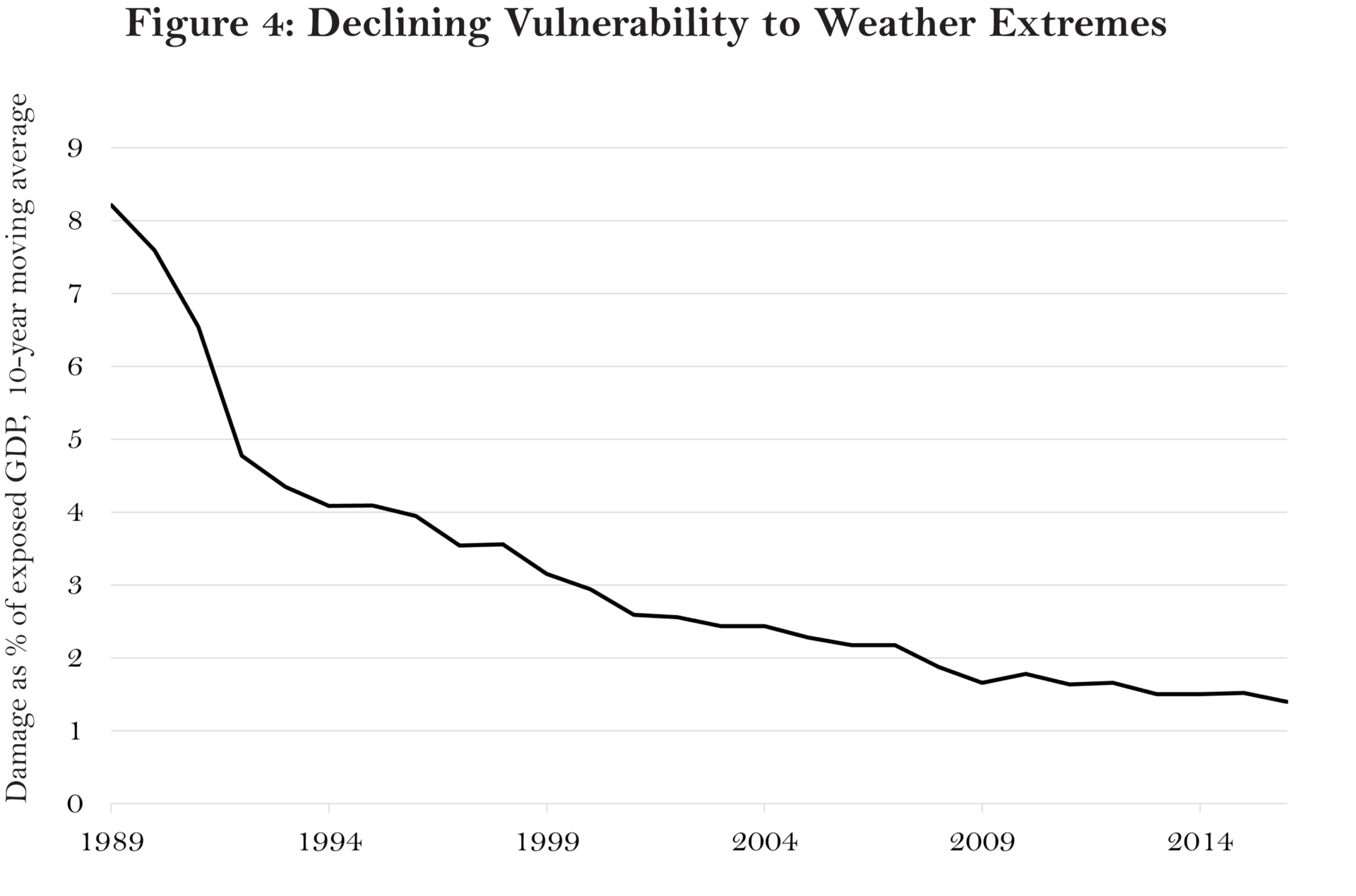

While trends in exposure are increasing the costs of weather-related disasters, trends in vulnerability are reducing those costs. Between 1980 and 2016, according to an analysis of Munich Re’s data by researchers Giuseppe Formetta and Luc Feyen, global losses from weather disasters ballooned by $2.6 billion per year, due to the growth in economic activity that was exposed to those disasters. But losses as a share of the economic activity in exposed areas shrank by a factor of more than four (See Figures 3 and 4.) In the 1980s, when climate-related disasters struck, the average cost of the damage within 250 miles of the disaster was 8 percent of the GDP produced within the same area. By 2016, that figure had fallen to less than 2 percent. Because of economic growth and agglomeration effects, there was much more economic activity in harm’s way. But because wealthier societies have greater resources to put toward climate resilience, that wealth also became much less vulnerable to extreme weather.

Once you account for increased exposure and reduced vulnerability — or “normalize” for these factors, as researchers call it — there is next to no evidence that climate change has increased the costs of weather disasters anywhere. A comprehensive analysis of 54 different studies of these cost trends, “Economic ‘normalisation’ of disaster losses 1998–2020: a literature review and assessment,” also authored by Roger Pielke, found that only one of those studies showed increasing costs from weather damage that could be attributed to climate change.

Vulnerability has an even greater influence on the human costs of extreme weather than on the economic costs. While a strong hurricane making landfall in a rich country will have a far greater economic cost than in a poor country, because there is so much more wealth exposed to the hurricane, the same hurricane will have a far greater human cost in the poor country, measured by deaths and injuries. Take the real-life example of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The two Caribbean nations share the same island. Each nation has a population of around 11 million people. The Dominican Republic is not a rich nation. But its per capita income is about six times greater than Haiti’s.

In 2004, Hurricane Jeanne made landfall on the eastern tip of the Dominican Republic as a Category 1 hurricane, demonstrating the extraordinary influence that vulnerability has on the human costs of natural disasters, with tragic consequences for Haiti. By the time the storm had crossed the island and reached Haiti, it had been downgraded to a tropical depression. Still, it killed over 3,000 people in Haiti and only 19 in the Dominican Republic.

The difference in the human cost of Hurricane Jeanne in Haiti and the Dominican Republic demonstrates that poverty and weather extremes are a deadly mix. Thankfully, increasing wealth, infrastructure, technology, and public services have massively reduced vulnerability to extreme weather and natural disasters over the last century. Even as the global population has risen from less than 2 billion people in the 1920s to 8 billion today, deaths from climate-related disasters have fallen dramatically, from around 500,000 annually then to 30,000 now. Measured on a per capita basis, climate-related mortality has fallen by a factor of more than fifty. These comparisons flatter the past. There is a strong reporting bias toward the present, since most parts of the world didn’t reliably track disasters and their consequences until relatively recently, meaning that actual climate-related mortality in the first half of the twentieth century was almost certainly far higher than available data suggests.

Vulnerability, moreover, is falling fastest in poor countries. Formetta and Feyen find that poor countries have seen much greater reduction in climate vulnerability than rich countries since the 1980s. As the resilience of poor countries has improved, the vulnerability gap between rich and poor countries has dramatically narrowed.

None of this evidence should be taken as suggesting that climate change is not happening and is not having some impact on weather, disasters, and the consequences that they bring to human societies. But if human society is currently in the midst of a climate emergency, as many people now believe, there is little measurable evidence thus far that it is an emergency of dollars or lives lost.

→ Continue to Part III of the essay.

Or read a printer-friendly version of the entire article.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?