A response to “How to Fix Social Media” by Nicholas Carr

Anyone who is even mildly worked up about the future of digital technology has likely been cornered at some party by a blithe disciple of Poor Richard’s Almanack who, full of glad tidings, insists through mouthfuls of baby quiche and salmon canapé that the invention of TV worked out okay, or the invention of the printing press worked out okay, or the invention of writing worked out okay, so this here beeswax will too. (Did they, though? But let it go; that way’s madness.) Arguing about these historical parallels is, at best, like arguing about the limits of a metaphor, and approximately as frustrating. Some things are kind of the same, others are sort of different, so that, if one hopes to disagree, one is placed in the embarrassingly petty-minded position of claiming that “tomato” is really pretty different from “tomahto,” that the parallel eclipses some things as much as it may illuminate others.

At worst, though, such parallels can be exercises in false reassurance. They artificially blunt the edges of our current problems by suggesting that we find ourselves in a “replay” of past dynamics, which were, eventually and through a spirited exchange of views, sorted out. (The adjectives “messy” and “complicated” make a predictable cameo here, as if to say: “Relax! We were here once before.”) Let us earnestly hope so. In the meantime, while Nicholas Carr is hardly notorious for his rosy outlook on matters digital (having singlehandedly jump-started contemporary tech-skepticism), his case for fixing social media offers just this kind of false reassurance. Not only will his ideas not help to fix social media, but the terms of his analysis refuse to reckon with the danger in its magnitude.

The bulk of Carr’s article traces the history of the “two-pronged philosophy” governing electronic communications for much of the twentieth century: the “secrecy of correspondence” doctrine (whereby personal messages are accorded formal privacy protections) and the “public interest standard” (whereby some standard of the common good governs what is legally admissible public speech). What’s most interesting about Carr’s account is the elaboration of the point that our notions of privacy and publicity are themselves technology-specific. (One might add that the very notion of a “right to privacy” was first formulated in response to the advent of photography and other forms of mechanical reproduction.) It’s also helpful to see how and why government legislation on such matters necessarily lags behind technological development; it takes time for the implications of any given invention, intended and unintended, to fully express themselves.

But as a premise for the legislation of social media, the two-pronged distinction is a bad miss. While “secrecy of correspondence” is a principle that undoubtedly depends on the presence of the mail system, one cannot assume that it is directly applicable to digital communication, as his own point about media-specificity implies. Carr claims that “at a human level” we can still make sense of social media by analyzing it into its private and public uses. But social media thrives on confounding this distinction. The presumption that you are privately “sharing” when you publicly post a curated image of your turnt night out or of your corgi in costume, the alone-togetherness of it, is the whole point. Can we assume that an Instagrammer with a measly hundred followers is engaged in “conversation” with them, as Carr suggests? (Can one converse in Instagram stories?) Yet it’s not even the number that matters, so much as the fact that social media is a witches’ brew of privacy and publicity: not just the one layered on the other, but a new chimera entirely. It is because I can communicate with others noncommittally in this way, because I just might go viral, because I can project a persona of what I think and who I am, because I am exhibiting myself as content and as “brand” rather than taking the trouble to articulate my views to someone in particular, that the whole racket is such a blast. If Carr is right that social media can sometimes be understood to have a strictly private function, then there’s no strong reason why in those cases it shouldn’t be interchangeable with email. But to resolve social media into the components “private” and “public” is like explaining Grand Theft Auto as a combination of TV cartoons and the game of “tag” — a Procrustean stretch that mutilates the phenomenon in order to explain it away.

Carr likewise proposes sharply restricting how social media companies use our data. This seems like a sensible idea. Some version of what is touted under the (undignified) name of “data dignity” continues to gain traction — perhaps a scheme in which we are paid for the commercial uses of our data, or stricter procedures about opting in or out, on the model of EU regulations. Tech is an attention-extraction industry: by gathering and aggregating our information, many companies are getting something for nothing. But they are also providing services that most of us seem unwilling to shell out for (like email, search engines, and social media), and these services only improve themselves by becoming more convenient.

Behold the rub. An app that only used a given user’s data on a “closed loop,” as Carr suggests, would be inept. Alexa would not have enough data to make handy predictions of any kind about what we are searching for, what we are typing, what we are buying. Predictive services are convenient precisely to the degree that they can typify and extrapolate from our input; working off of just my data or yours, they would be worse than useless. There is, in this sense, a direct tradeoff between privacy and convenience. Do Americans truly value privacy, as the surveys indicate? We sure have a funny way of showing it. (When was the last time any of us bothered to read the “terms and conditions” from A to Z? Or the last time we refrained from using social media out of privacy concerns?) Nor do digital natives seem to have the same visceral reaction as analog fogies who strongly associate the notion of privacy with file cabinets and papers stuffed under mattresses. Facebook has, of all companies, attracted the most public scorn for its share of data-sharing scandals in the past few years; even so, its user numbers have steadily continued to increase throughout that time. If it’s lost users to Instagram, it’s because the Boomers have spoiled the party by joining it, not because of privacy concerns. Both are Meta, in any case — there is no alternative.

As to the public prong of the issue, Carr concedes that here’s where it gets “more complicated.” (Ahem.) I think many of us can agree that legislation is needed to censor some social media content — so many of us, in fact, that it’s not really clear who stands in the way. Carr makes a sapient nod toward “many powerful private interests.” But who are they? It’s not social media companies. Mark Zuckerberg has long called for speech legislation. Meta’s glossy new ad campaign reiterates Carr’s very point about legislation lagging behind technology. Jack Dorsey is cagier, but he certainly got his knickers all in a twist about having to ban a sitting president of the United States. Regardless of their explicit statements, both of their companies have seemed desperate not to have to (in fact) legislate speech all on their own. Nor is it really clear why it’s in their commercial interest to do so; the moderation of politically flammable content is obnoxious to some large portion of their customers. They have become umpires only by default; they call the shots over whole no-man’s-lands of speech into which no legitimate authority particularly wants to tread. But to the extent that there is opposition to speech legislation on social media, it is not because there is disagreement that the major platforms are cesspools of lies (by which I mean other people’s lies), but because we don’t believe that there could be any impartial standard by which to fairly adjudicate them.

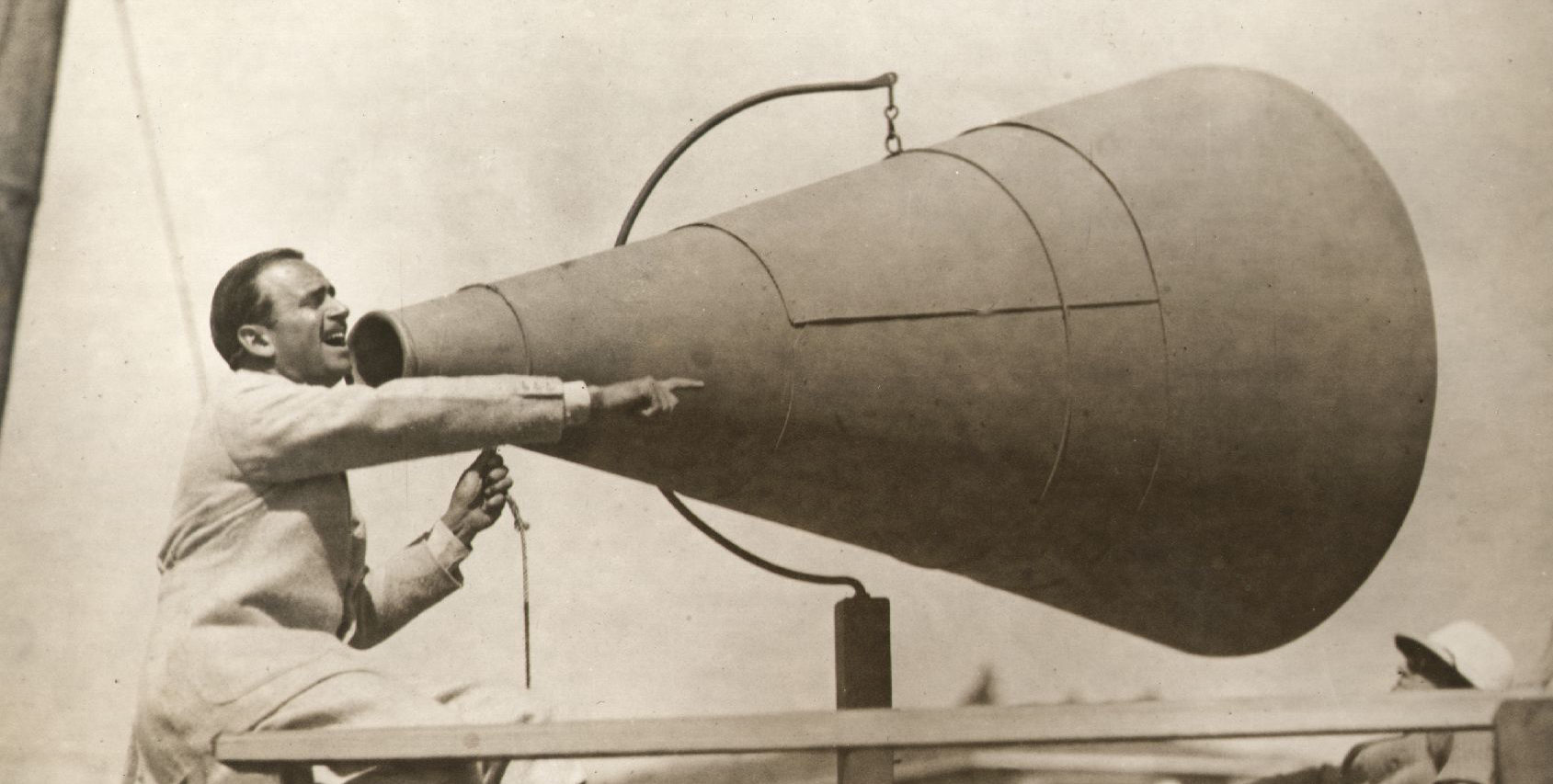

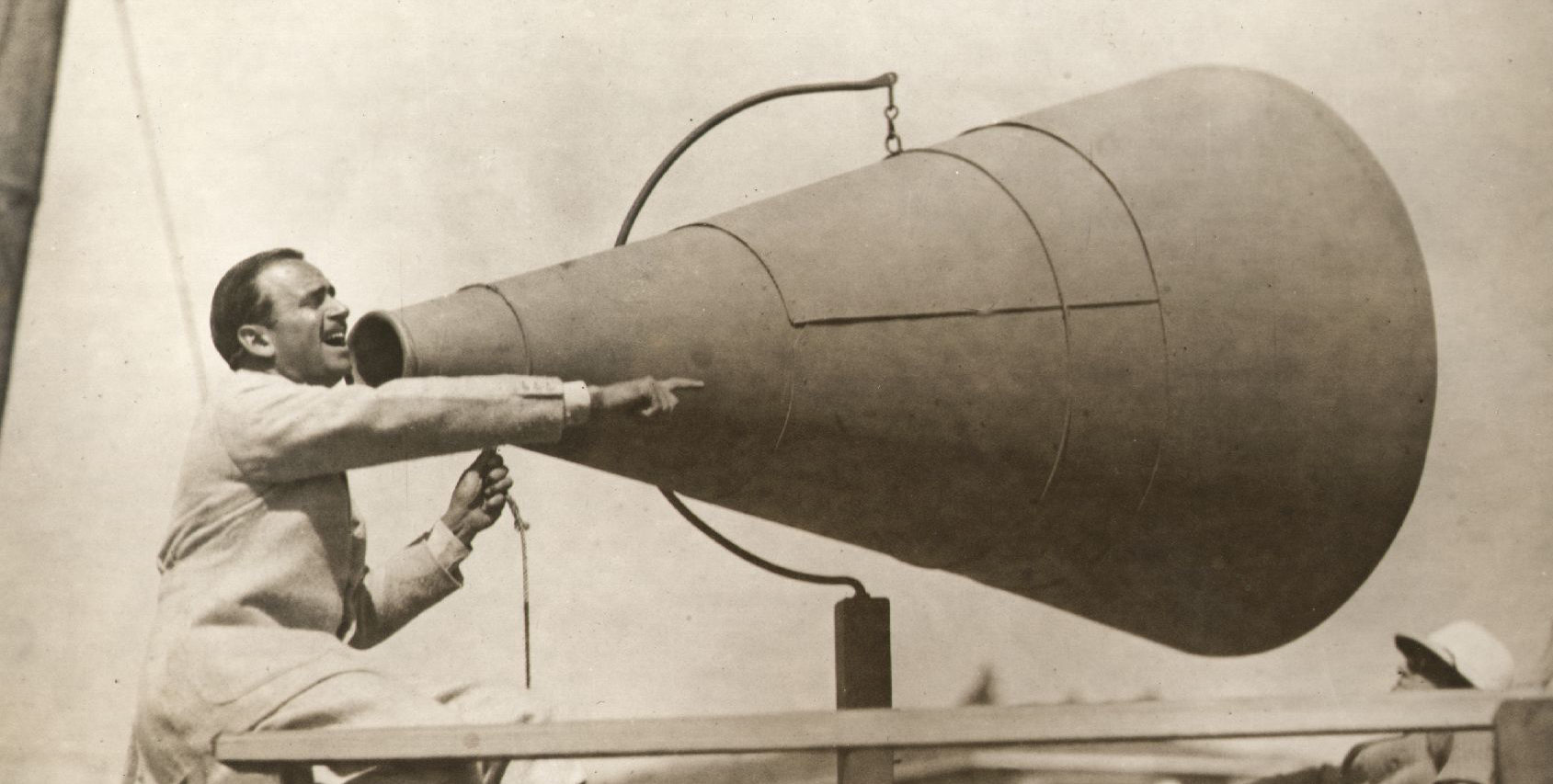

What would Carr’s “public interest standard” look like now? (Whose interest? Which public?) There have long been some tin-hatters who, as Carr points out, could be singled out for censorship. This was not simply because of some objective measure of their falsehoods, but because there was a mainstream center powerful enough to sustain the sense of difference between exception and norm. The flexibility that Carr rightly points to as a benefit of this standard was a consequence of being able to meaningfully make that distinction. This sense of mainstream norm was itself reinforced by the fact that television and radio were broadcast from largely centralized channels; a limited number of broadcasters, operating within a local or national radius, were responsible for most programmed content. Social media giants, on the other hand, are organs of international speech in which every single user is a broadcaster. They are norm-disrupting rather than norm-constituting, because the wild scramble for our attention tends to render most salient what is easy, outrageous, weird, and otherwise brain-baiting, rather than what is moderate, balanced, generous, and soul-freeing. (This is why we can’t have nice things anymore.)

Are there any standing authorities on climate change, election results, or vaccine data, such as could command more widespread credibility than Facebook’s own efforts at content moderation? The issue is not simply that people are misinformed (the technocrat’s fond hope), but that digital information has allowed us to define our political commitments through pledging allegiance to divergent facts. The question of who won the 2020 election isn’t so much a matter of ascertaining and disseminating the truth — no one is in any doubt about who won — as it is a matter of affirming our political standing. Social media has helped unravel the very possibility of identifying the public interest or the “will of the people” in a way that could be widely regarded as legitimate. There is no norm left to judge these questions. We have a basic disagreement in this country not just about “values” but about how to call a fact a fact. Any legislation along the lines proposed by Carr would therefore be one that half of the country would not only regard as coercive, but would have a defining partisan stake in regarding as coercive.

To suppose that this is all fixable is wishful, it is to trick ourselves into thinking that we can exercise greater control over things than we really can — a tranquilizer that lulls us back to sleep from the terrible deterioration of our political life. Social media is not a medium that we can ever legislate for responsible use, any more than an Uzi can be part of our picture of responsible gun ownership or a Jägerbomb part of our picture of responsible drinking. To say that some people do use it responsibly is no rejoinder — one can of course ride to hounds with an Uzi or sip a Jägerbomb at a genteel soirée.

The immanent logic of social media is at harsh odds with the norms that undergirded our earlier principles of speech. In particular, the distinction between public and private that Carr identifies is a version of the classical liberal boundary between the public square and private conscience, such that the merits of ideas might be debated impartially for the common good and regardless of the creeds of the participants. Social media, by contrast, places one’s identity squarely at the center of communication, making speech inseparable from it. To censor content is unavoidably to cancel people. So here’s my proposal: liberal democracy or social media — let’s pick one. We’re doing it anyhow.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?