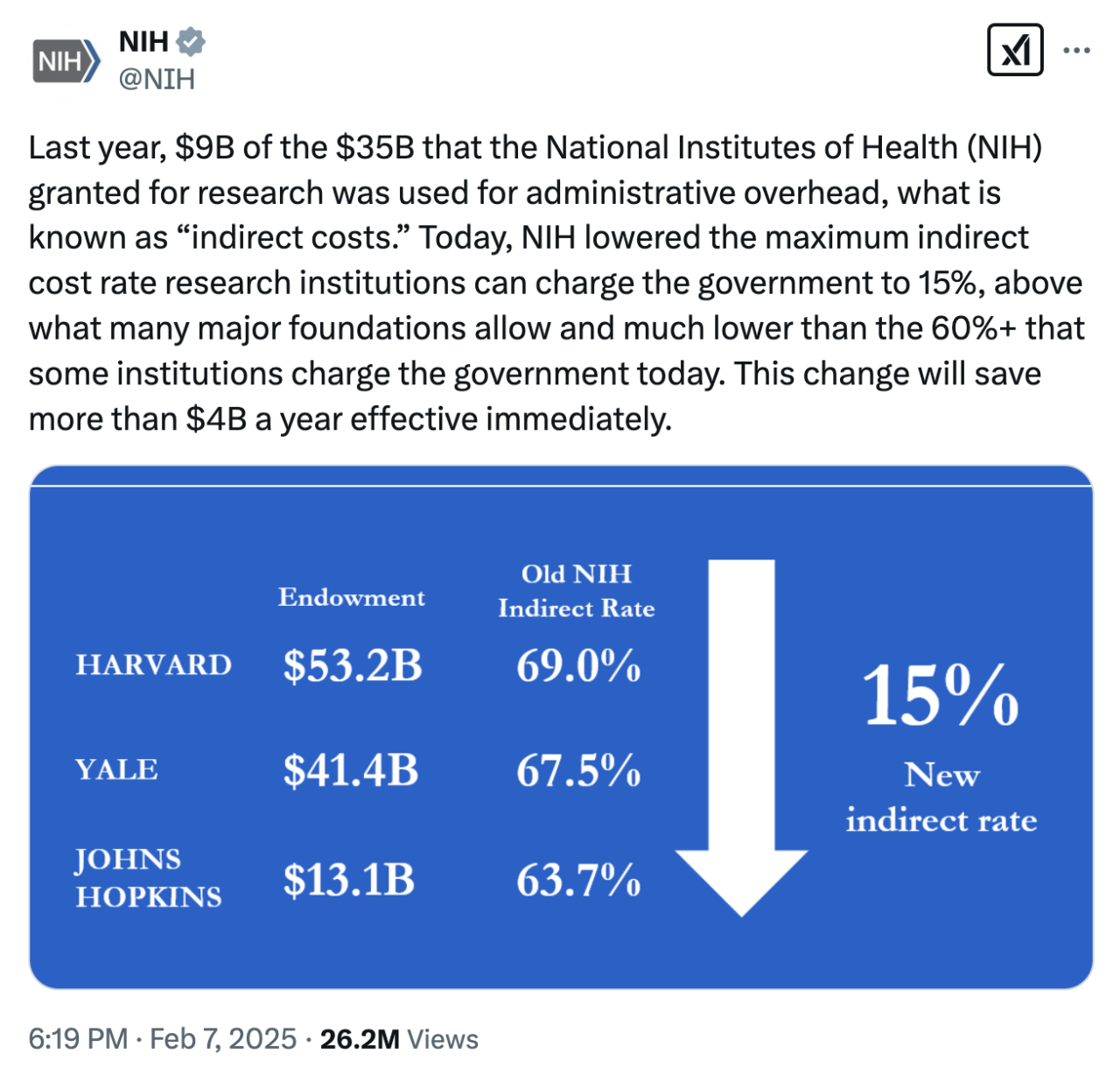

Last week, in a classic Friday evening news dump, the Trump administration set off one of those frantic controversies that seem to be our fate for the next few years. A tweet from the official X account of the National Institutes of Health declared:

The tweet was backed up by a more formal memo justifying the new policy on the grounds that private foundations insist on much lower overhead rates in their grants to universities than the government does.

The response was predictably swift and intense. Scientists and advocates accused the administration of betraying patients and surrendering America’s leading position in biotechnology and medical research. Trump allies, from Elon Musk on down, answered them by calling elite universities spoiled, corrupt, and profligate:

Everyone involved knew their roles in this drama by heart, and fell right into them with gusto.

But the familiar partisan script obscures a deeper problem. Lost in the rush on all sides to play right into one another’s crudest clichés was an opportunity to actually govern a little better. On this front, as on many others, Donald Trump’s election has created real opportunities for advancing needed change. But the new administration seems intent on squandering those opportunities because it does not see itself as responsible for the federal government. Eager to demonstrate how corrupt our institutions have become rather than to facilitate their improvement, it is opting for lawless and performative iconoclasm over the more mundane but potentially transformative work of governance.

Indirect costs in NIH grants are a perfectly reasonable target for reform. But such reform could only succeed if it takes account of the law and if it gives Congress, the NIH itself, and the community of academic researchers some room to adjust to the administration’s new demands and priorities. That’s what effective executive leadership would look like.

The division of federal research grants into direct and indirect funding stretches back many decades, and is rooted in the nature of academic research. Scientists in universities rely on labs, equipment, support staff, and facilities that are not created for any one project, and so can’t be justified as part of the direct research costs involved in a specific funded grant. Rather than asking scientists to calculate their portions of these overall costs, the federal R&D apparatus has let researchers apply for support just for their individual substantive projects while calculating the appropriate overhead rates through a negotiation with the larger academic institution that employs them.

That rate differs from one academic institution to another, as facilities, labor, and other costs vary in different parts of the country, and different universities are run in different ways that affect their infrastructure and overhead spending. The rate for each university is set by a negotiation between that institution and the Department of Health and Human Services, and is renegotiated every few years. The negotiated rate is then applied as an addition to an approved NIH grant.

So, for instance, if a research team is approved for a $100,000 grant at a university that has a 50 percent indirect-cost rate, the NIH will give the university a $150,000 grant. The university is not “siphoning off” the indirect cost from the research money, as Elon Musk claimed, but getting it in addition. That way, research grants can be awarded on the basis of a project’s substantive scientific promise and material needs, and the different infrastructure and overhead costs of different institutions don’t distort that judgment.

The complexity of this negotiating process, and the dramatic differences in indirect-cost rates between universities, has long drawn the attention of critics and reformers, and the formula has been adjusted in various ways over the years, under administrations of both parties. The notion of a flat rate is nothing new, and the incentives for cost-savings that it might create could well be good for many research universities. So what the Trump administration has in mind could be pursued in a way that would save money and improve the American medical-research enterprise while minimizing disruption and uncertainty among academic researchers.

If they wanted to, Trump’s NIH officials could have told grant recipients that these procedures would be reviewed this year and they should prepare for a change. They could have put in place a gradual adjustment in the direction of flat indirect-cost rates over several years, to let institutions adjust or propose a plausible set rate. They could have invited ideas from the field about how overhead could be funded differently. They could have made clear that they want to strengthen NIH’s ability to support promising research and that rethinking indirect-cost rates could free up funds for direct research spending. That’s how administrators who value the steadiness and effectiveness of the institutions they administer would go about such a change.

But that is not how the Trump administration has gone about it. Rather than pursue this idea as a way to improve the institution they’re administering, they have chosen to pursue it as a way to attack that institution — ridiculing its existing practice and practitioners, announcing a dramatic policy change on a Friday evening that is set to take effect the following Monday, and presenting the move in a way intended to maximize surprise and invite stiff opposition.

They’ve even made this move before their newly nominated NIH director has been confirmed for the job, putting him in a challenging spot at his confirmation hearing in a way sure to make for high drama and to force him to embrace a contentious policy change that he has not been permitted to shape. Rather than take this new direction in a way that might reinforce the NIH’s promise and strengths, they have opted to do it in a way that can only be understood as undercutting it.

This approach is characteristic of how the Trump administration has taken on its work so far in this new term. It is evident in controversies over USAID, civil-service reforms, and more. In each case, there is room for serious change, but the administration has chosen an approach that leaves no room for conciliation and adjustment, and so for durable improvement.

And as in those other controversies, this latest move at NIH has also involved pursuing goals that were sought without success in Trump’s first term, but in ways that are only more oppositional and less lawful this time.

That may be the strangest facet of this particular controversy. In its 2018 budget submission to Congress, the Trump administration proposed a reform of indirect-cost rates at NIH almost identical to the one announced last Friday. That proposal would have taken down rates to 10 percent, and Trump’s budget that year assumed a savings of $4.6 billion, almost exactly the same as what the NIH says would be saved under its new approach.

Both houses of Congress were controlled by Republicans in 2018, and those Republicans considered the administration’s idea and flatly rejected it. In fact, both of the relevant appropriations committees went out of their way to not only dismiss but sharply critique the proposal. In its committee report, the Senate Appropriations Committee noted:

The methodology for negotiating indirect costs has been in place since 1965, and rates have remained largely stable across NIH grantees for decades. The Administration’s proposal would radically change the nature of the Federal Government’s relationship with the research community, abandoning the Government’s long-established responsibility for underwriting much of the Nation’s research infrastructure, and jeopardizing biomedical research nationwide. The Committee has not seen any details of the proposal that might explain how it could be accomplished without throwing research programs across the country into disarray.

The House Appropriations Committee, in its own committee report, went further:

While the Committee appreciates the Secretary’s efforts to find efficiencies in NIH research spending, the Administration’s proposal to drastically reduce and cap reimbursement of facilities and administrative (F&A) costs to research institutions is misguided and would have a devastating impact on biomedical research across the country. To ensure that NIH can continue supporting both direct and F&A costs as is their current practice, the bill includes a new general provision directing NIH to continue reimbursing institutions for F&A costs according to the rules and procedures described in 45 CFR 75 (with the exception of existing waivers for training grants).

Notice that last part. The Congress didn’t just reject the Trump administration’s proposal. Because they were concerned that the existing regulatory language might allow the administration to change indirect-cost rates on its own, they inserted into the appropriations bill specific language to prohibit the administration from doing that.

That language has been in each HHS appropriations bill since 2018. In the 2024 bill that is still in effect today, it reads:

In making Federal financial assistance, the provisions relating to indirect costs in part 75 of title 45, Code of Federal Regulations, including with respect to the approval of deviations from negotiated rates, shall continue to apply to the National Institutes of Health to the same extent and in the same manner as such provisions were applied in the third quarter of fiscal year 2017. None of the funds appropriated in this or prior Acts or otherwise made available to the Department of Health and Human Services or to any department or agency may be used to develop or implement a modified approach to such provisions, or to intentionally or substantially expand the fiscal effect of the approval of such deviations from negotiated rates beyond the proportional effect of such approvals in such quarter.

This means that what the NIH announced it was doing last Friday is probably illegal. In its policy memo, the agency didn’t even try to justify its action in light of this provision of law. The memo claimed to draw its authority entirely from the underlying regulatory language in part 75 of title 45, even though this law prevents the administration from using that authority in the way it now proposes.

Maybe the NIH’s lawyers have some plan for how they can justify doing exactly what the law tells them they can’t. Maybe the administration wants the fight and doesn’t care if it loses. Maybe they plan some legal challenge to the spending provision.

Maybe. But it sure seems more likely that in this domain, as in others, the Trump administration has decided to grandstand rather than govern. They have taken an idea that could easily have been the foundation for a plausible reform and have chosen instead to make it the foundation for a social-media campaign divorced from administrative realities, at odds with the law, likely to be reversed, and sure to further raise the temperature of our politics.

Such a result would not be understood as a failure by the people pursuing this strategy. It appears to be their goal. And that’s the problem that Friday’s announcement highlights. The new administration seems not to think of itself as charged with governing.

This relatively modest controversy at the NIH therefore offers a kind of microcosm of the larger dynamic of this moment. At the root of the contempt in which Donald Trump and his team hold many of the core institutions of our society is not how they view those various other actors but how they view themselves. The president and those around him appear to understand themselves as outsiders fighting the government, not as insiders running it. That poses real dangers for our system of government, but also for them. It means that their displays of strength reveal their weaknesses, and it points to serious questions about whether much of what they have begun in recent weeks can really succeed and endure — and about whether their definition of success will ultimately be shared by the public.

A fight over indirect costs in research grants won’t settle all of that. But administration comes down to mundane details, and small instances can illuminate large trends.

Keep reading our Spring 2025 issue

How gain-of-function lost • Will AI be alive? • How water works • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?