If you study air and space disasters, you will notice a recurring pattern: there are often well-placed observers who know almost immediately what went wrong. Sometimes those observers had even been warning that a disaster exactly like that was coming — that it was just a matter of time.

A few examples:

So what about the fatal collision two weeks ago? The initial evidence already fits this same pattern.

Shocking if not surprising investigations from the Wall Street Journal and ABC News find that pilots at Reagan National Airport, also known as DCA, had been formally warning the Federal Aviation Administration for more than three decades of nearly hitting military helicopters traversing the same corridor. Pilots who had faced this exact situation filed these reports to the FAA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System:

An investigation by the Washington Post is even more damning. Using simple, publicly available information, the Post’s reporters quickly discovered what the FAA had missed or ignored: The helicopter flight path and the airplane landing path at their closest point have a vertical separation of just 15 feet. And that separation assumes that aircraft, which must be under manual control in this area, fly perfectly. In reality, the Post’s analysis of actual flight paths from just one recent day found that several landing planes had entered the official helicopter flight path. And there is some reporting that it was not unheard of for helicopters to veer above the 200-foot altitude limit, upping the odds of entering the flight path for landing airplanes — a situation that appears to have happened just one day before the collision, when a Republic Airways flight aborted its landing at DCA to avoid a military helicopter flying below it at 300 feet.

All this raises an obvious question: If all this knowledge was so easy for outsiders to obtain, why didn’t leaders on the inside do this analysis in advance? If there are repeated warnings that a very specific type of disaster is “waiting to happen,” and the source of the problem is already known too, why wait for the tragedy and the “I told you so” before taking action?

There are actually several good, or at least organizationally understandable, reasons why that kind of proactive approach is easier said than done. Consider:

Hindsight is 20/20: Rarely did these observers know with certainty that the disaster they imagined would occur, much less how soon. An air safety system that can reasonably expect a fatal loss of a major airliner once every 50 years would be the safest in history; one that expects the same lapse every 5 years would, by today’s standards, rightly be considered a failure. But the difference is a matter of degree.

Disastership bias: The opposite of survivorship bias is at play: We mostly hear about these “it was only a matter of time” predictions when they come true. But many more never do — or indeed are patched in time. The public largely doesn’t hear about these.

The financial cost: Without knowing which of the predictions will come true and which won’t, safety authorities rightly have to pick and choose which ones to direct their finite resources to address, and which to leave be. It’s a pragmatic reality that many warnings can’t get fully acted on, and that some of those will eventually be proved right.

The political cost: Some disaster prophesies are so significant that they may implicate an entire program, paradigm, or organization. The Boeing Max crashes were like this: they cast doubt on whether the entire design philosophy used for the new airframe might have been mistaken. But the company’s entire strategic outlook, its theory of dominance against Airbus, was staked on that choice. The revelation that the choice was a mistake has now snowballed into a crisis of confidence in Boeing’s entire management paradigm of the past 30 years, one so profound that it now threatens the company’s very existence. The Columbia disaster was also like this, in that it revealed fatal flaws in the very concept of the shuttle — like the design decision to place the critical and fragile heat shield right next to the volatile launch system, and the failed promise of space flight that was so routine it was cheap.

The last of these costs is the most significant. No matter how much technical expertise and neutral proceduralism you throw at the problem, it simply runs against any large bureaucracy’s operational tides to surface concerns that could implicate its very legitimacy, its nature, its mandate to exist.

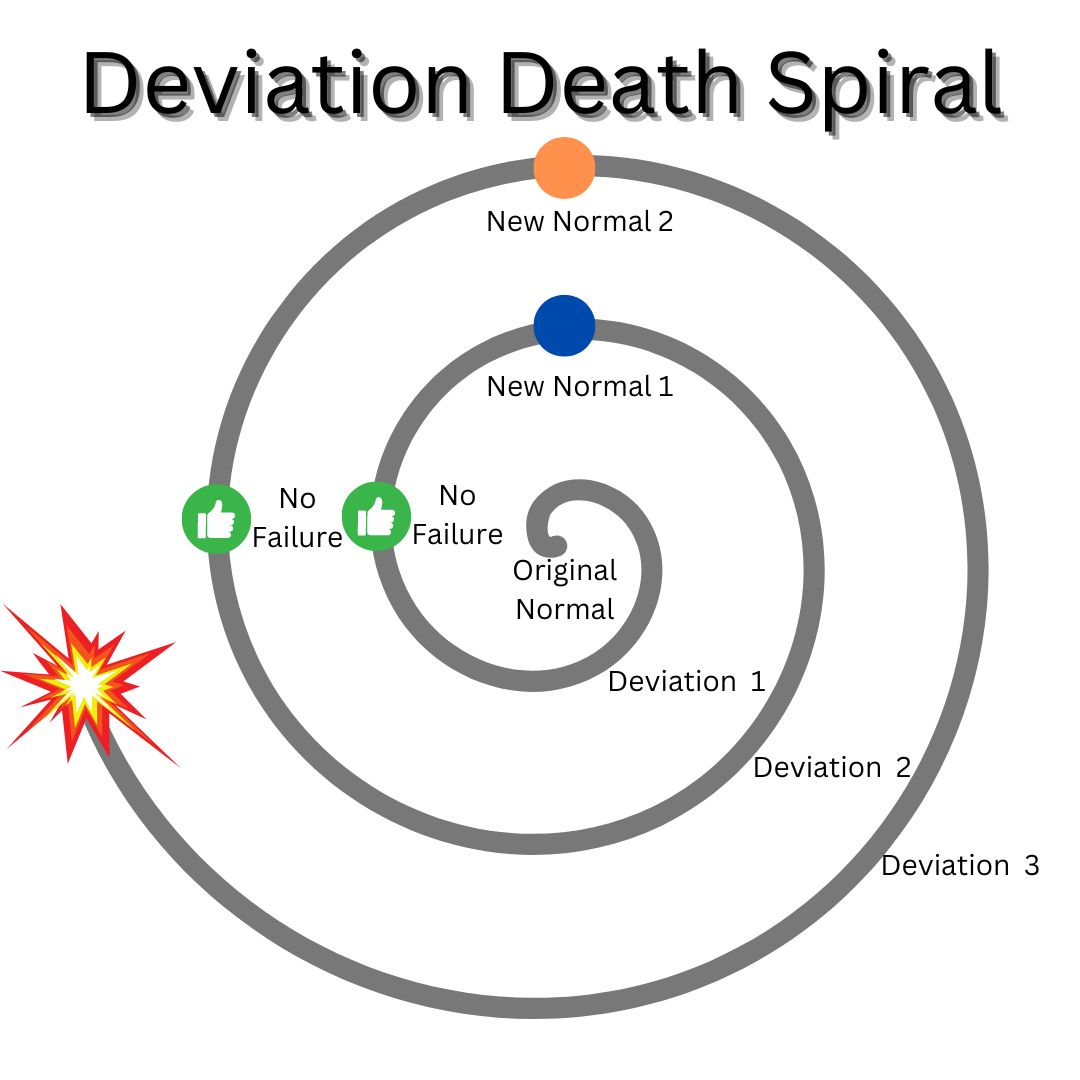

In safety studies, normalized deviance is the pattern by which a system creeps from labeling specific behaviors “dangerous” to labeling them “abnormal but not yet a proven danger” to labeling them “well, I know, but we’ve been doing it this way all along” to labeling them “normal”:

What is so curious about last week’s crash is that we had just had a 15-year period where no major U.S. airline suffered a fatal crash. It would have been hard for even the most optimistic observer in the 1960s or 1970s to have ever anticipated such a wild success — and the fact of it alone suggests that America’s air safety system remains one of the best examples in the world of addressing patterns like normalized deviance.

This in turn means that we should be wary of seeing the DCA crash as some freak exception. If a system has become one of the shining examples in history of solving a specific problem, only then to be embarrassed by precisely that problem, we shouldn’t be content just to say “even the best sometimes fail.” It may instead be that we failed to understand what the system really does, what it is and isn’t for.

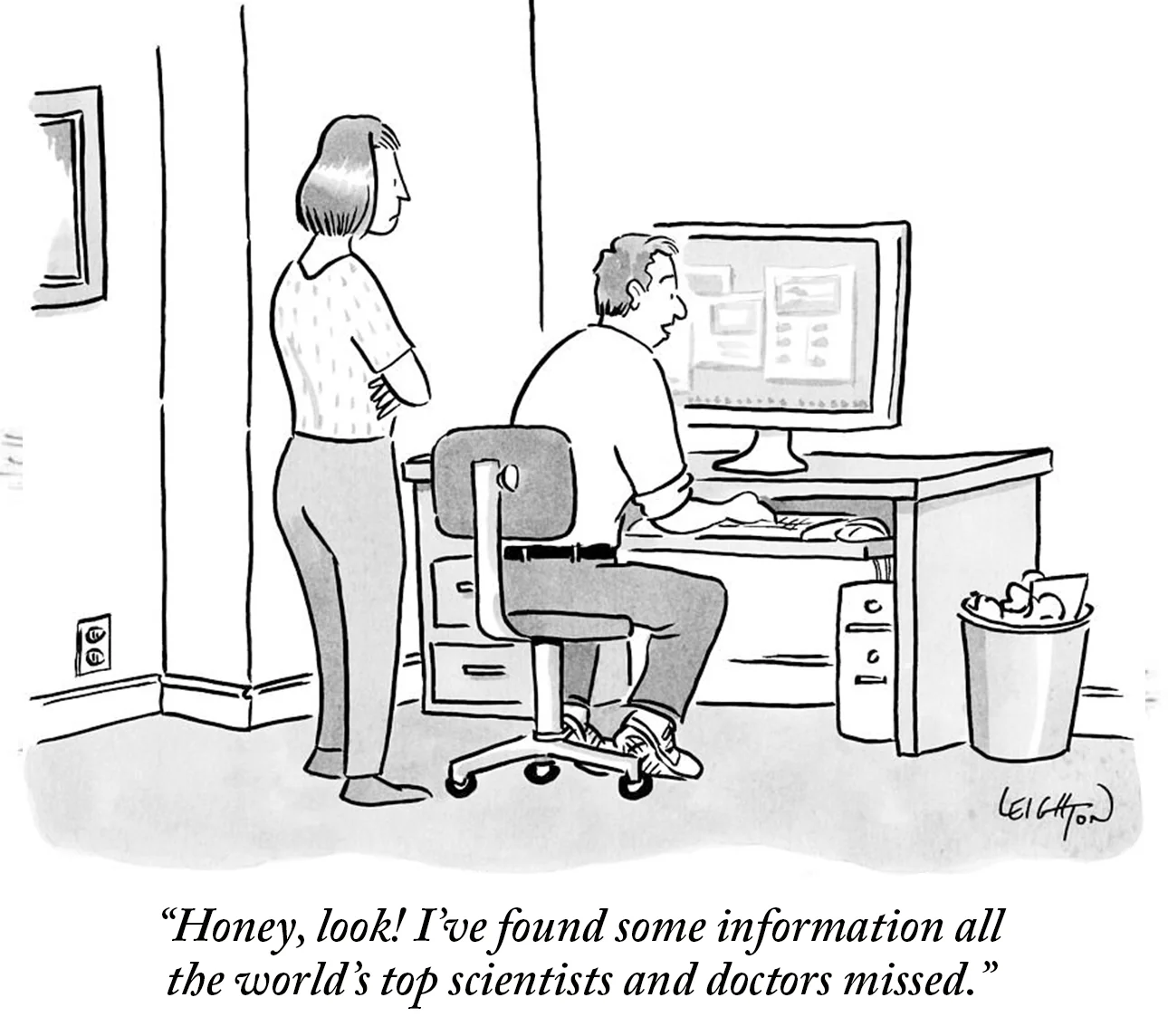

There’s an infamous comic making fun of the guy online who thinks he is proving all the experts wrong:

The comic is usually correct. But there really are cases where it is wrong. The January 29 crash looks like one of those cases. If you scroll through comments about the crash on news articles or YouTube, you will see obvious things stated that were somehow missed by the decisionmakers of the air safety system for the past third of a century. Let’s list a few of them.

It is insane — absolutely insane — to have an official helicopter flight path cross over a final descent path of one of the busiest airports in the country.

It is insane to do this while having the helicopters and landing planes use radio systems that don’t let them talk to each other.

It is insane to have the helicopters often be military craft on training missions, running with barely any lights, in the middle of a sprawling urban lightscape, at night.

It is insane to have those pilots often use night-vision goggles that block out their peripheral vision when the planes they have to watch for are arriving from the side.

It is insane to have the air traffic control tower managing this setup be understaffed, at just 63 percent of its FAA-recommended level as of September 2023.

It is insane for all this to happen below 1,000 feet, where the standard collision avoidance system for commercial aircraft by design shuts off.

In bare geometric terms, only two things stood in the way of all that insanity and a collision:

With over two million takeoffs and landings from Reagan Airport every decade, there are simply no human pilots and air traffic controllers who could have avoided these minuscule margins for error every single time.

If this sounds like undue speculation at this stage of an ongoing investigation, note that the FAA closed the helicopter flight path to all but emergency and presidential uses just two days after the collision. That is faster even than it grounded the Boeing Max fleet after two separate crashes made it obvious that the new plane’s design was faulty.

That is one of the odd consequences of the organizational patterns I’m describing: It really is the case that an insider who isn’t beholden to protecting the system, a sharp outsider, or even just a man on the street can sometimes easily see a devastating flaw that the organization itself doesn’t. This is such a common pattern that we cannot ascribe it to ordinary error, a process flaw, or even gross incompetence. And that is especially true at an organization with such a remarkable track record as the FAA.

This pattern arises because most organizations want to keep on existing, and want to ignore signs that they should not. The same is true for bedrock assumptions about what the organization is, what it’s for, or whether it is the right one to take on the problem it’s been tasked with. Paper clip factory managers are probably better than the average person at knowing how to make paper clips, but worse at knowing when you’d be better off using a stapler or just sending an email. The drive not to ask these existential questions permeates an organization’s design at every level, right down to what its smartest members see and what they’re blind to.

There are already signs that the DCA collision may meet this same pattern: that it didn’t just suffer a process lapse, like the deviation spiral illustration above, but showed the kind of perverse behavior that sets in when an organization is forced to manage a bad mandate it can’t change.

Consider the wide accommodations to typical air safety best-practices granted for military and government purposes. Not only was a major military base permitted to run helicopter training flights right by the airport, but it was doing so because those flights ferry diplomats, visiting officials, and other government VIPs around the city on a daily basis. These carveouts appear to have been as much imposed on the air safety system as granted by it. The FAA has a laser-focused safety mission, so far as it goes — but its authority has limits.

Or consider the enormous volume of flights permitted at DCA, which is such a sensitive airspace that any time new regular flights are added they must be specifically approved by Congress. They have been steadily growing for years in part due to members of Congress working to add direct access between the city and their home districts. And for good reason: Dulles Airport, conceived in 1950 to serve as the main airport for the capital, is so far away, so huge, and so over-designed that it might as well be a labyrinth on Mars.

Or consider the very decision to locate a major military base with a significant training mandate, the central buildings of all three branches of government, the headquarters of the military of the dominant world superpower, a helicopter flight path for ferrying an open-ended number of VIPs around the city at the discretion of a broad array of inside-the-Beltway government agencies, and the busiest runway in the United States all within a five-mile radius.

When an organization gets stuck in the rut of normalized deviance, extraordinary things must happen to shock it back out. It can be bold, charismatic new leadership. More often it is a dramatic, public catastrophe. These disasters can at times have a silver lining: an effective organization may newly find the will to patch not only the specific holes that allowed the disaster, but other holes it had been ignoring too. It can emerge even stronger than it was.

Two questions then should confront the country as we reckon with the Reagan Airport crash and work to prevent the next “just a matter of time” air disaster.

First: What can our air safety system do differently to patch these holes proactively? The answer must go beyond the oh-no-what-were-we-thinking window of opportunity for change that only briefly follows a disaster. It must mean understanding why air safety leaders ignored so many pilots warning of exactly this disaster — and figuring out how to change the incentives to make leaders actually seek those pilots out.

And second: Does the air safety system bear the ultimate blame here? Or did the military, hurried members of Congress, government officials eager to please VIPs, the perplexing design ideas of the Dulles planners, and the public itself place so many competing demands on the airspace around the Potomac that disaster truly was just a matter of time? If the answer is yes, then the air safety system might just be an easy scapegoat for a broader rot, and we could be setting ourselves up for this to happen again.

Keep reading our Spring 2025 issue

How gain-of-function lost • Will AI be alive? • How water works • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?