To my office till past 12, and then home to supper and to bed, being now mighty well, and truly I cannot but impute it to my fresh hare’s foote. Before I went to bed I sat up till two o’clock in my chamber reading of Mr. Hooke’s Microscopicall Observations, the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life.

Nature has all sorts of phenomena in stock and can suit many different tastes.

Imagine you are a castaway in a strange land — shipwrecked, plane-wrecked, spaceship-wrecked, or what have you. It’s now been a few months since the crash, and in that time you’ve begun to adjust to your new surroundings, building a shelter, finding food, and meeting your basic needs, but nothing to satisfy the gnawing hunger for rescue and home. One day, you notice something different on your morning walk. You squint, leave the path, and — behold! — small green shoots of what appears to be some kind of grain breaking a previously barren patch of earth. How do you respond?

A. You are not surprised. After all, you are a world-class botanist. You see your survival situation as less of a crisis and more of a puzzle for your high-functioning brain to solve, as you tell yourself, “I’m gonna have to science the s*** out of this.” Literally. Because not only have you tilled the soil in neat, orderly rows, sowed seeds, built your own irrigation system, and precisely calculated the yield of current and future crops, but you have also fertilized the soil with your own excrement. You are not from the deplorable herd of Yahoos in Gulliver’s Travels, wallowing in your own filth and ignorance. No, even your basest animal instinct glorifies your human ingenuity. You are the master, the monarch of all that lies before you, and you pursue your destiny with the scepter of Knowledge in your hand and your handmaiden Science at your side.

B. You are astonished — so filled with wonder, in fact, that you conclude it could be nothing less than a miracle. How else could grain that you didn’t plant and that doesn’t appear to be native to this land grow except by the Hand of Heaven intervening in Creation for your benefit? God hath taken pity on this poor miserable sinner and spread “a table in the wilderness,” as He did for the Israelites. You tend to your crop, and your thankful heart sings that your exile is actually your deliverance.

C. You are surprised but do not marvel long. Yes, you did have a pack of seeds with you and it’s possible you dropped some on the ground. Yes, it’s quite unlikely that the conditions — the season, amount of sunlight and water, soil quality — would align perfectly for the seeds to sprout. But as much as you’d like to attribute meaning to this event, you know the world is contingent and life arises randomly. Plus, even if the universe were on your side, why would it take interest in you, tiny speck that you are? Chance just happened to be in your favor this time, you lucky dog.

D. All of the above.

If you answered A, you might be Mark Watney, the fictional astrobotanist stranded on Mars, played by Matt Damon in the 2015 film The Martian. Clearly, you are a paragon of Enlightenment optimism and Steven Pinker’s hero. If you chose B, you occupy a distinctly pre-modern, some might even say “medieval,” headspace. You show Luddite tendencies and probably have a penchant for tweed suits. If you selected C, you probably turn to evolutionary psychology, Carl Sagan, or Stephen Crane to reassure yourself when you can’t help but feel there might be something unique about the human experience.

But if you find yourself alternately optimistic about what you can achieve and disappointed in your limits and failures, if you want to believe there is something more to the universe than atoms colliding but find faith in a higher power or a transcendent reality difficult to sustain in the modern world, then you probably selected D. You are Robinson Crusoe.

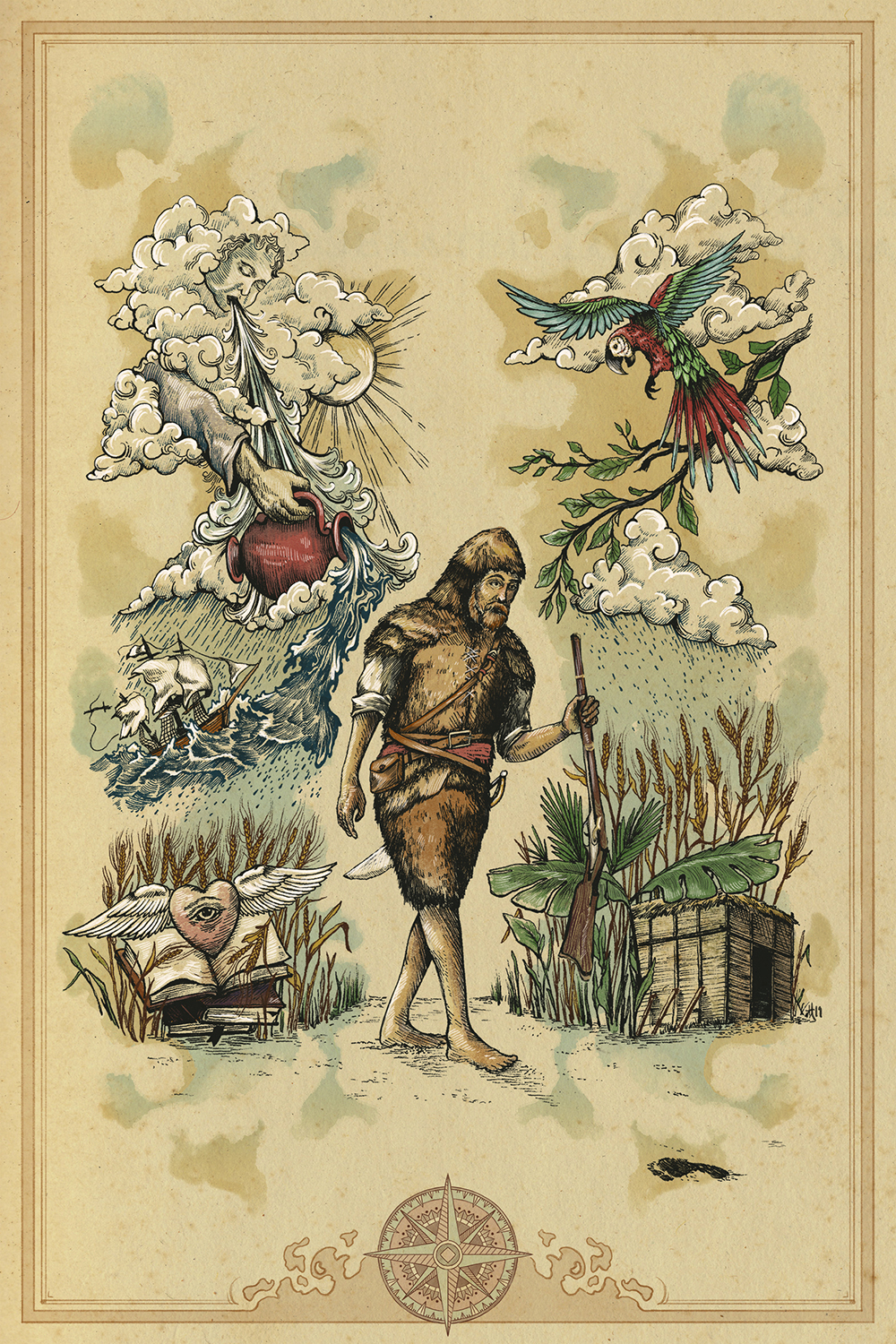

When Daniel Defoe published Robinson Crusoe three hundred years ago in 1719, it was an instant bestseller, and since that time it has not given up its hold on our imagination. The story of a man and his companion Friday, cast away on a Caribbean island, is as familiar to us as any fairy tale, even if we haven’t read the book. Like its footprint in the sand, Robinson Crusoe has left a sign on the cultural landscape, even giving its name to an entire genre known as the “Robinsonade” that includes novels like Treasure Island, The Swiss Family Robinson, and Lord of the Flies, and TV shows and films like Gilligan’s Island, Cast Away, and Lost.

So what is it about Robinson Crusoe? Samuel Taylor Coleridge believed Defoe’s castaway was representative of “universal humanity.” Edgar Allan Poe wrote that the appeal of the novel lay in its power of our identification with its hero. Virginia Woolf wrote “there is no escaping him,” in the same way as there is no escaping the “cardinal points of perspective — God, man, Nature.” Others have explained the novel’s enduring popularity by pointing out how it sustains multiple interpretations. English professor Thomas Keymer writes that “the novel rewards analysis as many things — an exotic adventure story; a study of solitary consciousness; a parable of sin, atonement, and redemption; a myth of economic individualism; a displaced or encoded autobiography; an allegory of political defeat; a prophecy of imperial expansion — yet none of these explanations exhausts it.” Robinson Crusoe is a classic because it contains multitudes.

Early critics had also called this Rorschach-inkblot quality of the novel its “double character,” because the book appeared as multiple things at once, even embodying polarities. This double character is striking at every level of the novel. Is it, as some of its first readers wondered, fact or fiction? Is it the work of a genius or a hack? How did a novel manage to entertain everyone from children to the poor working classes to intellectual elites like Alexander Pope, Rousseau, Marx, and John Stuart Mill? As the essayist Thomas De Quincey put it in 1841, how does Defoe make his novels “so amusing, that girls read them for novels; and he gives them such an air of verisimilitude, that men read them for histories”? Every encounter with the novel seems as surprising and fresh as it seems familiar.

In Robinson Crusoe, we can witness the emergence in the literary canon of the Janus-faced consciousness that is our distinctly modern way of experiencing the world. It is a way in which it is possible to look at a remarkable event sometimes as a miracle and sometimes as a natural phenomenon, to read our horoscopes while trusting medical journals, to raise children who declare allegiance both to NASA and to Gryffindor House, to believe that love has a higher, even transcendent, purpose at the same time as we believe it was naturally selected for because it is a pro-social behavior that helped our species survive. Robinson Crusoe registers that modernity is not the condition of uncertainty about whether we are enchanted or disenchanted, superstitious or scientific; it is the condition of being both.

In his book A Secular Age (2007), Charles Taylor describes the “cross-pressures” of modernity, the way many of us experience the world as a tug of war between conflicting belief systems. Some of us “want to opt for the ordered, impersonal universe, whether in its scientistic-materialist form, or in a more spiritualized variant,” yet we “feel the imminent loss of a world of beauty, meaning, warmth, as well as of the perspective of a self-transformation beyond the everyday.” Think of Victorian humanists like George Eliot or Thomas Hardy, or anyone who grew up in a Christian family and now attends services only at Christmas, out of nostalgia or family tradition. Others opt for faith, yet remain “haunted by a sense that the universe might after all be as meaningless as the most reductive materialism describes. They feel that their vision has to struggle against this flat and empty world; they fear that their strong desire for God, or for eternity, might after all be the self-induced illusion that materialists claim it to be.”

Whatever we profess to believe, we all share an experience that is structured by scientific, materialistic concepts, encouraging us to sense that we occupy a natural, this-worldly realm, rather than a supernatural, transcendent one. Taylor calls this naturalistic realm the “immanent frame.” Imagine it as like living in a house. For those who live strictly in the immanent frame — think of Steven Pinker, Richard Dawkins, Carl Sagan, Sam Harris — the doors and windows are shut. This world is all we have; there is nothing more. Others are open to peering out the windows. Many more still are caught at the threshold and unsure whether to keep the door open or closed. These opposing pulls are the “cross-pressures” of modernity. For Taylor, this also describes most religious believers today: in the modern age, “the struggle for belief is never definitively won.”

Robinson Crusoe falls squarely in the middle of a long tradition of castaway stories in which the struggle for survival becomes a stand-in for the struggle for belief. But it may be the first to capture what it is like to feel “some of the force of each opposing position,” as Taylor describes the cross-pressures. As we will see, Defoe’s novel can be read in part as a response to the utopian vision of Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627), a story about a remote society that has brought empirical science and revealed religion into harmony. In turn, the hit TV series Lost can be read as our era’s mysterian, angst-ridden response to the epistemic problem raised by Defoe. Situated in this way, Robinson Crusoe can be seen as a crucial stage in the emergence of the modern double consciousness — the point when a union between the natural and the transcendent could no longer be taken for granted, but perpetual and global conflict did not yet seem inevitable.

Defoe’s novel shares with other castaway narratives — Homer’s Odyssey, Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island, and Lost, to name a few — the trope of the mysterious island. What makes Crusoe’s island mysterious is the doubleness of mind his experience of it invites. Again and again, phenomena on the island resist his best efforts at observation and interpretation.

During a terrible storm at sea, Robinson Crusoe is swept ashore on an island somewhere in the middle of the Caribbean, sole survivor of his shipwreck. In spite of his “Confusion of Thought” while in the water, Crusoe manages to narrate in excruciating detail every view he has of the shore, the cresting and breaking of every wave over his head.* When he lands, he describes life on the island with the precision of a lab report. As if repeating the numerical listings in Genesis of the dimensions of Noah’s Ark, Crusoe details the precise location, shape, and size of his new shelter: “It was on the N.N.W. Side of the Hill, so that I was shelter’d from the Heat every Day, till it came to a W. and by S. Sun, or thereabouts, which in those Countries is near the Setting,” and so on. Nothing on the island escapes his zeal for order, not even things that can’t be quantified. Crusoe, “like Debtor and Creditor,” catalogues into two columns each good and evil he’s experienced, with God’s blessings subject to the same logic and categorization as his ammunition supply.

Yet, in spite of Crusoe’s diligent observation, the island resists empirical certainty. The more he counts, the more we can’t help but think we’re looking at his island through a kaleidoscope. For example, Crusoe rescues two cats from the ship, then later finds three kittens of the same breed. But the wild cats on the island seem to be of a different breed, and Crusoe notes that, “both my Cats being Females, I thought it very strange.” At another point, despite keeping a calendar by faithfully cutting notches on a post every day, he somehow loses count of the days. In another strange episode, when he is hunting, a “great Fowl” he initially takes for a hawk turns out to be a parrot. Again and again, small happenings on the island undermine Crusoe’s efforts to perceive it “plainly,” as he often says. This is not a place to be precisely measured and counted but one that eludes accurate observation, a place where cats multiply without reason, days sometimes disappear, and parrots look like hawks.

It’s not only the mysterious features of the island but Crusoe’s shifting perception and attitude that transform the island into a house of mirrors. Throughout the novel, he describes the island alternately as a “little Kingdom” and a “Prison,” a civilized English “Country House” and a “Wilderness” and a “barren uninhabited Island.” Crusoe teases the reader with the strange ambiguity of the island with his famous reference to “the sixth Year of my Reign, or my Captivity, which you please.” Is the island a duck or a rabbit — or both?

Another unexplained feature of Crusoe’s time on the island is his apparent prophetic power — his imaginations and dreams sometimes become realities. In one memorable passage, Crusoe humorously fantasizes about being the king of the island surrounded by his loyal subjects: “I could hang, draw, give Liberty, and take it away, and no Rebels among all my Subjects. Then to see how like a King I din’d too all alone…. My Dog who was now grown very old and crazy … sat always at my Right Hand, and two Cats.” Later, when cannibals come to the island, Crusoe rescues two of their European captives who, along with Friday, become his faithful subjects, and he muses “How like a King I look’d.” Toward the end of the novel, when a crew of English sailors lands on his island, they call him its “Governour.” Similarly, he obsesses over how he could rescue the cannibals’ victims, dreaming that “on a sudden, the Savage that they were going to kill, jumpt away, and ran for his Life; and I thought in my Sleep, that he came running into my little thick Grove.” He later goes on to rescue Friday in a scene that unfolds almost exactly like his dream.

Yet another mysterious aspect of Crusoe himself is his astonishing industriousness. Over the course of the novel, he becomes a skilled potter, shipwright, hunter, farmer, tailor, architect, carpenter, baker, and basket weaver. His success on the island nearly puts to shame The Martian’s Mark Watney, who singlehandedly grows potatoes on the Red Planet. How does Crusoe accomplish it all? As he explains, with enough labor, time, and reason, “every Man may be in time Master of every mechanick Art. I had never handled a Tool in my Life, and yet in time by Labour, Application, and Contrivance, I found at last that I wanted nothing but I could have made it, especially if I had had Tools.” And later he says, “I seldom gave any Thing over without accomplishing it, when I once had it in my Head enough to begin it.”

It was this Enlightenment spirit of optimism about human capabilities that philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau admired most about the novel. In Emile, his treatise on education, the only book the protagonist is allowed to read before the age of twelve is Robinson Crusoe, because Rousseau believed children ought to be taught to rely on themselves, to imitate Crusoe’s stolid industriousness. And yet, Crusoe’s feats make him look more like Hercules undergoing his Labors than a middle-class English merchant’s son fighting to survive on an island. Even his more mundane doings have a shimmer of the unreal.

Crusoe’s island is mysterious because he often cannot explain why things happen there and what causes them. This stands in contrast to his methods of investigation, his desire to know causes “plainly” — methods that closely align him with the new inductive philosophy of the Enlightenment, particularly that of Francis Bacon, John Locke, and the Royal Society in the seventeenth century. Plainness — in thinking, knowing, and writing — was a defining virtue of their project, based on newfound confidence in the power of observation.

In the empirical philosophy of Bacon and Locke, the senses, especially vision, were a reliable guide for interpreting and understanding the natural world. Humans naturally had the capacity for reason, and all that was needed for scientific progress was the application of the senses and reason to the natural world. For the empiricists, contrary to the method of doubt of many Enlightenment thinkers inspired in part by Descartes, we could trust our senses to give us true knowledge about the world, at least if we carefully followed the right process for organizing our sensory perceptions. As with Crusoe’s insistence that, given enough labor and time, he can accomplish anything, so too with the optimism of the empiricists: As long as you followed scientific methods of inquiry, it was possible to trust that the world is as it seems to be, and there would be no immovable barriers to explaining why things happened and what had caused them to happen. According to Locke, once these new explanations were discovered, they were to be communicated in the simplest, plainest prose style possible, eschewing elaborate, overly figurative, stylistic flourishes that serve only to obscure rather than clarify the truth. Plain truth calls for plain writing.

Crusoe often uses the word “plain” when he sees or discovers something: “I plainly saw,” “very plain to be seen,” “they might be plainly view’d,” “by my Observation it appear’d plainly,” “my Eye plainly discover’d.” Indeed, assigning straightforward, or “plain,” causes to phenomena on the island motivates Crusoe’s constant efforts to observe, measure, and record. Soon after he’s marooned, he looks out to sea and believes he sees a ship on the horizon. He strains his eyes so much he becomes “almost blind” and then, in frustration at how he’s increased his “Misery by [his] Folly,” he “weep[s] like a Child.” Later, Crusoe turns to scientific instruments, again staking his prospects for salvation on his observational abilities: “I resolv’d to go no more out without a Prospective Glass in my Pocket.”

The book as a whole also largely follows the empiricists’ stylistic mandate: Readers have often remarked on the novel’s plainness, or, according to Virginia Woolf, its “magnificent downright simplicity.” Yet in many places, plainness falters: When Crusoe spreads his poetic wings and soars into metaphor, readers are left with incommensurable views of the island — as simultaneously a prison and a castle, a spiritual punishment and a blessing.

But Crusoe resorts to figurative speech for a reason. Just about everything that perplexes him either has an unknown cause or poses a difficulty in connecting cause and effect. On Crusoe’s island, plain observation does not narrow possible interpretations but proliferates them, counting and numbering exposes even more casualties than were visible at first glance, and with increased scientific investigation the island only becomes more mysterious.

The double character of Crusoe’s mental world comes to the fore in one of the most famous scenes of the novel, where Crusoe is “surpriz’d and perfectly astonish’d” to find ears of English barley growing. His first guess is divine intervention “directed purely for my Sustenance, on that wild miserable Place.” He has good reason for his hypothesis — the barley, so perfectly suited for providing him nourishment, is not native to the island — and seeks confirmation by investigating for more, “peering in every Corner, and under every Rock.” Only later does he recall how he “had shook a Bag of Chickens Meat out in that Place … and I must confess, my religious Thankfulness to God’s Providence began to abate.” Despite his disappointment, he sows the seeds, increases the yield, and eventually makes bread, all in typical Crusoe fashion.

But later he proclaims “Thanks for that daily Bread” and urges himself “to consider I had been fed even by Miracle, even as great as that of feeding Elijah by Ravens.” As to the island itself, Crusoe reflects that he “could hardly have nam’d a Place in the unhabitable Part of the World where I could have been cast more to my Advantage,” having “no ravenous Beast, no furious Wolves or Tygers to threaten my Life, no venomous Creatures or poisonous, which I might feed on to my Hurt, no Savages to murther and devour me.”

The passage strikingly resembles a popular idea during the Enlightenment, in which natural theologians argued for the existence of God from the proof of His benevolent design in creation. Richard Blackmore, a poet and esteemed physician who studied nervous disorders and smallpox, wrote in his anti-materialist epic poem Creation (1712):

See how the Earth has gain’d that very Place,

Which of all others in the boundless Space

Is most Convenient, and will best conduce

To the wise Ends requir’d for Nature’s Use.

What Crusoe says also mirrors contemporary Enlightenment debates about the existence of miracles. Contrary to what we might expect, many natural philosophers in the Royal Society, including John Locke and Robert Boyle, believed miracles existed and that the natural sciences could both refine their understanding of what miracles were and provide better evidence that they actually happened, thereby also strengthening the rational arguments for the truth of Christianity. As literary scholar Jane Elizabeth Lewis explains in Religion in Enlightenment England (2017), the questions that had become urgent were “how to know that the agent is divine? Or that, indeed, a work beyond the ordinary power of nature has been produced in the first place?” What the Enlightenment was newly committed to was not disproving miracles, but using science to defend them, demonstrate that they had happened, give new rigor to understanding them, and more accurately distinguish them from natural events. For example, Samuel Clarke, a prominent philosopher, defended miracles in light of Newtonian physics, proposing a new metric for distinguishing natural cause from miraculous intervention.

Here, too, Defoe engages a broader theological and scientific debate of his time, while destabilizing the prevailing optimism that the new science will clear the path to enlightened thinking. When he mentions miracles, it is usually couched in uncertainty: “next to miraculous,” “by a kind of Miracle,” “as if it had been miraculous,” “it had something miraculous in it.” As for the barley episode, Crusoe is never certain about whether it was miraculous or the result of chance, and later in the novel, he speaks as if it may have been both — he probably dropped the seeds, but still he had been “fed by Miracles.” Crusoe’s reconciliation between the duck and the rabbit images he sees is tenuous, and epistemic crisis lurks just out of sight.

Enlightenment thinkers were also committed to settling, once and for all, the question of demons, angels, apparitions, and the rest of the spirit world. In another famous episode, Robinson Crusoe is again “exceedingly surpriz’d” when one day as he’s walking toward his boat he sees

the Print of a Man’s naked Foot on the Shore, which was very plain to be seen in the Sand: I stood like one Thunder-struck, or as if I had seen an Apparition; I listen’d, I look’d round me, I could hear nothing, nor see any Thing, I went up to a rising Ground to look farther, I went up the Shore and down the Shore, but it was all one, I could see no other Impression but that one, I went to it again to see if there were any more, and to observe if it might not be my Fancy; but there was no Room for that, for there was exactly the very Print of a Foot, Toes, Heel, and every Part of a Foot; how it came thither, I knew not, nor could in the least imagine.

We see here again the language of plain observation, followed by the methodical search for a cause, for which the senses fail. Crusoe then again becomes split between reasons in support of supernatural and natural causes. Because he can think of no natural explanation for the footprint, “I fancy’d it must be the Devil; and Reason joyn’d in with me upon this Supposition.” But then he entertains counterarguments, and considers a new hypothesis “that it must be some more dangerous Creature,” perhaps “some of the Savages of the main Land.”

Was it possible to use science to investigate the spirit world? As with miracles in the barley episode, Crusoe’s use of observation and reasoning reflects a newfound optimism that scientific methods could be used to banish ignorance and to give us new, certain knowledge about the supernatural. Indeed, Defoe himself published several works about the occult, including Serious Reflection During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: With His Vision of the Angelick World (1720), a sequel novel, and the treatises A System of Magick (1726), The Political History of the Devil (1726), and An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727). In these works, Defoe adopts scientific language to test knowledge of the spirit world. As to “the Possibility however of Apparitions, and the Certainty of a World of Spirits,” he writes in the History and Reality of Apparitions, “I think the Evidence will amount to a Demonstration of the Facts, and Demonstration puts an end to Argument.” For Defoe and his contemporaries, then, it was not strange to talk about studying spirits with the same language we use to talk about conducting chemical research in a lab.

But the religious optimism we found in the barley episode, and at first seem to find again in the footprint scene, is soon muddled. For Crusoe then begins “to perswade my self it was all a Delusion; that it was nothing else but my own Foot.” What is at stake here is not only, as with miracles, correctly distinguishing supernatural from natural causes, but something more freighted — the worry “that all this might be a meer Chimera of my own.” Crusoe not only wonders if he might have been wrong, but considers whether “I had play’d the Part of those Fools, who strive to make stories of Spectres, and Apparitions; and then are frighted at them more than any body.” After making further observations of the footprint, again intensively weighing the possibilities of natural and divine causation, Crusoe decides against the delusion hypothesis, arriving at the real conclusion: that “savages” occasionally visit the island. (Contrary to popular belief, this is not Friday’s footprint he spots on the sand.)

What is happening here to cause Crusoe’s earlier scientific optimism to give way to self-doubt, at least momentarily? Like other Enlightenment thinkers, Defoe was interested in distancing himself from ignorance and superstition about the spirit world, both in the legacy of medieval Roman Catholicism and in pagan religions — both of which, on Defoe’s account, were unenlightened because they kept the distinction between natural and supernatural causes shrouded in mystery. He aligns pagan and Papist religions explicitly when Crusoe, teaching Friday about Christianity, criticizes that “the Policy of making a secret of Religion, in order to preserve the Veneration of the People to the Clergy, is not only to be found in the Roman, but, perhaps among all Religions in the World, even among the most brutish and barbarous Savages.” Unlike this obscuring of causes, making religion and its logic a secret, Crusoe methodically, empirically tests his own supernatural theories.

In contrast to Crusoe’s brief uncertainty about whether he’s being deluded, Defoe exploits for comedic effect the opposite dynamic — Crusoe knowing he isn’t deluded while someone else is. When Crusoe and Friday, guns blazing, rescue Spanish sailors from cannibals, the pagans see “Heavenly Spirits, or Furies, come down to destroy them … for it was impossible to them to conceive that a Man could dart Fire, and speak Thunder, and kill at a Distance without lifting up the Hand.” But the Catholic sailors are hardly more enlightened, as one amazed man, when Crusoe rescues him, asks tremblingly, “Am I talking to God, or man! Is it a real Man, or an Angel!” This serious, emotionally fraught moment collapses into bathos when Crusoe responds, “Be in no fear about that, sir, said I, if God had sent an Angel to relieve you, he would have come better Cloath’d, and Arm’d after another manner than you see me in.”

In this comic moment, the reader sees what Crusoe cannot: Though Crusoe laughs at the Spanish sailor and the pagan cannibals as demon-haunted fools, his own beliefs about demons and spirits are not that dissimilar from theirs. The satire here lays the groundwork for the Sagan–Pinker option we saw at the beginning: What if the new scientific approach eventually leads us to wonder whether not just some but all supernatural beliefs are delusional?

If Defoe could deflate the hopes for a scientific union between the natural and the supernatural, it was only because Francis Bacon taught us to dream it was possible. Bacon, often called the “father of empiricism,” wrote his own castaway story — and we can see the problems Robinson Crusoe raises for Bacon’s empiricism by reading the novel as a play on the utopian fantasy of New Atlantis.

Bacon’s New Atlantis [from which this journal takes its name –Ed.] was published as an unfinished “fable” in 1627. It is narrated by an unnamed sailor aboard a ship, who together with his crew were lost and encountered an unknown island somewhere off the coast of Peru. The island, Bensalem, is already home to a morally perfect and scientifically advanced Christian civilization. After the crew is granted safe haven, they learn about the country’s most esteemed institution, Salomon’s House, which is dedicated to the interpretation of nature. “The End of our Foundation,” says the Head of the House of Salomon, “is the knowledge of Causes, and secret motions of things.”

The generic difference between Robinson Crusoe and New Atlantis is a telling one: New Atlantis is a utopia, envisioning an ideal society that is able to use science to explain the natural world and its causes, to know creation, while Robinson Crusoe, far more skeptical of that possibility, is a realist novel. It is significant also that Bensalem is already home to a utopian society, while Crusoe’s island is uninhabited, and Bacon’s narrator survives with an entire crew, while Defoe’s hero is alone on the island, as if to illustrate the modern educational ideal that each of us learns to think for ourselves. In Bacon’s fable, the confidence in empirical inquiry empowers a whole society to become a “mirror in the world,” and a model for all other societies; in Defoe’s novel, as the ordering principle of a solitary consciousness, it threatens epistemic crisis.

Take, for instance, the confidence of Salomon’s House in our ability to know the world by observing it plainly, which is precisely what Crusoe struggles to achieve throughout the novel. Salomon’s House, as one member says in a prayer, seeks “to know thy works of creation, and the secrets of them” — which may seem again to align the Baconian ideal with Crusoe, who skewers Catholics and pagans for their obscuring of causes, making religion and its logic a secret. Yet when others mistake Crusoe for a divine figure, we can’t help but question his own conclusions about the spirit world, even if his uncertainty is portrayed as more enlightened. The spoof of the Catholic sailor silently carries with it the worry that Crusoe might be revealed as similarly foolish. Defoe, perhaps in spite of himself, reveals the Baconian optimism that science can stably incorporate the supernatural to be an anxious balancing act.

The doubt over whether Crusoe has achieved the ideal of Salomon’s House or is actually more like the superstitious Catholics and pagans is heightened by an ambiguous dream vision he has early in the novel, which echoes a religious vision in Bacon’s story. In New Atlantis, the Governor of Bensalem, asked by the stranded crew how Christianity came to the hidden island, recounts the story: Twenty years after Christ’s Ascension into Heaven, “a great pillar of light” appeared in the water near their island, “rising from the sea a great way up towards heaven: and on the top of it was seen a large cross of light.” One of the wise men from the Society of Salomon’s House prayed, asking God “to give us the interpretation” of the vision, “which thou dost in some part secretly promise by sending it unto us.” The wise man’s prayer was answered, and as he approached the cross of light it broke apart, leaving a cedar chest. Swimming out to retrieve it, he found inside the Old and New Testament and a letter from the Apostle Bartholomew, testifying the truth of the Gospels.

In Bacon’s utopia, visions are undoubtedly the work of God, and, what is more, it is made clear that the new covenant is made between God and men of science. The wise man’s prayer, thanking God for granting man the ability “to discern … between divine miracles, works of nature, works of art, and impostures and illusions of all sorts,” becomes the mandate of Salomon’s House. Science is now, with God’s direct sanction, in the service of Christian faith — understanding God’s creation and having the ability to distinguish clearly between the workings of Providence and nature.

Crusoe’s own heavenly vision has striking parallels. One night, delirious from fever, hunger, and thirst, Crusoe prays himself to sleep, asking God for pity. In a dream, he is visited with a “terrible Vision.” A man whose “Countenance was most inexpressibly dreadful” descends “from a great black Cloud.” “He was all over as bright as a Flame … and all the Air look’d, to my Apprehension, as if it had been fill’d with Flashes of Fire.” Crusoe hears a voice say, “Seeing all these Things have not brought thee to Repentance, now thou shalt die,” and the man lifts a spear as if to kill him.

But unlike the vision in New Atlantis, Crusoe’s is much less obviously a divine intervention. Even were it presented as a waking vision, it would violate the increasingly strict Enlightenment standards of proof that miraculous events needed to be authenticated by multiple witnesses, examinations, and testimonials. The vision in New Atlantis meets this criterion, but Crusoe’s vision does not. A delirious fever dream rather than a waking vision, it cannot be proved that it was in fact a supernatural interruption of the natural order. Defoe again seems to be inviting against Crusoe the same sorts of doubts he raises against the demon-haunted Catholics and pagans.

Though God is much more obviously at work in the world of New Atlantis than in the world of Crusoe, Crusoe’s vision and, before this, the “next to miraculous” growth of the barley, nevertheless catalyze his conversion to Christianity. Following the dream, Crusoe gradually recovers from his illness and in reflecting upon his vision constructs a series of syllogisms about the nature of the universe, God’s will, and his own fate. He reasons that if God “guides and governs” the natural world, then nothing can happen without His “Knowledge or Appointment.” And if nothing can happen without God’s knowledge, then God must know that he, Crusoe, is on the island. To this conclusion, Crusoe asks, “Why has God done this to me? What have I done to be thus us’d?” No beam of light bursts from the clouds, no voice calls down to Crusoe from heaven. Instead, “like a Voice,” his “Conscience” speaks to him, exhorting him to repent for his “mis-spent Life.” At this point, Crusoe himself is “struck dumb” and, as in the conversion of Bensalem, he opens a “Chest” and finds “a Cure, both for Soul and Body.” The cure in the chest is again a copy of divine Scripture, although not miraculously descended from above, and without a letter from Bartholomew — along with some tobacco, which Crusoe proceeds to soak in rum.

It is in his rum-soaked, tobacco-smoked state of mind that Crusoe attempts to read from the Bible. He continues this physical and spiritual cure for several days, beginning to read “seriously” from Scripture, methodically meditating on his past life, until he “threw down the Book, and with my Heart as well as my Hands lifted up to Heaven, in a Kind of Extasy of Joy, I cry’d out aloud, Jesus … give me Repentance!” This moment was the first, Crusoe says, that “I could say, in the true Sense of the Words, that I pray’d in all my Life.”

Though Crusoe marks this conversion as a turning point between his past life as a sinner and his new life as a repentant believer, a turn that gives him a “different Sense” and new “Notion” of his life on the island, his thoughts of doubt and uncertainty remain relatively unchanged for the rest of the novel. Not only is Crusoe’s conversion less credible to the reader than the conversion of Bensalem — fueled as it is by illness, rum, and tobacco — but it doesn’t give him new knowledge in the same way: Crusoe continues to be mystified in his attempts to discern the will of Providence, while the inhabitants of Bensalem are given clear instructions to found a scientific society that will be in the service of Christian faith.

Despite the Enlightenment’s optimism that science could provide a higher standard of proof for the existence of miracles, Defoe offers us a world in which conversions are no longer grounded in clear proof that the supernatural has broken in on the natural world — no mass waking vision witnessed by an entire island, no texts dispatched from the heavens and retrieved from the sea. Instead, we have an epiphany that, however powerful, cannot long keep doubt at bay. Here, unlike in New Atlantis, Charles Taylor’s words hold true: “the struggle for belief is never definitively won.”

The clearest descendent today of the Enlightenment castaway narrative, and the proof that the modern age has inherited the legacy of Crusoe rather than Bacon, is the TV series Lost. Whereas New Atlantis is a fable that allegorizes the perfection of human knowledge through science, Lost is an allegory of the opposite: the ways modern life can thwart not only our attempts of arriving at knowledge with certainty but also our ability to find existential meaning.

Lost, which aired on ABC from 2004 to 2010, tells the story of the survivors of Oceanic flight 815 when it crashes on a mysterious island in the Pacific. The names of the characters signal the show’s interest in Enlightenment-era thinkers: Locke, Hume, Rousseau, and Burke, to name a few. Danielle Rousseau lives out her namesake’s theory about the individual living in a state of nature. And in a deep cut, John Locke’s father is named Anthony Cooper, after the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, the real philosopher’s patron.

Even if the correlations between characters and their namesakes are usually tenuous, the choice signals the show’s allegorical method and its interest in the larger philosophical problems we have inherited from the Enlightenment. One of the appeals of castaway stories, as Virginia Woolf pointed out about Robinson Crusoe, is that they miniaturize the drama of the relationship between man, God, and Nature — the “cardinal points of perspective.” Lost is no different. The show is not just an entertaining adventure story about individuals fighting for survival on an island, but is also a microcosm for how competing belief systems try to make sense of the strange world we find ourselves in. None of these philosophies, the show suggests, fully alleviates our sense of being lost; none wholly explains life’s mysteries.

Even before they crashed on the island, a number of the characters were already outcasts. Kate is a fugitive, Sawyer is a con artist grappling with the trauma of his childhood, Mr. Eko is a Nigerian drug lord turned priest, Hurley spent time in and out of a psychiatric facility before being singled out by winning the lottery, and Sayid tortured enemies for Iraq’s Republican Guard. Even those who occupy more conventional social positions — Locke, Jack, Desmond, Michael — share a sense of restlessness and unease, of being uncomfortable and out of place in the world.

Many of the characters explore different sources of meaning and self, and are ambivalent about living in a transcendent frame. The most obvious examples are John Locke and Mr. Eko, both of whom experience spiritual conversions on the island but continue to suffer doubt. Claire is baffled that Charlie might find spiritual comfort in a statue of the Virgin Mary, though she visits a fortune teller before the crash. In a flashback, we see Charlie halfheartedly confessing his sins in a confessional. Hurley is certain he sees ghosts, but his doctors insist that they are hallucinations, a chemical imbalance to be cured by his medications. Desmond, in his quixotic search for meaning, spends a brief time in a monastery.

The island, kaleidoscopic like in Robinson Crusoe, does nothing to help them choose. Whispers in the jungle, mysterious hatches, wild coincidences, apparitions, a strange black cloud with the power to kill, and the presence of a polar bear elude straightforward explanations. The character who is most attuned to the mystery of the island and most determined to find answers is John Locke. Before the crash, Locke was a solitary, low-level office worker, confined to a wheelchair after he broke his back in an accident. When the plane crashed on the island, he had been returning to the United States from Australia after being denied admission to go on a walkabout — a tour of the outback imitating the Aboriginal rite of passage — because he had lied about his paralysis. Right after the crash, he realizes he has regained feeling in the lower half of his body and no longer needs his wheelchair. One of the earliest shots of Locke is of him lifting up his arms in the middle of a rainstorm shortly after the crash with an ecstatic look on his face — he believes the cure of his paralysis is a “miracle,” and this moment marks the beginning of Locke’s long spiritual journey. His character arc is the closest we have in the show to a “Robinsonade.”

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?

Locke is among the first to perceive that there is something strange about the island. In a conversation shortly after the crash, Locke tells Jack Shephard:

I’m an ordinary man, Jack, meat and potatoes, I live in the real world. I’m not a big believer in magic. But this place is different. It’s special. The others don’t want to talk about it because it scares them. But we all know it. We all feel it. Is your white rabbit a hallucination? Probably. But what if everything that happened here happened for a reason?

Both Crusoe and Locke, in spite of being everyman characters — one the son of a middle-class merchant and the other a box company employee — achieve heroic stature as island survivalists. Crusoe becomes totally self-sufficient and a master of all trades. Locke becomes the spiritual leader of the group, a wise man with a special connection to the island, which allows him to track, hunt boar, and discover the secrets of the place.

Like Crusoe, Locke also experiences a conversion on the island — but Locke’s is the inverse of Crusoe’s. Soon after he undertakes his exploration of the island, Locke finds a mysterious locked hatch buried in the ground. He keeps this discovery from the other survivors, lying to them that he is hunting when he is in fact spending his days obsessively trying to open it. After his miraculous recovery, Locke is optimistic that there is some greater meaning to the hatch, that opening it will reveal why they are all on the island and provide the final, revelatory answer to his long malaise.

Locke’s optimism that the island has some transcendent meaning — that they are there for a purpose — creates conflict with the other survivors, especially Jack Shephard, the island’s pragmatic surgeon. Jack and Locke are pitted against each other as representing two different sources of authority: respectively, the man of science and the man of faith — a distinction, of course, that would be unfamiliar on Bacon’s utopian island. “The island chose you too, Jack. It’s destiny,” urges John. “All of it happened so that we can open the hatch.” “No. No, we’re opening the hatch so that we can survive,” replies an aghast Jack.

In another striking echo of the miraculous vision in New Atlantis, Locke sees a great beam of light coming from the hatch, convincing him that he is about to get answers to his lifelong quest for meaning. But this seemingly miraculous moment will ultimately give way to despair when Locke discovers the beam’s true cause. The hatch turns out to be home to a research station, inhabited by a man named Desmond David Hume, whose only job is to press a button to avert an unspecified catastrophe that will destroy the world. Locke eventually becomes convinced that the task was a sham, and Hume really an unwitting subject in a psychological experiment. Like his namesake, whose skepticism and latent atheism unsettled the religious convictions of the eighteenth century, the arrival of Hume on the show begins to sow doubt in our hero’s mind. What in New Atlantis was an undoubted miracle becomes a this-worldly scientific experiment in Lost. In a later conversation with Hume, Locke reflects on the beam of light, saying, “I thought it was a sign. But it wasn’t a sign. Probably just you going to the bathroom.”

In Robinson Crusoe, the quest for causes nearly always leads to an unsolvable puzzle, an impasse between equally plausible natural and supernatural explanations. In Lost, too, causation is mysterious. But what is at stake in Lost is not whether we can know the world but whether we have a purpose in it — whether we are here because we are meant to do something, or just by accident. The discovery that the hatch is part of a scientific research station plunges Locke into a spiraling despair, the reverse of Crusoe’s ascent into hope.

As Lost’s castaways discover more evidence about the island, Locke gradually becomes convinced that there is no grand purpose for them being on the island: His cure was not a miracle but the result of a powerful magnetic field; apparent ghosts on the island are probably just a stress-induced hallucination; and all the other signs that they are part of a grand plan were really planted by a powerful group of scientists observing them like amoebas in a petri dish.

Walker Percy, in his mock self-help book Lost in the Cosmos, calls the failure to readjust to ordinary life after an experience of heightened reality a “re-entry problem.” Robinson Crusoe has no such problems upon his eventual return to England in the last section of the novel: He reintegrates happily into English life after decades of isolation, counts his money, and visits friends. But when Lost flashes forward to show us the characters after being rescued from the island and returning home, we see that they have grown even emptier. Jack, the confident doctor once hellbent on leaving the island, has become a shadow of himself, chillingly urging Kate, “We have to go back.”

In the castaway fable of our day, the man of science and the man of faith are not one figure, bound by covenant to God, but two torn asunder. And science has not solved the problem of discerning divine purpose but created a double consciousness that paralyzes us from ever knowing for sure. In the search for meaning, we are rarely satisfied, and are only met with ambiguity. Caught between belief and unbelief, we are all castaways, far from home — and no philosophy will get us back.

Notifications