For years, there have been clear signals that euthanasia providers in Canada may be breaking the law and getting away with it. That is the finding of the officials who are responsible for monitoring euthanasia deaths to ensure compliance in the province of Ontario. Newly uncovered reports reveal that these authorities have thus far counted over 400 apparent violations — and have kept this information from the public and not pursued a single criminal charge, even against repeat violators and “blatant” offenders.

In Canada, medical assistance in dying, or MAID, is regulated by criminal law. Practitioners must comply with federal and provincial criteria or face lengthy prison sentences. Among other requirements, they must carefully assess whether people who request euthanasia are eligible, uphold all the safeguards against abuse, and report each request and each death.

Euthanasia advocates often tout the strictness of these laws as evidence that the safeguards are working. “Like most clinicians that do this work, I’m acutely aware of what happens … if I break the rules anywhere,” says Stefanie Green, a former president of the leading organization of Canadian euthanasia practitioners, on a podcast. “There’s criminal liability sitting in the back of my head, blaring out loud and neon signs: 14 years in jail.”

In Ontario, the responsibility for lighting up those neon signs falls to the Office of the Chief Coroner. Since 2014, that office’s head has been Dirk Huyer, who has publicly boasted that “Every case is reported. Everybody has scrutiny on all of these cases. From an oversight point of view, trying to understand when it happens and how it happens, we’re probably the most robust in Canada.”

But private documents reveal a different side of the story.

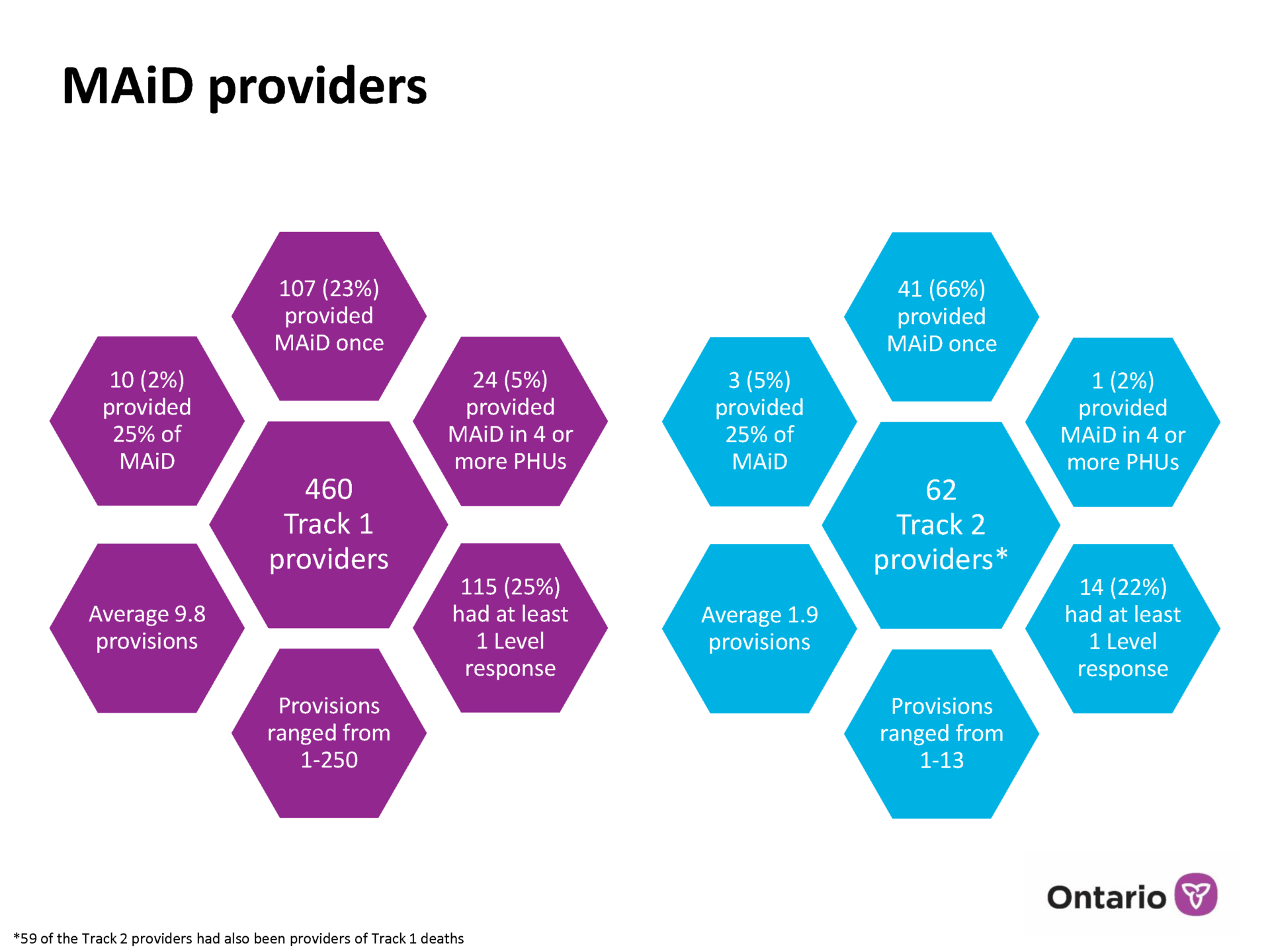

From 2018 to 2024, in presentations held behind closed doors and in reports that were nominally public but garnered little attention, Huyer has shown that his office has identified hundreds of “issues with compliance” with the criminal law and regulatory policies. In 2023, his office raised these concerns for a quarter of all euthanasia providers in Ontario.

Most of the information in these documents, which were shared with The New Atlantis by three physicians who had access to them on condition of anonymity, is being newly made public or reported on for the first time in this article.

“There’s criminal liability sitting in the back of my head, blaring out loud and neon signs: 14 years in jail.”

After more than four hundred identified issues with compliance, ranging from broken safeguards to patients who were euthanized who may not have been capable of consent, Huyer’s office has failed to alert the public or take any steps to prosecute offenders. Whether or not these hundreds of “issues” are in fact violations of criminal law is unclear precisely because none of them have been referred to law enforcement for investigation. Instead, Huyer’s office has deemed virtually all of them as requiring nothing more than an “informal conversation” with the practitioner or an “educational” or “notice” email. Even in one egregious case, in which the practitioner was found to have violated multiple legal requirements, and which Huyer himself described as “just horrible,” his office reported the case only to a regulatory body instead of the police.

Oversight of euthanasia is meant to be “protecting vulnerable people from abuse and error,” according to the Supreme Court of Canada. Instead it is protecting euthanasia providers from their abuse and error coming to light.

2016 to 2017: Compliance problems with Ontario’s first 100 euthanasia deaths

In June 2017, a year after euthanasia was legalized in Canada, Dirk Huyer and two co-authors published a paper in the journal Academic Forensic Pathology that examined the first one hundred euthanasia deaths in Ontario based on reports to his office by euthanasia providers. The paper shows early warning signs that providers were not complying with the federal criminal regulations for MAID.

“The MAID regulations require clinicians to notify the pharmacist of the purpose of the MAID medications before they are dispensed,” the paper notes. “However, some physicians listed that they did not abide by these regulations.” Only 61 percent did. Federal legislation at the time also required a 10-day waiting period between the request for euthanasia and the administered death to ensure that patients really did wish to die, a safeguard that could be waived only if the patient was approved and on the verge either of losing capacity to consent or of imminent natural death. Yet according to the paper, euthanasia providers recorded expediting deaths for reasons including not only loss of capacity or imminent death but “persistent requests” and “inconvenient timing of the death in relation to other familial life events.”

As later private reports from Huyer’s office demonstrate, these sorts of problems with compliance never went away.

2018: Huyer speaks at a webinar to Ontario nurse practitioners

In an October 2018 memo to all Ontario health care practitioners, Huyer announced that his office would implement a new system “to respond to concerns that arise about potential compliance issues.” That is because “some case reviews have demonstrated compliance concerns with both the Criminal Code and regulatory body policy expectations, some of which have recurred over time.”

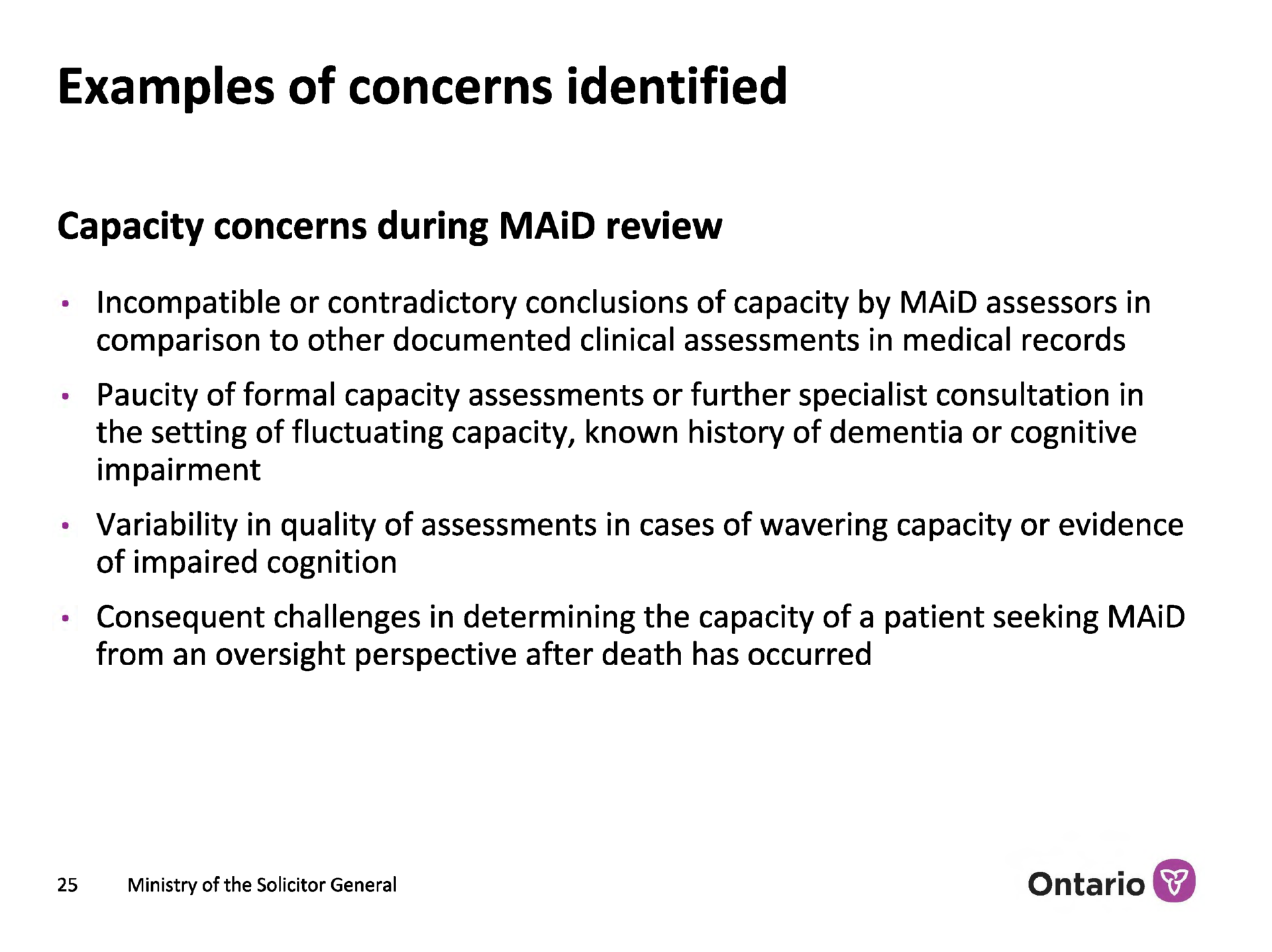

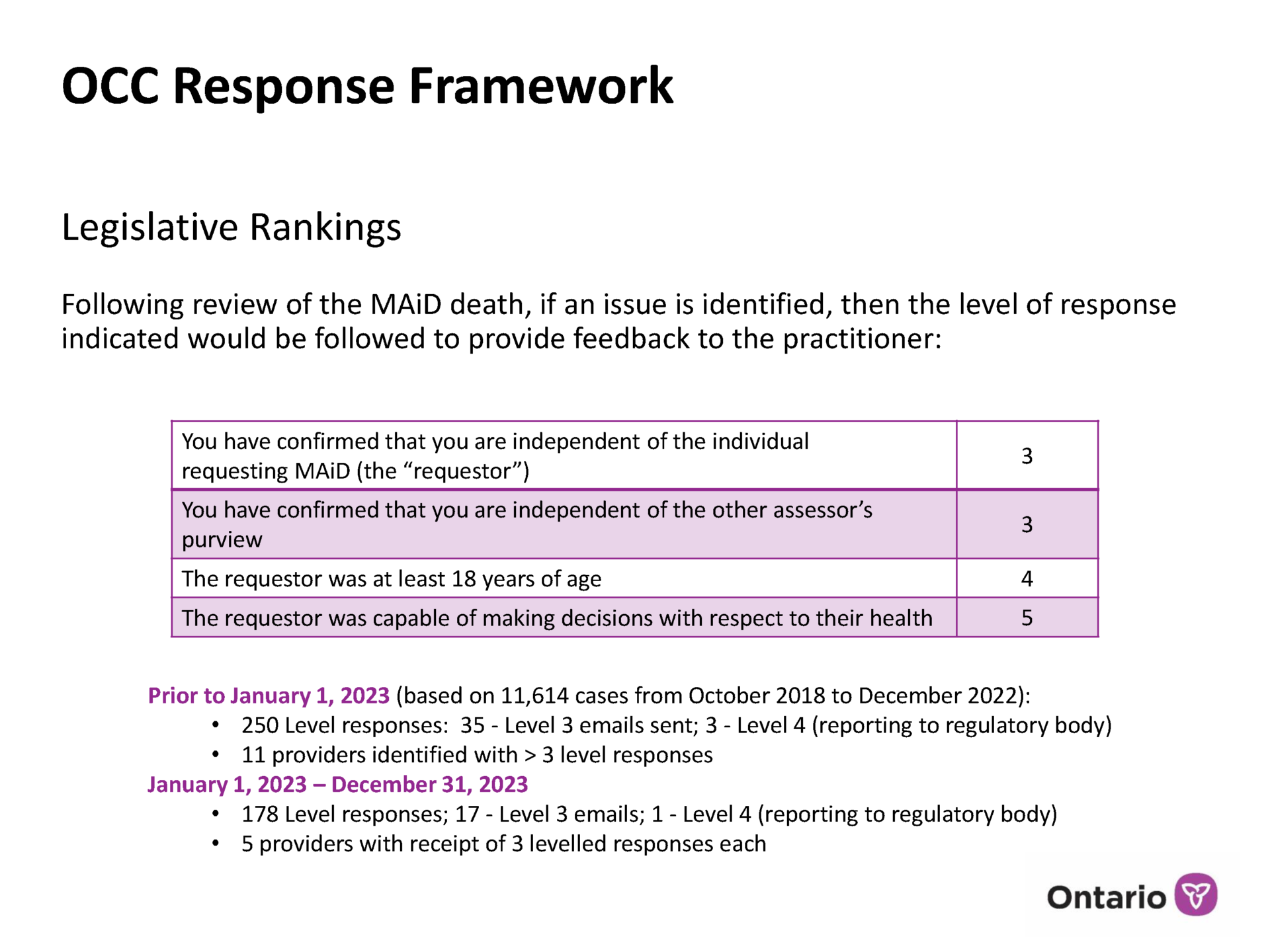

In the new system, each compliance issue gets assigned a “level” of severity, with 1 being the least severe and 5 the most severe, along with an action the Coroner’s Office will take to address it, from an informal conversation (Level 1) to a report to the police (Level 5).

“We see a pattern of not following legislation, a pattern of not following regulation, and frankly we can’t just continue to do education to those folks if they’re directly repeating stuff that we’ve brought to their attention.”

At a private monthly webinar of Ontario nurse practitioners in December 2018, available as an unlisted video on YouTube where it has been viewed only a few dozen times, Huyer further explains the purpose of the system: “making sure the proper legislative rules were followed, the College [of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario] policies were followed, the diagnosis makes sense to be meeting criteria, and that the full data was reported.” Compliance with these standards, Huyer says in the presentation, has overall been excellent: “We don’t see problems in the vast majority of cases.”

But, he notes, there is a “very small handful” of practitioners who “are not responding to our educational input and are maintaining the same practice repetitively. And so we see a pattern of noncompliance, we see a pattern of not following legislation, a pattern of not following regulation, and frankly we can’t just continue to do education to those folks if they’re directly repeating stuff that we’ve brought to their attention.”

So what actions are taken instead to respond to these practitioners who repeatedly break Canada’s criminal law? The most severe case Huyer notes is instructive:

One is a blatant situation that’s published through the College of Physicians and Surgeons of just being completely unprepared and bringing wrong medications. They brought scopolamine and Ativan. Those were the drugs that the clinician brought to the home to administer MAID. And it was just horrible. It was horrible. The family, and I’m talking about what’s public, so this isn’t anything non-public, the family and the deceased person suffered tremendously.

The case occurred in 2017, before Huyer’s office implemented the level system for response. But he notes that they have never reported a case to the police. Instead, they treated this case in accordance with what would become Level 4: reporting it to the regulatory body, the College of Physicians and Surgeons. The College in turn conducted an investigation, concluding it was “disturbed” by the practitioner’s manifold failures — lack of preparation, ignorance of MAID policies and procedures, use of the wrong drugs, and leaving the dying person’s bedside for over two hours to get further drugs, as the ones she had been using did not fully work. The physician who was tasked by the College with offering an independent review of the case “was of the view that Dr. Tjan” — the euthanasia provider in this case — “continued to underestimate the magnitude of providing medically-assisted death and the responsibility attached.”

And yet the practitioner, Dr. Eugenie Tjan, remains a licensed physician in Ontario. The College did prohibit her from practicing euthanasia, but kept her license to practice palliative care, as long as it is under the supervision of another physician.

If this most “blatant” case of violating Canada’s criminal law on euthanasia did not trigger a criminal investigation, no wonder the compliance concerns that Huyer’s office identifies have received so little public attention. Meanwhile, out of sight, the number of concerns continued to rise.

Asked by email why none of these incidents of noncompliance merited referral to law enforcement, Dr. Huyer replied that the responses “are case specific and we look at each case wholistically.” If his office believes that “the MAiD process was overall appropriate” and “the issue was isolated,” then “we do not notify other organizations, e.g., regulatory bodies or law enforcement.”

However, “for a smaller number of providers there were potential patterns of concern,” and “this is why we introduced the levelled response process and shared it publicly and with providers and assessors.”

Additionally, he noted, “We do have regular intersections with Ontario regulatory bodies and law enforcement organizations relating to MAiD and no concerns have been expressed regarding our review and leveled response approach.”

2020: Huyer’s presentation “Monitoring and Oversight of Medical Assistance in Dying in Ontario”

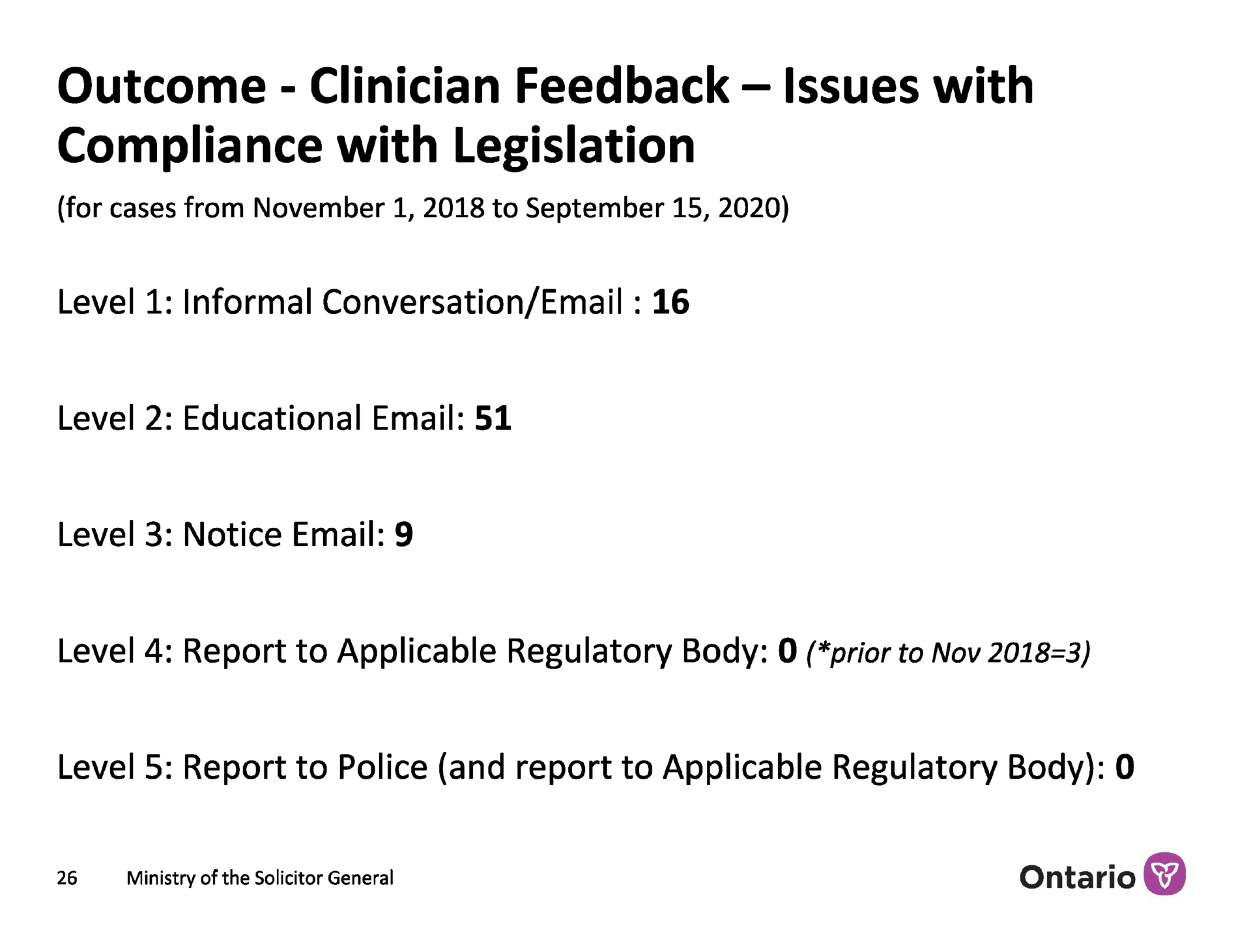

In September 2020, Dr. Huyer gave a presentation on “Monitoring and Oversight of Medical Assistance in Dying Ontario” at a symposium of the Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers. According to slides The New Atlantis has obtained of this presentation, Huyer’s office identified 76 “issues with compliance” since it had implemented the level system in late 2018, roughly a two-year span. All of these compliance concerns were assigned one of the first three levels of severity, triggering at most a “notice email” to the practitioner.

Yet the concerns were not insignificant. They fell into two categories, the first of which was problems with “documentation and compliance with legislation.” This included “poor/no completion of accompanying assessment notes” on how eligibility for euthanasia was decided by the clinician. It also included “missing documents,” and “partial completion / no completion of federal reporting requirements by clinicians.”

That this information is missing or incomplete in some cases should be a very serious matter. After all, the mandatory reporting exists to establish that the requirements under criminal law for ending thousands of lives were met.

One of those requirements at the time (it was removed in 2021) was a 10-day reflection period between a patient requesting MAID and being euthanized. It was put in place as a safeguard for people at their most vulnerable who might change their minds and choose life instead of death. Among the compliance concerns that Huyer’s office identified, we read “counting of 10 clear days of reflection.”

The second category of concerns was about whether patients had the necessary capacity to consent to be euthanized. These problems included “incompatible or contradictory conclusions of capacity by MAID assessors in comparison to other documented clinical assessments in medical records,” a “paucity of formal capacity assessments or further specialist consultation” in cases where patients had a “known history of dementia or cognitive impairment,” and “variability in quality of assessments in cases of wavering capacity or evidence of impaired cognition.”

Compounding these problems for the Coroner’s review process is that, after the patient’s death, it is very difficult and perhaps impossible to find out whether a patient in fact did or did not have capacity to consent to be euthanized. In his presentation, Huyer notes “consequent challenges in determining the capacity of a patient seeking MAiD from an oversight perspective after death has occurred.”

2024: Huyer’s presentation “Lessons Learned from the Coroner”

At the 2024 annual conference of the Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers, held in May, Dirk Huyer gave another slideshow presentation, “Lessons Learned from the Coroner,” providing more detailed information up through 2023. The slides The New Atlantis has obtained of this presentation show that for 2023 alone, Huyer’s office identified 178 compliance problems — an average of one every other day — bringing the total since implementation of the level system to 428. (This existence of the presentation was first revealed in October by the Associated Press, but it reported on just one slide.)

Out of all those 428 compliance issues, spanning roughly a five-year period, only four cases triggered a report to a regulatory body. All others were deemed lower-level offenses, and not a single case was reported to the police.

The frequency of these problems is striking. Consider the following findings:

One area of persistent concern is with the legally mandated safeguard of a waiting period. Since 2021, when MAID legislation was expanded to include people with non-terminal conditions, a minimum period of 90 days has been required for this group between when the patient is first assessed and when he or she is euthanized. The intent is to ensure that there is enough time to explore help and treatment options, and that patients are not rushed toward death. This assessment period may be shortened only if the patient’s loss of capacity to provide consent is imminent.

In 2023, a quarter of all euthanasia providers in Ontario received at least one response from the Coroner’s Office about a compliance issue.

We learn from the Coroner’s public report that the assessment period took less than 90 days for 13 percent of euthanized people whose conditions were not terminal. Theoretically, it could be that in all these instances the patient’s loss of capacity was imminent. However, we know this is not the case. In a May 2024 memo to Ontario euthanasia practitioners, the Coroner’s Office describes the “case example” of a person suffering from stroke, neurocognitive disorder, and vision loss whose assessment period was 71 days. The memo notes as a “learning point” both that the counting of the 90 days began too early in the process and that “the assessment period was incorrectly shortened” — the person was not imminently losing capacity to consent. Rather, the date of death was chosen by the person’s spouse “based on the spouse’s preference of timing.” Parenthetically, the memo notes that this “raised considerations regarding potential impacts to voluntariness and coercion.” Notably, this public report — unlike Huyer’s private presentations — did not identify whether physicians failed to comply with legislation.

Canada’s criminal law on euthanasia states that “Medical assistance in dying must be provided with reasonable knowledge, care and skill and in accordance with any applicable provincial laws, rules or standards.” And yet the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario has decided that euthanasia practitioners’ ongoing failures to comply are best resolved through emails. The highest-level response it routinely applies, Level 3, happens “when there are identified issues with statutory requirements and/or repeated practice issues.” The Coroner’s Office in these instances sends a “notice email.”

According to the Chief Coroner’s rubric, euthanizing a minor would not lead to an immediate police report.

Level 4 is applied in cases of statutory requirements (such as “eligibility requirements”) and cases of “significant” issues with practice. This level triggers a report to a regulatory body. Huyer’s 2024 presentation offers as a hypothetical example the euthanizing of a minor. In other words, according to the Chief Coroner’s rubric in the presentation, and to the Coroner’s public website, last updated in May 2024, euthanizing a minor would not automatically lead to a police report.

However, asked for comment on which cases would warrant referral to law enforcement, Dr. Huyer replied: “Serious not meeting criminal code — i.e. under 18,” meaning euthanasia of a minor. In response to a follow-up request to clarify the contradiction between this statement and the presentation, Huyer wrote: “your question prompted my reflection and in fact I believe that I would report this to law enforcement (in other words I believe we should revise our levelled response for this concern — this occurrence has not happened in Ontario).”

Huyer’s office flagged only one Level 4 incident in 2023. We do not know what it is, but another incident, spanning from 2022 to 2023 and involving the regulatory body, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, is again instructive. This is the case of a woman whose son brought before the College a complaint that she was improperly assessed before being euthanized and that the roughly 4 weeks between her MAID request and her death was not enough time to understand her condition, since she was not in any physical pain.

Upon reviewing the case, the College’s investigative committee decided to not take any action. The committee reasoned that “the Coroner’s office … is responsible for reviewing each case to ensure that all the proper checks and balances were in place and that the process was followed properly,” and it “did not find any concerns.”

The Chief Coroner’s self-understanding — that his office is able to track every case and report every problem — seems to be shared by the College of Physicians and Surgeons. But the problems the Coroner’s Office does find, and yet does not usually share with the public, are evidence that the system is not working for the protection of the vulnerable.

Asked for comment on why the findings are not shared with the public, Dr. Huyer disputed this claim: “We share regularly through Health Canada and our presentations. Nothing was confidential — we are working to more systematic reporting.” In a follow-up, he added: “we have widely shared our response framework and have shared the number of levelled responses to a number of media outlets and at conferences and meetings over the past years.”

Huyer’s response is belied by available information. Some of the information in this article was previously public, as noted throughout. But in many cases it was public in name only, as it remained at obscure online locations or available only to MAID professionals, and had not been previously reported on in the media. The latest report on the level system publicly available on the Ontario Coroner’s website describes only “the first two years of medical assistance in dying” and offers no information on how many cases have actually been reported, or on any of the specific cases of noncompliance described in this article. Finally, searches on multiple key phrases confirm that the 2020 and 2024 slideshow presentations at the center of this article had never been released publicly.

If it seems like Canada’s oversight of euthanasia should receive closer public, medical, and law enforcement scrutiny, that is a concern shared by at least two members of Ontario’s MAID Death Review Committee — an advisory group formed by the Chief Coroner to help improve the MAID system in the province — to whom I spoke for this article.

Speaking as individuals, both urged a thorough investigation of cases flagged by the Coroner’s Office. “In my opinion, any violation of the MAID law, considering that it’s a criminal law, should be reported to the police and to the College — as a matter of principle — and should certainly be investigated by an independent prosecutor…. I don’t know why that hasn’t happened,” said Trudo Lemmens, a law professor at the University of Toronto, in a video call. “It’s a serious issue. I mean, this is a criminal law and I’m worried that the lack of referring for prosecution and for investigation by the College of Physicians and Surgeons reflects a kind of normalization of MAID as some kind of inherent beneficial practice.”

Dr. Ramona Coelho, a family physician from London, Ontario, and a senior fellow of the Macdonald–Laurier Institute, a public policy think tank, wrote by email that “it has been distressing to learn that some authorities, well aware of non-compliance with the law, did not publicly report them.”

The reason the public has been left in the dark about Canadian euthanasia providers’ noncompliance with the law is simple: the authorities have decided there is nothing to see.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?