Once in a while you find yourself in an odd situation. You get into it by degrees and in the most natural way but, when you are right in the midst of it, you are suddenly astonished and ask yourself how in the world it all came about.

Growing up is a bit like that. The process of development that brings us from zygote to maturity is nothing if not the most natural and gradual series of events, and yet, at some point, often in adolescence, we are bound to look around and notice that the whole thing is exceedingly strange. How did I get here and why? What sort of a thing am I, anyway? This fundamental human experience of wondering and questioning existence is the starting point of so many journeys: into the mind, for a philosopher; into the workings of the world, for a scientist; into the clues of the past, for a historian or anthropologist; into the realm of the spirit, for the religious; into the unknown, for an explorer. Thor Heyerdahl’s life would be an effort to embark on all of these at once.

That sense of wonder found Heyerdahl drifting on a raft of balsa wood in the doldrums of the Pacific, listening to a squawking parrot and the low murmuring of a bearded Swede reading Goethe in the shade. The question that had driven him to such lengths had met him years earlier, in 1936, at dusk, on a little island in the South Pacific, over two thousand miles to the southeast of Hawaii, called Fatu Hiva.

Heyerdahl and his wife, Liv, had been living there for a year, collecting biological specimens and cultural objects as amateur scientists. Many nights they would sit around a beach fire with locals as the sun dropped into the sea. On this night, Liv remarked on how odd it was that the breaking waves only ever hit the island from the southeast. Together they looked in the direction those waves had traveled: thousands of miles of open ocean separated this spot from South America. Tei Tetua, an old keeper of local tradition, stirred the fire and nodded in the direction of the waves. It was from there, he said, that Tiki, son of the Sun, had come to settle these islands.

Retiring to bed later that night, hearing the rush of those waves hitting the beach, Heyerdahl’s imagination was alight. Tiki came from the rising sun, Tetua had said, the direction of Peru. Of course, in the legend of the Incas, there was a Tiki too: Kon-Tiki, also called Viracocha, was the Incan creator deity. Could it be that these were the same god? What if, against the odds and against the consensus of the experts, these islands were first not settled from Asia, but by voyagers from the New World? Unable to contain his excitement, he turned to Liv and whispered, “Have you noticed that the huge stone figures of Tiki in the jungle are remarkably like the monoliths left by extinct civilizations in South America?”

As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong.

The question Heyerdahl had thrust into the spotlight with some forty feet of balsa wood and a handful of sunburnt Scandinavians — namely, whether an ancient journey really had been made between South America and Polynesia — would take seven decades of anthropology, botany, linguistics, archaeology, genetic analysis, and computer science to answer. The story of the world’s argument over an amateur scientist’s hunch came to its stunning conclusion last summer, when Alex Ioannidis, a computational geneticist at Stanford, led a team of researchers on the first truly definitive study of Polynesian–South American admixture. It is a story of a scientific endeavor as complex and abundant as the world it sought to study, born out of the most deeply human desires.

As the rainbow spans the horizons,

So the canoe of ‘Ui-te-rangiora crosses the open seas between.

It was the scorn of his contemporaries that drove Heyerdahl on his preposterous journey. “No! Never! … You’re wrong, absolutely wrong,” said one New York museum curator to the idea of a prehistoric journey from South America to Polynesia. Margaret Mead, the legendary ethnologist, dismissed the idea. “Sure, see how far you can get yourself … on a balsa raft!” challenged the anthropologist Herbert Spinden. So he did.

Just as significant, though, was Heyerdahl’s feeling that, to answer questions like these, science needed to break out of siloed specialization and speak across disciplines. His own areas of study had been biology and geography, but “to solve the problems of the Pacific without throwing light on them from all sides was … like doing a puzzle and using only pieces of one color.”

It was not within the powers of one ambitious amateur to fill in that puzzle, but he had the right idea. Answering the biggest questions did not come down to a single computation or experiment, but to evidence as varied as the content of ancient songs, the historical travels of the domestic chicken, the sound of the word kumala, and, finally, the genetic codes of modern inhabitants of Polynesia and Latin America. It took the combined tools of many avenues of inquiry to yield the truth about pre-historic trans-Pacific travel.

And this truth has yielded many more. No one could have guessed that the suppositions of a wannabe anthropologist with an overactive imagination would one day have anything to do with the development of genomic tools that can be used to help understand a devastating pandemic. But all of this in due course; we left Heyerdahl sitting on his raft.

The handle of my steering paddle thrills to action,

My paddle named Kautu-ki-te-rangi.

It guides to the horizon but dimly discerned….

To the horizon that ever recedes, …

The horizon not hitherto pierced.

When German vessels started belching out black-clad Schutzstaffel onto the quay in Oslo in 1940, Heyerdahl was pecking away at another novelty of his theory in faraway Canada. In order to explain the staggered development of Polynesian technologies like the stone-lined earth oven, the adze, and even the canoe, he had begun to suppose that the Pacific islands had been reached not only by ancient people in Peru, but by indigenous travelers from what we now call British Columbia, too. The beginning of the Second World War found him digging around in the dirt somewhere near Vancouver.

A patriot and ardent anti-Nazi, Heyerdahl returned to Europe to join the resistance. At a training camp for freedom fighters in England, he met other Norwegian resisters, including Torstein Raaby, a telegrapher for the Secret Intelligence Service, and Knut Haugland, one of a small group of special operations troops who had carried out the extremely dangerous sabotage of a heavy-water factory at Rjukan, Norway. At that time, the physicist Werner Heisenberg required heavy water (water with deuterium, a heavier hydrogen isotope) to stabilize his experiments in refining uranium for a Nazi nuclear bomb. Haugland and company succeeded in delaying the progress of the bomb, and the Nazi empire fell before Heisenberg saw success.

When the war was over, Heyerdahl renewed his efforts in anthropology and began looking for funds and a crew for a major expedition. His brothers in arms Raaby and Haugland were among the first recruits. They were joined by Herman Watzinger, an engineer, Erik Hesselberg, a navigator, and Bengt Danielsson, a sociologist and the only Swede on the otherwise Norwegian crew. Heyerdahl, who was a great storyteller and self-promoter, lobbied New York businessmen, outfitting companies, and even the U.S. War Department to support his venture. The corporate figures saw this as an opportunity for advertising (National Radio Company promoted the use of one of its units on the journey) and the War Department saw it as a chance to test experimental equipment, like new Primus stoves and waterproof matches.

Modeling their vessel on old Spanish conquistador illustrations of Peruvian rafts, the Scandinavian explorers made their way toward Lima and began construction. There, in the navy dockyards, with modern equipment and support from locals, they reconstructed the historical craft. The vessel was composed of nine thick balsa logs, with a central timber of forty-five feet, and logs to each side shortening symmetrically by a few feet as they moved to the edge of the raft. The starboard and port sides were thirty feet each, giving the raft a sort of dull bow. A central mainmast supported one mainsail and a topsail, and in the stern a wooden block anchored the large steering oar. This was the sort of vessel reported on the exploratory journeys of Francisco Pizarro. Heyerdahl and crew christened their raft Kon-Tiki, and on April 28, 1947, they were towed out into open water and wished farewell. Soon, the Kon-Tiki was tossing like a cork in the stormy, wine-dark sea.

The journey afforded no shortage of adventure. There were encounters with whale sharks of impossible size, battles with wind and waves, and sublime nights when the waters were still and lit all around with the phosphorescent life of the deep. One morning, Raaby awoke to find a companion in his sleeping bag: a toothy, ugly snake mackerel, till that moment considered to live only in the depths of the sea, and never before seen alive. The crew would fish for food, catch sharks for sport, and radio reports back to the mainland on weather and position. They would pass the time with poetry and contemplation of the stars that had guided the seamen of old.

For their part, the Kon-Tiki crew used a sextant and maps of the Pacific to mark their course. How the ancient South Americans navigated only by the skies no one knows for sure. Little is known of these navigators at all, but it is believed that as early as 100 b.c. Ecuadorian voyagers were making their way along the coast northward toward Mexico and southward toward Chile. By 700 a.d., South American metallurgy started showing up on Mexico’s western coast, carried there by balsawood rafts of the sort used in the Kon-Tiki expedition. When Spanish conquistadors arrived, they were surprised to find these sturdy seagoing vessels on their trade routes.

But Heyerdahl and crew were not hugging the coast, they were setting out into open water. Strong and buoyant as it is, one trouble with balsa is that it takes on a good deal of water. Each day the raft absorbed more moisture and sunk imperceptibly lower in the ocean. Driving a knife into the timber to see how deeply the wet had penetrated, the crew estimated they would reach Polynesia just when the raft would become too waterlogged to go on.

By the time they were far out enough to find themselves outside normal shipping routes, and far from any thought of land, a new feeling settled on the ship. It was as if there were no other people in the world, and real peace and freedom seemed to descend from the heavens themselves. “To us on the raft the great problems of civilized man appeared false and illusory — like perverted products of the human mind. Only the elements mattered. And the elements seemed to ignore the little raft,” wrote Heyerdahl. Such romanticism on a scientific voyage! But anyone who has taken a prolonged retreat into nature will recognize the sentiment — a feeling that bonds seafarers across cultures and times.

What makes the marvelous Kon-Tiki book so engaging, such that it still finds many devoted readers today, is not just the peril and adventure, but a sort of scientific aesthetic that feels like something from a bygone age. Take Heyerdahl’s description of various plankton specimens — creatures that “looked like fringed, fluttering spooks cut out of cellophane paper, while others resembled tiny red-beaked birds with hard shells instead of feathers. There was no end to Nature’s extravagant inventions in the plankton world; a surrealistic artist might well own himself bested here.” When Heyerdahl writes about botany, marine biology, or anthropology, his words thrill with the sense of exploration, the wonder of new creatures and new worlds unseen.

On August 7, 1947, 101 days after embarking, our Scandinavians reached their destination, to much jubilation among themselves and the Polynesian communities who welcomed them. Heyerdahl took an understandable pride in the endeavor and set about straightaway in using it to push his theory, publishing Kon-Tiki just the next year. He admits in an appendix that the journey by no means confirmed his full theory, but it showed that such a journey was possible with the materials available at the time — and that was not nothing.

The sea seethes,

The sea recedes,

It appears, the land appears

And Maui stands upon it.

In the scientific community, the journey caused an immediate stir. Among the first recorded reactions is one from Te Rangi Hīroa (also known as Peter Buck), the great Maori physician and anthropologist. “That Kon-Tiki business” made him laugh, according to a local newspaper report in New Zealand. Hīroa had developed a theory of his own, which he had described in his 1938 book Vikings of the Sunrise. In it, he used Polynesian folk stories to chart a path taken by his people across the vasts of the Pacific.

Heyerdahl had been intrigued by these stories too, and he found it remarkable that islands far more distant from one another than, say, London and Jerusalem could maintain a similar language, culture, and set of stories. Indeed, even the genealogies recited among the old memory keepers of the various corners of the Pacific tracked with one another. This made Heyerdahl believe that the settling of those islands was relatively recent, and, indeed, from the direction of the Americas.

When it came to the settlement question — whether Polynesians had come from South America or Asia — Hīroa had the evidence on his side, and superior knowledge of the lore. He poked fun at the linguistic proofs of people like Heyerdahl, who tried to show the similarity between “Tiki” and “Kon-Tiki.” Although mysteries remain in the settlement of the Pacific islands, most scholars now believe that it was thanks to the Polynesians’ truly remarkable skill in seafaring that an area more than four times the size of Europe was settled in the Pacific, and that these Polynesians originally came from the west by way of Micronesia and Melanesia. They descended from the seafaring Austronesian people, from Taiwan and Southeast Asia, who had been journeying for the last few thousand years in the western Pacific and Indian Ocean. Around 1000 b.c., a subgroup of the Austronesians called the Lapita began journeying further east to islands like Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. Subsequent waves of migration over many centuries reached the Marquesas Islands, Easter Island, and Hawaii, and, by about 1200 a.d., New Zealand.

That Heyerdahl was wrong about settlement, though, does not mean that he was wrong that South Americans had made the journey westward to Polynesia. He was certainly wrong to think that the South Americans who made the journey were a race of pale, long-bearded men. He adapted this idea of a semi-divine, fair-skinned race from the Spanish versions of native Peruvian myths, but there is no other evidence of the existence of such a people, and many have seen a racist underpinning in the notion that only a white culture could have made the journey.

Hīroa had avowedly taken up the task of making an anthropological survey of the islands out of a measure of Polynesian pride; he wanted the world to know what he knew, that the people of these islands were among the greatest voyagers in history. His approach took into account the various kinds of material culture and botanical evidence of the islands. Both he and Heyerdahl were intrigued by botanical questions. The palm coconut and calabash posed problems, since they were non-native species with a long history of Polynesian cultivation, but the greatest mystery was the sweet potato, and its presence since at least the thirteenth century led Hīroa to embrace a fringe theory: Some Polynesian adventurer had traveled over four thousand miles of open ocean in a canoe to South America during the Middle Ages. Shrugging off Western explanations that undercut the voyaging prowess of the Polynesians (some anthropologists had proposed that now-sunken archipelagos or a land bridge had made the settlement of the Pacific possible), Hīroa found nothing implausible about such a canoe journey, even as he thought the Kon-Tiki story ridiculous. In Vikings of the Sunrise he mentions his idea almost as an aside, as if it were an obvious fact.

“ … Resplendent Day,

Bright Day.”

Behold! It became radiantly light!

First then his gaze fell upon the waters surrounding him.

In the beginning, there was Io-matua, who dwelled in Tikitiki-o-rangi, the highest of the twelve heavens. He presided over the void and the night, and there was no light in the universe until he spoke: “Night! Become Day-possessing Night!” Thus did light enter the universe and night was separated from day. Io, the parentless, became the parent of all the gods, of all the creatures of the Earth, and of humankind.

This is the creation myth that was passed down by the priests of the Whare Wananga in New Zealand. Some have wondered whether this pure, supreme deity was a result of native myths incorporating Christian ideas, or if it truly has an authentic Polynesian origin, as the followers of the Io cult had said. The question is not settled, but the important element in the story is what it shares with the various other creation myths of Polynesia — that there is a direct genealogy from the divine to humanity.

Te Rangi Hīroa credited the idea of divine origin with spurring the Polynesians across the open seas of the Pacific. It was their confidence that they were children of the gods that instilled in the ancient navigators the faith that they could make their improbable journeys. Modern persons, Hīroa points out, might congratulate themselves on their wisdom in understanding their descent from apes, but a Polynesian could call upon his ancestors and reach the gods. This is why Polynesians kept such detailed and accurate genealogies, Hīroa suggests, as ways of both telling history and of claiming divine inheritance. Lineages terminated in primeval parents with names like Void, Dawn, Gloom, Thought, and Conception. While the drive to explore was surely motivated by the need for resources and space, it was also deeply spiritual. Chasing the horizon was a practical necessity as well as a sacred calling.

When a Polynesian chief felt this call to go journeying, Hīroa explains, he would first look to increase crop yields a year in advance, gathering the food and resources needed for a voyage. Next, he would take his master craftsman into the woods, and together they would select the two tallest, sturdiest trees they could find, fell them, and bring them back to the village. These trees would form the double hulls of the classical Polynesian seagoing vessel, whose low draft made it fast and agile, capable of bearing through extremely rough waters. Between the two hulls would be laid a slatted deck and a fore and aft mast supporting one large sail each of matted screwpine fronds. The vessel would feature a large steering oar, and smaller oars for propulsion in low wind. The hulls would be decorated with carvings of sea turtles, birds, or other spiritual symbols. As they went about their work, craftsmen would sing songs to the god of beauty and the forest, Tane, asking him to guide their hands precisely in planing the canoes or lashing on the deck boards with sennit.

On the day of the journey’s beginning, everyone nearby would gather to throw a feast and send the vessel on its way, packed with rations of dried fruits, fish, and live chickens. The craft was made to drink seawater as a kind of consecration and was set upon the ocean as if on an altar. The boat itself sometimes had a small altar upon which prayers would be offered throughout the arduous and uncertain journey.

At sea, the navigator would look to the stars for guidance. Without sextant or maps, he would have spent many years committing the night sky to memory. Using the setting and rising points of the sun as cardinal markers, he would divide the dome of the sky into sixteen equal parts, and, by watching where a given star appeared at its rising, would know in which direction the vessel was bearing. On the famous James Cook voyage of the eighteenth century, a Polynesian navigator named Tupaia was brought on board and shocked the Europeans by being able to point exactly in the direction of Tahiti, with no map, no matter where in the ocean they were. By noting how the clouds would pile up, feeling the change in the steepness of the swells, and noting the flight of birds, these ancient navigators could also detect land that was well out of sight.

Imagine these sailors on the open sea, a thousand miles from any shore, aiming for little pinpricks of land, huddled about and hushed on an especially clear, calm night, feeling all around them the immensity of sky and sea. In their eyes would have shown the untainted, crystal-set blackness of the cosmos, the splash of the Milky Way arching overhead.

Hoist up the sails with the two crossed sprits,

The two-sprit sails that will bear us afar.

Steer the course of the ship to a far distant land,

Sail down the tide with the wind astern.

Hīroa’s Vikings of the Sunrise, important contribution that it was, contained mysteries his account could not resolve, such as the matter of the sweet potato. Its presence, along with that of other non-native flora, including the calabash (or bottle gourd) and the soapberry, were tantalizing suggestions about South American–Polynesian exchange. Each of these plants is native to South America and exists in Polynesia only in cultivation. Much of the debate over pre-historic seafaring has centered on the question of how these plants made their way across the Pacific: by natural means, or by way of human journeying?

As recently as 2018, a genetic study in Nature claimed to establish that the sweet potato had arrived in Polynesia likely by sea currents more than 100,000 years ago, long before humans. The study sparked passionate debate, not least because some took it to be the last nail in the coffin of theories that South Americans and Pacific Islanders somehow met in prehistoric times: “It removes the last remaining potential evidence for contact,” said one scientist. Others objected to its methods or proposed alternate theories. And there was still the linguistic issue of the name for the sweet potato. How did Polynesians have the word kumala that sounded so much like the word cumal of the Cañari in Ecuador?

Scientists have also wondered about the existence of the non-native chicken in Peru, speculating that Polynesian seafarers had dropped it off before returning home. A 2014 genetic study appeared to show European ancestry for the chickens, which would again cast doubt on pre-Columbian contact between the peoples. A 2007 genetic study of chickens on the Arauco peninsula of southern Chile, however, indicated that the chicken had made it to South America from Polynesia at least a century before Columbus.

In 1998, when Thor Heyerdahl was still out there somewhere digging up the remains of ancient civilizations, the Independent published an article covering a recent genetic study of bones from Rapa Nui, or Easter Island. “DNA shows how Thor Heyerdahl got it wrong,” ran the headline. “Sorry, Thor,” the article said, Easter Islanders came from Asia. Erika Hagelberg, the evolutionary geneticist upon whose study this article was based, felt compelled to correct the record, submitting a letter to the newspaper in 2011 titled “Heyerdahl was right.” “My DNA studies have shown that a few bones of prehistoric Easter Islanders contain genetic markers that are the same as those of modern Polynesians,” she wrote. “But some features of the ancient buildings in Easter Island suggest South American cultural influences. It is clear that the actual physical presence of South American people in Easter Island cannot be ruled out until we have looked at the DNA of a much larger number of archaeological bones of different ages and from different locations in the island.” Hagelberg was not claiming that Easter Islanders came from anywhere besides Asia, only that her study did not disprove such a thing. So in what way was Heyerdahl right? Inasmuch as he had proved that ancient peoples could sail westward on the Pacific by raft.

Hagelberg would have to wait a while for that much larger sampling of DNA, when she joined Alex Ioannidis on the monumental study published last summer. Previous studies had been conducted on limited samples, typically from Rapa Nui, which was seen as a likely point of contact, but this study was the first to engage in a genome-wide study on other Pacific islands. This high-density genome-wide analysis was conducted with 166 Rapanui individuals and 188 other Pacific islanders.

What Ioannidis’s team found drew together the many threads of the last decades; it settled one huge question and opened a great new vista of research. The notion that had received so much scorn was now verified. It has now been demonstrated that Polynesians and Native Americans have a shared history in the Pacific. Long before the days of Columbus, indigenous navigators sailed a distance greater than that which separated Spain and the New World.

Whether these navigators were Polynesian or South American, we do not know. Remarkably, though, it was discovered that sequences typical of the Zenu people of the Colombian highlands were present in the DNA of people from Rapa Nui and other islands, and that these sequences are associated with the older, Polynesian component of the genomes studied, not with the European component.

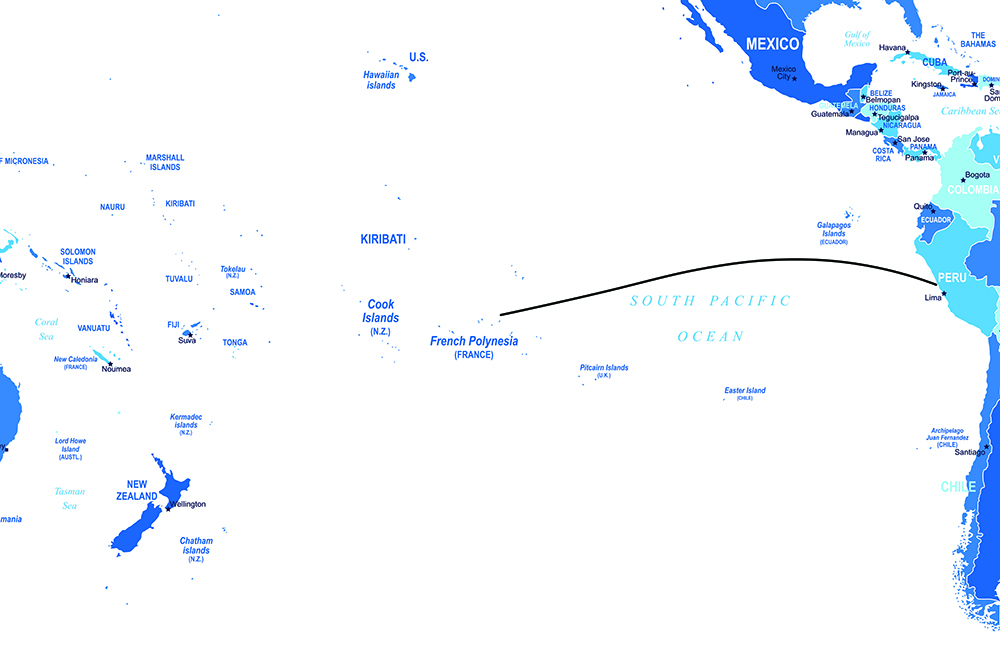

This finding fell into place with several of the important points of the longstanding debate. Some similarities had been noted between the famous statues of Easter Island and those of San Augustín in Colombia, but more significant was the linguistic affinity between the Polynesian word for sweet potato, kumala, and the Cañari word for it, cumal, which pointed to north of Peru. This fits with the likely starting point of such a journey, which would have had to have come from northern Peru, or further north still, since there is no timber in the deserts to the south. It was there, in the north, that South Americans would have been making their great balsa raft voyages to Mesoamerica from 600 to 1200 a.d., and it was around the end of that period that the mixing of Polynesian and South American genetics was discovered to have happened (1150–1230). Studies of oceanic currents show departures from Ecuador or Colombia to be most likely to reach Polynesia and, what is more, to arrive at Fatu Hiva, exactly where Heyerdahl was when he first imagined the journey.

It is possible that when Polynesians reached Fatu Hiva, which would have been a later discovery on their eastward journeys across the Pacific, they encountered a pre-existing vanguard of Native Americans who had settled the island. Perhaps it went the other way around, or perhaps exploring Polynesians reached the coast of South America and returned to the sea with Native Americans on board. Any of these possibilities is thrilling, and should swing our eyes around the globe to the unknown voyagers whose achievements surpass those of explorers whose names we know: Magellan, Drake, Vasco de Gama.

Shining over there

Is the morning star

Venus in the dawn,

Saturn in the night.

The world of light rises

Above a world left behind.

Although we do not know if Heyerdahl was right about who made the great journey, and in which direction, his theory that South Americans sailed west looks more plausible than ever. The part that he surely got wrong, as noted earlier, is the theory that Polynesia was first settled by South Americans, and that they belonged to a mysterious, pale tribe. Hīroa got closer to the truth on the settlement question than Heyerdahl in part because he listened better. He approached the myths of Polynesian culture with respect and patience, letting them lead the way. Not that such myths necessarily described history literally, but they revealed real and important pieces of evidence, which Hīroa put into dialogue with material evidence from the other sciences.

Ioannidis emphasizes that his approach was not merely a blunt application of genomic techniques on anonymous genomes. It was important to him to have anthropologists on the team who could help to ensure that research was not being done on indigenous communities, but with them. This anthropological approach is not only more ethically and humanly sound, it also improves the inquiries of the “hard sciences.” Years of work in anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, and other disciplines had set the stage such that the geneticists knew which questions to ask, where to look, and what to look for. Telling the historical and genetic story right “requires understanding the archaeological contexts,” Ioannidis told me. These are “important to motivate the questions we’re asking and to interpret the results.”

Beyond these methodological considerations, the motivation for the project had many other layers. On the one hand, Ioannidis speaks to his sheer wonder at the skill and prowess of Polynesian navigators and amazement at the mysterious history of the Pacific. But he had another, more personal motivation as well.

Ioannidis is the descendant of refugees. In the great forces that move history, his grandparents had been collateral damage. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the conflict between the Ottoman Empire and European powers, determined that Cappadocian Greeks, who had lived in their place for millennia, no longer belonged in Cappadocia, which was to be considered a part of modern Turkey. In his genetic research, Ioannidis hopes in some way to return to other displaced people pieces of their story that have been forgotten. He takes to heart these lines from the Cappadocian poet Rumi: “Tell me what happened to you, tell me what you have lost.”

This is the kind of story that interests Ioannidis.

Recorded history — it’s what the kings and queens were willing to pay a scribe to write down. And so we read about conquest and battles and who won…, but we don’t know what happened to the general population, to peasants and everybody else, basically. And some of those stories, like this story, are even more incredible than the recorded stories, and they are no less true just because they weren’t recorded. And it turns out they were recorded, it’s just they were recorded in our genomes.

There, in the genome, is a further motivation for the study. The larger context of this work is “to rectify disparities in genomic research among diverse groups,” he explains. Most genomic research has been done on white, European populations. Such a disparity demands redress, not least when it comes to studying the genetic markers for disease and understanding how these markers can help us track and treat illness in different ethnic communities. The markers vary across populations, and so tracing them becomes more complicated with populations such as those in South America, whose genomes are a mix between indigenous and European DNA.

The Polynesian–South American admixture provided a globally unique test case, because two genetically disparate populations met, mixed, and parted somewhere in the neighborhood of a thousand years ago. This distinct occurrence allowed researchers to develop new computational tracing tools, which can now be used in health research and clinical applications. Several of the scientists on this study apologized for being too busy to speak with me because they are hard at work on urgent Covid-related questions — such as identifying markers that indicate a greater risk of severe respiratory failure from the disease — using the very approaches they had developed on the Polynesian project.

The old net is laid aside;

A new net goes afishing.

Getting toward the truth about the world requires what the philosopher William Whewell termed “consilience,” that is, a “jumping together” of inductions from various fields converging on a single reality.

That single reality is always more abundant than we can anticipate, and the mysteries of the South Pacific show that finding it requires a scientific approach as fulsome as the world it studies: a world of particles and forces, and of story and song. It is a world in which the curiosity that drove Heyerdahl, the love for his people that motivated Hīroa, and the desire to serve that compels Ioannidis are as real as atoms and gravitational fields. A scientific outlook that ignores these things could tell us, in Erwin Schrödinger’s words, a great deal about the physical order, but would be “ghastly silent about all and sundry that is really near to our heart, that really matters to us. It cannot tell us a word about red and blue, bitter and sweet, physical pain and physical delight; it knows nothing of beautiful and ugly, good or bad, God and eternity.”

Scientifically and otherwise, there is something within the human soul that drives us ever on to the receding horizons, that tempts and taunts us with what lies across the waters, with what is not yet known. For some people, those horizons call like a siren, and they cannot be stopped from throwing their bodies among the smashing waves and the rocks in the hope of a further shore. On that shore lie not just formulas and abstractions, but red and blue, bitter and sweet, pain, delight, good and bad. Perhaps beyond the sea there is even something to learn about God and eternity. The only way to find out is to grab the paddle, meet the wave, and give chase to the sun.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?