Disinfect your door, wash your hands, stay at home. In the initial days of response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the mainstream advice focused on setting up and maintaining a private cordon sanitaire. Everything began from the presumption that home was safe and that individual citizens needed to find ways to maintain a clean perimeter. We started with the premise of a containable pandemic, a germ we could avoid with simple rules and sustainable precautions. In that world, infection indicated a moral failure to take basic precautions.

But that isn’t the pandemic we got, or the kind we should expect when the next pathogen comes burning out of an animal reservoir or a lab. Covid-19’s aerosolized spread, denied long past the point of plausibility by the WHO and other experts who knew better, is a double threat to our body politic. The disease has killed more than 750,000 Americans, and the wafting, hard-to-contain danger has exposed the flaws in our approach to public health.

We’re used to starting with a premise of safety and sterility. The goal of our policy and our private precautions is to return us to that baseline of nothingness.

The artist Anicka Yi uses scents as her medium, and, as she told the New York Times in an interview, she thought about how to replicate the crisp nothing that people expect as the marker of both safety and luxury. “I talk a lot about how power has no odor,” Yi explained. “This is why you should not be smelling any odors when you walk into a gallery in Chelsea, or when you walk into a bank. These are places of power and sterility.”

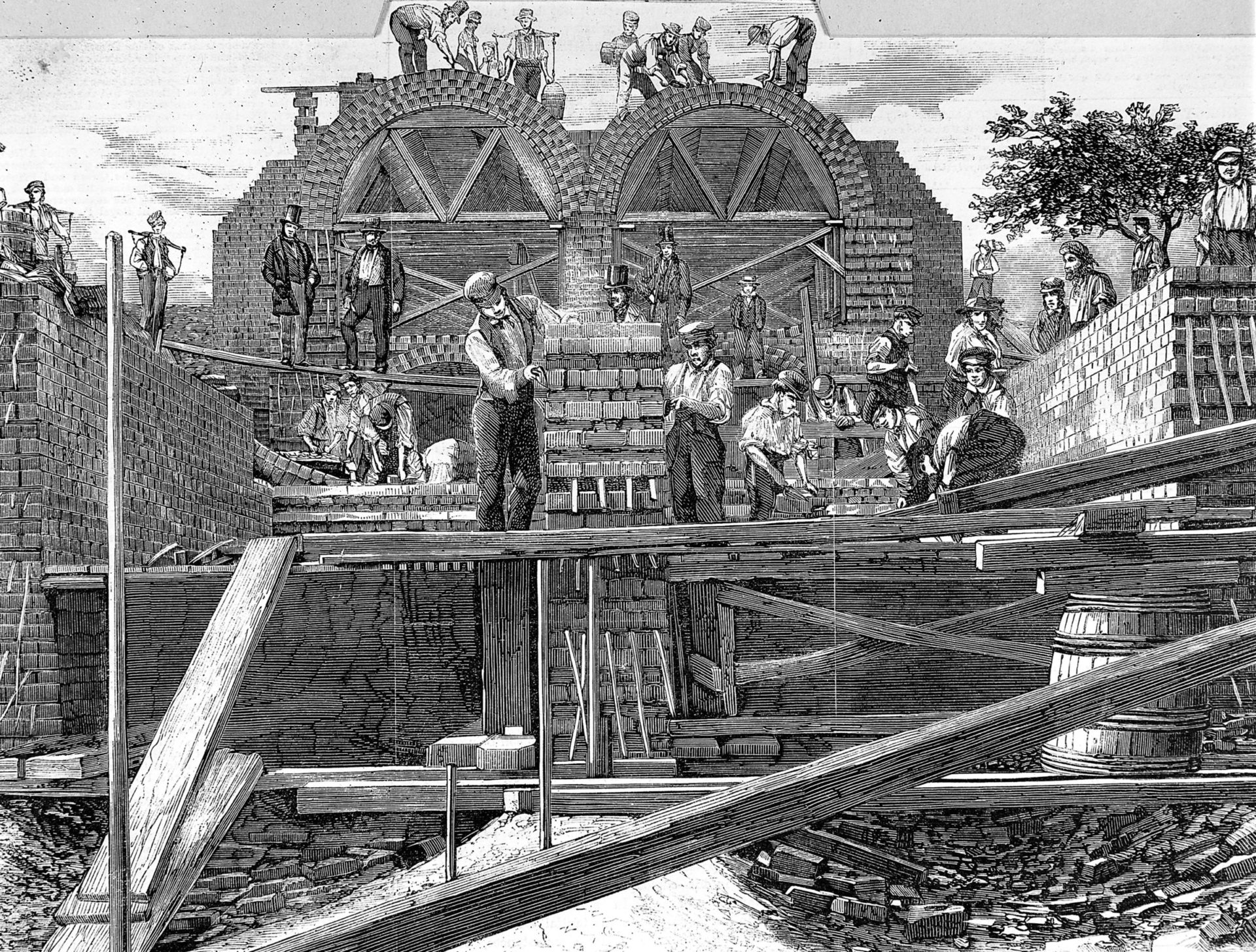

The alternative to safe sterility is a lively fecundity. Yi has made organic decay a part of her art, exhibiting an unrefrigerated tofu block under hot lights, and, most recently, attempting to replicate the scent of cholera-plagued London for visitors at the Tate Modern.

The Londoners who originally breathed the fetid stenches she attempts to recreate had a very different, and arguably more accurate understanding of disease than we do. Cholera was suspected of being carried by miasma (bad air), and staying safe meant figuring out how to diffuse, not necessarily eliminate, risk. Cholera itself turned out to be water-borne, but miasma theory hasn’t faded from relevance.

The distinction between disease as out there and as with us is one that Ross Douthat draws in The Deep Places, his new memoir of chronic Lyme disease. His illness pushes him out of the world of simple rules, established treatments, and effective containment, and back into an older understanding of the frailties of our bodies.

The old idea that people fell ill from bad airs and bodily humors made illness seem miasmic, omnipresent, inescapably part of what the body breathed and pumped and circulated. The germ theory of disease, on the other hand, allowed for a stricter separation between the body and external perils, with disease something entirely separate, a distinct life-form that, with enough buffering, could be excluded from the secure, protected flesh.

Lyme is meant to be contained by tick checks, CDC-vetted tests, and short courses of antibiotics. Douthat falls out of the established pattern of care at every step: no bullseye rash, just a sore spot that could be a boil; an ambiguous test result with not enough positive bands to count as “real” Lyme; and a protean ailment that lingers and shifts, burrowing through his body to take up new residences.

Instead of beating the bounds around a basically safe and healthy body, Douthat is left as an awkward gardener, trying to steward the ecosystem of his body, which may never be “cleared” again. It’s a challenge he sees as common to chronic illness, whether caused by Lyme or by Covid: “Chronic illness … suggests an inherent porousness and vulnerability, where something can get in unnoticed, evade tests and drug alike, and linger and spread for years.”

A public health regime that acknowledges the porousness of our bodies and our society faces a difficult balancing act. My right to swing my fist may end where your nose begins. But it’s hard to come up with the rule of thumb that limits my right to breathe when currents of air can dance my aerosolized virus past your nose.

In lieu of grappling with these questions, America has stuck to the idea that the responsibility for containment lies in individual virtue and precaution. At the same time, politicians have been reluctant to acknowledge the real conflicts between public health and civil liberties that come into play when we face an invisible enemy we can’t lock out.

The best solutions come from a miasma mindset. If we are willing to acknowledge our limited control of pathogens, we will focus less on lockdowns and masking-until-Covid-zero. Instead, the public health apparatus would focus on disease surveillance — welcoming homebrew tests at the outset of a novel disease, instead of banning them, as the CDC did.

The microCOVID project and Emily Oster’s Thanksgiving Safety Turducken both began from a miasmic mindset, even if they didn’t cite it by name. The microCOVID project quantified the risk of everyday activities, allowing users to think about spending a budget of risk on activities like going grocery shopping, inviting a friend over for dinner, and so forth. The project treated exposure in the way a radiation badge does — slowly darkening until you hit a risk threshold you consider unacceptable. Oster set out guidelines for holiday safety aimed at limiting risk, not eliminating it, by looking at each step of your plan (pre- or post-trip quarantining, masking, testing) and deciding how to combine various risk-lowering steps to push risk below an acceptable threshold.

There is no retreat to total safety, from Covid or anything else, but with better information, we can spend our risk budget wisely. Throughout the pandemic, the CDC has been reluctant to talk to Americans like adults, acknowledging that we have the power to reduce risk, rather than eliminate it. Instead, they treated citizens as one more system that could be controlled. Instead of sterilizing sprays, it was half-truths and exaggerations — public communication focused on engendering the right reflexive response rather than offering us the full truth.

We are all vulnerable, open systems. Our lungs are not, at least topologically speaking, interior organs. They are part of our surface — more like the nakedness of our faces than the tucked-away security of a liver. Our public health must start from the premise that we are present to the world, and total retreat is not an option. Then we will have the freedom and clarity to decide how best to face a lively, dangerous, and beautiful world.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?