Machine learning, advanced robotic weaponry, and many other “artificial intelligence” systems typically involve a human in the loop. The human is an operator who observes the computer’s ongoing processes and intervenes when necessary — think of a Predator drone pilot who watches live data feeds, interpreting and deciding when to pull the trigger. Taking the human out of the loop allows the user to “set it and forget it” — as with a lethal autonomous weapons system instructed to kill anyone who is armed within a given area.

ChatGPT, the generative AI chatbot which, it told me when I asked it, “can provide responses, answer questions, offer explanations, and engage in conversation on a wide array of topics,” functions impressively when there’s a human in the loop, guiding tasks and gaining information through a question-and-answer format. But what requires even more urgent ethical consideration is the development of what are named “AI agents,” such as AutoGPT and AgentGPT, that are being built to reduce the need for human guidance. These newer programs, which piggyback upon ChatGPT, have been called “the ultimate ‘set it and forget it’ for the AI era.” For example, as Clayton O’Dell has found, if you ask ChatGPT about a restaurant reservation, it will come back with a list of suggestions that compete with Google Search in their speed and accuracy. But if you give AutoGPT the same prompt, it not only finds a restaurant — it may use your email address to attempt to book a reservation. If ChatGPT is a new generation of Predator drone, then AutoGPT, AgentGPT, and related programs are fully autonomous weapons swarms.

Do programs that can make a dinner reservation for you today and plan and book an entire vacation for you tomorrow really deserve to be called agents? That seems like a yes-or-no question: Either the machine can plan and execute an action, or we’re just exaggerating when we call it an agent. Yet with many of our most important concepts, such as “goodness,” “health,” “beauty,” and “friendship,” we don’t simply say “yes it is” or “no it’s not.” Rather, these concepts have a range of application that is analogical. Such terms have a primary use, such as “healthy person,” and — by analogy to that — they have secondary uses, such as “healthy rainforest” and “healthy government.”

An AI agent lives up to its name analogically. It has more power to cause its own action than a chemical agent does, but less than a travel agent does. Its agency — its ability to select among alternatives on a decision-tree in pursuit of an end goal — is constrained both by its imperfections and its immateriality. But we say it is constrained because there is a greater, primary kind of agency outside it. An AI agent is a secondary agent, acting on its own but toward goals set by its user. It is the kind of agency that is familiar to anyone who has worked in a bureaucratic hierarchy.

AI’s capacity for agency is an urgent ethical matter because for every agent there is a patient. For every actor, there is a person or thing being acted upon. The fundamental question of politics, which deftly distinguishes ruler and ruled, is “Who, whom?,” as Trotsky paraphrased Lenin. C. S. Lewis (without quite meaning to) became an unlikely respondent to this question. In The Abolition of Man, he wrote that “what we call Man’s power over nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with nature as its instrument.” His answer works well for our context. On the individual level, technology often serves as an extension of the self. The automobile aids motion, while the cloud computer enhances memory. Yet on the social level, such technologies inevitably introduce new hierarchies and restraints. The small-town shopkeeper is run out of business by the highway bypass and the chain-store complex; reliance on Google’s products turns the user’s attention itself into a profitable product. AI opens whole new vistas for the latter kind of power-over-others, which has aptly been called “surveillance capitalism.”

An application programming interface, API for short, is a language that allows two programs to exchange information seamlessly. For example, your phone’s weather app uses APIs to download your local conditions from the National Weather Service. This is exceptionally useful. But as tech CEO Peter Reinhardt first made clear in a 2015 blog post, APIs can be used not only for one program to instruct another, but also for a program to instruct people. Workers “above the API” tell computers what to do; workers “below the API” are told by computers what to do. This is why one of the major categories of job growth forecast by economists like David Autor is “last-mile jobs,” such as bike messengers and underground cable locators, who accomplish the tasks that remain when the rest has been automated. Yet the assignment of these tasks itself is well in the process of being automated — think of the Uber driver who all day takes instructions from her phone, not merely about which passengers to pick up but also which route she must take, lest she be penalized for algorithmically-determined inefficiency.

AgentGPT and its clones can be expected to accelerate this process. There are about 50,000 Americans employed as travel agents; despite the ease of online booking, many people still prefer to pay for the service of a discerning human professional. But just as GPS reduces cab driving from a complex skill to a temp gig, so AI agents are poised to turn dozens, if not hundreds, of trades from comprehensive and demanding skill sets to the last-mile work of filling in the gaps.

So what? Aren’t language-based AIs threatening mainly white-collar jobs that workers themselves privately admit are of no social value — “bullshit jobs,” to use David Graeber’s famous phrase? In the book by that name, Graeber clarifies why, despite the prevalence of make-work in our economy, we feel such deep attachment to the other kind of work, the kind we deem fulfilling: because central to human experience, and even human identity, is “the pleasure of being the cause.” From infancy onward, we come to realize where we end and out there begins in large part through efficacious intentional action. That is, we do stuff and then see what happens. The sheer joy of having a plan, be it ever so simple, and seeing it come about is central to human life, and perhaps to Being Itself: as G. K. Chesterton put it, “A child kicks his legs rhythmically through excess, not absence, of life…. It is possible that God says every morning, ‘Do it again’ to the sun; and every evening, ‘Do it again’ to the moon…. The repetition in Nature may not be a mere recurrence; it may be a theatrical encore.”

AI may not deplete humanity’s total stock of agency, but it could well redistribute it in an all-too-familiar fashion: Whoever has, will be given more; and whoever does not have, even that little shall be taken away. And life without agency is not merely joyless, it is an impoverished life. Prisoners in solitary confinement have been found to suffer physiologically as well as psychologically, and indeed, a basic cause of suicide is the belief that one is powerless to change one’s circumstances.

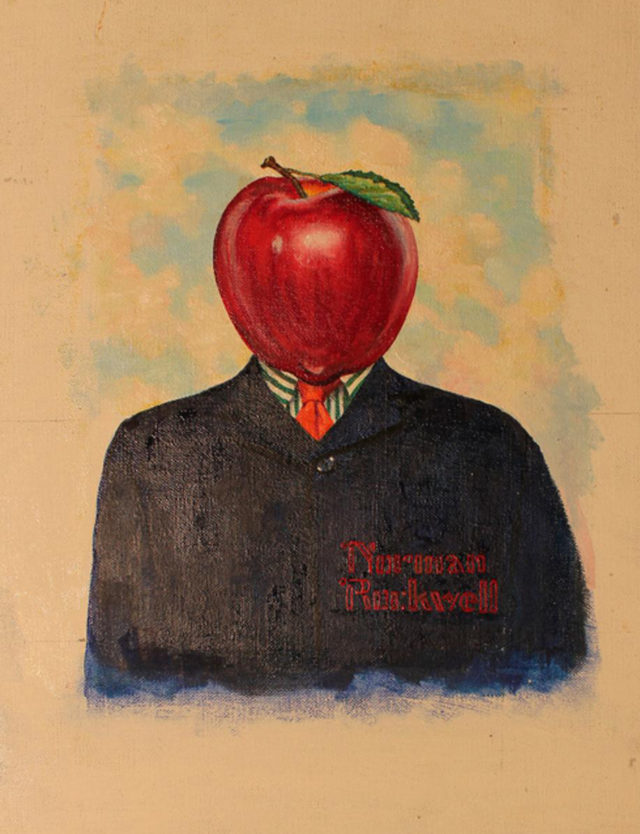

On the flip side, there is a joy or at least a justice in having what acts on us be an embodied agent. Much of the alienation we already experience in modern life comes from being pushed around without even the consolation of knowing that someone is doing the pushing. To put it in terms that corporations might understand: If the possibility of workers losing their purpose isn’t worrisome, the possibility of customers losing their minds should be. Even in a Kafkaesque encounter with bureaucracy, there is always a slim hope of appealing to the human being who still remains hidden within the job description, behind the desk. But when AI agents become capable of replacing white-collar jobs and acting with agency in social roles, that distinction between person and role is elided, and we go from René Magritte’s famous portrait The Son of Man, depicting the archetypal functionary as an anonymous man in a suit, face obscured by a floating apple, to the world of Norman Rockwell’s satirical Mr. Apple, which takes the same suited man but altogether replaces his head in favor of the fruit. We become confronted with a humanoid whose “face” itself is the API directions, the chat-box prompt, the disembodied AI voice in one’s ear.

Yes, technological agents that we control might serve to become great extensions of the mind, in much the way that a kayak or an airplane becomes almost another limb to an expert operator. But gains at the individual level may not make up for losses of social freedom and responsibility. It will not be nearly good enough for a handful of humans to run the machines and the rest to have self-appointed ethicists asking for coding transparency and feedback mechanisms.

If we want to retain any semblance of self-governance, we will need to find means for subsidiary, localized, even personal ownership and management of these AI agents. Otherwise, the triumph of postmodernity will entail a return to premodern hierarchies of social organization, where only a small minority has sufficient access, ownership, and status to exercise their agency and attain the full range of human excellence. The creation of perfect AI servants, if embedded in social structures with roles designed to maximize profit or sustain oligarchy, may bring about not a broad social empowerment but a “servile state,” formalizing the subjugation of an underclass to those who control the means of production — or of perception, to borrow from James Poulos. To answer “Who, whom?,” we need only discover who designs the virtual- and augmented-reality headsets, and who wears them; who instructs the AI agents, and who is impacted by their actions.

Perhaps all this is overblown. Perhaps, indeed, we secretly long for complete surrender to “the utopia of rules,” as Graeber argues in another catchily-named book. Perhaps our fantasy entertainment is as rife with swords and spells as it is in order to reassure us that life in kinship-based societies under charismatic leadership, where each member has a life-or-death contribution to make to the tribe, is romantic but ultimately too risky, too dangerous — too demanding of our agency. Perhaps we are all too willing to trade in the joy of being the cause of something for the comfort of being without responsibility. Perhaps our most besetting vice is not pride or greed but acedia, sloth, which shies away from the good because it challenges us to grow.

Perhaps we should welcome our new robot overlords — the efficient agents of our present ruling class.

More from the Summer 2023 symposium

“They’re Here… The AI Moment Has Arrived”

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?