This essay is accompanied by the New Atlantis critical edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “The New Adam and Eve.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The New Adam and Eve” (1843) is an account of two just-created innocents wandering through Boston and its environs the day after the entire human race has disappeared, instantly and entirely. This “half sportive and half thoughtful” effort to untangle the role of artifice and nature in shaping human life presents the unwary reader (if there are any unwary readers of Hawthorne) with a temptingly simple lesson that is almost certainly not the author’s last word on the subject. Nature is “bountiful and wholesome,” while art is a “crafty” (what else?) stepmother. We might readily associate art, then, with the “perverted mind and heart of man” and the “iron fetters” that chain us to “the world’s artificial system.”

But even in the story’s first paragraph there are complications that suggest the extreme teaching may be more sportive than thoughtful. Those “iron fetters” are not art, but that “which we call truth and reality,” and they are to be opposed not by nature but by imagination. (On this point Hawthorne sounds more like Plato’s allegory of the cave, inviting us to conceive of that which is not in front of us, than Rousseau’s First Discourse, lamenting the corrupting influence of civilization and science.) There is also a question with respect to the “perverted mind and heart of man.” Is Hawthorne suggesting that they have been perverted by art, or that art is an expression of this perversion — and if the latter, is it possible that the mind and heart are perverted by nature? And can we be confident that the imagination, which is supposed to liberate us by showing us our world through innocent eyes, is not itself compromised by a perverted mind and heart?

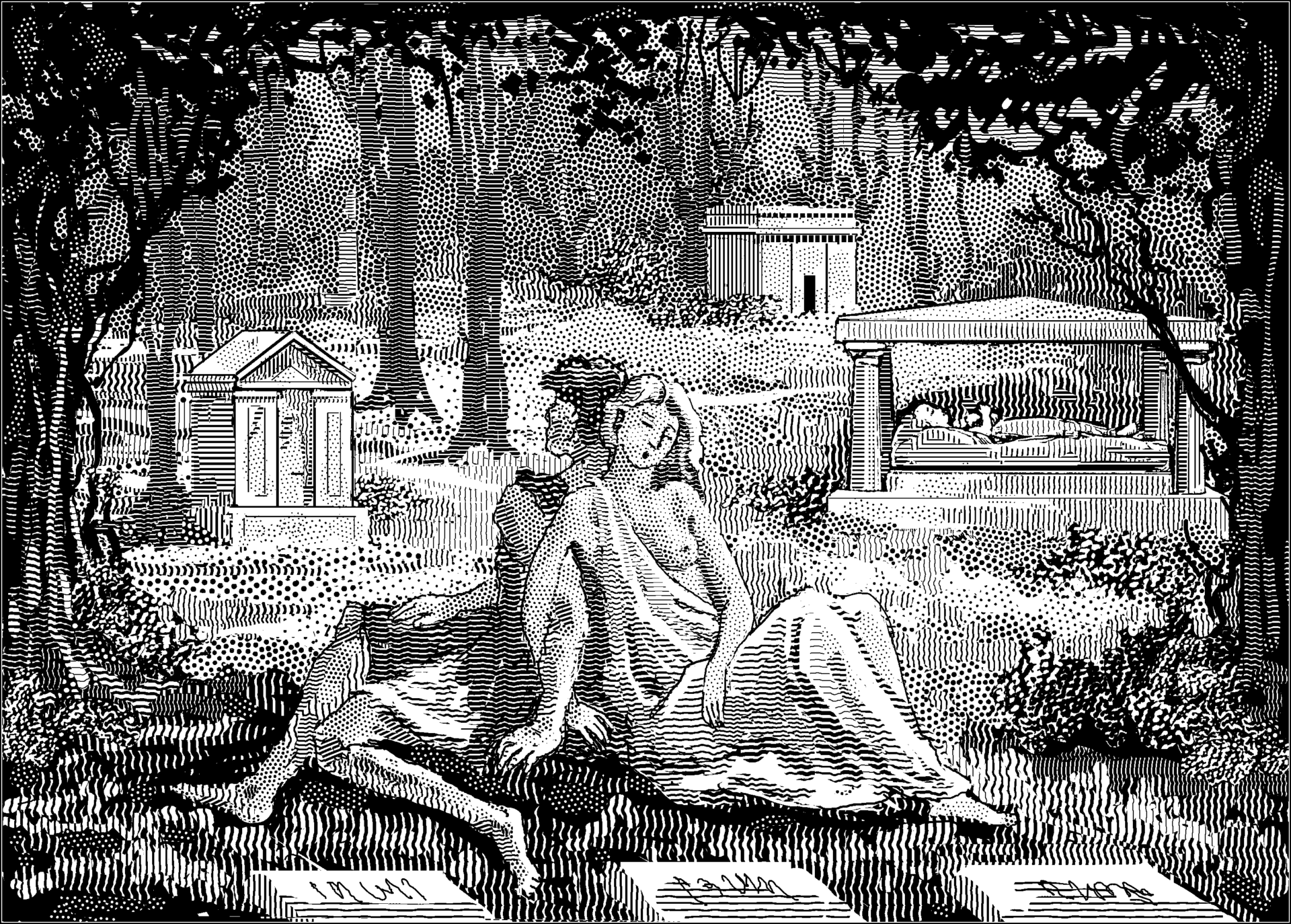

Our narrator asks that we imagine the new Adam and Eve “in the full development of mind and heart,” thus tempting us to believe that the full development of mind and heart not only does not require but may be impeded by art. For we are thrown into our “artificial system” and therefore cannot readily distinguish between nature and art. Yet the new Adam and Eve, thrown into the same artificial system, are touchstones for distinguishing art and nature. How can that be? They are certainly not Rousseau’s solitary proto- or savage humans; indeed, they come equipped with speech “or some equivalent mode of expression.” Only in their very first moments do they stand silent in “calm and mutual enjoyment” of the simple fact of their being together.

But soon they feel “the invincible necessity of this earthly life,” and they turn into diligent explorers, covering between six and ten miles in their day-long tour of the Boston area. (Today’s Freedom Trail around Boston, which exhausts many a tourist family, is two and a half miles.) They enter a dry goods store and then a church, followed by a courthouse, legislative house, and prison. They then enter a “hospitable” Boston mansion — “one of the stateliest in Beacon Street” — and curiously investigate the artifactual remnants of domestic life. They next proceed down State Street, the site of the old State House and a business exchange (now known as Faneuil Hall), before entering a bank and then a jeweler’s shop. At some point they cross the Charles River, visiting the monument commemorating the Battle of Bunker Hill before walking along the river toward Harvard. After exploring the university’s library, they reach the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, where their day of touring ends.

The new Adam and Eve may lack nouns for much of what they see, but from early on they can speak conceptually: of their “odd situation” and of their proto-philosophical need to “gain some insight” — all men desiring by nature to know — and later to inquire after their purpose, their “business in the world.” Yet for all that, they are only able to detect glimmerings of what around them might have been created by beings like themselves, and there is no corresponding sense that they have discovered “nature” as such. The new Adam and Eve are touchstones for us only; it takes a civilized mind and heart to comprehend the lessons they teach.

Untangling Hawthorne’s effort to untangle the role of art and nature in “our present state” requires a closer look at two aspects of “The New Adam and Eve.” Adam and Eve visit a dozen sites in the Boston area. Five of them are more or less incomprehensible to them and seven are more or less comprehensible. A close look at this schema will serve to clarify what Hawthorne thinks about the role of art and nature in shaping human life.

We begin with the incomprehensible sites. Of their visit to the Court of Justice our narrator says, “what remotest conception can they attain of the purposes of such an edifice?” Their visit to the Hall of Legislature is just “as fruitless an errand.” While a visit to a prison disturbs them and the sight of a gallows fills them with “nameless horror,” our narrator makes clear that they can have no understanding of the purpose of the building or the foreboding frame. He does not even attempt to characterize their reaction as they walk down State Street past the old State House and Exchange, as none of the activity that made this place what it was is even evident when all its former occupants are gone. At the Bunker Hill memorial, the new Adam and Eve misinterpret the obelisk, giving it a “purer sentiment” than its builders intended, for they do not yet know that one generation of men could create the carnage of a battle and the next commemorate it.

Faneuil Hall, one day earlier a bustling business exchange, provides a clue to understanding what it is that the new Adam and Eve cannot understand. In this, as in all the incomprehensible cases, the activity that goes on at the site is not essentially indicated by the nature of the building in which the activity takes place or by its contents, nor is the building even essential to the activity. Hawthorne makes this point explicitly in connection with the Hall of Legislature when he reminds us of our pilgrim fathers’ “little assemblages of patriarchs” who met not indoors but “beneath the shadowy trees.” The look of the prison might seem more obviously suggestive of its former purpose, but of course people can be confined, punished, and executed in a host of ways that do not require something that looks like a jail and gallows. Likewise, the memorial at Bunker Hill (actually situated on Breed’s Hill) gives no clue as to what is being memorialized; the pair interpret the obelisk only as “a visible prayer,” pointing as it does toward the sky that they recognize as the heaven to which they long to ascend throughout the story.

What makes this disconnect between site and activity possible is that legislation, judgment, punishment, and conflict — in short, the whole realm of politics and convention — is more rather than less a product of the mind. The same might be said of the realm of contract and commerce of the sort that went on at the business exchange. We should not be surprised that the new Adam and Eve do not understand the great artifice (or so our narrator believes it to be) of civil society. Whether or not civil society is blameworthy simply for the fact of its being an artifice — whether it corrupts natural human purity — is a question we will take up shortly.

The criticisms that the narrator makes of the realm of convention are unsurprising: judgment and punishment lack love and businessmen are worldly. Perhaps the boldest claim is that, were the world’s legislation to be a combination of “Man’s intellect, moderated by Woman’s tenderness and moral sense,” there would be no need for legislatures. Putting aside the inherent problem of legislation without legislatures, this solution to the world’s problems calls our attention to the importance of properly combining masculine and feminine virtues. As it happens, this topic is thematic in the discussion of a number of the sites where Adam and Eve have some comprehension of the activities of the lost world.

When the new Adam and Eve visit a dry goods store, a church, a private home, a bank, the Harvard University library, a jeweler’s shop, and the Mount Auburn Cemetery, they respond in some fashion appropriately to what they find there. At the dry goods store, Adam suffers “a fit of impatience” in response to Eve’s attention to the fabrics, but is very pleased when she drapes herself fetchingly, and likewise drapes himself. Gems and gold coins are objects of delight for them as for us, but following the narrator’s observations about “huge packages of banknotes,” Adam also wonders whether all that carefully collected “rubbish” somehow relates to the work he and Eve should be doing in the world. At the park-like Mount Auburn Cemetery they enjoy the mix of nature and art, and yet also are close to an appreciation of the possibility of their own mortality mixed with confidence in God’s loving care for them. The aspiration towards heaven that they have felt from the very beginning of their sojourn on earth they feel in a modest way inside the church. Indeed, in this case it could be said that the American “metropolitan church” they visit is insufficiently a product of human art, since our narrator believes the European cathedral conveys much more clearly its spiritual message.

The narrator’s own opinion of that message is obscured. The new Adam and Eve never encounter a realistic crucifix, although if they shudder at a bare gibbet one can hardly imagine them being anything but horrified by it. Of all the forms for commemoration of the dead that are mentioned in connection with Mount Auburn Cemetery — “marble pillars, mimic temples, urns, obelisks, and sarcophagi” — it is a cross that is most obviously missing. How Hawthorne sees the spiritual inclination of the new Adam and Eve to ascend to heaven in relationship to the institutions of revealed religion is a complicated question. As we encounter them, they are apparently not yet what the orthodox would call fallen. “Hasten forth” from the prison, the narrator urges, lest the plague of sin infect you and “thus another fallen race be propagated.” Eve bites an apple in the mansion; the narrator expects this act will have “no disastrous consequences to her future progeny.” They come closest to eating “the fatal apple of another Tree of Knowledge” in the library; we will return in a moment to the distinctive meaning of that narrow escape.

In the private mansion they begin to understand that what amazes them might be a product of beings like themselves. Seeing themselves in a mirror begins the necessary train of reflection (so to speak). That experience is further built upon by coming across the sculpture of a child, which they understand in a way that they could not understand the portraits of bedecked men and women they saw on the walls. While Adam’s first thought is to wonder where the former residents of the world have gone and why their world is “so unfit for our dwelling place,” Eve seems much more at ease with the trappings of domestic life: she slips a thimble on her finger, handles needlework and a broom, and taps out a tune on the piano. Only at Adam’s instigation do they leave to begin the longest part of the journey.

Of course, in all these cases our narrator continues to make his sportive critical comments on “our present state”: Who would think of turtle soup as food? Unlike us, Adam and Eve enter the church not merely to show off their new clothes! Money is just paper! But surely we are entitled to notice the actions of the characters as well as the narrator’s comments, and to give those actions weight. For there is much artifice the new Adam and Eve encounter that is attractive to them even in their natural simplicity, and much in civilization that speaks to their deepest inclinations, both material and spiritual. We see a broad arc to the journey of the new Adam and Eve if we step back from it with the thought that art and nature are not simply opposed. Thus, at the first site they visit, the dry goods store, the new Adam and Eve expose the complicity of art and human nature when they adorn themselves not out of modesty but out of delight in their appearance to each other. No snake and no apple are required for the new Adam and Eve to cover themselves. As noted above, Hawthorne only emphasizes the difference between his story and the biblical version when, at the midpoint of their journey, the mansion, it is the new Adam who offers the new Eve an apple that she eats with no dire consequences, the apple being immediately recognizable to them as natural food. The deep interpenetration of nature and artifice in the household — a building, indeed, where the most natural of needs is met through art: the need for shelter — makes it hard to distinguish which we are seeing, and yet after the new Adam and Eve’s moment of reflection it also intimates their commonality with those whose domain they are exploring.

The last site visited, Mount Auburn Cemetery, emphasizes in its own way the high possibilities of the cooperation of art and nature. If Hawthorne had wanted to close merely with a memento mori — and plainly that is part of his intention — he could have chosen any of the many cemeteries around Boston. But he chose not an old churchyard with its worn tablets but a burial ground of a then-new design, a cross between a large public garden-park and a cemetery. Here nature and artifice cooperate, the “fantasies of human growth” promoted by the effort to commemorate the dead with “the flowers wherewith Nature converts decay to loveliness.” In both cases, without corruption there would be no beauty.

Hawthorne seems to be suggesting that our present system is not some alien artifice imposed on our nature in an arbitrary or chance fashion — as Rousseau would have it, this time in his Second Discourse — but an outgrowth of the fact that we are artful beings by nature. We might understand human art broadly in the same terms the narrator uses to describe the Æolian harp “through which Nature pours the harmony that lies concealed in her every breath, whether of summer breeze or tempest.” The harmony of nature is concealed until revealed by human artifice, just as the draped new Eve is somehow more charming to the new Adam.

If we notice that the arts arise out of our nature, we are more likely to observe also that not all is necessarily harmonious within that nature. Where Adam during their visit to the mansion comes to wonder “why we have been sent” into the world and whether “there is labor to be done,” Eve is content that they simply love each other, and that nothing come between them. Eve is brought to “mute reflection,” though, by the items in a baby nursery; for Adam they are merely trifles. Likewise at the Harvard library, Adam is certain the books are trying to tell him something important, while Eve is impatient to depart. At the bank, Adam considers whether the carefully stacked money might be a clue to their own purpose, their “business in the world”; meanwhile, Eve insists that “it would be better to sit down quietly and look upward to the sky.” We begin to see why the integration of masculine intelligence with feminine tenderness and moral sense that would obviate the need for legislatures is not to be taken for granted. The new Adam and Eve share many traits but they do not see the world in the same way. The possibility of their domestic harmony will depend on something coming between them, some work that must be done that will support that harmony and yet at the same time will compromise it.

And will not such tensions already evident in their little world become all the more marked as out of the new Adam and Eve springs a new race of men? For, unless these men are to live like so many Robinson Crusoes, will not their natural desires for pretty things, for work to do, for domestic security, for reaching into the sky, bring them together in ways out of which naturally will arise exchange, and out of which naturally will arise conflict, and the need for punishment and politics and convention? In this sense, then, the great artifice of civil society arises out of our nature. And with it will arise the very possibility of war and oppression which our narrator claims makes the Bunker Hill memorial so incomprehensible to the new Adam and Eve. If by nature we love our own in the manner the new Eve repeatedly suggests by her wish never to be parted from the new Adam, and if by nature we will protect our own, as her own maternal feelings suggest, then we can see the potentially fierce and fearsome consequences that can follow from masculine intelligence combined with feminine tenderness and moral sense.

Hawthorne’s story shows us that for better and worse the “mind and heart of man” are not perverted by artifice, but that they are found in artifice — that human beings are artistic not in opposition to nature, but by nature. Hence, when our narrator commends the new Adam for casting aside the books in Harvard’s library and thereby avoiding inundation by all the errors of our own humanity, it is not in the expectation that the new race of men will succeed where the first failed because they will avoid the chains of artifice. As they go to sleep in Mount Auburn Cemetery, the new Adam and Eve do not seem poised to flee far from the things of man on their heavenward path. But Hawthorne just as clearly does not wish them to expedite their progress by feverish efforts to recover the lost legacy of the first race of men. While the complicity of nature and art in making us what we are allows us to imagine perfection based on one or the other, Hawthorne seems content if the new Adam and Eve achieve possibilities inherent in their combination that are not entirely alien to any of us: to make their own mistakes, to create their own art, even to collect their own rubbish.