At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, hospital administrators behaved as cautiously as possible to avoid transmission and dissemination of the virus. They strictly limited or eliminated hospital visitors. This was one of the most devastating policies enacted by healthcare institutions. As a consequence, not only were patients left without family at their bedside to advocate for them, but they were, alas, left without family at bedside to say goodbye to them as they passed. Families needed to FaceTime their loved ones near the end; no hands were held, no one gathered around the bedside. At their most vulnerable moments, patients were deserted.

Writing in The Atlantic last summer, Zeynep Tufekci described the tragic situation these policies created:

Of all the wrongdoings of this pandemic, the one that haunts me most is how people are left to die alone. Health-care workers have been heroic throughout all this, but they do not replace the loved ones whom the dying need to be with, and speak with, even if only one last time.

As we faced the second-wave of the coronavirus over the fall and winter, with overburdened physicians and nurses, overcrowded wards, and a dramatic increase in Covid-19 cases, hospitals once again cut down on family visitation. This time, thankfully, many institutions have been relaxing their policies. The University of Pennsylvania, Temple Health, MedStar, and Geisinger are some healthcare systems making rare exceptions to their no-visitation injunctions. They now allow visitation for patients the ends of their lives. This is an important start. But with cases declining rapidly, we need to be even more liberal about visitation policies now.

A few years ago I accompanied a family member to a doctor’s appointment. After a traumatic scrape she had gotten a superficial skin infection and required a brief course of antibiotics to treat the infection. It would be a quick and easy visit. A culture had been taken from the traumatized skin prior to the visit to determine if there was a particular bacteria that could be treated. This helps the physician prescribe the right antibiotic, one that will actually kill the bacteria or stop its growth. The doctor showed us the results of the culture and told us what she was going to prescribe. As I looked over the culture report, I noticed the bacteria was, in fact, not sensitive to the antibiotic she prescribed and pointed this out. Admitting her error, the doctor switched the prescription.

Interactions like this happen in doctor’s offices and hospitals throughout the country because physicians are humans and make mistakes. Family members at the patient’s bedside or in the clinic with the patient help catch those mistakes to improve patient care. Furthermore, if a patient isn’t feeling well or doesn’t look well, physicians who don’t know the patient might miss subtle changes in the patient’s appearance but family will point them out.

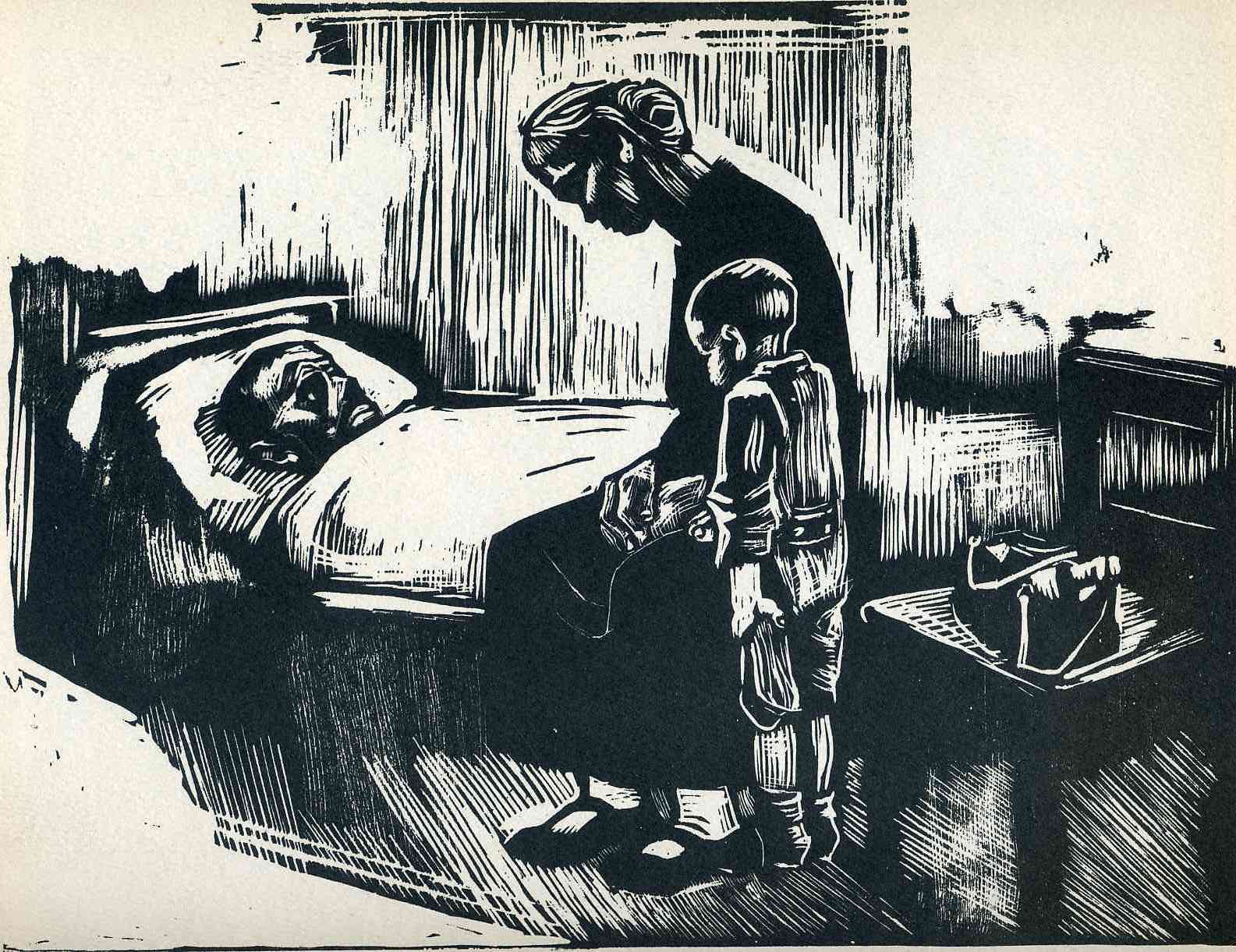

Käthe Kollwitz

Research bears at least some of these positive effects out. In one study published in 2013, the burn intensive-care unit incorporated families in dressing changes (burn patients require frequent changes of the dressings over their burns). They found that patient satisfaction scores increased and infection rates did not increase. In another study from 2017, a meta-analysis, integrating caregivers into discharge planning at the conclusion of hospitalization actually reduced the risk of hospital readmission. Another study found that among those stroke patients admitted to the hospital, family members and their accompanying positive attitudes improved cognitive outcomes in post-stroke rehabilitation. While there can certainly be downsides to having families intimately involved in medicine, such as stubborn requests for certain dangerous medications or interventions, families are a boon to their loved ones.

Why, then, are we so aggressive about limiting visitors? There is a reasonable concern that visitors could bring Covid-19 into the hospital if they’re asymptomatic. They can get their admitted relatives sick. They can get healthcare workers sick. Perhaps it could cause a super-spreader event in the hospital. While these concerns are certainly valid, patients lose the benefit of having their loved ones at bedside. Some of my friends have had to watch from afar as an immediate family member disappears into the bowels of the intensive care unit for weeks, sedated, paralyzed, and intubated, their only line of communication through overworked and exhausted nurses and resident physicians.

While we ought to be cautious, we don’t need to be as strict as we currently are. The risk of Covid-19 transmission in hospitals is incredibly low, as this JAMA article indicates: Of 697 hospitalized patients with Covid-19 only one was infected after exposure to the virus in the hospital. Though, admittedly, this case was from a pre-symptomatic spouse who was visiting daily, it occurred at a time before visitor restrictions and masking were implemented. In another hospital, of 44 healthcare workers exposed to a patient before contact and droplet precautions were implemented, 2 of the 44 (5%) developed Covid-19 “potentially attributable to the exposure.” So while the risk of infection with Covid-19 certainly exists in hospitals, aggressive masking and handwashing can mitigate that risk. Moreover, certain units are more protected than others. This British Medical Journal editorial points out that “Working in intensive care units is not associated with an increased risk of infection, possibly owing to the protection afforded by high level PPE or to the decrease in infectivity that occurs in the later stages of the illness, even among critically ill patients.” They continue: “The greatest risk to healthcare workers may be their own colleagues or patients in the early stages of unsuspected infections when viral loads are high.”

Given the benefits of family visits, and the relatively low risks of infection in hospitals, one needn’t advocate for opening the floodgates to all visitors, but more exceptions should be permitted. For instance, we can allow a limited number of family members (one or two) into units where they are needed most and at the lowest risk of transmitting infections, like the ICU. This would be helpful for the patients. An aggressive rapid testing policy for family members of patients coming to visit would further mitigate any risks. These would need to be done on a limited basis for the families of sicker patients. Visiting hours can be limited. And, of course, a universal masking policy and frequent handwashing policy should absolutely be in place. Hospitals can be strategic, cautious, and generous in a targeted fashion, ensuring that more patients safely have advocates and loved ones at their bedsides during the pandemic. It will make this devastating pandemic a bit less devastating.