There are certain patients who never fade from a doctor’s memory — they make an indelible imprint on one’s training. Thinking back on these patients and their respective hospitalizations is like gazing through a pristine window pane on a clear, sunny day. Often they stick in our memories because one becomes emotionally invested in them or because there is some interesting disease or singular clinical outcome. The former patients usually affect us more deeply.

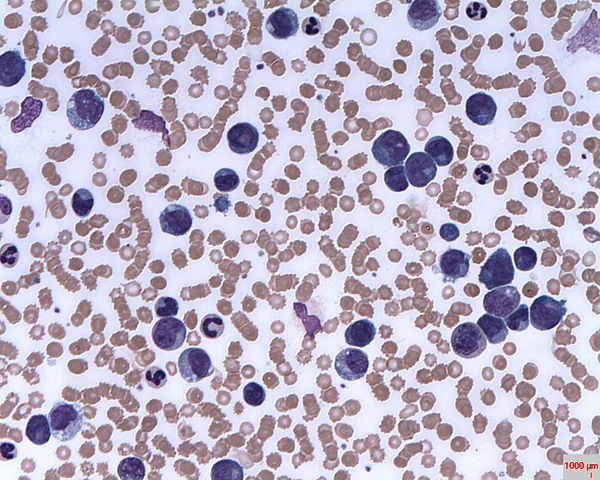

Prof. Erhabor Osaro via Wikimedia

I can tell you her name, age, and favorite foods to eat and cook. I recall, without difficulty, how many children she had, her religion, where she grew up, traveled and met her husband. I can even recreate her hospital room in my mind — family pictures across from her bed, a knitting kit on her nightstand next to her laptop computer, a plastic storage bin with clothing and candy.

She was in her fifties and had been diagnosed with leukemia, a cancer of the blood. There are different types of leukemia, but in general, patients with leukemia have bone marrow that overproduces certain infection-fighting cells, or white blood cells. Some of these cells function normally, but many do not. They overcrowd the marrow, preventing it from making red blood cells and platelets. If there is a high enough number of them, they clog up blood vessels. And eventually, the cancer kills you.

Treatment of leukemia involves rounds of chemotherapy, potent drugs that arrest cell growth or division by acting on a specific stage in a cell’s reproductive cycle. Each of these drugs targets different aspects of quickly dividing cancer cells. But they also wreak havoc on the body’s normal cells, causing nausea and vomiting, hair loss, heart damage, kidney damage, and liver damage. Unavoidably, the therapies for leukemia have serious, sometimes intolerable side effects.

The goal of prescribing such potent medications is to wipe out all of the cancer cells. But it is especially important to wipe out the “stem cancer cell” — that is, the original cell or group of cells causing this tempest. If you can’t kill those cells, you cannot cure the cancer; they divide and produce more defective, parasitic, and deadly neoplasms. For certain patients a bone marrow transplant is the best hope for a cure. Chemotherapy wipes out one’s own bone marrow and cancer cells to make room for the transplant, which does not contain the same cancer progenitors. The donor’s marrow must match the patient’s marrow; the cells produced from the transplant must be sufficiently genetically similar to the patient’s or the white blood cells from the donor tissue will attack the patient’s own body.

Our patient had gone through multiple rounds of chemotherapy, all of which failed. She had found a match for a bone marrow transplant, though, and was going to try a new combination of chemotherapeutic drugs to wipe out her bone marrow in preparation for the procedure. This process takes weeks. Thus, she lived in the hospital, receiving family along with friends from church. During the afternoons, after rounds, I would come by and chat with her if she wasn’t too exhausted or sick. Our conversations wandered from religion to food, travel, and family. We talked about history, too. She was a Civil War buff and had no trouble discussing her favorite historical figures from that era and her favorite speeches.

She possessed a seemingly infinite amount of patience and kindness given the circumstances. I never once heard her bemoan her situation. She wanted, I think, to be treated as she had always been treated, even as the reality of her prognosis set in. If she hadn’t had children, she once mused to me, she would have given up after the last round of chemotherapy failed and opted for palliative care. But her children were too young to lose their mother, and so she hoped to live on. So we hoped with her, attempting just once more to extend her life.

At a certain point towards the end of the chemotherapy regimen, we extract bone marrow from the patient and look at the marrow under the microscope with a pathologist. A hematologist aspirates the sample using a large needle and spreads it onto an approximately three-inch-by-one-inch slide. The oncologist, pathologist, residents, and students look at the small sample of tissue. Ideally, there are very few cells and almost no cancer cells. Otherwise, the chemotherapy has failed and the transplant cannot be done. As the pathologist moved the slide of our patient’s marrow around, large dysmorphic cells popped into view. There weren’t a lot of them, but they were noticeable and they were cancerous. I heard the pathologist offer up a disappointing, “Hmmm.” No, as it turns out, the chemotherapy had not killed enough cancer cells to make the bone marrow transplant worthwhile. Tragically, the patient would soon die.

It is strange, is it not, that this human being’s outcome depended on an inch-wide sample of bone marrow? We do not think of people as bundles of organs and cells but as whole, complete beings. We think of people abstractly or even holistically — character or personality, physical and mental abilities, age. Who cares about the cells in their marrow? What bearing does that have on the life to be lived? But it matters much more than it seems. This small sample ends a life or gives fresh winds to a sick life. It is counterintuitive to the way we think, but it is how we make decisions in medicine. We treat the person but we also treat the disease. If the disease still exists and runs rampant within the body, the person, no matter how admirable, familiar, and recognizable, will perish.