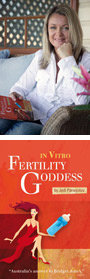

This month’s Conceptions interview subject is Aussie Jodi Panayotov, author of a new infertility memoir, In Vitro Fertility Goddess. (For the first interview, click here.) At age 37, Jodi was dismayed to find that her fertility had “packed up and left home without a forwarding address.” Never one to give up easily, she and her husband, Michel, enlisted a “medical Coalition of the Willing” to help them have a baby. After a two-and-a-half year journey, they had a daughter, Nina, now five years old.

This month’s Conceptions interview subject is Aussie Jodi Panayotov, author of a new infertility memoir, In Vitro Fertility Goddess. (For the first interview, click here.) At age 37, Jodi was dismayed to find that her fertility had “packed up and left home without a forwarding address.” Never one to give up easily, she and her husband, Michel, enlisted a “medical Coalition of the Willing” to help them have a baby. After a two-and-a-half year journey, they had a daughter, Nina, now five years old.

Jodi has been called “Australia’s answer to Bridget Jones,” and her book is an irreverent, edgier take on the new Repro-Lit genre. In the interview, we discuss why IVF is “the new black,” whether women really can “have it all,” and how to talk to your friends and family about infertility.

Jodi also blogs up a storm at her website—take a look! The book is on sale here.

[Interview edited, condensed, and hyperlinked by Cheryl Miller. Part two to follow.]

There has been an explosion of infertility memoirs recently: Peggy Orenstein’s Waiting for Daisy, Beth Kohl’s Embryo Culture, Tertia Albertyn’s So Close, etc. One critic has even given the genre a name: Repro-Lit. Why do you think accounts for the sudden interest in infertility?

JP: Years ago there was almost nothing written about it that wasn’t so dry you needed several jugs of water handy while you read it.

I think the surge is a result of a couple of things—firstly, a pent-up demand from women who have felt terribly isolated in their experience of infertility. As I say in my book, women will so readily talk, ad nauseam, about their reproductive successes but not their reproductive failures.

And of course as more women are postponing childbearing for various reasons, every day there are more of us in stirrups being prodded at the specialist’s office going, “What happened? How the hell did I end up here?” Hence there is more demand for books on this topic.

What is an “in vitro fertility goddess?”

JP: A fertility goddess is the woman who reproduces readily and with ease. I used to find them so annoying. Then the only way I got to join them was with the help of “in vitro.” Hence “In Vitro Fertility Goddess.”

What prompted you to write the book? Who did you imagine as your intended audience?

JP: I didn’t write it with an intended audience in mind. It was based on a diary I was keeping as a sanity clause during the infertile years—the miscarriages, the drugs, the herbs, my mother’s sex tips, IVF, and the troubled pregnancy spent mostly in bed. When I looked back on it I thought there’d be stuff there that many sufferers of infertility would relate to and from feedback I’ve received they have.

However I have found that the response from the ‘fertiles’ who’ve read it has been unexpected and amazing. They’ve said it’s given an insight in an easy-to-read way on what friends and family have gone through and really changed their ideas on what it means to struggle to have a child. And it’s made plenty of them feel more privileged to have had their children easily. And, dare I say, even appreciate their children more.

In the book, you write about the homicidal thoughts you had about pregnant women, your obsession with your basal temperature and bodily signs, your frustration—even anger—with “fertiles.” Were you ever nervous about laying yourself bare like that?

JP: I think when you are writing autobiographically it has to be a risk you are prepared to take if you are being honest about your subject. Otherwise you can disguise it and turn it into fiction but I don’t think it has the same impact or resonance with the reader.

How have people responded to the book? Have any family or friends read it?

JP: My father made sure that all the family read it. Nobody was spared, including a seventy-eight year old uncle and ninety-year old great aunt. Which goes to show that there’s something in it for everyone—you’re never too old to read my book.

Interestingly enough the friends who have been closest to me during the years of struggle to conceive have reacted with utter surprise to see what it was really like for me. They’ve said they had no idea and why didn’t I talk to them? To which I’ve said, “Well it’s a bit hard when somebody calls and asks what you’re up to, to say, ‘Oh I just spent two hours with my hand in my vagina checking my mucus. How about you?’” Of course, now they all know that’s what I was doing and dinner parties have never been the same.

Do you think your daughter Nina will read the book one day? Whose reaction did you worry about the most when writing the book?

JP: It was my mother that I worried about the most, the fact that she would now know that I had sex with my husband and in what positions. As far as Nina goes, I think by the time she decides it’s cool to read mummy’s book I’ll be demented and in a nursing home, being an older mother and all.

Your book is very funny, especially for such a serious subject. Was the experience of infertility only funny in retrospect, or have you always used humor to deal with things?

JP: It is pretty much a survival technique for me, to lampoon anything I find scary. It gives me back a sense of power in situations over which I have no control. You know, I may not beat you but at least I can poke fun at you.

[Part two to follow.]