[A continuation of our Resentment Watch series.]

In my last post, I described the anti-humanism of utilitarian philosophers like Peter Singer, who more than rhetorically ask the question of whether humans should exist. While I don’t believe (as, say, Wesley J. Smith does) that Singer’s anti-humanism is now characteristic of the West in general, Singer’s apparent loathing of human existence in all of its supposed misery is at least shared by many transhumanists.

The discussion thread for a recent post here exploring the full human phenomenon of breathing illuminates the point. Commenter IronKlara says,

You sound like you actually *like* being trapped in these meat cages. And like you think it’s bad to want to escape a cage that does pretty much nothing except find new ways to hurt and malfunction.

It’s hard to see how we could contrive new good things outside our “cages” if all we know is inside them and all that’s inside them is bad.

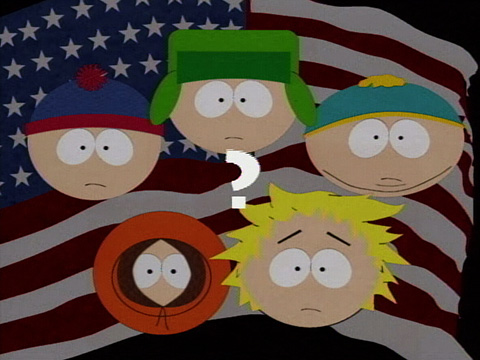

Similarly, commenter Jonathan is concerned about “the loss of life (particularly infant life) that cerebral hypoxia causes each year,” invoking a utilitarian calculus to claim that “the good of preventing an infant death outweighs the good of those joys of breathing to which Schulman refers.” Commenter tlcraig, whose comments on this thread are smart and funny, aptly asks, “How does this help me to decide whether being without breathing would be a better way for me to be?” Not only does it evade the central question, but if you tease out Jonathan’s comment, it amounts to claiming that if I like breathing, I support allowing infants to die, which veers into South Park farcical political ad territory (“If you support this, you hate children. You don’t hate children … do you?”).

To put it mildly, of course, the “breathing versus dead infants” idea is what they call a “false choice,” and one that, aside from its odiousness, manages to put the problem precisely backwards. If there are infants with cerebral hypoxia, or anyone with any sort of hypoxia for that matter, the problem is that they have a fundamental need they are unable to meet, and that we should focus our medical efforts on helping them meet it. The commenter seems to be saying, however, that if someone has trouble breathing, then instead of eliminating the trouble, we should eliminate the breathing.

Okay, but what’s left over once we do — particularly if we consistently apply this standard of eliminating rather than fulfilling needs? One would have to say we should do away with arms because some babies are born without them, and do away with sight to accommodate the blind. For that matter, if this idea is really fully and consistently applied, one would have to say we should eliminate all needs, and do away with life, because so much death results from it. And so at the root of this utilitarian transhumanist argument we find the same anti-humanism as we did at the core of Singer’s: the ostensible concern for eliminating suffering hollows out our understanding for why we should even be alive. Rather than maintaining aspects of our humanity like breathing, it’s the whittling away of everything that is essentially human from our self-understanding that poses the real threat to our existence.

Futurisms

July 2, 2010

You sound like you actually *like* being trapped in these meat cages. And like you think it’s bad to want to escape a cage that does pretty much nothing except find new ways to hurt and malfunction.

I'm a transhumanist and I rather like my "meat" body, thank you very much.

Oy, that's a shot across the bow if I ever saw one. But I appreciate having made it to the front page at least! (One factual point- I get the impression that you're interpreting cerebral hypoxia as a chronic condition. Let me be clear that I also refer to carbon monoxide poisoning, choking, etc.)

Mr. Schulman, as I said before, I respect your love of being human. I even share it, in a conditional way. (I made this clear as well, which makes me wonder why I made it to the 'resentment watch' series in particular.) But it seems to me that there are far better things than being human. Personhood, the capacity to experience, to understand, to reason, to choose, to act, to exist as a self.

To breathe is to gamble all of this- ALL of it- on the fact that the space directly outside your head will continue to contain a precise mixture of gases, at a precise temperature and pressure, and that over the course of a lifetime, the (glorious) machine that turns those gases in to continued life will never fail or be obstructed. You know as well as I do, Mr. Schulman, that these conditions do not and never will hold true for every person at every time, so please don't accuse me of some sort of false choice. To embrace breathing as a necessary part of being a person is to embrace fragility (and, yes, infant death) as some sort of regrettable necessity. Is this not a valid answer to tlcraig's question?

You seem convinced that the human condition is our only possible source of meaningful experience and positive good. To you, our distance from humanity as it stands in this one moment in time is a measure of loss, that we might as well be chopping off our arms and plucking out our eyes. This is incorrect, and you truly are choosing stasis and loss. Let me see your South Park and raise you Blade Runner:

"I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain."

Some of this is good advice for considering how to approach enhancement sensibly, thanks.

I presume that if people would not choose to get rid of breathing unless they could replace it with a continuous experience equally interesting and fulfilling.

Can you imagine such a thing?

@Jonathan: If you place the highest value on the abstractions of personhood, experience, and the like, then what are the sorts of things that persons have experiences of and that existing selves do that fulfill no needs, and have no requirements that can ever fail to hold under any conditions? (You paint quite a picture with that "gamble," though. How often does "the space directly outside one's head" spontaneously cease to contain air?)

@Michael: What would it take for an experience to be as "interesting and fulfilling," in at least the same ways, as breathing?

Ari, it would take a lot of investigation, theory, and experimentation to find out. That's part of the excitement. It needn't be the exact same — f it were, why bother in the first place? People will be looking for new experiences, though.

There are plenty of things that leap to mind- artistic endeavor, the pursuit of mutually fulfilling relationships, interpersonal competition, the acquisition of new experience and knowledge…

These things depend on certain factors- I can succeed or fail at them. But if the art doesn't work out, I can always try again, or try something else. If I fail to respirate, that's not so- why accept a finite gain for the ultimate risk?

(You seem to be implying that risks such as choking and carbon monoxide poisoning simply don't exist? I don't know how to respond to that.)

I get the feeling that Prof. Singer is being attacked for other reasons than his thoughtful review of Benatar's book.

While it is tempting to reject Benatar's thesis reflexively as morbid and misanthropic, as a father of two I too have my doubts about whether my children should thank or curse me. After all, for the joy of today's toddler (and it is hardly all joy) learning to live, there will be grief aplenty tomorrow, and my little boy will one day (when I am gone, I selfishly hope) have to face his own mortality, alone.

Singer, for his part, after giving Benatar his due consideration, concludes that he does not agree: "In my judgment, for most people, life is worth living." What loathing of human existence is apparent in that? What more could you ask for? That we not think at all about such questions?

I don't think it's a coincidence that most people who promote the deranged idea that we should enjoy having our souls trapped in these meat cages belong to the sex which does not menstruate.

Hey, it's not so bad for you guys, so how dare we complain about recurring incurable agony? Plus the fun of childbirth! And being too weak to defend ourselves from you! We should humbly accept your word that this is, in some mysterious way we cannot understand, a good thing.