The owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the falling of dusk.

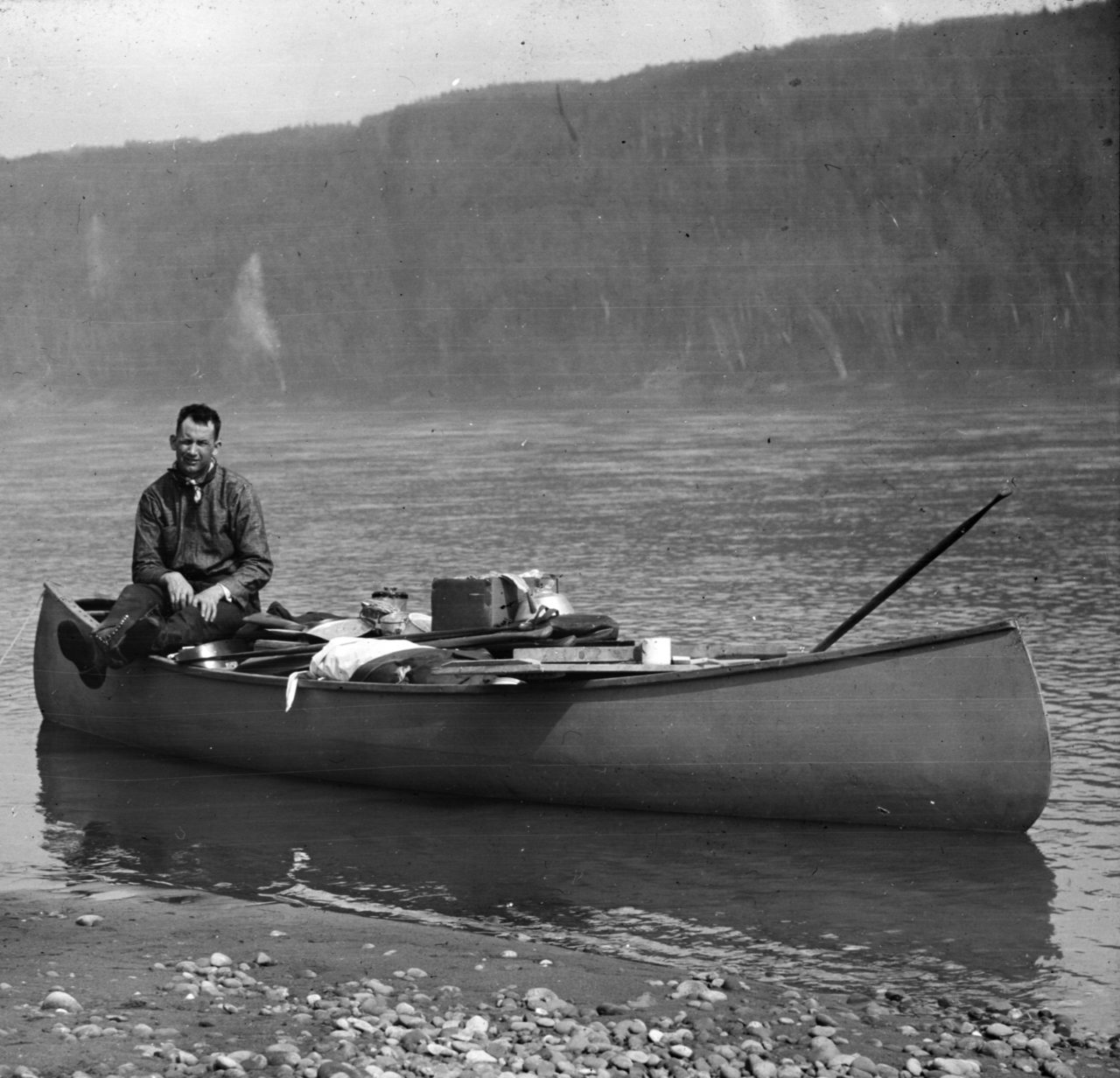

On the evening of May 25, 1947, the fellows of the Royal Society of Canada — the country’s leading scientists, artists, and intellectuals — gathered at the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City for a much-anticipated event: an address by the society’s president, Harold Adams Innis. Innis was at the time a renowned academic in Canada and one of the most prominent political economists in the world. Through a series of expansive, meticulously researched books and articles tracing the development of basic Canadian industries — rail transport, fur trading, fishing, timber, paper — he had shaped his country’s understanding not only of its economy but of its history and culture. The assembled dignitaries were eager to hear where the great scholar would take his work next. But the talk, entitled “Minerva’s Owl,” fell flat. A tedious, convoluted disquisition on knowledge and communication, seemingly disconnected from Innis’s earlier work, it left the audience baffled and disappointed.

It wasn’t until four years later, when the lecture was published as the opening chapter of Innis’s book The Bias of Communication, that it began to attract interest. Although it remained a challenging and often frustrating work in its written form, “Minerva’s Owl” was also, for patient readers, a revelatory one. It made clear that Innis was engaged in a far-reaching exploration of the role of communication systems in shaping societies and their destinies. Drawing on examples ranging across the ages, from the etching of cuneiform characters on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia to the use of radio as a propaganda tool in the years leading up to the Second World War, he explained how the arrival of a new communication medium often triggers “cultural disturbances” that alter the course of history. Media are much more than channels of information. They’re instruments of political influence and imperial power, sculptors of civilization.

With its emphasis on media’s formative role in a society’s development, “Minerva’s Owl” would come to be seen as a founding document — maybe the founding document — of the academic discipline of media studies that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1964, the celebrated media savant Marshall McLuhan, who like Innis was a professor at the University of Toronto, wrote that he saw his own recent book, The Gutenberg Galaxy, as “a footnote to the observations of Innis.” The distinguished American educator and media theorist James Carey called Innis’s work “the great achievement in communications on this continent.”

Innis would not live to hear such praise. In 1952, the year after publication of The Bias of Communication, he died of prostate cancer, just fifty-eight years old. Unlike McLuhan, whose provocative work maintains a cultural currency, Innis and his more esoteric musings are today unknown to the general public. His name is rarely heard outside academic offices, conferences, and journals. But his ideas deserve a fresh look. Even though he died before he was able to complete his study of communication and civilization, his writings from seventy-five years ago shed an unexpectedly clear light on the media-induced cultural disturbances that trouble us today.

Communication systems are also transportation systems. Each medium carries information from here to there, whether in the form of thoughts and opinions, commands and decrees, or artworks and entertainments.

What Innis saw is that some media are particularly good at transporting information across space, while others are particularly good at transporting it through time. Some are space-biased while others are time-biased. Each medium’s temporal or spatial emphasis stems from its material qualities. Time-biased media tend to be heavy and durable. They last a long time, but they are not easy to move around. Think of a gravestone carved out of granite or marble. Its message can remain legible for centuries, but only those who visit the cemetery are able to read it. Space-biased media tend to be lightweight and portable. They’re easy to carry, but they decay or degrade quickly. Think of a newspaper printed on cheap, thin stock. It can be distributed in the morning to a large, widely dispersed readership, but by evening it’s in the trash.

Because every society organizes and sustains itself through acts of communication, the material biases of media do more than determine how long messages last or how far they reach. They play an important role in shaping a society’s size, form, and character — and ultimately its fate. As the sociologist Andrew Wernick explained in a 1999 essay on Innis, “The portability of media influences the extent, and the durability of media the longevity, of empires, institutions, and cultures.”

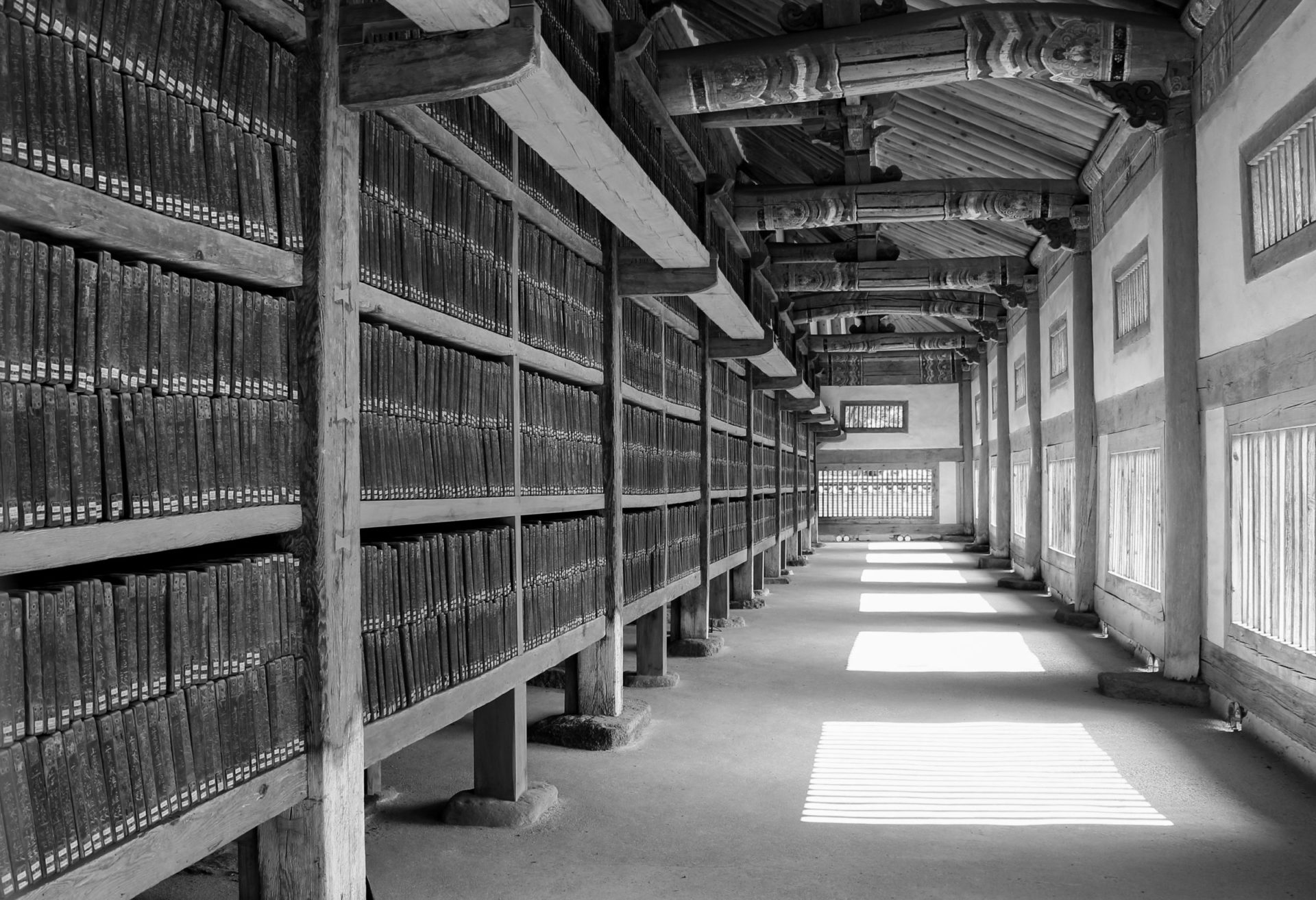

In societies where time-biased media are dominant, the emphasis is on tradition and ritual, on maintaining continuity with the past. People are held together by shared beliefs, often religious or mythologic, passed down through generations. Elders are venerated, and power typically resides in a theocracy or monarchy. Because the society lacks the means to transfer knowledge and exert influence across a broad territory, it tends to remain small and insular. If it grows, it does so in a decentralized fashion, through the establishment of self-contained settlements that hold the same traditions and beliefs.

When space-biased media become dominant, a society turns expansionary, and its cultural emphasis shifts from sustaining tradition to pursuing progress. Breaks with the past are not only tolerated but celebrated as welcome innovations. What holds people together is no longer shared beliefs — as the territory expands, a variety of cultural values and practices need to be incorporated into the polity — but rather laws and regulations imposed by central authorities. Administrators take command, and they use the instruments of communication to exert their control at a distance.

No medium, Innis stressed, is purely time-biased or space-biased. Each exists on a continuum of durability and portability. A heavy, engraved stone can be moved, given enough effort, from one place to another. (Moses managed to get his tablets down a mountainside.) Back issues of a daily newspaper can be stored for reference in a library or archive.

Similarly, in any community there is always a tension between the maintenance of tradition and the pursuit of progress, between stability and change, insularity and expansiveness. This tension manifests itself in different modes and tools of communication, and as the variety of available media grows, so too does the tension. What’s crucial to a society’s vitality and longevity, Innis argued, is keeping the tension constructive rather than destructive — maintaining a balance between time-biased and space-biased communication. When there is too much emphasis on continuity and stability, a society grows stagnant and moribund. When there is too much stress on growth and change, it loses its cohesiveness and purpose and drifts toward decadence. An out-of-balance society is an ill society.

The story of civilization since the invention of writing several thousand years ago is, among others, a story of changes in writing materials. Even though writing itself might be said to be a time-biased technology, as it allows a record of events and thoughts to persist independently of the lives of the observer and the thinker, innovations in writing media have been aimed mainly at extending information’s reach, often at the expense of its durability. Stone and clay tablets were supplanted by more portable but still cumbersome papyrus scrolls and parchment codices, and those in turn were supplanted by lightweight paper documents. As city-states and nation-states sought to extend their territories and influence, the spatial transport of information took precedence over its temporal transport. In another book, Empire and Communications (1950), Innis wrote:

The sword and pen worked together…. The written record signed, sealed, and swiftly transmitted was essential to military power and the extension of government. Small communities were written into large states and states were consolidated into empire.

The mechanization of written communication — with printing presses supplanting scribes — further sped information’s passage across land and sea.

Most of us, our perspective shaped by the Enlightenment, see the material history of written communication not as a fraught story about geopolitical power and conflict but as a happy one about the spread of knowledge and understanding. As a political economist in a country situated in the shadow of empires — first British, then American — Innis took a less sanguine, more conflicted view. He appreciated the many benefits that come with freer flowing information — an acceleration in scientific and technological discoveries, notably. But he also remained alert to how media can serve as channels of propaganda, arms of autocracy, and instruments of manipulation and control. What flows through communication systems, he saw, is not just thought but power. Minerva was the goddess of wisdom but also of warfare.

He also understood that the biases of communication shape human perception. Not only do they alter how people think; they alter how people think about thinking. Contemporary society was, in its obsession with conquering space, losing its sense of time, Innis believed. With information flooding in from near and far, people were falling victim to “present-mindedness.” They were so busy consuming new information that they had no time to step back and view the information in a broad historical and cultural context. Overwhelmed by immediate concerns and diversions, they shunned the hard, slow work of interpretation.

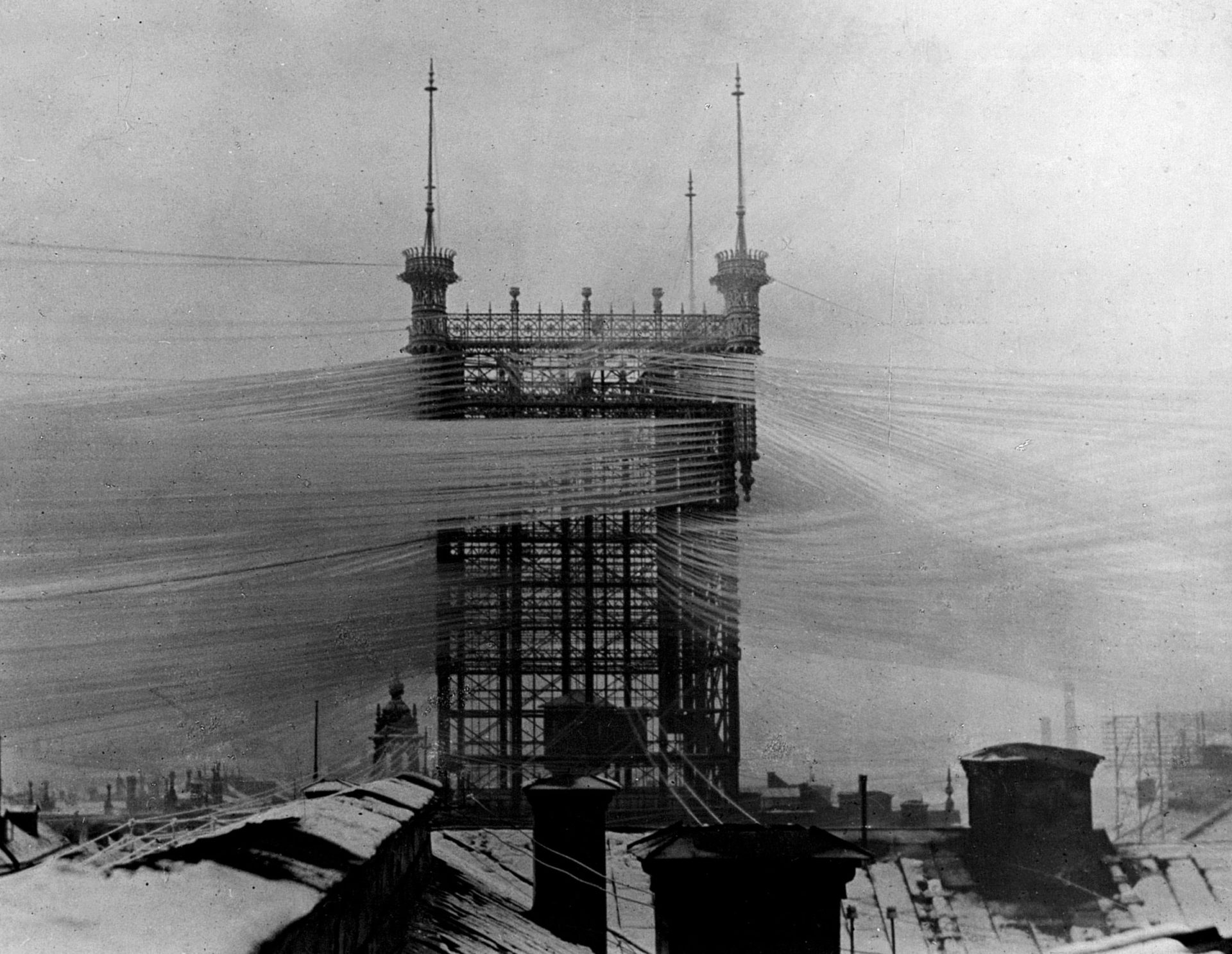

The rapid commercialization of communication in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the attendant expansion of media into telecommunications and broadcasting, exacerbated the problem. In seeking a return on large capital investments, the companies building and operating media empires — in television, radio, and publishing — had a strong financial incentive to keep their customers in the flux of the new. Slowing down the mind, broadening a person’s view beyond the moment, was bad for business. As Innis wrote in Changing Concepts of Time, his last book, he feared that large media companies were becoming “monopolies of communication” engaged in “a continuous, systematic, ruthless destruction of elements of permanence essential to cultural activity.”

Near the end of “Minerva’s Owl,” in a rare moment of concision, he summed up his view: “Enormous improvements in communication have made understanding more difficult.” With that one startling and seemingly paradoxical sentence, he called into question a foundational assumption of modern media and, indeed, modern society: that an abundance of information brings a wealth of knowledge. Information and knowledge, he saw, could be adversaries.

Forty years after Innis’s death, the arrival of the Internet seemed to herald a new era for media, one that would at last bring the temporal and the spatial into harmony. The net was a communication system of unprecedented scope: a world wide web that could transmit huge amounts of information across the planet. But unlike traditional broadcast networks, it was also a storage medium of unprecedented depth. It promised to contain, and provide easy access to, the entirety of cultural history, from ancient texts to pop songs. And because the network was designed to be decentralized, a mesh of interconnected nodes, it seemed obvious that it would resist attempts to impose state or corporate control over its workings. Information would be free; communication democratized. Connected to the net’s intellectual bounties, people would be able to make sense of the complexities of the present by viewing them in the context of the past.

The early, idealistic view of the Internet proved an illusion. The system went out of balance almost immediately, its spatial reach subverting its temporal depth. Far from alleviating our present-mindedness, the net magnified it.

Innis would not have been surprised. Information in digital form is weightless, its immateriality perfectly suited to instantaneous long-distance communication. It makes newsprint seem like concrete. The infrastructure built for its transmission, from massive data centers to fiber-optic cables to cell towers and Wi-Fi routers, is designed to deliver vast quantities of information as “dynamically” as possible, to use a term favored by network engineers and programmers. The object is always to increase the throughput of data. When the flow of information reaches the consumer, it’s translated into another flow: a stream of images formed of illuminated pixels, shifting patterns of light. The screen interface, particularly in its now-dominant touch-sensitive form, beckons us to dismiss the old and summon the new — to click, swipe, and scroll; to update and refresh. If the printed book was a technology of inscription, the screen is a technology of erasure.

The medium’s technical characteristics have been shaped by commercial interests. The evolution of the Google search engine, for the last quarter century humankind’s most valued epistemic tool, tells the tale. For several years after it was founded in 1998, Google, inspired by the rigor of what its two grad-student founders called “the academic realm,” pursued a simple goal: to find the highest-quality sources of information on any given topic. Through an analysis of hyperlink history — a proxy for the citation analysis used in evaluating scholarly literature — the search engine promoted information that stood the test of time. The deeper into the past the software reached, the better the results it returned. To use Google in its early days was like having the world’s best-informed archivist at your beck and call.

Once the company began to seek profits through advertising, its focus shifted. It began to view search results as media content. The goal was less to inform people than to engage them as an audience. In 2010, Google rolled out a revamped search system, code-named Caffeine, that placed enormous new emphasis on the recency, or “freshness,” of the results it delivered. A year later, in a post on Google’s corporate blog, the company’s head of search, Amit Singhal, explained the rationale for the shift:

Search results, like warm cookies right out of the oven or cool refreshing fruit on a hot summer’s day, are best when they’re fresh. Even if you don’t specify it in your search, you probably want search results that are relevant and recent.

The company had come to realize that information, when served up as a commodity for instant consumption, loses value quickly. It gets stale; it rots. The past is far less engaging, and hence monetizable, than the present. To use Google today is to enter not an archive but a bazaar.

The social media companies that began to emerge around the same time as Google were aggressively space-biased from the start. Bringing Innis’s worst fears to pass, they sought to capitalize on “network effects” to build empires of information and establish monopolies of communication. Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg declared, wouldn’t be satisfied until it had built a “global community.” It would own and operate the world’s “social infrastructure.” The Internet, he and other net entrepreneurs understood, may not have any physical center, but central control can still be wielded through identity systems, sorting algorithms, and other proprietary software routines and protocols. When people sign in to a social network, they become not just its customers but its serfs.

Before the smartphone became the default mode of access to social networks, when they still operated only as websites, most platforms arranged posts in reverse chronological order. That is, the newest status update, comment, or photo always took precedence, appearing at the top of the feed and pushing all the older ones down the screen and, soon, out of view. The ordering gave strong emphasis to the present, but it still carried a hint of the temporal. It still situated information in time. In scrolling through posts, a user traveled backward into the past, even if the past didn’t extend beyond a couple of hours or days. When the platforms retooled their feeds for the phone’s continuously updated touchscreen, they happily jettisoned the “rev chron.” Today’s feed algorithms give priority to whatever bit of information is calculated to have the highest odds of gaining a momentary purchase on a user’s attention.

Immediacy is the all-important criterion. Time has disappeared. The information that pours through social media today “is relevant only fleetingly,” writes the philosopher Byung-Chul Han. “It lives off its capacity to surprise.” As soon as the surprise has been delivered, the next one is served up. There is no past or future on TikTok or Instagram or X. There is only now.

Innis’s critics often labeled him a technological determinist. But he was a realist. Technology’s effects, he saw, cannot be isolated from economic and political forces, much less the vagaries and perversities of human nature. He always took care to view the machinery of communication in the context of history’s repetitions and disjunctions. The breadth of his perspective at times gives his writing a fragmentary feel, but in its sensitivity to social and technological complexity, his work offers a powerful model for understanding why digital media has taken us down a path so different from what we expected. Despite the archival riches and the decentralized architecture, the net’s emphasis on the light-speed transmission of data for commercial gain, combined with our all-too-human hunger for diversion and distraction, has given rise to information empires of unprecedented scope. Our new emperors give us all the information we can consume but starve us of knowledge.

What Innis doesn’t offer is much hope that we’ll be able to change course. His writing on communication is melancholic in tone and pessimistic in thrust. He saw present-mindedness as a comfortable trap. By foreclosing the long view, it blinds us to what we’ve lost. It breeds an arrogant belief in the present’s superiority to the benighted past. Fashionable orthodoxies take hold of the public mind, as thought begins to run in the “grooves” carved out by the dominant media channels. Though Innis devoted his career to exploring the culture of the West, he also sensed its demise. “Concern with the position of Western civilization in the year 2000 is unthinkable,” he wrote in 1951. “Each civilization has its own methods of suicide.”

Still, even in the gathering dusk, a glimmer of light shines through. Deeply versed in classical history and philosophy, Innis venerated the oral traditions of conversation and debate, teaching and tutoring, that formed the heart of ancient Greek culture. In their intimate, human scale, he saw an antidote to mechanized media, a means of escaping the dominion of information empires. A spoken word may be as evanescent as a tweet or a snap, but the acts of talking and listening — together, in one place — remain unmatched as vehicles for critical, creative, and communal thought. They serve to test and refine knowledge even as they carry it, from one person to another, through time. A reinvigoration of the oral traditions, Innis suggests, may be our last defense against the tyranny of now.

Keep reading our Winter 2025 issue

How the System Works • Make Suburbs Weird • The New Control Society • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?