An avowed sun worshipper, the neurosurgeon Jack Kruse has skin the color of a Christmas ham. His cheeks emit a neon glow that, when coupled with his white goatee and slicked-back hair, makes him look like Santa, if Santa crash-landed in Belize and decided to stay. He favors a shotgun approach to speaking, hitting the Cambrian explosion and the atomic structure of cells in one volley, then knocking out the medical establishment in equal parts jargon and insults. Like President Trump, he hails from New York, says huge as yuge, and likes to fire off big-if-true statements: “We make more powerful light than the sun creates” and “When Apple made their AirPods, their iPads, their earplugs, the new VR glasses, and the iPhone, that was a million times worse than the atomic bomb that happened in Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945.”

Kruse believes that most modern human diseases can be traced back to the replacement of natural light with artificial. Or, as he puts it, “True alchemists do not change lead into gold; they change sunlight into health span.” There’s more, of course: dietary recommendations, a Patreon blog, plugs for a medical resort in El Salvador, ice baths, Bitcoin, magnets, and many thoughts on decentralization. But the use and misuse of light is the foundation.

Even in the colorful world of health influencers, Kruse stands out. Plenty of cosplay cavemen recommend starting each day by getting an eyeful of the rising sun, but Kruse argues that exposure to the wrong kind of light is the foremost cause of obesity, insulin resistance, colon cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and a host of other pathologies. A vague mistrust of electromagnetic fields permeates alternative health circles, but Kruse claims that Hollywood’s VHF and UHF emissions have created a third Van Allen radiation belt around Earth that so interferes with sunlight that many Californians cannot synthesize adequate vitamin D.

It’s easy to dismiss influencers as charlatans or grifters, not just the Kruse fringe but the Silicon Valley types who quantify the quality of their sleep, the quality of their bowel movements, and everything in between, the athletes hawking bespoke exercise programs guaranteed to pack on thirty pounds of lean muscle, the sober doctors pausing their four-hour podcasts to advertise a pharmacy of supplements. Many of them doubtless are charlatans and grifters.

Yet they are also obviously right when they point out that the health care system has failed in the face of burgeoning obesity, hypertension, heart disease, gout, diabetes, and all the other conditions that make up what the medical literature sometimes calls the “diseases of civilization.” Even as the absolute length of the average life has increased, its quality has not. Rather than seeking to increase and prolong health, treatments like insulin for type 2 diabetes focus on prolonging life in a state of managed illness rather than curing it. What personalities on TikTok and YouTube and Spotify offer is an alternative. It might involve rigorous science, a scientific revolution, or no science at all. But in each case it is an effort to encourage living instead of capitulation.

We find ourselves in a wilderness of alien plenty and alien threats, of food that is ubiquitous, delicious, and laced with microplastics, of drugs in our drinking water, and proliferating screens. The paradox of our predicament is captured in two terms, both apposite and opposite. We label a group of conditions “diseases of civilization,” for they obviously are a product of modern, industrialized society. We also call them “lifestyle diseases,” for it is every bit as true that they are the product of individual choices: about diet and exercise, work and play, sleep and stress, relationships and loneliness.

We can fairly blame the world we are in for the increasing incidence of everyday pathologies, even as the pathologies demand a response of each of us. Ill health may be driven by environmental changes broadly, but we must each try to wrest control for ourselves. The problem is both obvious, in that something big has changed, and obscure, in that no one knows exactly what that something is. Each of us must make our own way, and the only thing worse than following a false prophet might be following no prophet at all.

Peter Attia hosts a hugely popular health podcast and runs a private practice so exclusive that the most conspicuous evidence of its existence is the number of celebrities like Hugh Jackman, Chris Hemsworth, and Oprah Winfrey who promote his work. Despite this, his origin story is remarkably common. Here’s how he describes it in his 2023 book Outlive: “On September 8, 2009, a day I will never forget, I was standing on a beach on Catalina Island when my wife, Jill, turned to me and said, ‘Peter, I think you should work on being a little less not thin.’” In addition to being overweight, or, as he puts it, “sausage-like,” Attia was developing insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes.

These days Attia is very fit, very bald, and very purposeful. He is a wonderfully clear communicator of science, despite verbal tics that suggest too much time with tech bros — he likes to “double click” on ideas — and being buried in papers on the biochemistry of proteins, as evinced by his penchant for describing himself as “phosphorylated” when he means “pissed off.” He has scrupulously documented his own health journey, featuring, among many other self-experiments, extreme carbohydrate restriction, an aggressive fasting schedule, the use of a variety of drugs with plausible but uncertain benefits, and always a masochistically regimented exercise program. But despite the all-consuming, successful, and public nature of his response, the broad contours of his struggle — of arriving at middle age overweight and with early signs of lifestyle illnesses — are as American as ordering a Big Mac with fries and a Coke, then circling back around the drive thru for an apple pie.

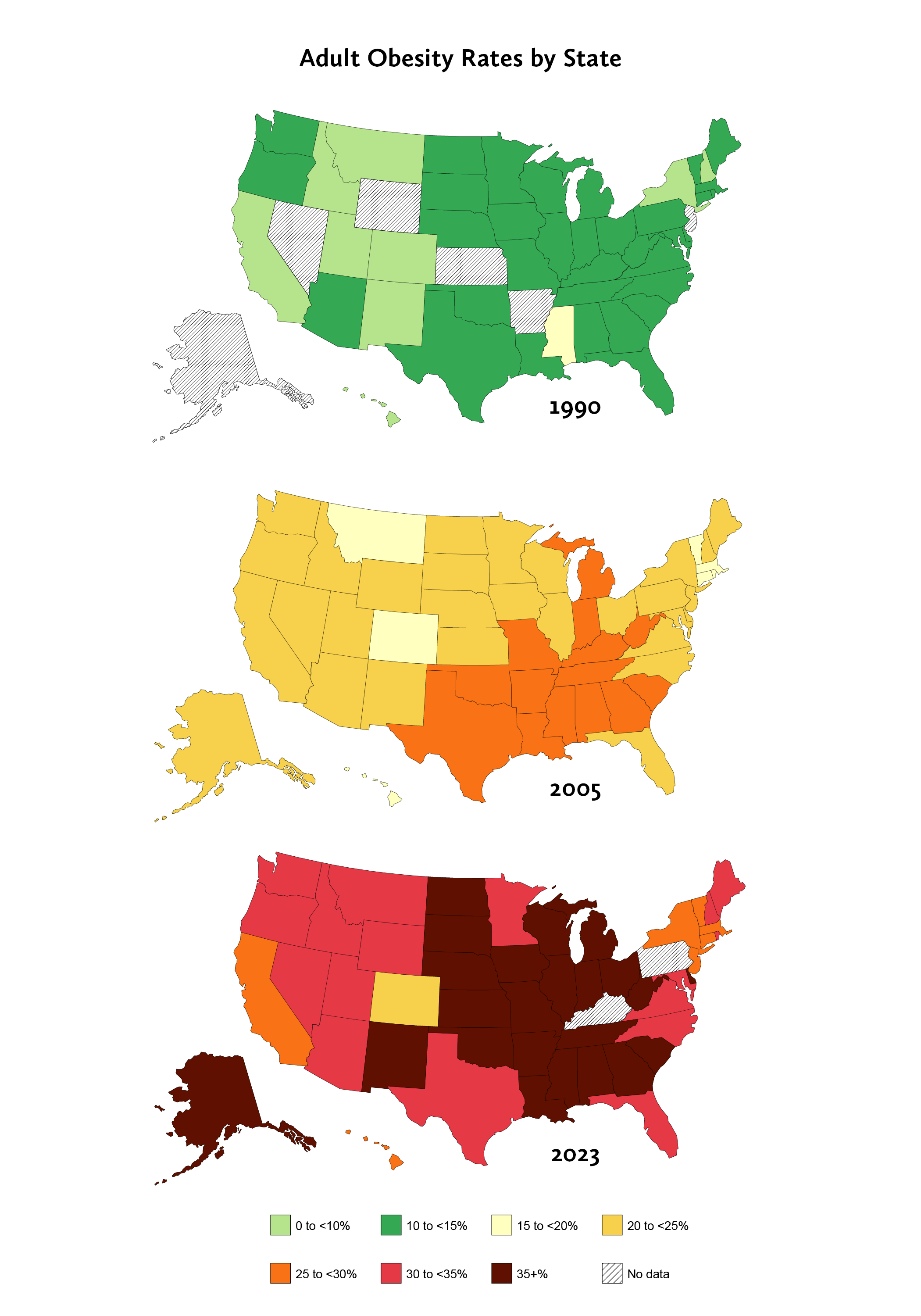

A study published in November in The Lancet found that three-quarters of American adults are now above the healthy weight range. More than 40 percent of men and nearly half of women are obese. Rates of childhood obesity, which hovered at around 5 percent until roughly 1980, have since increased to about 20 percent. The trend is global, and in BMI as in military power, America’s edge is diminishing. Obesity rates on several Polynesian islands top 60 percent, and countries as disparate as Qatar, Romania, and Argentina are at over 35 percent. The global health impact of obesity has surpassed that of malnutrition. While obesity on its own negatively impacts quality of life, it also often comes with comorbidities. Half of all Americans are diabetic or prediabetic. About a quarter of Americans have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, which is the fastest-growing reason for needing a liver transplant.

In his book and on his podcast, Attia argues that metabolic dysregulation significantly increases the risks of not just liver disease but cardiovascular disease, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease, which collectively account for the bulk of deaths in America, and untold suffering. The medical system, in his view, is hopelessly reactive. Decreased rates of smoking have reduced the incidence of lung cancer, but instead of exploring behavioral interventions that could lead to similarly profound improvements in other areas of health, most doctors passively wait for lifestyle diseases, which are almost always slow-moving, to become full-blown crises before addressing them.

In addition to being an M.D., Attia is a former McKinsey consultant, and his efforts to extend both lifespan and years of functional health rely on the idea that more data is always better. He wants the science of human health to be its best, most beautiful self, to be bold and proactive. Even though it almost always comes up short, he still loves it and considers it the only way of knowing anything worthwhile. Despite the very real limits of our knowledge, in Dr. Attia’s telling the most pressing issues with health care are about acting on what we already know rather than discovering new knowledge. But radical reform and restructuring would be needed to make the system function how he would like it to, and so he treats his exclusive clientele while also freely disseminating his ideas. The consistent subtext of his podcast and his book is that the health care system cannot deliver high-quality preventive care, which means that anyone interested in living the healthiest, longest life possible will have to take the initiative.

Like the Department of Health and Human Services, he recommends exercise, but he recommends more intense exercise focused on clear outcomes: Moving your VO2 max — the amount of oxygen you can absorb per volume of body mass — from poor to elite level will decrease your all-cause mortality five-fold over the course of a decade. Like the FDA, he recommends balanced nutrition, but he is unsparing in articulating the bad effects of consistent overindulgence and consumption of “garbage” foods. He will explain at great length why he believes that an ApoB protein test should supplant the standard lipid panel as the default for assessing a patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease.

He comes across as the general practitioner you wish you had: conscientious, attentive, patient, and prepared to walk with you as you undertake the difficult process of change. To bolster his advice he marshals armies of evidence, from mechanistic explanations of the effects of aerobic training on energy partitioning to lengthy discussions of the catastrophic risk posed by falling after the age of 65. He is the rare health influencer who does not sell supplements and does clearly document potential conflicts of interest. He also takes pride in discovery and revision. Data convinces him to reevaluate his beliefs, his recommendations, and the way he lives.

Perhaps his tacit assumption that others share his capacity to change in response to new evidence explains why, for someone so interested in root causes, Attia pays such little attention to the root causes of the problem on the larger scale. In the middle of his book he does acknowledge it: “The conundrum we face is that our environment has changed dramatically over the last century or two, in almost every imaginable way … while our genes have scarcely changed at all.” But the handful of pages he devotes to the subject are notably superficial when compared to the hundreds of pages that precede it, in which he describes the biological underpinnings of lifestyle diseases, and the hundreds of pages that follow, in which he lays out dozens of tactics for addressing them.

If all the obesity and diabetes and cancer and heart disease have resulted from human tinkering with the food system and the lived environment, then trying to implement overdetermined and granular prescriptions — liable to shapeshift with each new study — can look needlessly complicated when compared to simply rolling back the clock.

The Liver King, née Brian Johnson, has a radical idea of how to eat and live, an idea so dumb it might be brilliant. What if, he asks, you chose to live as you imagine our ancient ancestors did (with only a passing interest in how archeological evidence and present-day hunter-gatherers show they actually did)? Short, shirtless, and steroidal, this remarkably charismatic piece of beef jerky exhorts his 6 million TikTok followers to adhere to nine ancestral tenets, which include copious sun exposure, eating raw meat, and getting filmed picking up massive chains by the fathom. He also likes to trot out New Age pablum about balance and bringing each particle of his being into alignment with the cosmos.

Though vaguely science-y language does occasionally sneak in, it is incidental. The proof is self-evident. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a clip of a ripped little dude carrying kettlebells while pulling a weighted sled across the deep end of the pool is worth a thousand studies. The most straightforward interpretation of the Liver King is that he provides delusionally aspirational entertainment. The same mental elision that connects buying a lottery ticket to sitting on a yacht connects buying encapsulated beef thyroid to being musclebound and possessed of pathological self-confidence. The chain of causality, let alone the evidence for it, couldn’t be less relevant. But he is nevertheless compelling. It’s hard to watch the Liver King for long without thinking that he truly, sort of, completely, sometimes, emphatically half-believes that living in accordance with a superficial idea of nature will lead to optimum health for anyone with the fortitude to do so.

To bolster this case, a liver king less preoccupied with gnawing on bull testicles for clicks might point out the oddest thing about the diseases of civilization, which is that plenty of civilizations and eras have existed without them. Contrary to general notions of Victorian industrial squalor, a 2009 paper in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, “How the Mid-Victorians Worked, Ate and Died,” shows that between about 1850 and 1880, an individual who made it to adulthood in Britain could expect to live as long as an American does today, but with a far lower burden of chronic disease — a lifespan achieved without antibiotics, statins, or any other wonder drugs. Or look at America up until 1980. Despite postwar abundance, rates of obesity remained low. As much as diseases of civilization are framed as issues of personal choice, they are driven by environment. The Boomers didn’t collectively lose their willpower when they turned twenty. The context changed, and they and their descendants changed with it.

An obvious culprit for what has changed is our diet, specifically the increased consumption of ultra-processed food. While surprisingly few studies have examined the topic, there is good evidence that as ultra-processed foods make up a greater share of our diet, rates of obesity go up.

Over the years, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee — appointed by the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and of Health and Human Services — has made recommendations about our food consumption. Many times it has done so in consultation with the food industry that stands to benefit from those very recommendations. Meanwhile, its advice to limit fat, or sugar, or to add fiber, or to get a daily allotment of fruits and vegetables have each come and gone. At times the advice may be sound, but the effect remains dubious. The food pyramid once graced boxes of Frosted Flakes, and its replacement, the MyPlate guide, hangs on the walls of school cafeterias that serve chocolate milk and pizza to growing children.

In 2022, the FDA launched what it describes on its website as:

initiatives to help accelerate efforts to empower consumers with information and create a healthier food supply, such as: developing an updated definition and a voluntary symbol for the “healthy” nutrient content claim, front-of-package labeling, and Dietary Guidance Statements on food labels, as well as establishing recommendations for nutrition labeling for online grocery shopping.

Given the scope of the problem, it’s hard to see how helping to “accelerate efforts to empower consumers” by litigating every square inch of product labels makes any sense.

Companies can use the FDA’s “Generally Recognized As Safe” loophole to add novel ingredients to the food system without rigorous review. The agency will dither over which packaged foods can use the word “healthy,” but it won’t advise the public to avoid packaged foods in the categorical manner of an influencer encumbered by bulging quads and kettlebells rather than bureaucracy and competing constituencies. All the while, the populace slowly but surely gets sicker.

The move away from traditional foods has also come with other changes, which may be contributing to the increasing incidence of disease. Less obvious but still plausible contenders for what’s gone wrong include more sedentary lives, a threadbare social fabric, chronic ingestion of and contact with hundreds of chemicals, overexposure to blue light, and underexposure to the sun. The evidence for these varies from strongly suggestive to speculative, and it’s entirely possible that some or all of them are working in discordant concert with each other.

While the Liver King exists in a superposition of absolute self-parody and absolute earnestness, he compellingly advocates for a diet free from processed foods, plenty of movement, good sleep, time spent in nature, attention to human relationships, and striving to make a meaningful impact. Yes, it’s a spectacle, yes, eating raw meat carries a high risk of pathogens, yes, most of his ideas are completely unrelated to anything that might be called science. But he produces some of the only effective counterprogramming to ads for fast food that the average teenager has a prayer of stumbling across. He competes in the marketplace of ideas. If people are watching his antics, which millions are, and if they are living a little more like the Liver King without going bonkers, which is far less certain, there’s a decent chance their lives are improving as a result.

This modest praise should be tempered with a look at the seamier side of the whole enterprise. The explicit premise is that anyone can become the king of his own liver kingdom by living like the one true monarch. But while he talks endlessly about the need to put in the work, the Liver King makes his money by selling a shortcut. For the guy who can’t spend all day charging around on a dusty ranch and can’t stomach eating glistening globules of thymus gland, taking the Liver King’s freeze-dried beef organ supplements might be enough to spark a transformation into a liver baron or liver viscount.

More damning, particularly when considering his suitability as a role model for young men, is the utterly predictable scandal in which it was revealed that he was spending thousands of dollars per month on steroids. Beef liver may be food fit for royalty, but on TikTok it takes synthetic testosterone and growth factor to look the part.

It would be an overstatement to say that Jack Kruse, with his cosmically decentralized vision of health, Peter Attia, with his spreadsheets of data, and the Liver King, with his syringe in one hand and a chunk of spleen in the other, are non-overlapping magisteria. But, besides talking to large online audiences about health, it is true that they don’t have much in common.

Other influencers are more ecumenical in their approach. The most prominent example is Andrew Huberman, a burly Stanford neurobiology professor with 7 million Instagram followers, 6 million YouTube subscribers, and a podcast that, as of this writing, tops the U.S. charts for health and wellness. Huberman will share episodes with Attia in which they discuss studies with some rigor, but he will also join Kruse for nearly seven obsequious hours, as ready with a “yes, and” as a theater kid at his first comedy improv workshop.

Like the Liver King, Huberman is not simply a do-gooder out to help people live healthier lives. He starts his podcast episodes announcing his commitment to sharing no-cost and low-cost ways to live better, which invariably transitions directly into an advertisement, most often for a pricey powdered vegetable drink, the benefits of which he describes with precisely the same avuncular authority he uses to discuss the neurochemistry of taking an afternoon nap. But no one can claim he doesn’t also deliver on the free stuff.

Huberman, or at least the public Huberman that appears in podcasts and interviews, has an innocent, puppy-dog positivity. He goes into every situation expecting to share his awed amazement at both his and his interlocutor’s brilliance, and he’s never disappointed. Whether he is talking to another doctor about how to regulate blood sugar, or to Kruse about how mitochondria break the second law of thermodynamics, he cultivates a tone of both expertise and shared discovery. For Huberman, science is less a painful, fallible, incremental process than an inexhaustible source of cool factoids that translate directly into lists of self-improvement actions. The defining idea of his project is that every area of human life, no matter how obscure, can be improved by a protocol. From sleep to waking to parenting to mental focus to relaxation, science gives Huberman — and Huberman gives his audience — straightforward steps to take control.

One vexing aspect of lifestyle diseases is the sheer number of discretionary aspects of an individual life they might involve: food, exercise, sleep, stress, work, technology, relationships. This is why Huberman’s proceduralism, for all the questionable science that may underpin it, looks like one reasonable response to the problem of sustained behavioral change.

Food is an obvious example. It is not so hard to avoid the donuts left in the office break room. It is not so hard to pack a lunch instead of going out for fast food. It is not so hard to buy a black coffee instead of a soda at the gas station. It is not so hard to stick to a shopping list of healthy foods at a supermarket. But it is incredibly hard for most of us to do all of these things all the time, day after day. The food environment encourages a default that is unhealthy. Huberman’s evidence for the physiological benefits of limiting food intake to an eating window of four to six hours each day may be slim, but a person who does so reduces the number of discrete food choices that must be made.

Or take sleep. His evening and morning protocols may be more ritual than hard science, but ritualized behaviors are easier to repeat. If an elaborate bedtime routine is what it takes to stop scrolling Twitter, then it’s worth doing.

Even Attia, who does a good job of laying out the empirical evidence for his claims and who regularly changes his mind based on new evidence, provides at least as much motivation as education. Revisiting the importance of resistance training for the tenth time might add a little nuance to a lay understanding, but I suspect the reason most people tune in — certainly the reason I do — is to hear him, as an avatar vested with trust and authority, reaffirm that the same old hard choices are worth making again and again. His podcasts are as much inspiration as science, or, more charitably, inspiration by way of science delivered with considerably more nuance and fidelity than most others are wont to employ.

The situation is hilarious and heartbreaking and utterly absurd. As a byproduct of generating incredible abundance, industrial society has made millions of us ill. Because the exact mechanisms by which it has done so aren’t totally clear, and because we have few interventions by which a government can radically change dietary or exercise or lifestyle patterns at the population level, it falls on the individual to make dozens of choices each day in the hopes that they will be beneficial in the aggregate. But though some of us can make rational decisions to form better habits, most of us can’t.

Human motivation is a strange thing. The influence of others will never map cleanly onto the actual science of health, but a useful fiction, clear and compelling, can motivate action in a way that reams of dry information cannot. If podcasts and TikToks help sustain healthier lives in a world that militates against them, then influencers — even though there are real problems with relying on entrepreneurs for health advice — serve a role.

There are the obvious pitfalls. The whole enterprise of influencer health education floats on an ocean of dodgy supplements. Plenty of advice is nonsensical and some of it is dangerous. There are responsible and irresponsible ways to profit from the promise of health. And even the contingent argument in defense of influencers has a limit; at some point benign myopia bleeds into delusion.

“What I’m trying to do for you right now is Da Vinci Code you, put all the pieces together. Why is every screen blue-lit? That came from the CIA and MKUltra,” says Jack Kruse, midway through a more than two-hour harangue of powerlifter-turned-influencer Mark Bell and his podcast co-hosts. Kruse’s abstruse meanderings make it hard to understand exactly why he thinks what he thinks, while also giving him a veneer of genius and his followers a veneer of sophistication.

These ideas are of course too complex to explain in any more straightforward manner than Kruse does, but just listen long enough and you might glimpse the big picture. Also, so profound is the effect of adequate sunlight on the brain that it may be impossible to truly get what he’s saying until you’ve spent a few months soaking up solar energy. Then you too can join the ranks of the “Black Swan mitochondriacs,” who, he writes on his website,

are unique because they see and sense the same things as everyone else, but they are capable of thinking what no one else has thought about what they have observed. This is why their perspective OFTEN diverges from the crowds and paradigms.

In a Facebook post, he adds (sic on all these quotes):

To think like a Black Swan requires you to embrace makes you realize that nothing WORTHWHILE is ever easy. We embrace these challenges and what they entail. Sunlight protects and opens to superhighway nature built you between your heart and brain.

The free-associative, science-as-jazz style that Kruse employs quite effectively in his speech and somewhat less effectively in his writing is not about educating in any normal sense of the word. Kruse’s project is to suffuse the mundane with new meaning. It’s not just about moving your lifestyle in a better direction; it’s about joining the decentralized resistance. We dwell in a corrupt world shaped by nefarious forces, and a brave new ultraviolet elect must boldly forge a path through it toward a better future. He doesn’t just want your dollars or your attention, he wants to reform your mind and your soul.

Kruse is an extreme example. It’s easy to spot a charlatan when he claims to have revolutionary insights into every human disease and also into evolutionary biology and also physics and also politics and also economics. But, though they may be less fanciful than a bespoke, mystical techno-anarchism, the projects of most influencers promise at least an individual utopia. Stack enough protocols atop each other and they will amount to a healthier life. Hold your nose, bite that liver, and watch your bank account grow even faster than your biceps. Work out hard enough and you will be spared the dependencies and indignities of old age.

In The True Believer, the philosopher and critic Eric Hoffer writes, “The quality of ideas seems to play a minor role in mass movement leadership. What counts is the arrogant gesture, the complete disregard of the opinion of others, the singlehanded defiance of the world.” The trouble is that the world we find ourselves in demands a bit of leadership, a bit of disregard for the opinions of others, and at least a bit of defiance. Still, a lesser prophet is one thing, and a would-be Messiah something else. Exercise care.

Keep reading our Winter 2025 issue

How the System Works • Make Suburbs Weird • The New Control Society • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?