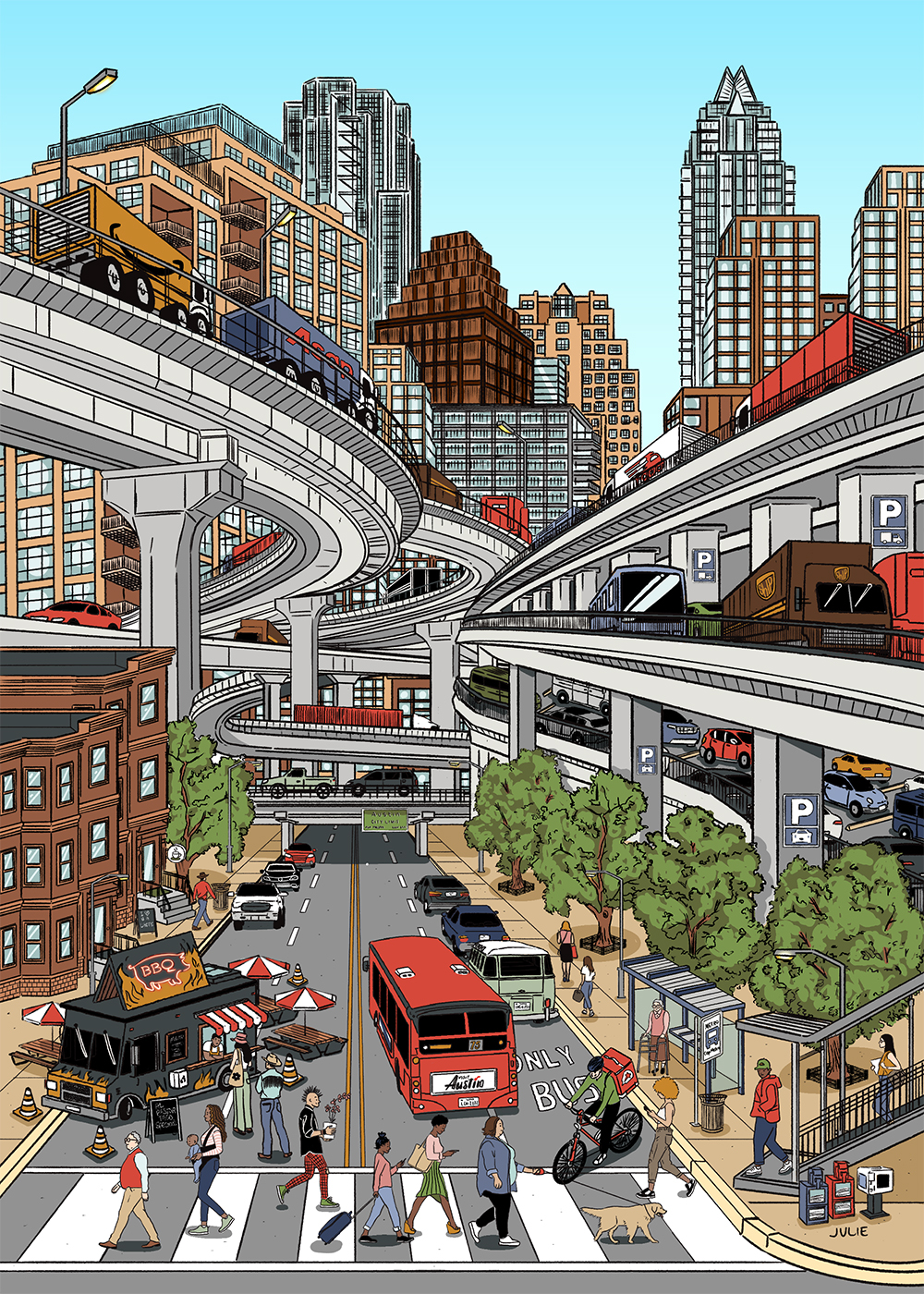

Interstate 35 through Austin, Texas, is the most congested stretch of road in the fastest-growing city in one of the sprawliest states in the country.

Yet the Texas Department of Transportation’s plan to expand the highway starting this year faces opposition from a well-organized contingent of local activists. They argue that the expansion will fail to reduce congestion because it will only coax more drivers onto the road — an effect known in urban and transportation policy circles as “induced demand.”

The opponents of the expansion are mostly a speck of blue in a red state, where the vast majority of people are not conflicted about car-dependent lifestyles. And the activists have failed to stop the project, pending a last-ditch lawsuit. But they are part of a nationwide movement aiming to limit highway construction that has gained strength in recent years.

The controversy extends well beyond the question of whether highway expansion reduces congestion — it’s part of a low-level culture war over how cities should form and grow. On one side are urbanists who favor denser cities, public transportation, and walkable neighborhoods. On the other side are — well, on these matters there is not really another side. It’s sort of a one-sided war. No one actively opposes walkable neighborhoods or reliable transit. No one thinks it would be terrible if the United States had beautiful, charming cities like Venice.

But there is a war over priorities. Urbanists see their vision as fundamentally at odds with highway expansion, which they consider a threat to safety, tranquility, and the health of the globe. Meanwhile, the proponents of the I-35 expansion are generally business and government leaders who see expanding highways as a straightforward necessity for accommodating traffic in a growing city. They, too, appreciate walkability and beauty in theory, but do not see cities like Austin becoming Venice anytime soon, and thus fear that the invocation of those concepts is little more than an excuse for stopping needed highway expansions.

They tend to be “people in business who are excited about regional growth,” said Paige Ellis, a former mayor pro tempore of Austin, who successfully advanced a city council resolution calling for a pause to construction on the upcoming expansion project. They are people who want to see development and construction, Ellis told me in a video chat, and see opposition to highway expansion as the work of the “Austin hippie who wants cleaner air.”

The reason that congestion receives so much attention in this war is because it is where the model of car-oriented development is vulnerable. No one likes sitting in traffic.

The tools of economic theory and econometrics suggest that, to the narrow question of whether the addition of lanes will ease rush-hour congestion on a given freeway, the answer is: probably not. But there are bigger questions to be asked about how a highway fits into the vision for a city.

Interstate 35, stretching from Laredo, Texas, at the Mexican border to Duluth, Minnesota, on Lake Superior is critical for commerce. Within Texas, it runs through San Antonio, Austin, and the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, meaning that nearly half of the state’s population lives nearby. It’s one of the fastest-growing areas in the country.

In Austin, the interstate runs directly through the city center along the path of what used to be East Avenue, the dividing line between black East Austin and the rest of the city under segregation. It has marked a socioeconomic divide ever since.

The short section of I-35 that runs through the heart of downtown carries almost 150,000 vehicles a day, and the 8-mile portion that stretches through the entire city accounts for 8 million hours of delay annually, according to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT, pronounced “tex-dot”) projects that traffic on that downtown section of road will swell to about 200,000 vehicles per day by 2030, adding unimaginably to existing traffic.

In August 2023, TxDOT issued a record of decision to proceed with an expansion of the highway, an action that came after years of planning and notice and public comment, and following an improvement in the state’s transportation budget, thanks in part to infusions granted by Congress in 2021.

The current plan, estimated to cost $4.5 billion over eight to ten years of construction starting later this year, is to lower the roadway to make room for cross streets, remove existing upper decks, and add two high-occupancy vehicle lanes in each direction. The overall footprint of the highway would increase slightly, displacing a few hundred existing properties.

The purpose of the expansion, according to TxDOT, is to accommodate future demand for travel along the highway — a concept that is highly contested, as we will see. The department projects that the expansion will reduce peak-hour travel times on the main lanes by 57 percent and increase the number of people who can be moved along the highway by 150 percent, from 13,500 to 33,600 people per hour.

The first estimate is the one that is most hotly challenged. Rethink35 and Reconnect Austin, two groups that advocate against the expansion of I-35, argue that the phenomenon of induced demand means that TxDOT’s promises cannot be fulfilled. The argument is the centerpiece of much of their advocacy.

Reached for comment on the induced demand criticism, TxDOT did not respond directly to it, noting instead that the metro area population is expected to double by 2045, necessitating more capacity.

In 1962, the year I-35 was completed in Austin and just six years after President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, the economist Anthony Downs published an article in Traffic Quarterly proclaiming the Law of Peak-Hour Traffic Congestion: that rush-hour congestion inexorably rises to the level of a highway’s capacity.

The critical point is that, for as long as the new capacity offers time savings, it will draw in additional rush-hour drivers — from other roads, from other times of day, and from other modes of transportation, such as rail or biking. It will also draw in people who previously simply stayed home. More and more will opt for the highway until it becomes crowded again and congestion rises — to the point that the earlier time savings have vanished.

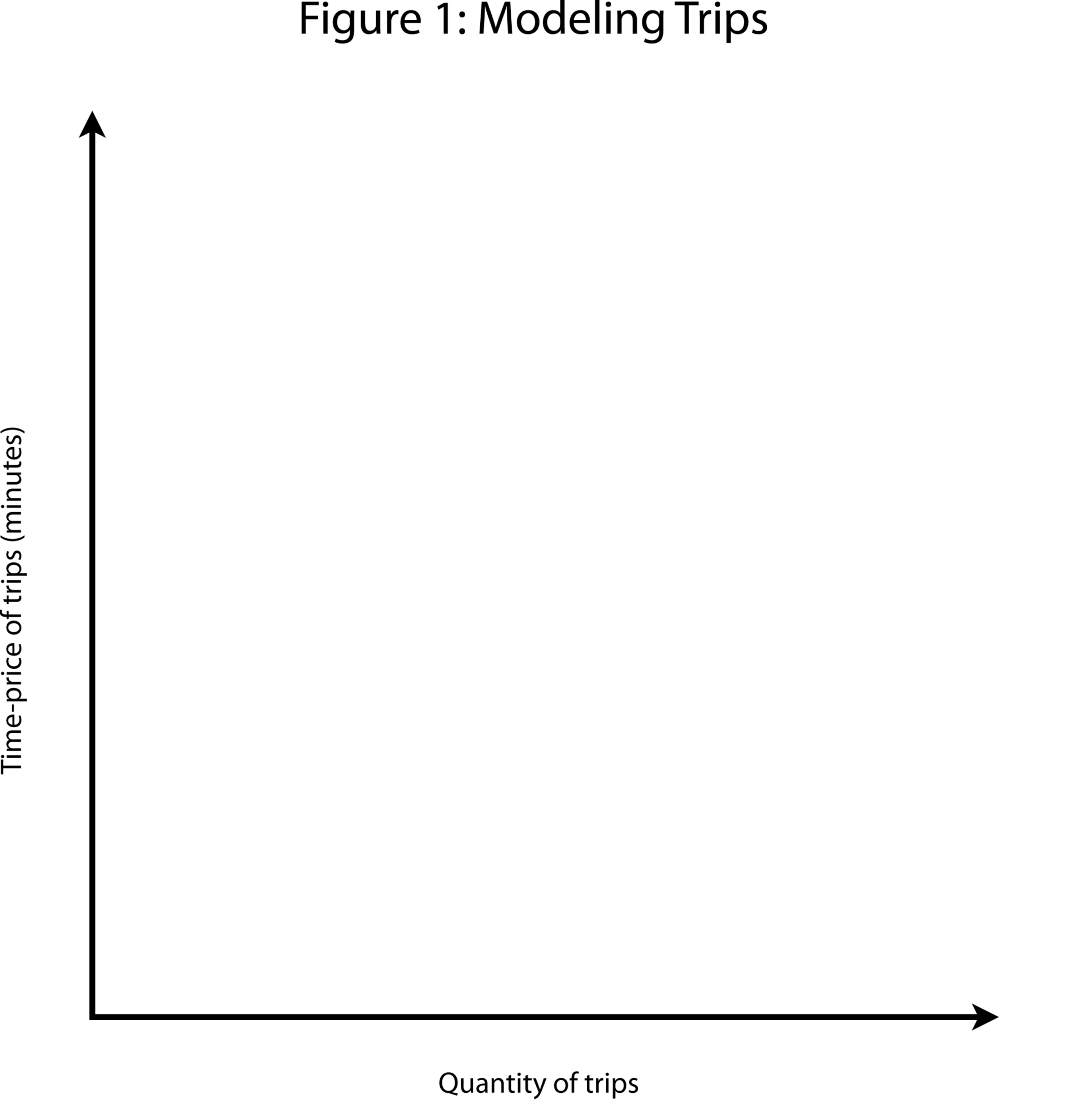

What Downs was describing would be familiar to economists as a movement along a demand curve. The concept is an example of the most basic tool in economics — the supply and demand model — providing a non-intuitive insight.

To emphasize: Without the tools of economics, it is very easy to get confused by shifts in demand versus movements along demand curves. But the distinction is critical to understanding the effects of adding lanes to highways.

Accordingly, it is worth the mental effort of walking through a simple supply and demand model of rush-hour trips along a highway to understand the logic. But readers who would rather skip the microeconomics can proceed past the charts to the next section.

First, create a chart that has the number of trips on the X axis and the “price” of each trip — which is the time it takes — on the Y axis:

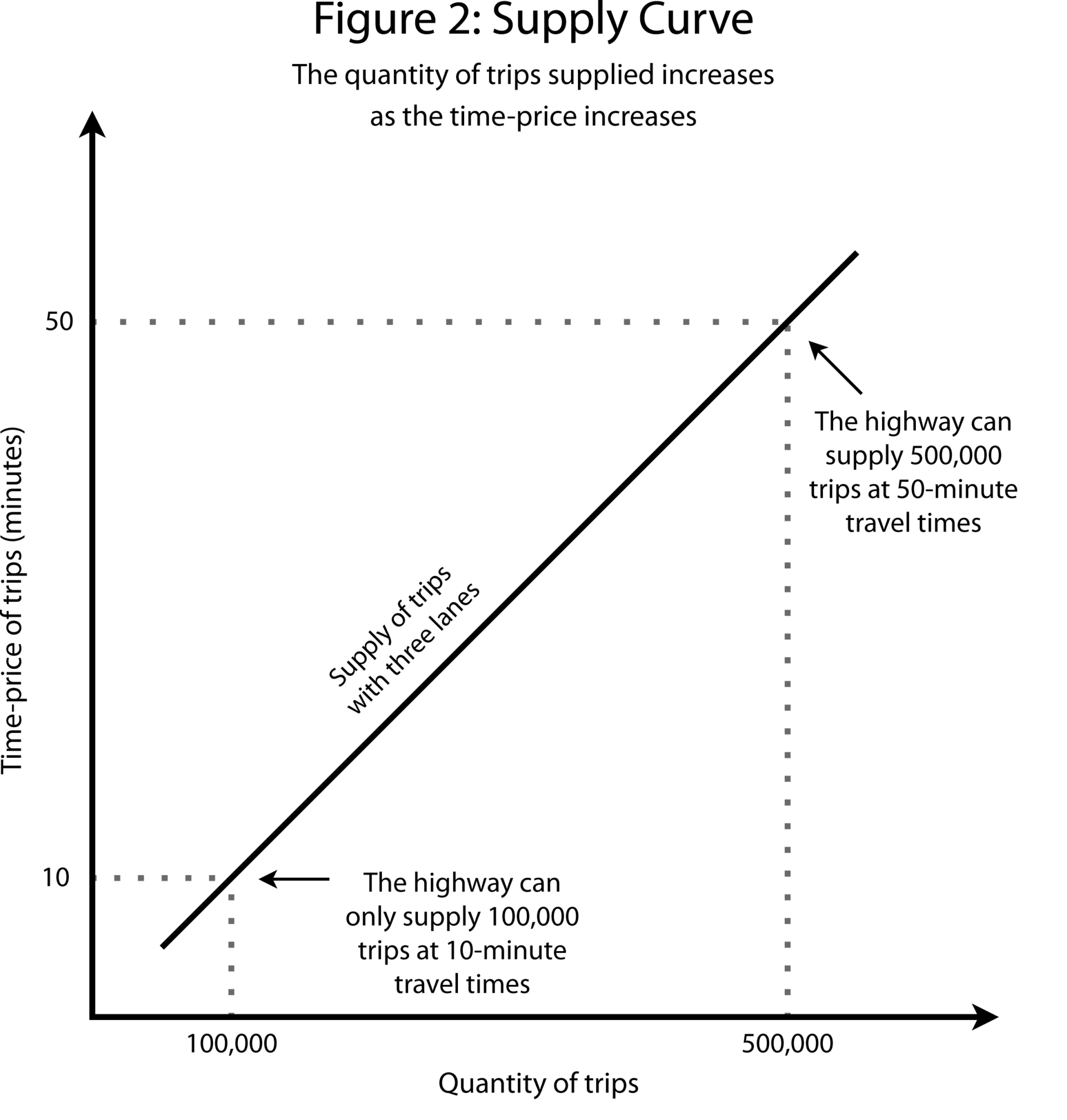

Now, illustrate “supply” — that is, the number of trips that a highway can accommodate. The highway can easily supply a small number of trips at low time-prices — if the road is empty, a driver can fly through the city, no problem. As the number of trips rises, though, congestion starts to mount, and trips take longer. Thus, the supply curve is upward-sloping: more trips supplied means higher time-prices.

Let’s draw a supply curve for a three-lane highway, using simple, hypothetical numbers (see Figure 2):

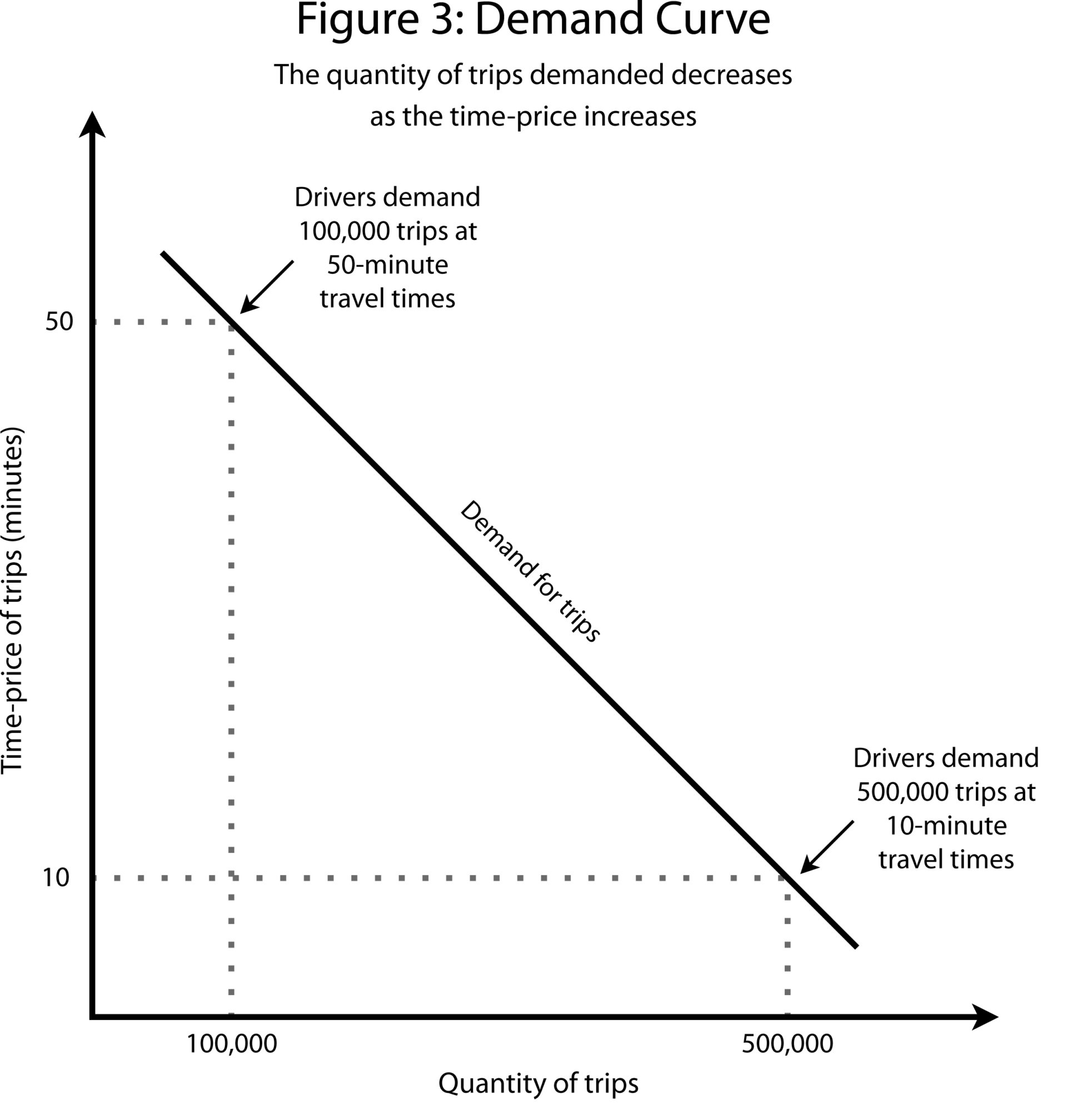

Now, let’s look at demand. A lot of people would be glad to drive downtown if they could fly down the highway in a matter of minutes. Fewer, though, are willing to brave traffic. In other words, higher time-prices mean fewer trips demanded: the demand curve is downward-sloping (see Figure 3):

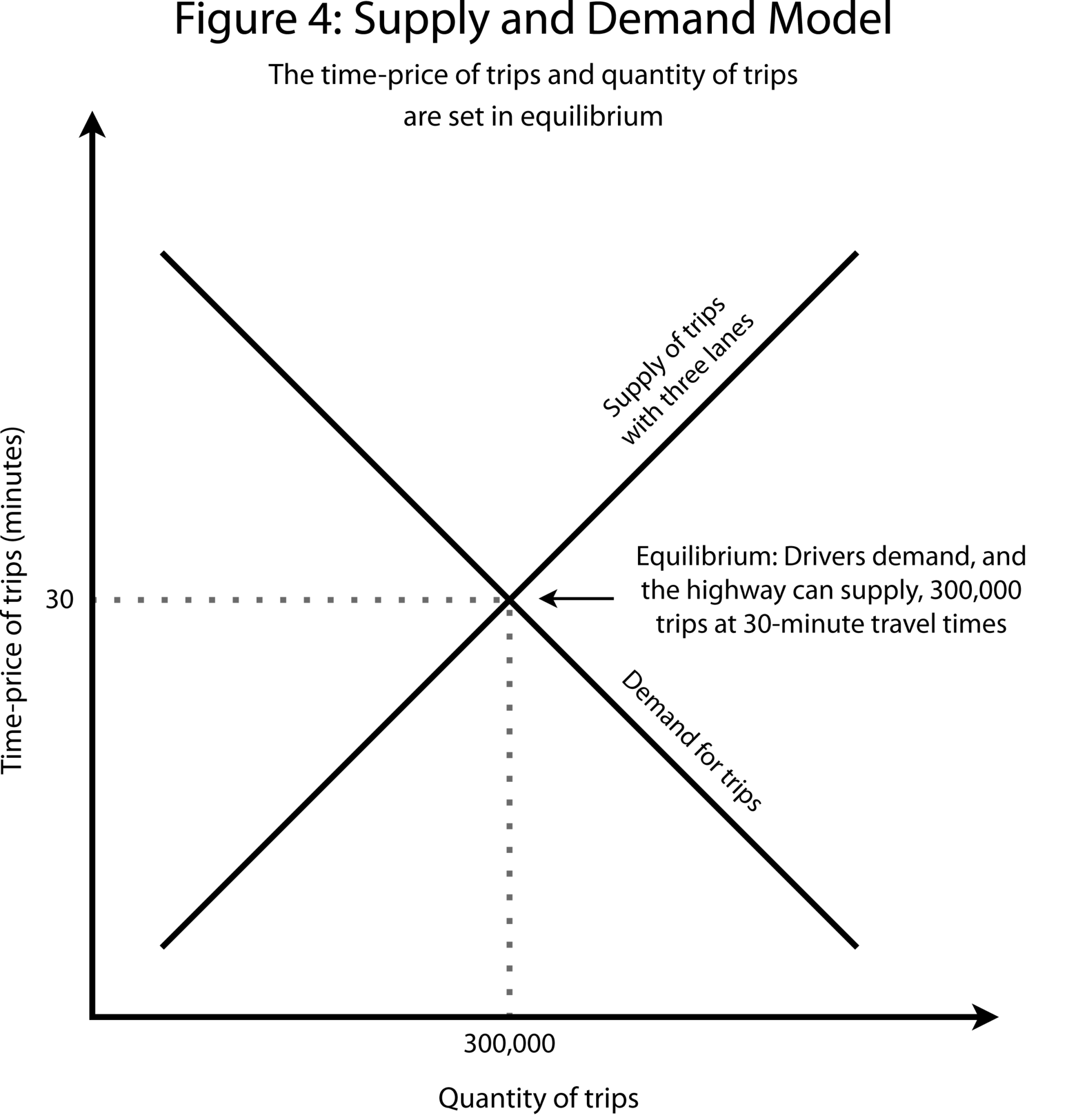

To complete the model, put supply and demand together (see Figure 4).

Based on our model, the time of travel has to be 30 minutes. If it were any lower, more trips would be demanded than the road could provide. If it were any higher, drivers would cut back until it fell. Thus, the equilibrium price is 30 minutes and the equilibrium quantity of trips is 300,000.

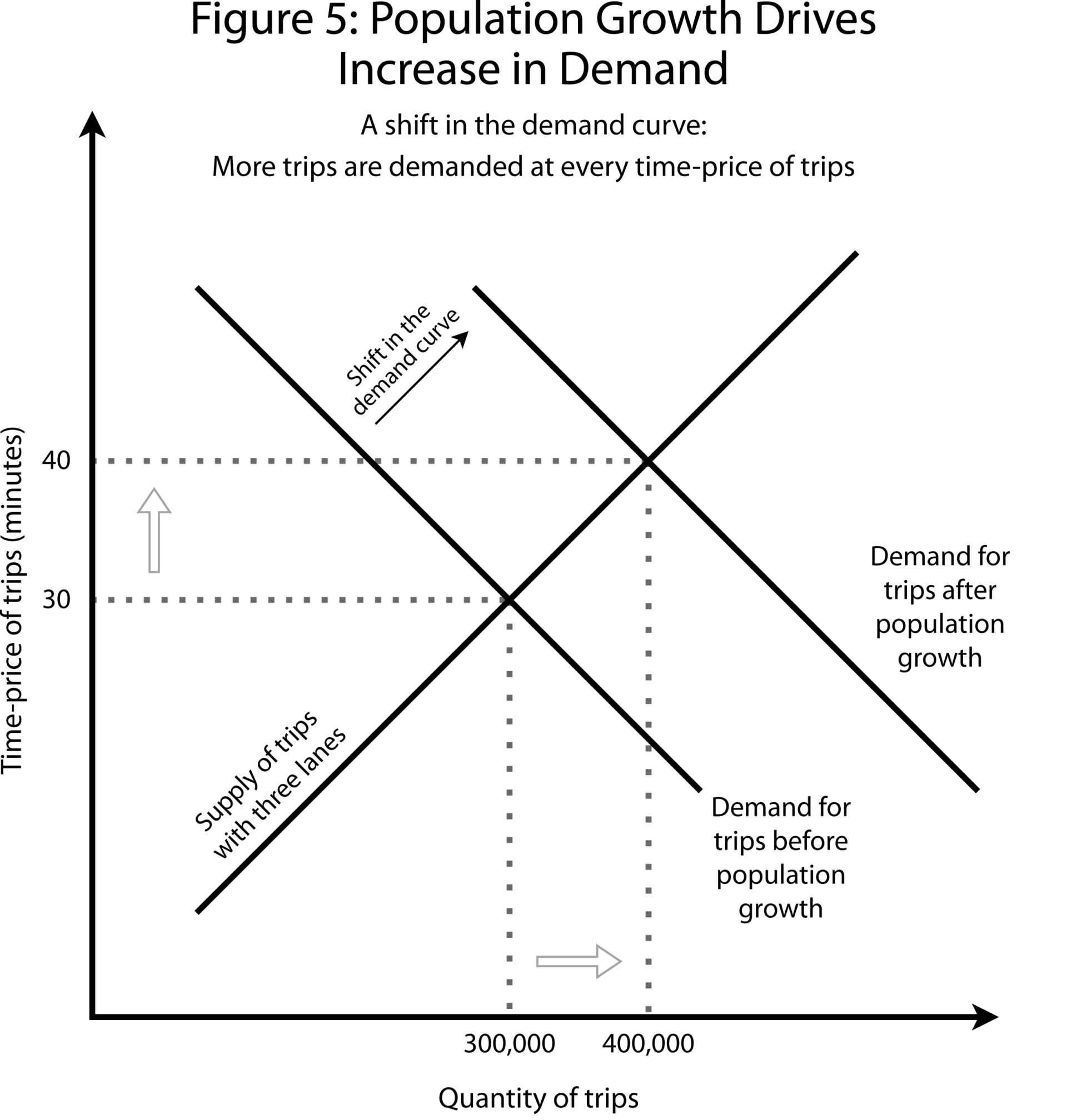

Let’s imagine a scenario where we see an increase in the quantity demanded for straightforward reasons. In this case, let’s imagine an exogenous increase in demand driven by a sudden population boom. In this case, for every possible time of travel there are more trips demanded, because there are far more drivers, of all different tolerances for traffic (see Figure 5).

This scenario is represented as a shift in the demand curve: more trips are demanded at every time-price. The net result is that congestion rises, and the number of trips rises.

But, crucially, the quantity of trips demanded can also rise without a shift in the demand curve. Instead, there can be movement along the existing demand curve, which is what happens when the supply changes.

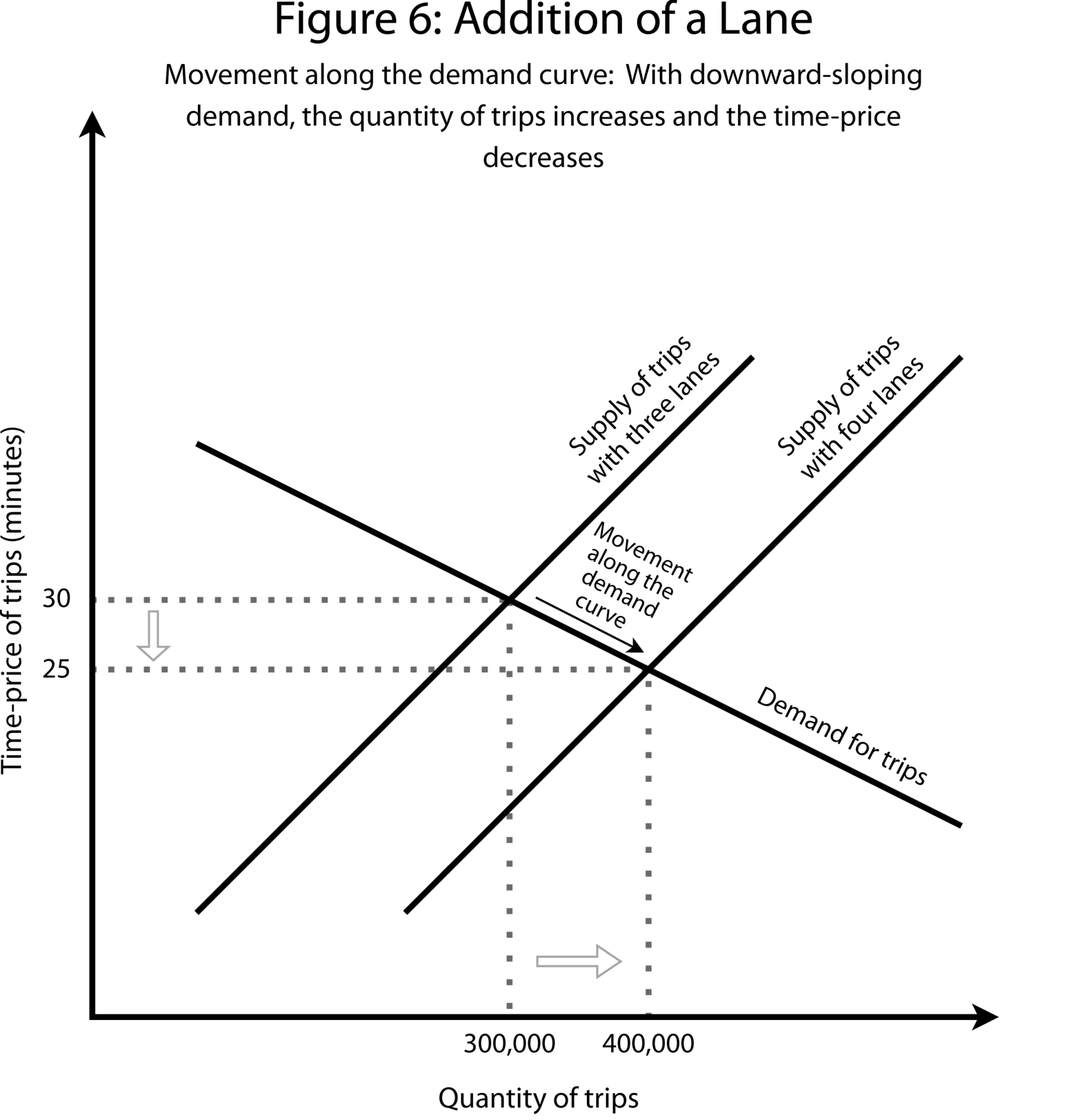

To see what this means, let’s think about what happens when the number of trips a highway can provide is expanded by adding a lane, while the number of trips demanded at every travel time stays the same. This is where we start to see the induced demand scenario (see Figure 6).

The addition of a lane can be illustrated by a shift of the supply curve to the right, meaning that for every trip time, the highway can supply more trips than before. In shifting the supply curve, we also move along the demand curve. The number of trips rises significantly, from 300,000 to 400,000 in our hypothetical example. But as the model shows, the addition of a lane, even though it adds 100,000 more drivers, still reduces the trip time, saving drivers 5 minutes.

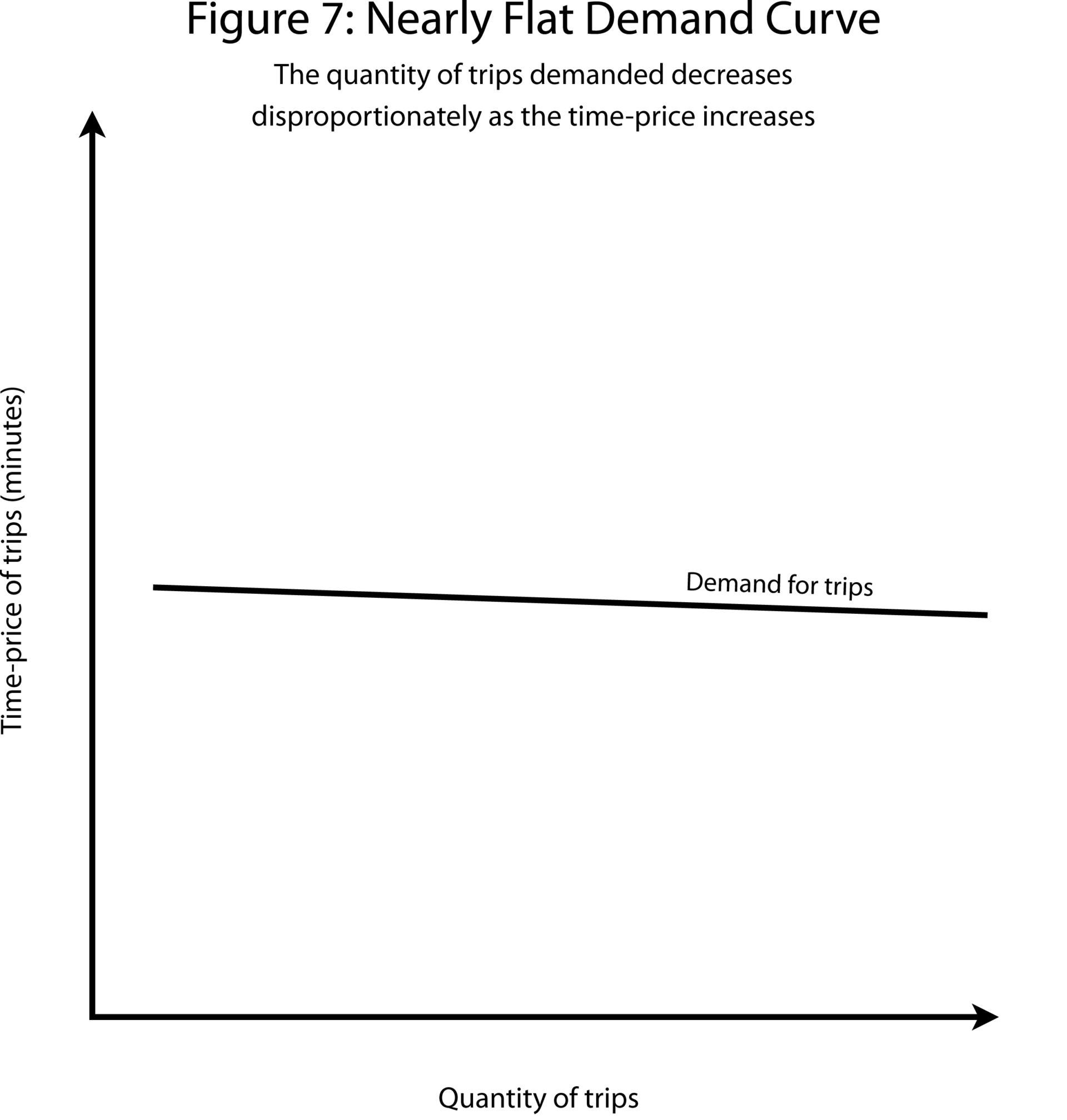

But what if demand responds differently to supply than we’ve modeled here? Remember that we’ve chosen the slope of the curve arbitrarily. Let’s assume instead that the demand curve is more flat than strongly downward-sloping (see Figure 7).

A flat demand curve illustrates what economists call “elastic” demand, which is when a small change in price entails a big change in the quantity demanded.

One way to describe elastic demand is that commuters are highly sensitive to commute times. If an improvement in highway traffic saves them a few minutes, they’re much more likely to drive. If, conversely, traffic gets worse, they’re highly likely to avoid it, whether by commuting early, taking a train, staying home, or moving out of the city altogether.

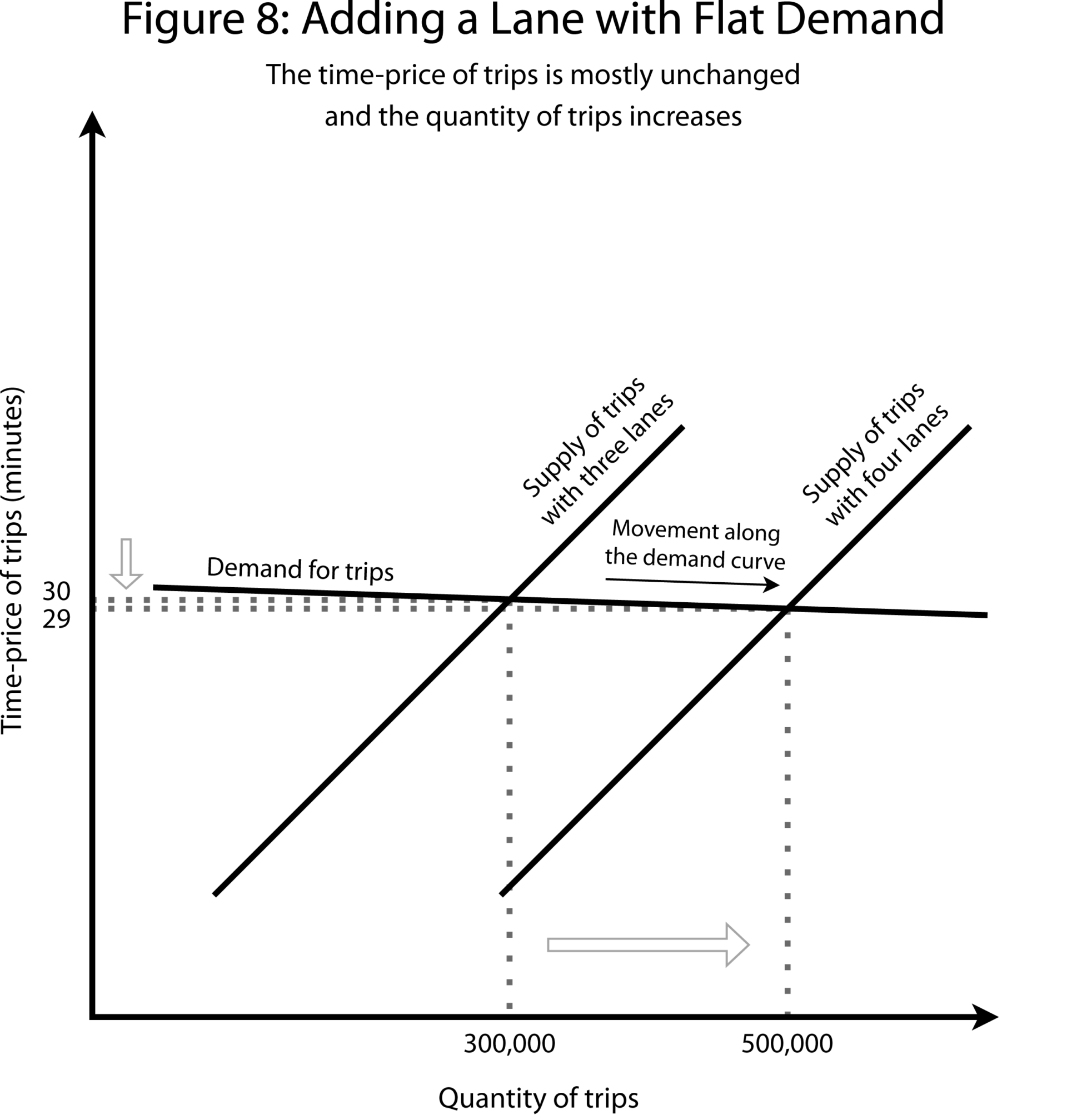

Next, let’s see what happens to our model when we add a lane to the highway and the demand curve is mostly flat (see Figure 8).

In this case, although the added lane accommodates 200,000 additional trips, the time-price dips negligibly, shaving only a minute off the commute. The added capacity did not significantly ease congestion. Or, to put this the other way around, the time savings of only a minute encouraged 200,000 more drivers to get on the road.

That is an illustration of “induced demand.” Adding a lane didn’t conjure up new desires for highway travel. Rather, it accommodated demand that was already there, at that time-price. In that sense, “induced demand” is a misnomer. Several experts interviewed for this story suggested the better term would be “latent demand,” a phrase that might more effectively express the idea that the increase in the number of trips is just what would be expected in a basic supply and demand model when a shift in supply (in the form of a new lane) leads to a movement along the demand curve for trips.

To sum up the scenario in another way, there was a pool of people for whom the call between driving downtown and all the alternatives was marginal. The addition of a lane tipped the scales in favor of driving, and they all got on the road. As they piled onto the freeway, congestion soon rose to where it was before — but, and this is a critical point that will come up later — the additional lane did accommodate more commuters.

So, in conceptual terms, the key factor for the strongest form of the phenomenon known as induced demand — in which congestion is virtually the same as before — is a demand curve that is essentially flat.

In determining the relationship between adding lanes and peak-hour congestion, what matters more than anything is the shape of the demand curve. It’s not the supply of highways, nor total demand, nor the size of the commuting population. It is whether demand is elastic, meaning that it is highly responsive to changes in the time the commute will take.

Whether that condition holds in real life is an empirical question.

The opponents of the I-35 expansion in Austin insist that past highway expansions demonstrate clearly that they don’t work to lessen traffic. “There are almost no examples of a beneficial highway expansion project,” Adam Greenfield, a co-founder of Rethink35, told me by phone.

Conversely, proponents say that there are in fact highway expansions that have lowered traffic — including around Texas and even in Austin.

The difficulty, of course, is that highway expansions often take place alongside other major changes to cities. In Austin’s case, the city has been undergoing tremendous growth and transformation. Accommodating traffic is a fast-moving target.

The challenge of distinguishing latent demand from shifts in the demand curve, such as those caused by rapid population growth, has doomed a host of studies to irrelevance in the years since the publication of Anthony Downs’s 1962 article.

In the past fifteen years, though, a branch of econometric literature has developed that is aimed at disentangling the causes of demand for highway travel. How much of the causation runs one way — the fact of more people needing to use the road leads authorities to build more capacity? And how much of the causation runs the other way — added capacity draws more people onto the road?

The seminal work in this line of research is a paper published in the American Economic Review in 2011, “The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from U.S. Cities,” by the economists Gilles Duranton, now at the University of Pennsylvania, and Matthew Turner, now at Brown. To tease apart the two directions of causation, the study employs what economists refer to as an “instrumental variable” approach.

How much of the demand for highway trips in an area is explained purely by how many highway lanes are available? We can’t answer this question by simply looking at cities that have added highway lanes and seeing how demand changed, because, as we’ve said, perhaps authorities added lanes because demand had already grown. Instead, we need to find some factor that meaningfully predicts how many highway lanes are available in an area today, but has no relationship with whether that area is growing or stagnating today. If we had that factor, we could find out whether the real world looks more like Figure 6 or Figure 8. We could see what happens when the supply curve shifts along the demand curve, and thereby find out the actual shape of the demand curve. An instrumental variable is that kind of factor.

The authors of this paper used three instrumental variables to predict modern highway construction: routes of major expeditions of exploration between 1835 and 1850, the 1947 interstate highway plan, and 1898 railroad route kilometers.

The idea is that the factors that explain whether an area’s demand curve for highway trips has been shifting recently — such as job gains or population growth in a given city over the past few decades — could not possibly have influenced these instrumental variables, which were set decades or centuries ago. “The robber barons did not place rail tracks where they did because they expected the path they chose to be good commuting routes 150 years later,” Duranton explained in an email. Put another way, these long-ago decisions are still useful in predicting which cities today have lots of highways and which don’t, but they’re not useful in predicting that Houston today enjoys a booming energy business while Detroit is sagging under a manufacturing collapse. And this means that the robber barons left us a general picture of movement along the demand curve — of how varying the highway supply changes how many people get on the road.

Using data from multiple federal surveys, and controlling for other drivers of demand for travel — such as demographics, industrial decline, and urban amenities — the authors then assess the relationship between highway construction and vehicle-kilometers traveled. They find, essentially, that in U.S. metro areas, vehicle-kilometers traveled on interstate highways increase one-to-one with lane kilometers, and conclude that the results confirm Downs’s Law of Peak-Hour Traffic Congestion. In other words, any supply added is fully used up — which is another way of saying that demand is fully elastic.

In recent years, a range of other papers using similar methods of causal inference and examining a range of settings have similarly yielded the conclusion that highway construction does not ease congestion. A 2022 Journal of Economic Geography paper by economists at the University of Barcelona studied the 545 largest European cities and, using instrumental variables based on railroads and ancient roads, concluded that a 1 percent increase in highway-lane kilometers increases vehicle-kilometers traveled by 1.2 percent. A 2014 Journal of Urban Economics study by economists at Singapore Management University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong used Japanese road traffic census data and an instrumental variable based on the 1987 National Expressway Network Plan and found an elasticity of traffic-to-road capacity of at least one. A 2019 paper in Transport Policy used measures of state influence on key transportation committees in Congress as instrumental variables to find an elasticity of around one.

Other relatively recent analyses have found slightly lower responses, but the highest-quality and most relevant studies have found that the range of elasticities for highway expansion worldwide is between 0.77–1.34 in the long run, according to a 2022 round-up conducted by the National Center for Sustainable Transportation.

Before moving on, it is worth highlighting some limitations in applying this body of literature to the specific instance of I-35. One is that the research cited above is focused on vehicle-kilometers traveled on major highways, rather than throughout all the roads in metropolitan areas. Another is that none of the studies directly measure speeds.

It is possible that the “induced” traffic on the newly expanded highway could represent traffic lifted from local streets, which could be beneficial. TxDOT Austin District Engineer Tucker Ferguson cited such considerations in an emailed statement criticizing the alternatives to expansion advanced by Rethink35. “Pushing traffic to the city grid on a regular basis would be catastrophic for the region. The city network is not designed to handle this kind of volume or speed,” he wrote.

Robert Poole, the director of transportation policy at the Reason Foundation who has been critical of highway expansion opponents, noted that residents may well benefit from commuting on an expanded highway during peak hours, even if it’s congested, if this allows them to avoid worse traffic on arterial roads. “These are perfectly normal human adaptations to changes in the quality — not just the quantity but the quality of what’s available to them,” he said in a phone conversation.

Duranton said that his 2011 paper indicates that there is no such substitution from arterials when freeways are expanded, but that other research he is undertaking shows that there is substitution from residential roads instead. Overall, the empirical evidence on such considerations is still developing.

To sum up, on the narrow question of whether expansions lessen congestion on freeways, the theory and most cutting-edge empirical studies suggest that the answer is no.

But that fact does not settle the debate about an expansion of any given highway. To see why, it’s helpful to look at a specific example often cited by both sides of the debate in Austin: the expansion of the Katy Freeway in Houston.

The Katy Freeway, the major east–west highway for the Houston region, is held by locals to be the widest in the world, following an expansion completed in 2008. Its total number of lanes rises to 26 at points, if including frontage roads, also known around Houston as “feeders.”

Today, the Katy Freeway is badly congested. The four miles east of downtown qualified as the seventh-most congested section of road in Texas in 2023, according to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, with two intersecting highways ranking above it. The morning commute along the 19 miles stretching west from downtown Houston averaged about 30 minutes in the early 2000s, before the expansion, according to reporting from the Houston Chronicle. Nowadays, Google Maps estimates that the same stretch in the morning takes 30 minutes to an hour.

Highway opponents argue that if building literally one of the biggest highways in the world doesn’t cut traffic, no highway expansion will. But there are also good reasons to consider the expansion a success.

David Schrank, a senior research scientist at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, noted in an email exchange that speeds on the freeway did fall immediately after the expansion. He provided data for the 26 miles stretching west from downtown Houston. For morning peak-hour inbound traffic, the average speed rose from 31 miles an hour in 2002 to 40 in 2009, shortly after the expansion was completed. Only later did the average speed drop again, down to 35.5 miles per hour in 2011. At that time, another major artery, Route 290, went under reconstruction, adding to traffic and complicating the analysis. Most critically, though, in Schrank’s view, the highway accommodated 35 percent more throughput during this time.

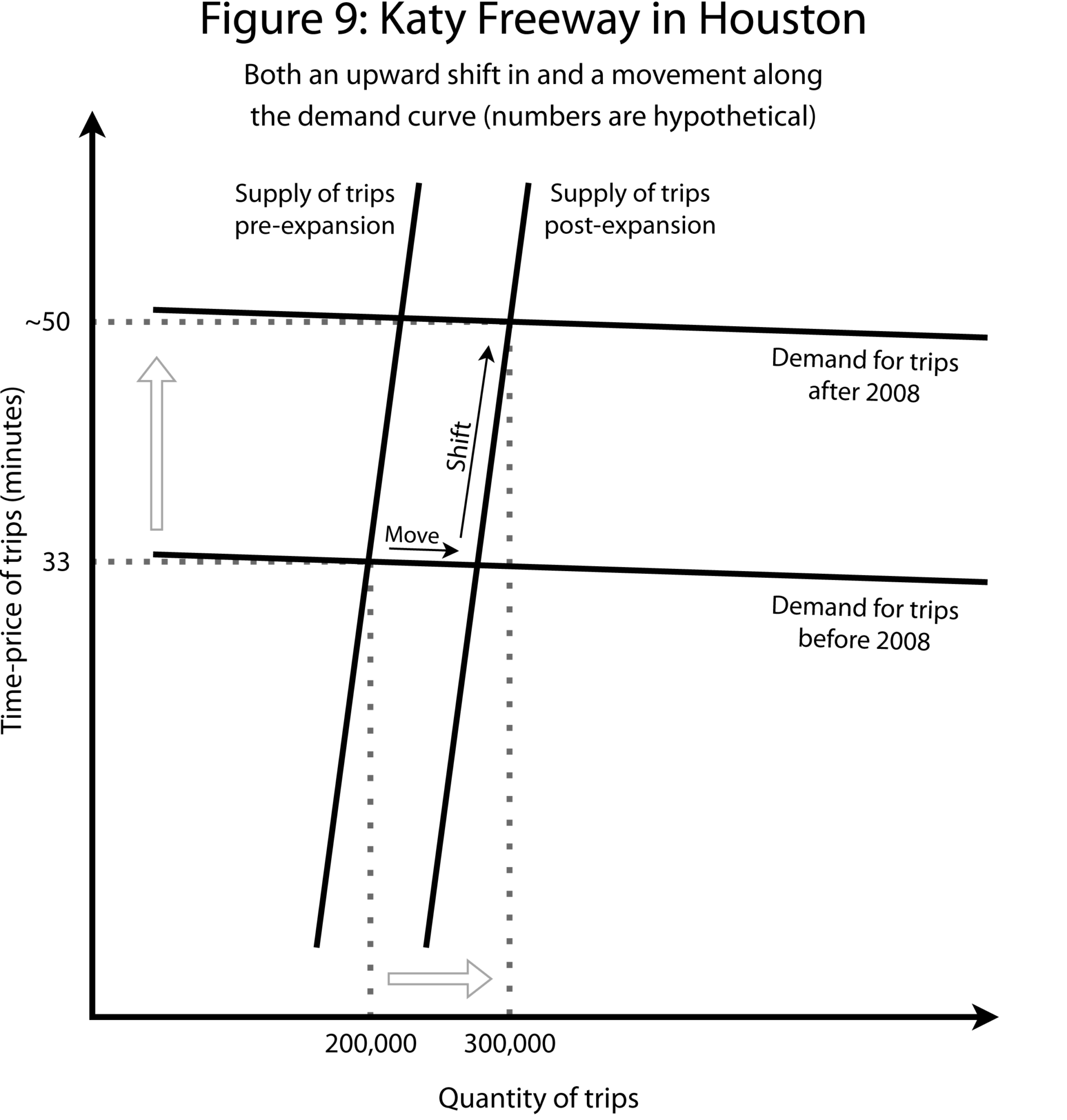

So, what happened on the Katy Freeway is consistent with a story in which authorities successfully expanded a highway to accommodate population growth, even if induced demand and then demand driven by further population growth later generated new congestion on the highway.

This outcome can also be illustrated using the supply and demand model: The supply of trips increased — a rightward shift in the supply curve. But demand rose as well, both because of population growth and induced demand — an upward shift in the demand curve as well as a movement along it (see Figure 9).

So the expansion of the Katy Freeway is not a clearcut example of induced demand alone, but it does illustrate the dynamic over time in the real world.

One important reason the Katy Freeway is choking with hundreds of thousands of additional travelers is that Houston is an urban success story. It has added 2.5 million people in the past two decades. Nationwide, only the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex has outstripped that growth, in absolute terms. Every year, people from all backgrounds — from pricey Los Angeles, cold Chicago, and indeed all over the world — pour into Houston, attracted by cheap housing and plentiful jobs.

Jobs are the key. Generally, the number of jobs within a radius of one-hour travel time — which means an average commute of around 30 minutes each way — delimits a labor market, and the labor market defines the city, the urban planner Alain Bertaud has argued.

Economists see larger labor markets as better in that they confer advantages through what are known as “agglomeration effects” — the benefits of bringing workers together. “The more destinations that an individual potential job seeker can reach in, say, 30 minutes throughout an area, the more economically productive that area becomes on aggregate,” said Robert Poole.

Why exactly productivity rises with the density and size of a labor market is a question that economists are still investigating. One factor is that a large labor market provides for the easy flow of ideas, as highlighted by the eminent urban economist Edward Glaeser. Living in Silicon Valley, for example, gives entrepreneurs a massive advantage. There, the odds are much higher than elsewhere that they might run into just the engineer they need for a project, or wrangle a last-minute face-to-face meeting with a venture capitalist.

Either way, the bottom line is that it is desirable to bring workers into a market. If the Katy Freeway expansion accommodated 35 percent more commutes per day, it was a success, in those terms. Better to be a thriving Houston, with choking traffic, than a Detroit, hollowing out with no one on the roads.

Urban economists and planners don’t see reducing congestion as the end goal of transportation policy. That might sound odd, since TxDOT’s premise for the I-35 highway expansion was that it would lessen congestion, and one of opponents’ chief criticisms is that it will fail to do that. But, in fact, urban growth and success have always entailed congestion.

One of Julius Caesar’s first acts as emperor, the historian Lewis Mumford noted in The City in History, was to ban wheeled vehicles from entering the center of Rome during the day, to limit congestion. Marcus Aurelius extended the edict to every city in the growing empire.

From neolithic times until today, the average commute has been about an hour a day, the Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti observed in 1994, a finding that has come to be known as Marchetti’s constant. Improvements in transportation haven’t changed the duration of commutes. Instead, they’ve increased the size of the area that constitutes the labor market.

So, for example, ancient Rome, built for walking, was about two miles across — about the length that could be traversed on foot in 30 minutes at a brisk walking pace.

The footprint of cities grew with the predominant transportation technology of the times — horses, streetcars, commuter rail, and then the car. The ability to drive at 60 miles an hour means that the commuting area can extend out 30 miles from the city center. Thus the greater metro area of Houston, the archetypal car-oriented city, extends from downtown all the way to Katy — a former rice-farming town almost exactly 30 miles out (though many commuters from Katy will need much more than 30 minutes to get downtown during peak hours).

Of course, in any given city, some people live right by their work and need only walk a few blocks each day. Others are supercommuters and come in from hours out — for instance, some people commute into New York City from Pennsylvania each day. But most commuters fall somewhere between these extremes. An average of half an hour each way appears to fit into the ebb and flow of human life. If that number drifts up, the situation will become intolerable enough that some people move closer, leave the city, or otherwise reorganize communal life.

Whether it’s waiting with others on carts and on foot to squeeze through the Porta Salaria, or being stuck in traffic miles out on I-35, congestion seems to be a marker of urban health.

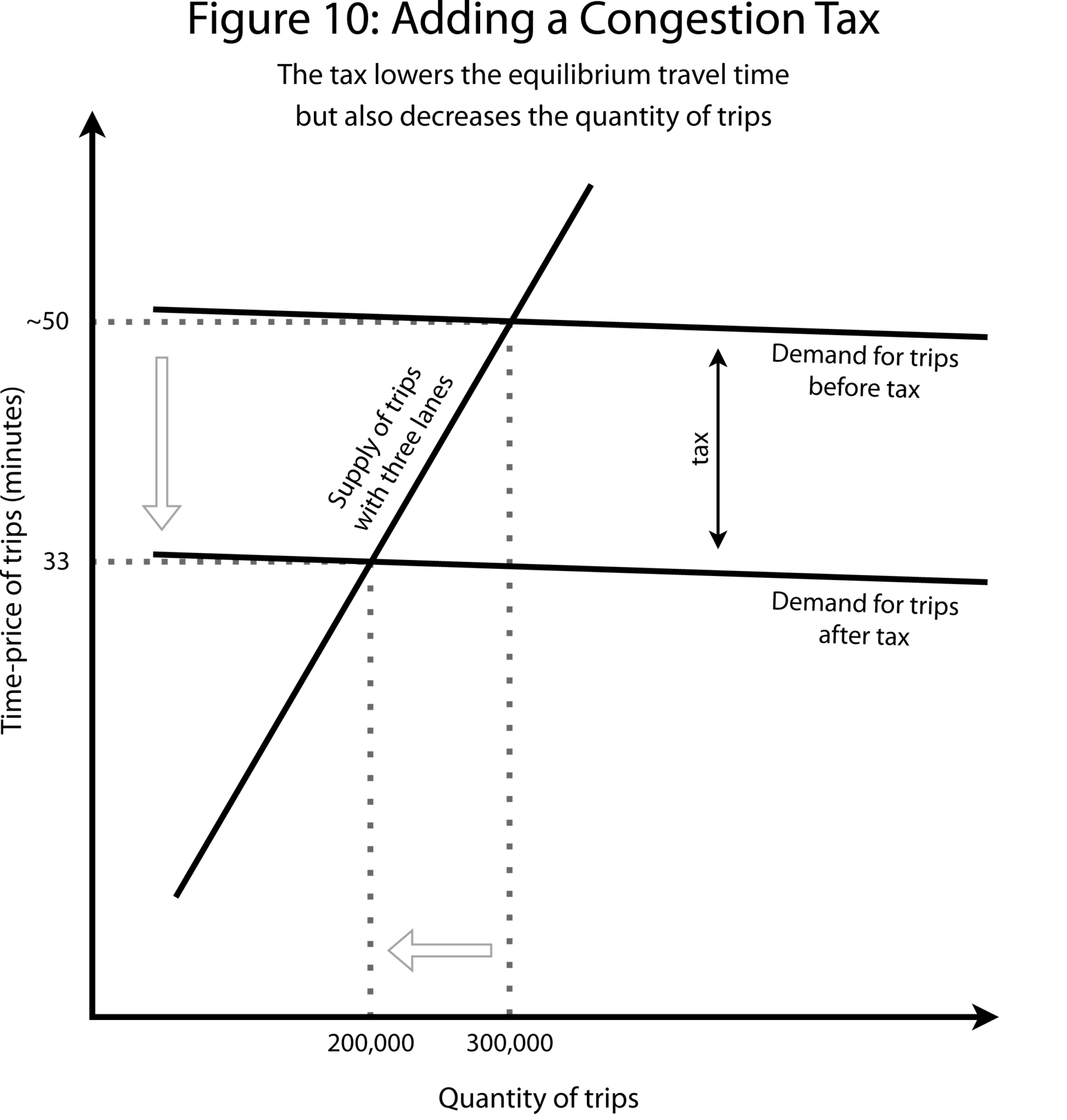

The point can also be seen the other way, by looking at the ramifications of lessening congestion through the preferred tool of economists — congestion pricing, commonly also called a congestion tax. This means raising the costs of tolls, public transit, parking, and so on. Let’s return to our supply and demand model and see what happens if you add a congestion tax (see Figure 10).

Note that the way the congestion tax works is by lowering the total number of trips — that is, via demand destruction. So the tax “works” in terms of increasing speeds on the highway. But it means that fewer people are on the roads, and, as noted, accommodating trips should be a fundamental goal for policy. (This analysis applies to the population level. The story is different for individuals, though. Several states have introduced forms of congestion pricing, such as “choice lanes” or “express lanes,” that give individual commuters the option to exchange money for shorter trips.)

In theory, congestion taxes could be paired with increased funding for transit. In Texas, though, congestion pricing is a no-go. In response to then-Governor Rick Perry’s vision for toll roads across the state, populist opposition rose up through ballot measures in 2014 and 2015 that sought to direct revenues toward funding for roads — but excluding toll roads.

Terri Hall, the executive director of the anti-toll group Texans Uniting for Reform & Freedom, said in a phone interview that congestion taxes don’t actually eliminate traffic, they simply displace it onto slower side roads, because people still need to make the trip somehow. “So where are those cars going to go? They’re going to find an alternate route, unless they’re going to get a new job,” she said.

So the case against congestion pricing, in the absence of other reforms, is the same as the case for expanding highways: Facilitating an absolute number of trips is worth it even if it entails more traffic. For all the attention given to congestion, then, its reduction is not the most important consideration for Austin, or any growing city. The more important question facing officials is what the urban layout will be and how people will traverse it.

It’s good that Austin is a booming city and that it has to plan for accommodating hundreds of thousands of additional commutes in the years ahead. The question is how those commutes will take place.

One possibility, the default, is the Houston model of greater urban sprawl facilitated by the expansion of highways to allow people to commute downtown.

The alternative involves a reliance on other modes of transportation — transit, biking, and walking — coupled with greater urban infill. A realistic model for Austin cited by multiple highway opponents is that of Seattle, an economically healthy city that in recent years has built out transit while pursuing greater density.

To help think through the tradeoffs involved in either model, economists and urban planners favor the paradigm of “accessibility,” which is defined as the ability to reach desired destinations. Accessibility is distinct from “mobility,” which is generally defined as the ability to travel across distance. Whereas mobility would be quantified as the speeds on roads, accessibility would be quantified as the number of desired destinations — generally defined as job sites — reachable within given time thresholds.

Viewing the debates over highway expansions through the lens of accessibility clarifies matters, and illuminates what goals the two sides share and where there are real disagreements that can be resolved only through the democratic process.

“Instead of asking the question of impact on highway level of service (a metric of congestion), one would plan and evaluate outcomes in terms of the ability of drivers to reach destinations,” Jonathan Levine, a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan, said in an email. “Accessibility — the ability to reach valued destinations — depends on mobility (basically, speed), and proximity.”

So accessibility has two parts of equal importance. The first part is mobility — the ease of getting around, whether it be by car, transit, bike, or foot. The second part, which is often ignored, is proximity — of relatives, friends, churches, parks, stores, restaurants, cafés, theaters, and, most importantly, jobs.

Ancient Rome was accessible because it was extremely dense. A realistic estimate of the population of the imperial city is roughly 450,000. Given that the city within the imperial walls had an area of just 14 square kilometers, that gives a density of over 32,000 people per square kilometer — greater even than that of modern Manhattan. Taking the most expansive definition of the city of Rome, to include 1 million residents spread out well into the hinterlands, an area of roughly 2,500 square kilometers, Rome’s density was 400 per square kilometer.

Compare that to an American urban area of similar population today. Tulsa, Oklahoma, and its surrounding metro area has roughly 1 million residents spread out over some 16,000 square kilometers, for a density of about 60 per square kilometer. Compared to ancient Rome, Tulsa has high mobility and low density.

Critically, accessibility is not determined by the number of roads or the speed of travel. Take, for example, New York City. New York is one of the most congested cities in America, yet it ranks at the very top of the list for accessibility, according to the University of Minnesota’s Accessibility Observatory, which measures the total number of jobs reachable in given time thresholds using federal jobs data and travel data from the GPS firm TomTom. To be clear — that is accessibility of jobs by car. It does not even take into account that New York City, uniquely among American cities, has a transit system used daily by millions and also a high proportion of people who commute on foot.

Or consider a comparison between the Philadelphia and Houston metro regions, which are similar in population size and density. Houston enjoys a speed advantage over Philadelphia. But because Philadelphia is denser, it has greater accessibility, according to a 2012 study by Jonathan Levine and others in the Journal of the American Planning Association.

Density, then, is the frequently overlooked factor in accessibility.

Viewing the case of Austin through the perspective of accessibility means taking the city’s land-use policies into account. Austin faces two options for maintaining or increasing accessibility, as described by Luis Osta Lugo, a board member of AURA, an Austin urbanist group. The first option is ever-increasing sprawl, facilitated by highway expansion. The second option is urban infill.

“You either need the highways necessary to subsidize sprawl outward into the Hill Country, where you see entire hills being paved over, to make way for the people that Austin didn’t allow into the city,” he said in a video interview. “Or, we build duplexes, and triplexes, and quadplexes and apartments and walk-ups, and any option in between there.”

Over the past several decades, much of the growth in the Austin metro area has been in suburbs 15 miles out, such as Buda, or near the 30-mile limit implied by Marchetti’s constant, such as Georgetown to the north, the fastest-growing city in the U.S. In the eyes of local urbanists, growth is being pushed out that far because Austin land-use regulations prevent construction of denser housing closer to the center of the city.

Most significantly, Austin’s zoning code — first implemented in the 1928 city plan partly to effect racial segregation by indirect means — has traditionally designated most residential land in the city to single-family housing. Single-family zoning strictly limits density. In Austin’s code, it means that residential lots have had a minimum size of 5,750 square feet, with additional height restrictions and setback requirements on buildings.

But other regulations limit density as well. Compatibility requirements, for instance, limit the construction of taller buildings, such as apartment buildings, near single-family houses. Building codes, too, make it harder to construct multi-family housing, by adding requirements such as multiple points of egress and thus stairways.

Altogether, Austin land-use restrictions have historically ruled out density — not just Hong Kong–style extreme urban density, but also what urbanists call the “missing middle”: duplexes, triplexes, garden-style apartments, and medium-sized apartment buildings. The absence of such construction in Austin has resulted in some jarring juxtapositions, with single-family houses just hundreds of feet away across I-35 from skyscrapers in the central business district.

With supply constrained and demand high, housing prices have skyrocketed in the Austin area. Home prices are up nearly 250 percent in the past two decades, according to the Federal Housing Finance Agency. Median rent for a two-bedroom apartment rose nearly 100 percent during the same period, Department of Housing and Urban Development data show.

What does all this mean for someone looking to move to the Austin area?

On the one hand, housing near the city center is going to be out of reach for those with modest incomes. The median price is $630,000, according to Realtor.com. To purchase a house at that price, at today’s mortgage rates and with a 20 percent down payment, an annual income of more than $150,000 would be required to avoid being considered burdened.

On the other hand, choosing a more affordable exurb — such as Buda, with a median listing price of $410,000, also means braving a commute. In Buda’s case, that would mean a commute of 30 minutes to an hour north along I-35 to get to downtown Austin.

The set of choices facing home-seekers is encapsulated in the real estate maxim “drive ‘til you qualify.” Most people have no choice but to head out further from the city along one of the major highways until they find a house priced below the largest mortgage for which they can qualify.

Terri Hall of the Texans Uniting for Reform & Freedom group faced this exact set of choices. She and her husband, then small business owners raising a large home-schooling family, were living in Spring Branch, between San Antonio and Austin, when she began getting involved in transportation policy and having to show up at the Capitol in Austin. That trip entailed braving horrendous traffic on I-35.

After enough days waking up at 4 a.m., she discussed relocating closer to the city with her husband. But prices in Austin were prohibitive. They instead bought a new place in Kerrville, even further out in the Hill Country but with a less congested route east into Austin.

The phrase “drive ‘til you qualify” describes existing accessibility in the greater Austin region, meaning that the overall level of accessibility is defined and limited by the state of the highways and the price of homes.

Of course, one way to improve accessibility would be to improve and expand the highways. That’s the track that Austin is on. It’s a model that is expected to bring in hundreds of thousands of newcomers in the next decade.

Critics, though, call that a coercive paradigm — putting the thumb on the scale in favor of sprawl by, on the one hand, limiting construction closer to the city center, and, on the other, subsidizing travel into the exurbs via highways. Given that state and federal governments help pay for highways out of general revenues, they argue, policy is not neutral with respect to the urban form, but in fact favors a pro-sprawl model.

Luis Osta Lugo said that his own experience shaped his advocacy. His family gained economic opportunity by migrating from Venezuela to Houston. Eventually they could afford a house — but only out in Katy. He benefited directly from the Katy Freeway, as it meant his family could live in Katy and commute into Houston. But the model of pushing upwardly mobile families further and further out along highways, he said, is “fundamentally unsustainable.”

Part of the logic is that, past a certain point, road construction can hurt accessibility. The tradeoff was quantified in a recent working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research that made use of modern travel-planning data, like that provided by Google Maps. The research found that a 10 percent increase in the area that is reachable by car in a given commute is associated with a 1.4 percent decrease in the share of green space — and that facilitating travel by car is associated, in the United States, with more pollution, worse health, and less favorable land use.

To be clear, compared to European cities, it’s much easier to get around U.S. cities, thanks to extensive road systems. But there are fewer attractions to get around to — and the more roads are built, the more true that becomes. Eventually, long car rides are necessary just to get past the roads and parking lots built to accommodate other car rides.

Urbanists argue that alternative modes of transportation don’t have this problem: they often don’t make a given destination unattractive — they can even improve it. A train improves the value and perceived amenities of the neighborhood around it, Osta Lugo said. Nor does transit contribute to congestion in the same way. In general, the induced-demand literature suggests that adding rail or subway transit reduces congestion by shifting the highway demand curve down, meaning that at every highway travel time there are fewer people demanding trips, although that’s not true for transit in the form of buses or other vehicles that share the road with cars.

Transit is also thought to enjoy returns to scale in a way that driving is not. The more people that use a light rail or subway system, in theory, the more routes can be added, as well as more trains, reducing the time between trains, up to a point.

Similarly, foot traffic is generally good for a neighborhood. Having people walking by on the street opens possibilities for retail, cafés, restaurants, and attractions.

Train and foot traffic are also seen by proponents as less costly in environmental and safety terms, less likely to kill people nearby by slamming into them or poisoning their air or water — or, for that matter, releasing gases that contribute to climate change. Such considerations are not incidental but fundamental to the case against highways.

At root, the complaints of I-35 critics are less about transportation than location. In their view, locations served by highways are less lovely, more polluted, and more dangerous than those that are not.

“We have not thought nearly enough about the costs we are imposing on the public treasury, on private individuals, and on public health the way we are doing it now,” said Tony Dutzik, a senior policy analyst with the Frontier Group, which has been critical of highway expansions.

Although the freeway-sprawl model is all that most Americans alive now have ever known, it was controversial from the start. The 1950s through the 1970s saw a number of revolts against adding new highways to urban centers. Some of the revolts succeeded, for example in Boston and New York, the latter involving famed urbanist Jane Jacobs.

The new anti-highway movement seeks to reclaim the legacy of those revolts, said Ben Crowther, the policy director for America Walks, a group that advocates for walkable communities. The movement’s immediate goal is to ensure that any new construction doesn’t expand the footprint of existing highways, he said in a phone conversation. The ideal is “building something else rather than the highway that supports community access and community interest.”

Crowther also helps lead the Freeway Fighters Network, a growing coalition of groups nationwide that has met since 2021 to track highway expansions across the country and organize opposition. In 2023, the group held its first in-person summit and put out a platform calling for a moratorium on highway expansions.

The other half of the equation is reforming land-use policy at the local level. In Austin, zoning reform proponents have started to see success, after years of struggling to gain traction. Most notably, minimum parking requirements for new developments were abolished by the city council in November. That single change will “help pave the way for car-lite and car-free developments,” Addie Walker, a volunteer for Reconnect Austin, said in a video conversation.

The city council has moved in recent months, too, to lift minimum lot size requirements and allow multiple units in areas currently zoned for single-family.

The local and national opponents of the I-35 expansion see their goals as far bigger than limiting highways. “This is not just about opposing something bad,” said Adam Greenfield. “We are potentially on the verge of an incredible new era of public transportation and restoring cities from the damage freeways caused.”

Of course, Austin will never be Venice. In general, cities vary dramatically in terms of road systems, density, and much more. Any attempt to impose a top-down vision of an idealized city would go nowhere.

As an example of what is possible, though, highway opponents point to Seattle as an alternative to the sprawl model. Seattle is no accessibility miracle, but its trajectory looks promising from an urbanist point of view. Over the past few decades, Seattle has approved the creation of a regional transit system and expanded light rail and bus transit. The city now claims that 70 percent of residents have access to transit within a ten-minute walk.

At the same time, Seattle has gotten considerably denser. In recent years, it has in fact outstripped Austin and other Sunbelt cities to claim the crown of fastest-growing big city. Seattle’s land-use policies are still restrictive. But, last year, the state passed major reforms meant to encourage density, including through missing-middle housing, and the city changed laws to encourage more units downtown. Seattle has succeeded in lowering the share of workers who commute to work alone by car from 35 percent in 2009 to 21 percent in 2022, according to the Frontier Group. Per capita vehicle-miles traveled have fallen substantially, too.

Becoming more like Seattle, let alone becoming a walkers’ paradise, is a tall task for Austin. Paige Ellis, the former mayor pro tem, said the city was ten to twenty years behind on the necessary infrastructure.

The alternative I-35 plan put forward by Reconnect Austin, and rejected by TxDOT, represented an effort to take a step in that direction. It would have moved the freeway underground, created an urban boulevard above it, added transit, and permanently shifted freight traffic out toward State Highway 130, which runs parallel to I-35 outside the city but is tolled. By doing so, the group argued, Austin would at once see higher throughput and greater density — in other words, improvements in both factors of accessibility: mobility and proximity. And it would become a more attractive downtown.

Proponents of the I-35 expansion, too, argue that it will improve accessibility. First of all, of course, it will allow more people to go in and out of the city each day. Furthermore, the new HOV lanes will encourage the use of bus transit. Also, the expansion will include the construction of boulevard-style segments, lower speeds on frontage roads, and 16 miles of new bike and pedestrian paths — all changes requested during public consultation. “It’s not an expansion project — it’s a project that improves not just mobility but so many other community values,” Jeremy Martin, CEO of the Austin Chamber of Commerce, said in a phone conversation.

Furthermore, the city council succeeded in winning federal funding to implement a “cap and stitch” design — capping, or covering, the highway at some points to create plazas, and stitching it with widened bridges at other points. That vision is likely to greatly increase east–west car, bike, and foot traffic across the highway, meaning that accessibility would be better than it is now. And in the future, Robert Poole of the Reason Foundation argued by phone, the growth of electric vehicles and the advent of autonomous vehicles might mean that highways impose fewer environmental costs on the area than they do now.

Altogether, then, it can be argued that the expansion is an improvement in accessibility over the status quo, even if it is not the rejection of the sprawl model that critics want to see.

The question is who decides between the available tradeoffs — whether Austin will become more like Seattle or more like Houston.

Right now, arguably, no one decides. Existing processes favor sprawl by default, argued Jay Blazek Crossley, executive director of Farm&City, a nonprofit organization that has opposed highway expansions in Texas. Sprawl, Crossley said in a phone conversation, is the default in TxDOT’s modeling, which assumes that people will continue to develop more and more remote areas, despite what is likely to be absolutely debilitating traffic to the city. Sprawl is also the default in regional-growth forecasts, in that they assume that empty farmland will be developed and served by new highway capacity but that existing urban areas will not — for instance, grocery stores with huge parking lots will not be converted to apartments. “The model assumes the roadway network to facilitate that sprawl will be in place,” he said.

In fact, some highway critics, in a lexical twist that has generated additional confusion surrounding the topic of transportation policy, have taken to referring to this dynamic as “induced demand” — the same phrase used to convey the related but separate meaning we saw earlier. “Highway expansion allows and encourages development to occur farther away from city centers and in more sprawling, auto-centric ways,” said Tony Dutzik in an email. “This is the argument behind induced demand — that highway expansion causes individuals and businesses to alter their behavior in ways that cause congestion to reemerge.” Induced demand, in this sense, is not about highway expansion encouraging you to get on the road in order to get to the city — it’s about highway expansion encouraging the city to get to you.

An additional complaint highway critics lodge is that the bureaucracy is de facto pro-sprawl, in that there are agencies empowered to build or improve highways, but not agencies empowered to do the same for cities. TxDOT has the funding to build highways, but not to build out other modes of transportation — let alone to address the other part of accessibility, for instance by permitting more housing in cities like Austin. There is a Texas Department of Transportation, but no Texas Department of Accessibility. “Land-regulation tends to be a municipal concern, and highway investment is largely state,” said Jonathan Levine. “We have no institutions that are pulling things together.”

In the absence of any such authority, a legitimate concern of highway expansion advocates is that the perfect urbanist dream will become the enemy of the suburbanite good. From their point of view, it is easy to imagine a situation in which the highway expansion fails, but so do the reformers’ hopes for rapid land-use reform and transit construction. In that scenario, not only will Austin fail to follow in the footsteps of Seattle, but it will also fail to become like Houston. Instead, it will just see gridlock and chaos.

Also, it’s important to note that the business and state interests that favor the expansion of I-35 do not oppose greater density, or investments in transit — far from it. As far as density is concerned, Jeremy Martin of the Austin Chamber of Commerce noted by phone that it is incumbent on city authorities, many of whom are skeptical of highway expansion, to change rules to permit more housing near downtown, a task at which they have so far had only marginal success.

And as for transit: last year, authorities unveiled plans to add new light rail to the city and expand bus rapid transit. The same business leaders that backed the I-35 expansion said that investing in transit too will be critical to accommodating the expected growth of the city. “You’ve got to be thinking multimodal…yes, you’re working on highways, but you also have to be thinking about pedestrians, and bicycles, and transit,” said Dewitt Peart, the CEO of the Downtown Austin Alliance, in a phone conversation.

Texans plan their daily commutes around what is feasible. And they rent or buy where it makes sense. There are plenty of people who would move further out and brave the traffic on an expanded I-35 if it meant a bigger and nicer house. On the other hand, many of the same people would move into a duplex near downtown and skip out on the commute altogether if that option were available and affordable.

For the most part, though, they will simply do their best given the set of constraints they find imposed on them. Texans, generally speaking, are not invested in the politics of transportation and urban planning.

Maybe they should be. Maybe they should be asked to be. In the coming years, Austin is going to add hundreds of thousands of residents. No one ever voted to have them shunted into exurbs in the Hill Country and proceed to clog up highways, but that is what is set to happen. If the people of Austin instead want them to settle in a pattern that more resembles Venice or even just Seattle, they’ll have to work quickly to reform transportation planning and land use policies to make it feasible. Otherwise, it will be left to TxDOT alone to get them where they’re going.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?