Sandwiched between two national parks on a winding mountain road, the Alpine village of Caldes, Italy, is so small as to barely warrant a label on most maps. With its thirteenth-century castle perched over a valley filled with apple orchards, nourished by the rushing waters of the river Noce, it seems an idyllic slice of rural Alpine life.

Places like Caldes have long provided a welcome refuge for Italians in the summertime, when oppressive heat makes the close quarters of the great cities to the south unbearable. Here they can enjoy the illusion of rugged wilderness, dotted by hotels and holiday homes. In the cool mountain air, tourists bike the great passes of the Dolomites, splash their way down white-water rivers like the Noce, and hike and jog on trails that wind among the narrow valleys.

It was to do exactly this that Andrea Papi left his home in Caldes in the evening of April 5, when the warm daylight of an early spring day yielded to the last of the winter nights. Stopping at an abandoned hut overlooking the valley, Papi took a short video, panning over the mountain valley, and posted it to his Instagram. The caption: “Peace ✌”

His peace was short-lived. That night, Papi was killed. When his body was found, it bore the signature marks of something reportedly not seen in Western Europe in modern times: a lethal bear attack.

The story of Andrea Papi may be a tragic anomaly in modern Italy, but it will not be the last like it. To employ the term current among today’s restoration ecologists, Italy is “rewilding” at a rapid rate. The centuries-long labor of Italian farmers, shepherds, hunters, and builders to tame the nature at their doorstep and keep predators at bay is now being undone. This is happening both deliberately, via government programs reintroducing large predators in ever-greater numbers, and unintentionally, through the long, slow abandonment of rural Italy, a process already underway for fifty years or more.

And so Italy stands at a cultural crossroad. In renewed proximity to the dangers posed by wild animals, Italians are being forced to reevaluate their relationship to nature, to confront a deep fear of wilderness and learn to live among it. Yet their country is perhaps the only place in the world that has been entirely cultivated for millennia, with little in the way of conserved spaces or cultural memory of how to live next to them. Of all places in the world, Italy may be uniquely unprepared for the return of the wild.

Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state, brown bears were hunted nearly to extinction — by the mid-1990s, just four were counted in the region around Trento, where Papi was killed.

For the past twenty-some years, however, an E.U.-funded program called Life Ursus has imported brown bears to Northern Italy to boost the region’s number of breeding pairs, taking candidates from its eastern neighbor Slovenia, where forests less pressed upon by human activity are still capable of sheltering a reasonably healthy bear population.

Though the program has undoubtedly succeeded in its aim — the brown bear population is now estimated at over 100 in the region — it has not been without controversy. By 2015, attacks on sheep and close contact with locals had become common enough to prompt warnings from the provincial authorities and a formal complaint to the European Parliament.

Andrea Papi’s assailant, it turned out, was a bear designated JJ4, a female descendant of a Life Ursus bear named Jurka that had been deemed “problematic” for its close encounters with humans, and moved to a sanctuary in Germany. Two of JJ4’s siblings had exhibited similar aggressive behaviors and had been shot and killed in neighboring countries. JJ4 herself had already once threatened humans, defending her cubs by charging at a father and son she encountered on a hike.

At the time of Papi’s death, JJ4 was seventeen years old — approaching old age for a bear. Her last litter of cubs, born in 2021, had already grown to independence. In a public statement, Papi’s mother vowed to “fight to the end to do justice,” and called on local leaders to “restore Andrea’s dignity.” Facing public outrage, the regional president, Maurizio Fugatti, decided that JJ4 would be captured and killed.

The decision incensed animal rights groups, including Italy’s Anti-Vivisection League (LAV), which volunteered to pay for the bear to be transferred to a sanctuary in Romania. Fugatti was painted as a bloodthirsty villain. Protesters gathered to chant “murderer” outside his home. An anonymous envelope addressed to his office carried a bullet, and a message: “the next one is for you.”

LAV spokespersons accused Fugatti of playing on the fears of locals for political gain. The government was “more interested in the moods of their electorate than in … the promotion of a peaceful and conscious coexistence,” their petition read. “On October 22, 2023 there will be elections,” Massimo Vitturi, a LAV campaigner, told the media. “And the theme of bears is very much felt in those parts.”

But in the end, it was not up to the politicians to decide. On July 13, after months of legal wrangling, the Council of State, a kind of high court to review the decisions of public officials, ruled that euthanizing JJ4 would be “disproportionate” to its crimes. “I wonder if there is still respect for human life,” Fugatti fired back. The decision “makes us wonder if the life of an animal or that of a human being is worth more.”

It’s still not clear what JJ4’s final fate will be, but the decision to spare its life has left concerned residents on edge. With an ever-growing number of bears forced into interactions with humans, the question of whose life matters more is no longer an academic one.

In Italian, there is no direct translation for the word “wilderness.” At conservation events and on nature reserve signs, you are just as likely to see it rendered in English — la wilderness — as its closest Italian correlates: deserto (desert), riserva naturale (nature reserve); or zona naturale incontaminata (uncontaminated nature area).

In many ways, Italians simply never knew an untamed wilderness like that which inspired the likes of Henry David Thoreau and the Wilderness Society in America. Already by the seventh millennium b.c., the historian Catherine Delano-Smith writes, Italy’s southern coastline was home to one of the most densely settled regions in prehistoric Europe, and to some of the world’s earliest farmers. Around scattered homesteads, hamlets, and then larger villages, prehistoric Italians were already clearing the pine and hazel scrub that were emerging after the retreat of Europe’s glaciers, defining the limits of ancient forests before they could even take a “natural” shape.

By the time of the Greek playwright Sophocles, in the fifth century b.c., it already seemed well understood that humanity had left a permanent imprint on the Mediterranean landscape. “Terrible wonders walk the world but none the match for man,” he wrote. “The oldest of the gods he wears away — the Earth.”

Among the ancient Romans, it was seen as a point of pride to “create a sort of second nature within the world of nature,” as Cicero put it. The gardens of the Roman grand villas were a model of “improved” nature and “a statement against its uncontrollability,” the historian Lukas Thommen writes. Dark forests were transformed into open groves and rolling fields; tumbling rivers into smooth waters leading into calm reservoirs. The ancient appreciation of nature, the historian Henry Fairclough found, was largely “confined to a sentiment for what is lovely and charming to the eye.”

By contrast, unmanaged landscapes, Thommen writes, were seen as barbarous, ugly, and undesirable — the place of wild animals, savage Germanic tribes, and questionable gods like the tricksy faun Pan. The same regions that would move later Romantic writers — think of the rugged peaks of the Alps — were labeled by Roman writers as ferus, foedus, horridus, occultus: wild, horrible, horrid, dark.

Slightly more respect was given to wild creatures — a she-wolf, after all, nursed the founders of Rome, and the wolf served as a totem animal for Mars, the god of war. Seeing a wolf thus became a good omen for Romans, even if they still needed culling, from time to time, to protect the rural farmer. (The first record of a wolf bounty appears to be from the sixth century b.c. — under the rule of Solon of Athens, a single male wolf could fetch five drachmas.)

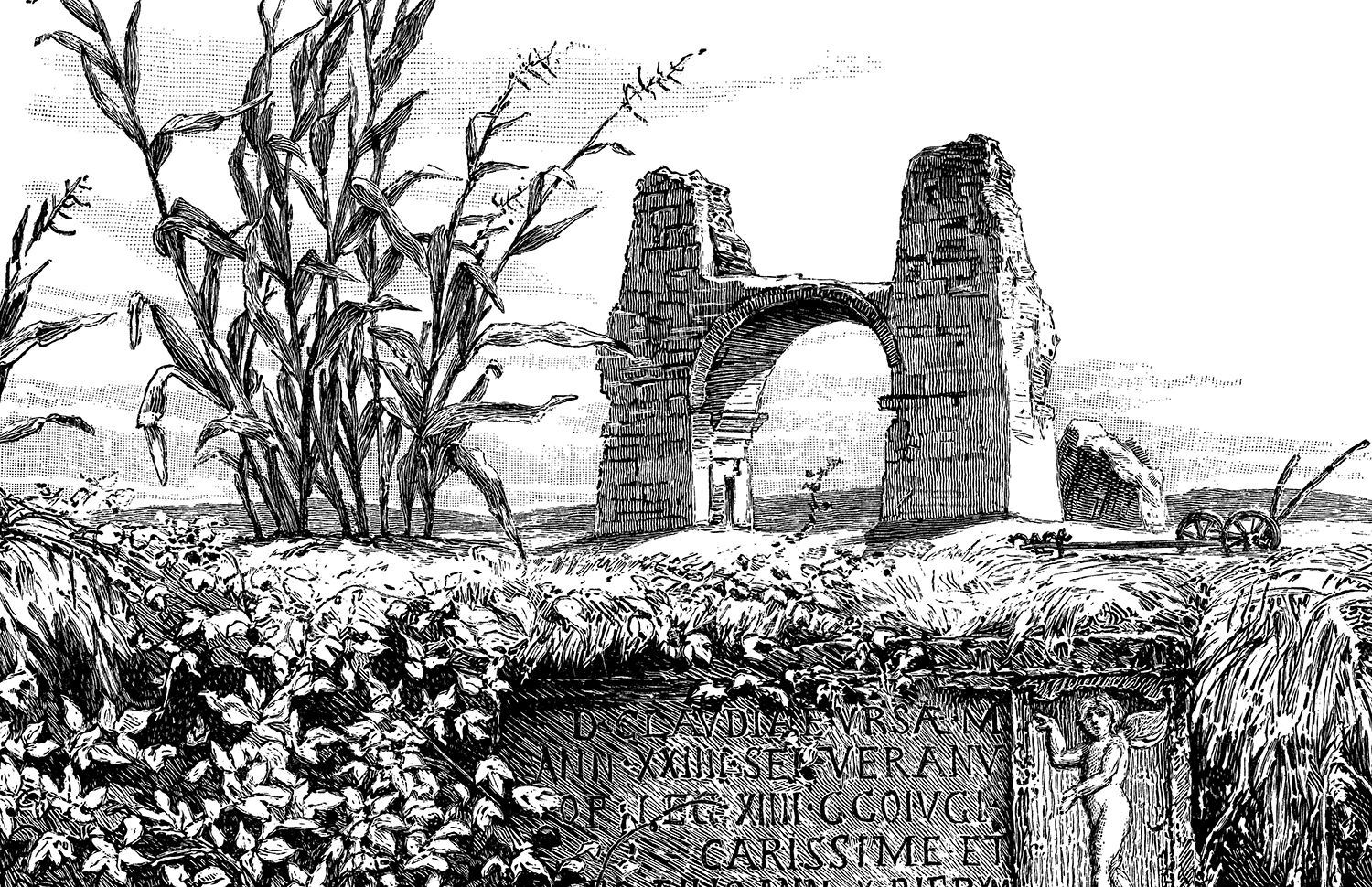

But other wild animals were not so lucky. Across the Roman world, vast numbers of untamed and exotic animals were hunted, captured, and slaughtered in circus spectacles. The emperor Augustus once boasted of holding 26 such animal hunts, killing 3,500 animals — his successors then tried to outdo him. Bears in particular suffered from this treatment; their remains turn up often in Roman ruins. By late antiquity, their sacrifice, the archaeologist Frank Salvadori writes, was “a symbol of the affirmation of urban civility and of Roman dominance over nature and the chaos associated with it.”

As Rome suffered its long decline, that dominance over nature became increasingly tenuous. Plague, civil war, invasion, and economic collapse combined to cause a rapid emptying of much of rural Italy, followed by the collapse of its villa-based system of agriculture. But while the end of Rome’s prosperity brought an end also to many of its decadent abuses of animals, this did not defeat the pessimistic vision of nature underlying those abuses. Instead, this vision seemed confirmed by the rapid reclamation of agricultural land by dank swamps and dark forests, which swallowed some Roman settlements whole.

When Italy reemerged from its dark age toward the end of the eighth century, many new communities had been established with a completely different relationship to their natural surroundings. Gone was the city in the open field, forests cleared back and enemies kept at bay by vast legions. The towns of medieval Italy were much more likely to be perched atop a hill, surrounded by natural defenses; the untamed wilderness the Romans despised became a useful ally against roving mercenaries.

But while cities and towns benefited from their closer contact with nature, the newly ascendant teachings of Christianity placed human beings in a new relationship to these surroundings. In Genesis, God gives Adam dominion over the garden he was tasked to keep, and nature in the Middle Ages was often viewed as a mirror of the human self. The monastic control of waters believed to have healing powers, and the felling of pagan groves, were motivated by the economic needs of the Church, yes — but also by the clear example they set of how nature, like the spirit, could be transformed from pagan savagery to Christian purity.

What wilderness that was allowed to remain was reimagined, as a distant place of trial and transformation, where the holy man could withdraw from society to test his faith against temptation. The animals of the wilderness took on an allegorical significance: the wolf and bear were coupled with the Devil, as symbols of the sins of rapaciousness, stubbornness, and anger. One eleventh-century relief from Germany even shows a bear whispering in the ear of Pontius Pilate. In his Divine Comedy, Dante departs the darkened wood of his spiritual confusion to encounter a panther, a lion, and a wolf — representing the sins of luxury, pride, and greed.

But like sins and temptation, beasts, too, could be overcome by holy men. St. Francis famously befriended the wolf of Gubbio, in Umbria, curing it of its rapaciousness. When a bear killed his horse, St. Romedius’s great gentility reportedly allowed him to tame and bridle it. He rode it through the Val di Non to visit a friend in Trento — through the very same mountain region where Andrea Papi jogged last spring.

As in the medieval stories, Italy has nearly always seen the wilderness as a place where human will triumphs over nature. Despite the wars and plagues that have from time to time depopulated it, Italy’s countryside has, for much of the last thousand years, been a bustling patchwork of small-scale agricultural activity. Its iconic terraced hillsides, like those in Cinque Terre, were home to family vineyards, orchards, and market gardens. A single rural town could support dozens of shepherding families and hundreds of sheep, fueling an entire industry of artisanal cheese production. Such small-scale economies shaped the Italian countryside by ensuring the continual presence of farmers on the land, keeping untamed nature — and wild animals — at bay.

But since the middle of the twentieth century, a change has been underway that is rapidly diminishing human influence over Italy’s landscapes. Since the Second World War, Italy’s rural areas have been emptying at a rate likely not seen since the collapse of the Roman Empire. Towns across the peninsula are aging and depopulating even to the point of disappearance. The marginalization of small-scale agriculture across Italy, and the growing divide in quality of life between the cities and their rural hinterlands, has erased what economic futures existed in the country’s mountain villages, plunging them into a deep demographic crisis.

Some small towns, like the hamlet of Cicogna in Italy’s Val Grande National Park, have seen their populations decline by over 95 percent over the past century. Robert Hearn, a researcher at the University of Nottingham who studies human geography in the north of Italy, said that in just the fifteen years he has been visiting the region, he has seen a marked decline. “We’ve seen towns go down to the last person,” he told me by phone.

In other regions, those families once charged with the generational task of maintaining the land are being displaced by mere visitors. Since becoming a hotspot for travelers, Cinque Terre has transformed from a collection of tiny seaside villages to a top destination for the summer homes of the rich and famous. Today, the families that once cultivated its terraced vineyards have given them up to run hotels and Airbnbs, or else moved away entirely. Around the town of Portofino, the land under cultivation has shrunk by 40 percent since the 1930s. Farming in the region, one study notes, has reached its “end stage.”

As they did during Rome’s collapse, these seismic demographic shifts are having profound impacts on the natural landscape. The steep terraces of Cinque Terre, a millennium old, are now crumbling from abandonment, accelerating soil erosion. Olive groves and vineyards are giving way to scrubland and forest.

In the town of Castelsaraceno, in Italy’s south, the number of sheep has dropped by 90 percent in the last few decades, leaving once vast common pastures unmaintained. Since 1936, the land in the region covered with forest has more than doubled. About a fifth of Italy’s forests are like this. But without owners to maintain them, they are increasingly vulnerable to forest fires and attacks by parasites.

Rural abandonment alone is problem enough, but the encroaching woods also provide convenient cover for wolves, bears, and wild boars, with which Italians have not had to share the land for a century. As the ecologists Pietro Piussi and Davide Pettenella have written, “depopulation is not simply a demographic process…. cultural values vanish too.” With the decline of rural life and the return of wild animals, many Italians are left with no cultural memory of the animals they increasingly come into contact with, and no knowledge of how exactly to deal with them.

In Liguria, Robert Hearn found, wild boars had been a distant memory since at least the 1860s, hunted to extinction by aristocrats. When boars started to return as the countryside emptied in the 1960s, the first man to kill a boar on a hunt, having no experience with the animal, didn’t know how to bring it home, nor did those cooking the meat know how to prepare it, so it was eaten half raw.

Today, however, wild boars number more than 80,000 in Liguria alone. Some 2.3 million trouble farmers across Italy, trampling fields, devouring crops, damaging fences, and spreading disease. This rapid growth has given rise to wild speculations. When boars first proliferated, farmers in Liguria imagined that they had swum there from Sardinia, or been imported from Hungary by environmental activists or hunting enthusiasts. Some even blamed a single mysterious “doctor from Parma.”

But the reality was more mundane. Boars no longer needed to compete with humans and evade hunters to survive. Instead, they had ample abandoned chestnut groves and gardens to feed on. “If the woods were clean there would be less problems,” one farmer told Hearn. “But now it’s too dirty, too full of food for them, and so they have more litters, and so cause more damage.” In his interviews, Hearn found more than a few old-timers for whom damage caused by boars was the last straw that made them quit farming altogether and abandon their lands. It’s become a bitter cycle.

Boars may destroy ancient infrastructure and make commercial farming less viable, but they can at least be hunted as a source of food — today, their meat is increasingly common at local-food festivals. But the same feedback loop of rural damage, abandonment, and animal proliferation also benefits more dangerous predators like bears and wolves.

Fifty years ago, it was estimated that there were just a few hundred wolves left in Italy. “Now, we are talking about 4,000,” Luigi Boitani, a biologist at the Sapienza Università di Roma and one of the world’s leading experts on large predator reintroduction, told me over Zoom. “We have not had so many wolves in 500 years.”

Although boars cause far greater damage, wolves uniquely play on fears of rural abandonment. Their gradual encroachment on cities and towns is like something out of a dark fairy tale. For centuries, the ecologist Henry Buller wrote, “the wolf has … held an iconic status, largely as a powerful, savage, and menacing natural otherness.” It has long been “the enemi sans pareil for shepherds and farmers across the Earth,” known for menacing sheep and other livestock, kept at bay only by constant vigilance.

With wolves once hunted almost to extinction, Buller writes that in the second half of the twentieth century they underwent “an almost ontological volte face,” an about-face. Increasingly, they were viewed as victims, not vermin, in need of protection as a vulnerable species at risk of disappearance. As Buller notes, this shift reflected a fundamental change in attitude about the relative value of wild and managed natural landscapes in Europe. Importing ideas from the American wilderness movement, European conservationists sought to carve off spaces immune from human contact, and saw top predators like wolves as “symbolic heralds of a newly reinvigorated naturality.”

But many rural land users have begged to differ. The pasture lands and rural landscapes they and their forebears have managed for centuries are now far more difficult to maintain with large predators feeding on their flocks. Thousands of livestock animals are killed by wolves in Italy each year. France counted about 10,000 in 2019. Hearn told me he once interviewed a farmer who had purchased sixteen sheep with his pension and lost them all to wolves within two weeks. “He just starts weeping in his kitchen,” Hearn recounted.

Some skeptical ecologists — alongside many rural opponents of wolf conservation programs — see pro-wolf efforts as reflective of an increasingly urbanized society, where people are less likely to fear wolves because they are less likely to encounter them. Others see outright conspiracy: efforts by environmentalists and conservationists to undermine farmers, devalue their work, and push them from the land.

But wolves, Buller writes, are simply opportunists. In France, wolves have proliferated because of an unnatural abundance of food — some 50 percent of their diet is estimated to be domesticated sheep, and it is unlikely that wolves could survive in large numbers without access to such an ample food supply. Their growing proximity to managed nature makes their abundance possible.

Rural depopulation exacerbates this problem. It is bringing the woods that wolves use for cover closer to human settlement, and giving them more space to proliferate unchecked, to the point that their status as a protected species in the European Union is now in doubt. “If we have so many wolves in Italy now, it’s because of the abandonment of mountain agriculture,” Boitani said. “The best definition of a wolf habitat is: anywhere where there is anything to eat and they are not shot. And there is plenty of that in Italy.”

Rural abandonment is also erasing the cultural memory of how wolves were, for millennia, part of rural life. Boitani postulates that ancient Mediterranean farming societies could manage wolves better because, with long-term exposure to one another, “you learn about the wolves around you, and leave the possibility of the wolves learning about you.” By contrast, today’s wolves are strangers passing through an empty landscape.

The reintroduction of bears to the Trento region has been more deliberate than the largely unplanned resurgence of the wolf, but the response so far of rural residents has been about the same. Andrea Papi’s tragic death has reignited debates first prompted by the wolf about the balance between biodiversity and safety, and whether it is wise to bring big predators back to a region where humans have enjoyed unchallenged dominion for so long.

The bears’ defenders are not without examples of successful coexistence they can point to. In the central Italian region of the Apennine Mountains, an isolated population of a few dozen brown bears has lived alongside rural communities for centuries. Locals maintain an overwhelmingly positive attitude toward them, appreciating even the way the bears fearlessly encroach on human settlement. The death of a three-year-old bear named Juan Carrito, famous for swiping biscuits from local bakeries and resisting efforts to banish him to distant mountaintops, was treated like the passing of a local celebrity.

But amid the spirit of fear and vengeance that has gripped Trento in recent years, it would be naïve to suggest such a friendly relationship could be easily created, even with years of outreach and education. The bear-loving culture of the Apennines is born of five centuries of close coexistence — the first written records of bears in that region go back to the fifteenth century. With their small, condensed population, these bears live only by the continuing consent of the people that surround them. In this sense they are not really wild at all, and locals have long learned to manage what inconveniences the animals occasionally pose.

“Coexistence was achieved by a lot of tolerance toward the animals themselves and toward the damage caused by them,” Boitani said. “If the damage is above a certain level, the traditional method of the local shepherd involves killing some of them. So, there is this balance.”

The virulent reaction to the case of JJ4 by animal rights activists, who treat every animal’s life as sacred, suggests that such a balance may no longer be possible to strike in places where coexistence with large predators is a new phenomenon, and where the desire to occasionally enact revenge will be the greatest. Here, Boitani suggests that conscious displays of human domination — including, in some situations, the decision to kill a predator — may be a necessary cost for maintaining local support for the predators, by restoring a sense of control to residents. “That authorization for killing … is actually a powerful political tool,” Boitani said.

Maurizio Fugatti, president of the Trento region, appears determined to exercise this power. Seemingly in response to the high court’s decision to spare JJ4’s life, Fugatti ordered the deaths of two wolves in a historic first, ostensibly to assuage local concerns that they were increasingly attacking cattle herds. That decision, too, was suspended following challenges from animal rights groups. Lacking official sanction, it appears residents are turning to more extreme measures. Since Papi’s death, bears have been turning up dead in the woods around Trento, likely the result of illegal poaching. In fighting to spare JJ4’s life, Boitani said, animal rights activists may have won a battle but lost a war — “because now, the greatest majority does not like the bears.”

Those who would exercise their powers over nature to push large predators once again near to extinction may be fighting a losing battle, too. In much of Italy, such domination could at best be only a temporary illusion. As Boitani points out, these animals are proliferating because human beings are no longer active enough in rural areas to manage and define the emerging wilderness as they once did. Facing a retreat of human settlement on such a massive scale, many Italians will not have the privilege of deciding what kind of wilderness they will live beside.

That means that Italy’s future wilderness will likely be neither the scientifically constructed Eden of rewilding advocates nor the strictly bordered liminality rural residents might want. Instead, it may become something less controlled — and more threatening — than either side would like to admit. But such a shift may present an opportunity, of sorts, to redefine the Italian relationship to wilderness in a way that is much more authentic to European history than the idealism of American conservationists that has so far held sway.

Throughout the long history of wilderness as a concept in Europe, one quality has perhaps been the most enduring and essential: fear. For the ancients, wilderness was a place of supernatural beasts and evil portents; for medieval Europeans, a dangerous frontier inhabited by unknown perils and temptations. When the Italian Baroque painter Salvator Rosa tried to revive an appreciation of rugged nature, it was the sensation of terribilità he tried to evoke — a sublime sense of power, beauty, and danger.

Today’s Europeans are perhaps well primed to feel this fear again as the ancients did. Robert Hearn notes that as Europeans’ encounters with wild animals have become less common, “a certain childishness” has crept into their relationship with nature — a naïve love of animals coupled with a petulant demand for control. But as many Italians are rapidly learning, wild animals are not saintly sidekicks and cheeky bandits, and neither are they sacred creatures possessed of the kind of individual dignity that makes their death in every case a crime.

A more mature relationship to these creatures may require the embrace of respectful fear, the kind that defined the attitudes of the Romans and medieval Christians: recognition, in these animals’ strength, of our own weakness, of the limits we once felt more freely to our power over nature.

It may be the case that no true wilderness is possible without such existential fear. Successful coexistence with wild animals, Hearn says, comes down to “people’s willingness to lose” — lose their crops, their animals, and maybe, from time to time, even their very lives. In exchange, we receive terribilità: a perspective, for a moment, outside ourselves, where we see that our terrific wonders can sometimes be terribly small.

Keep reading our Winter 2024 issue

The sky is not falling • Tech is so back • Italy goes wild • Barbie vs. Botox • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?