Doctor Kay Redfield Jamison, a clinical psychologist, chaired professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, honorary professor of English at the University of St. Andrews, author of now seven books for the general reader on psychiatric subjects, co-author of the standard textbook on manic depression, and MacArthur award recipient, is the most important writer we have on severe mental illness. For the past thirty years she has charted the vagaries of sick minds and agonized souls, with her focus on manic-depressive illness — still her preferred name for what is now called “bipolar disorder.” Though the older term has fallen out of fashion, she finds it both more precise and more evocative than the one currently favored, which could apply to a car battery on the fritz or a geopolitical kerfuffle between rival superpowers. The more anodyne term for this frightful disease is believed to spare sufferers and their families the stigma of the depressed maniac. Sometimes, however, it is useful to give the frightful its full measure of respect by acknowledging openly how terrifying it can be.

Jamison has rendered the terror of psychotic mania with unsparing clarity. An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness (1995) recounts her own struggles with manic depression, including a vision she had upon gazing at a sunset in 1974, during her first summer as an assistant professor of psychiatry at UCLA. She saw herself carrying a large tube full of blood to an immense black centrifuge. She inserted the tube into the machine, the machine began to whirl, and the picture in her head took life before her eyes, as real as anything else in the room.

The spinning of the centrifuge and the clanking of the glass tube against the metal became louder and louder, and then the machine splintered into a thousand pieces. Blood was everywhere. It spattered against the windowpanes, against the walls and paintings, and soaked down into the carpets. I looked out toward the ocean and saw that the blood on the window had merged into the sunset; I couldn’t tell where one ended and the other began. I screamed at the top of my lungs.

This is madness, bedlam, lunacy — a few more words considered just too much for us these days, too reminiscent perhaps of Victorian phrenic dungeons and lobotomizing icepicks through the eye socket. One cannot really blame the psychiatric language sanitizers, who surely mean well; but Jamison’s frankness about what this disease does to the mind — what exactly it did to her remarkable mind — makes such euphemism seem a sort of cowardice.

She enjoyed the great good fortune of the immediate attentions of a colleague she knew very well, who diagnosed her correctly, prescribed her the mood stabilizer lithium and some antipsychotic medications, convinced her to start seeing another psychiatrist straightaway for regular treatment, and advised her to take a brief hiatus from work, enabling her in the end to keep her job and clinical privileges.

Even the best good fortune has a way of running out, though, when one is dealing with a lifelong mental illness that has a prodigious mortality rate. The medicine that, if all goes well, is the patient’s salvation can also be repurposed for self-destruction. At twenty-eight, Jamison deliberately gulped down “poisonous quantities” of lithium and nearly succeeded in killing herself. Depression rather than mania was the near-fatal horror here.

In Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide (1999), she recalls giving a barbed answer to a dinner companion, a psychiatrist who in his youth thought fleetingly of suicide, and who somewhat pompously declared that love for his family and friends and concern for his patients would make it impossible for him to end his own life. When Jamison took her potentially lethal overdose, she was way past thinking of how her death would affect her loved ones. She “did not consider it either a selfish or a non-selfish thing to have done,” she writes.

It was simply the end of what I could bear, the last afternoon of having to imagine waking up the next morning only to start all over again with a thick mind and black imaginings. It was the final outcome of a bad disease, a disease it seemed to me I would never get the better of. No amount of love from or for other people — and there was a lot — could help. No advantage of a caring family and fabulous job was enough to overcome the pain and hopelessness I felt; no passionate or romantic love, however strong, could make a difference. Nothing alive and warm could make its way in through my carapace.

Death beckoned with the promise of relief — freedom from the tyrannical regime of unending desolation. It was the sole hope available at the time.

A few weeks later, waiting for a Bach concert to begin in the Episcopalian church where she was an often truant parishioner, she knelt and began reciting a rote prayer asking God to be present in her mind and senses, hoping this would be “an act of reconciliation.” She could not remember the last words of the prayer at first, but then they came to her: “God be at mine end, and at my departing.” A “convulsive sense of shame and sadness” struck her, a feeling she had never had before nor has had since. Where God had been in the hour of her crisis remained a mystery. Yet maybe her survival had not been sheer accident: “I do know, however, that I should have been dead but was not — and that I was fortunate enough to be given another chance at life, which many others were not.” A gift of such magnitude one does not take lightly.

Jamison’s subsequent career as clinician and writer has made good on her second chance. And now with her latest book, Fires in the Dark: Healing the Unquiet Mind, she has turned to the supreme practitioners of the healing arts, taking that phrase in the widest sense to encompass conventional psychotherapy in its various incarnations, psychopharmacology, surgery, priesthood, myth, music, poetry. Her great theme is the courage of men and women who have reckoned with suffering of their own — often extreme suffering — and made it their source of strength.

The original wounded healer, Jamison suggests, citing the medical historian Stanley Jackson, was the centaur Chiron, whom his mother abandoned when he was young and who suffered a crippling wound from a poisoned arrow. His experience of severe pain schooled him in appreciation for the pain of others; he became an adept healer and teacher of healers, even a trusted advisor to some of the greatest Greek warriors and to the gods themselves. “He was tutor to Achilles, Dionysus, Odysseus, and Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, all of whom learned well and lastingly from their wounded healer,” Jamison writes.

Before the physician can presume to heal others, reads the inscription on an ancient monument to Asclepius, he must first “heal his [own] mind.” This imperative applies as well to priests, shamans, and the modern psychotherapeutic geniuses Freud and Jung. “It is the doctor’s own hurt, Jung believed, ‘that gives the measure of his power to heal.’” Jamison does not go into Jung’s own formative trial by fire, which is detailed in the posthumously published Red Book, an episode of harrowing psychosis that would likely have destroyed most lesser men but instead taught him to have no fear of the mind’s contents, however monstrous they might seem. Having felt his own seething unconscious erupt into the midst of normal daylight reality served Jung well in his treatment of schizophrenic patients, who in Freud’s judgment were too far gone to reach, but whose bizarre hallucinations and delusions Jung attempted to comprehend with respect and tenderness. Unlike Freud, who maintained a studied distance from his patients, sitting aloof and serene out of the supine sufferer’s sight, Jung would sit face to face with his charges, bumping knees, exhorting with vehement gestures.

In Jung’s estimation, what healed was not disinterested mind alone following a dogmatic trail through the vast wastes of one’s sexual history, but making contact, demonstrating sympathy, aiming at a comprehensive understanding, allowing the free play of humanity at its best. Jung could see that for patients above the age of thirty-five — life’s halfway mark, or what Dante called nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita — their principal concern was not undoing childhood psychosexual knots that persisted into adulthood, but rather finding the authoritative spiritual truth that one could found a serious life upon.

The spiritual life of gifted healers — especially their relation to the natural evils they devote themselves to combating — occupies a prominent place in Jamison’s account. Some of the finest doctors suffer under a pall of ineradicable sadness as they do their best to ease others’ suffering.

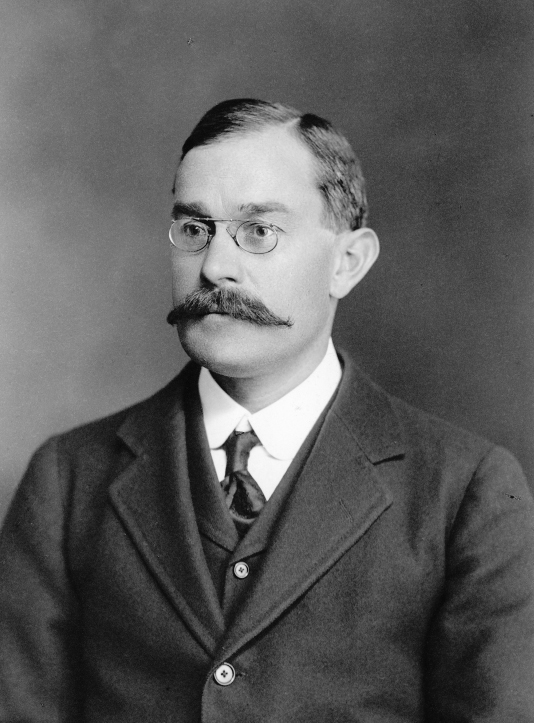

Sir William Osler, the first physician-in-chief at Johns Hopkins Hospital in the late nineteenth century, later a professor of medicine at Oxford, and widely hailed today as “the father of modern medicine,” was prone to such constitutional overcast. A colleague who saw him most every day for fifteen years said, “melancholy seems to me to be his essence, almost his driving force.” The more profound sadness of indefinite and inconsolable mourning came to plague him when his beloved son and only child, Revere (whose great-great-grandfather had been the Boston silversmith of the historic midnight ride), died in the futile mass butchery of Passchendaele in 1917. The doctor’s wife could hear him “sobbing hour after hour”; at the hospital Osler would make rounds “in his same gay old way,” a friend remembered, but on returning from work he could not restrain his grief and “he sobbed like a child.” The suffering doctor seemed to recognize there was no real cure for this heartbreak, that he could only ride it out and distract himself by unstinting labor: “We are taking the only medicine for sorrow: Time and hard work.”

Osler drew wisdom and strength from the books by two seventeenth-century writers, whose classic works he read over and over: Religio Medici, by the physician and naturalist Sir Thomas Browne, and The Anatomy of Melancholy, by the vicar and Oxford don Robert Burton. Jamison quotes Browne on the dynamic relation between the patient’s pain and the doctor’s: “By compassion we make others’ misery our own. And so, by relieving them, we relieve ourselves also.” Burton, for his part, wrote of his own misery in order to cauterize the mental lesion at its root: “I was fatally driven upon this rock of melancholy. To ease my mind in writing, I writ of melancholy, by being busy to avoid melancholy.”

Jamison joins Burton and Osler in describing the shared enterprise of doctor and patient, the importance of faith in healing mind and body, and the therapeutic benefit of reading the right books, or of writing them: “Sufferer and physician must be actively engaged in the treatment of melancholy, Burton’s Anatomy taught. Faith and medicine must be brought to bear, minds prized open. Osler found in Burton the affirmation that work could heal when other things did not, and that writing about one’s suffering might help others also in pain.”

Jamison’s book abounds with heroes, but her particular favorites appear to be Dr. W. H. R. Rivers, a Royal Army psychiatrist stationed near Edinburgh during the First World War, and his famous patient Siegfried Sassoon, poet, decorated paragon of courage under enemy fire, and notorious anti-war dissident. Recipient of the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry, Lieutenant Sassoon in 1917 wrote in a declaration read aloud in Parliament, “I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolonging those sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.” The not entirely honest testimony by fellow poet and soldier Robert Graves that the battlefield had driven Sassoon out of his mind might well have saved him from being charged with treason.

It is also why Sassoon was sent to Dr. Rivers. When Sassoon asked the doctor if he thought he was suffering from shell-shock — the dire psychic and nervous affliction that would be called battle fatigue in the Second World War, and that is known as post-traumatic stress disorder today — Rivers responded with a laugh: “Certainly not. You appear to be suffering from an anti-war complex.” Sassoon obviously did have a wounded mind, though, however his distress might be defined, and it would become Rivers’s sad duty to render him fit enough to fight again.

Rivers was the sterling product and representative of the most august English institutions — the son of an Anglican priest, he was a fellow of St. John’s College, Cambridge, and a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Polymath learning and personal rectitude formed the core of his being. “He was widely recognized as an anthropologist, ethnologist, neurologist, psychologist, medical psychologist, and psychiatrist,” writes Jamison. “In each field he left a mark.” Much more than a walking encyclopedia, he convinced by his presence. This morally formidable man overcame serious vulnerabilities. He had a weak heart, and would die quite suddenly at fifty-eight. Moreover, although Jamison does not come right out and call him manic depressive, she describes cycles of strenuous enthusiasm and unrelenting work succeeded by pangs of gloom and uselessness. Getting on tolerably with himself involved continual negotiation with his several demons. Like Melville’s Ishmael, Rivers would take to sea for the good of his soul when the landlubber world proved more oppressive than he could stand.

The demanding values of the imperial ruling class — God, honor, country, one might call them — were bred in the bone not only for Rivers but for the soldiers who were his patients. It was not until he had seen what twentieth-century mechanized warfare could do to the most stalwart men that Rivers thought to question the inviolability of these values. When the manliness inculcated since boyhood came up against unexampled terror and savagery, the most cherished virtues — prominent among them Jamison lists “duty, restraint, bravery, loyalty, and adherence to rules” — fragmented and even disintegrated like a body ripped apart by shellfire. Yet while Rivers possessed an unusually developed capacity for sympathy, and suffered with those he saw suffer, in the end he upheld the integrity of those institutions in whose name the soldiers’ suffering was believed necessary.

Steeling soldiers in advance against the worst they will have to endure was the most prudent course in Rivers’s view; prophylactic doses of imagined horror made the best medicine — an ounce of prevention. The Stoic prescription of Seneca’s, Jamison writes, held true for Rivers centuries later: visualizing calamitous events reduced one’s susceptibility when bad things came to pass. And when a man had actually been through the worst and his mind needed repair, thinking peaceable thoughts, as many doctors recommended, would not do. Deliberately to summon the most fearsome memories and to face them down provided the pound of cure. Hard terms for these hard times, which only the hardest men survive more or less sound.

Yet severity alone was insufficient; for Rivers the job required a priestly sensitivity that encouraged the patient to confide the secrets of his soul to his doctor. “Some of the modern measures of the physician,” Rivers writes, “are little more than his adoption of modes of treatment which have long been familiar, in the form of confession, to the priest.” It was his hope that the modern profession of healing was “again bringing religion and medicine into that intimate relation to one another which existed in their early history.” Sassoon would speak of Rivers as his “father-confessor,” to whom he entrusted the darkest part of himself.

Jamison goes further still, writing that “Rivers surely held the power of priest-sorcerer for Sassoon.” There is a deft touch of wizardry to his methods. “He recognized the power of ritual, the legacy of ancient gods, and ‘cities with dead names’; the force of personality of the healer and the strength of human longings, ancestral symbols, myths, and the indisputable sway of suggestion. The efficacy of healing is ‘largely ascribed to the personality of the sorcerer,’ Rivers wrote. ‘Some degree of confusion between personality and [healing] runs through the whole history of medicine.’”

Yet again, this bond of spiritual intimacy was not enough either. Self-analysis, the work of exploring one’s most wrenching feelings in the light of unflinching rationality, was indispensable to healing. Rivers undertook to convince Sassoon to understand himself with the utmost lucidity, free of all beguiling psychic haze: Without knowing oneself, the broken mind was “enveloped by a sense of mystery which greatly accentuates the [negative] emotional state,” Rivers once wrote. And Sassoon kept his part of the bargain by agreeing to train the analytic searchlight on his renegade thinking, “keeping one side of my mind aloof, a watchful critic.” Fully to realize what killing, nearly dying, and leading his subordinates into the midst of slaughter have done to his soul: this is the task that Rivers set for Sassoon, the ordeal of recovery compounding the ordeal of battle he is recovering from.

When Sassoon was discharged from the hospital in November 1917 after a twelve-week stay, his confidence in Rivers’s power to heal was passionate and total. Rivers, in his advisory directive to the army medical board, had left Sassoon the alternative to return to England rather than to the Western Front, but for Sassoon there was no choice: he needed to return to battle and to his men. After postings to Ireland and to Palestine — Rivers had recommended that the board delay the patient’s return to the trenches, for which his nerves were still unready — Sassoon was back in France in May 1918, where he was presently shot in the head by a British soldier who took him for a German. The wound was not fatal, and he was sent to London to heal. In Sherston’s Progress, the third and final volume of his memoirs of fox hunting and total war, Sassoon remembers sitting in his hospital room emotionally disoriented and even longing to be killed.

And then, unexpected and unannounced, Rivers came in and closed the door behind him…. My futile demons fled him — for his presence was a refutation of wrong-headedness…. I knew that I had a lot to learn, and that he was the only man who could help me…. He did not tell me that I had done my best to justify his belief in me. He merely made me feel that he took all that for granted, and now we must go on to something better still. And this was the beginning of the new life toward which he had shown me the way.

The sort of transformative energies that Siegfried Sassoon attributes to the healing genius of Dr. Rivers are the same, for Jamison, that great works of art, philosophy, and sacred wisdom possess. They search your depths, but only if you are willing to search yourself as part of the process.

The depths can become apparent even in childhood, Jamison writes, if one is introduced to literary “exemplars who will add the heroic, romantic, and courageous to stories. Someone larger than life, with an epic vision. Someone who paints on a great canvas. Someone who will inspire ambition, show ways to overcome setback and pain.” Jamison sets great store by the virtues that all would do well to acquire, especially courage in the face of suffering, which is inevitable even in the most charmed human life. The young need to learn “that failure and death may accompany great accomplishments; and that suffering and setback can be used to advantage.” They need initiation into the tragic sense of life, to complement their feeling of wonder at existence, their taste for the fantastic, and their eagerness for adventure.

Some of Jamison’s favorite books to encourage mental vigor are ones like The Worst Journey in the World. English explorer Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s memoir recounts the famously tragic 1910–1913 Antarctic expedition led by Robert Falcon Scott, which was outraced to the South Pole by the amazingly efficient and fortunate Norwegian Roald Amundsen.

Even prior to the expedition, Scott had endured awful spells of depression, while years later Cherry-Garrard would fall prey to a virulent depressive psychosis, the origins of which Jamison suspects to have been in his polar ordeal, and for which he would take to his bed literally for years. “His cracked mind,” writes Jamison, “was testament to the limits of courage.” The conjunction of the frightful and the glorious in their lives is the stuff of extraordinary heroism; here Jamison quotes Cherry-Garrard on “running appalling risks, performing prodigies of superhuman endurance, achieving immortal renown, commemorated in august cathedral sermons and by public statues, yet reaching the Pole only to find our terrible journey superfluous, and leaving our best men dead on the ice.”

T. H. White, author of The Once and Future King (in four volumes, 1938-1958), his masterly retelling of the Arthurian legend, was another intimate of profound psychic disarray — likely a manic-depressive “chased by a mad black wind,” in a friend’s words — who sought healing from persistent unhappiness through many-sided excellence with a dreamer’s flair. “He learned how to fly, plow, hunt with bow and arrow, hunt with falcons, gear himself in medieval armor, and go into the sea in old-fashioned diving suits,” Jamison writes.

He forced himself to be more courageous than he believed himself to be, and to venture where he had not gone before. He read and studied voraciously. He worked on his writing; he sketched. He put into practice his belief that suffering could come to good, and that writing from suffering could help others. (White’s gravestone reads, “T. H. White / 1906–1964 / Author / Who from a Troubled Heart / Delighted Others / Loving and Praising / This Life.”)

Which is not to say that there isn’t a large portion of this life, as White presents it in his work, that is baneful and worthy of scorn. Arthur’s death and Camelot’s ruin will be tragic, as human evil, blind mischance, and the moral frailty even of the finest men and women combine forces to bring down the most nearly perfect chivalric regime. To mitigate the ugliness of life’s blackened underside, as the wise-hearted sorcerer Merlyn teaches the young Arthur, learning offers the one sure remedy — and only a palliative at that:

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlyn, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That is the only thing that never fails…. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

The mind’s resourcefulness in redirecting toward health its own wayward and most disturbing impulses is remarkably subtle and almost endlessly various. The ways of righting a mind gone wrong are sometimes best known to those whose own minds may be seriously out of sorts. Not infrequently it takes one unquiet mind to heal another, or to ease its own distress. Dr. Jamison is one of those paradigmatic healers who have been through hell and have come back bearing rich gifts for their afflicted brothers and sisters. Fires in the Dark represents a lifetime’s hope, strength of character, and downright wisdom engaged with the perversities of nature that appear bent on destroying them all. It is heartening to see the forces of light massed heroically and happily for the fight.

Algis Valiunas is a New Atlantis contributing editor and a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?