ITEM: Insects are an ideal source of protein for denizens of a world facing climate change and a growing population.

ITEM: The rise of government-assisted euthanasia produces a new source of organ donations.

ITEM: A new startup that specializes in composting people seeks to raise $5 million in its latest funding round.

Scenes from a 1970s dystopian science fiction film? Nah, just typical headlines from the past year. How apropos, then, that it should be the fiftieth anniversary year of one of that subgenre’s most iconic films, Soylent Green. And, while we’re counting anniversaries, we’ve just passed the year in which that story was set, 2022.

But, to paraphrase the film’s central mystery, what is Soylent Green? It is many things: dystopian science fiction, kitsch, excellent meme-fodder, a showcase for Charlton Heston (who is simultaneously a genuine charismatic and one of cinema’s great hams), and more. It came out of that fertile late-1960s and early-1970s period of imaginative fiction, in which the gee-whiz optimism of the early postwar era gave way to increasing pessimism and even nihilism, and cosmic anxieties became metaphors for social ones, and vice versa.

Like most major science-fiction movies, it is based (loosely) on a novel, the mostly forgotten Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison. And, like many science-fiction films — including 2001: A Space Odyssey, Back to the Future II, and Blade Runner — the action takes place in a future that has now already passed. Soylent Green’s then-distant future of 2022 is one of desperate overpopulation, global warming, and class inequality. The few rich live in fortified compounds and have access to regular food and water, while the many poor must rely on synthetic foodstuff, mass-produced by the powerful Soylent Corporation. A partial solution to the demographic crisis is euthanasia.

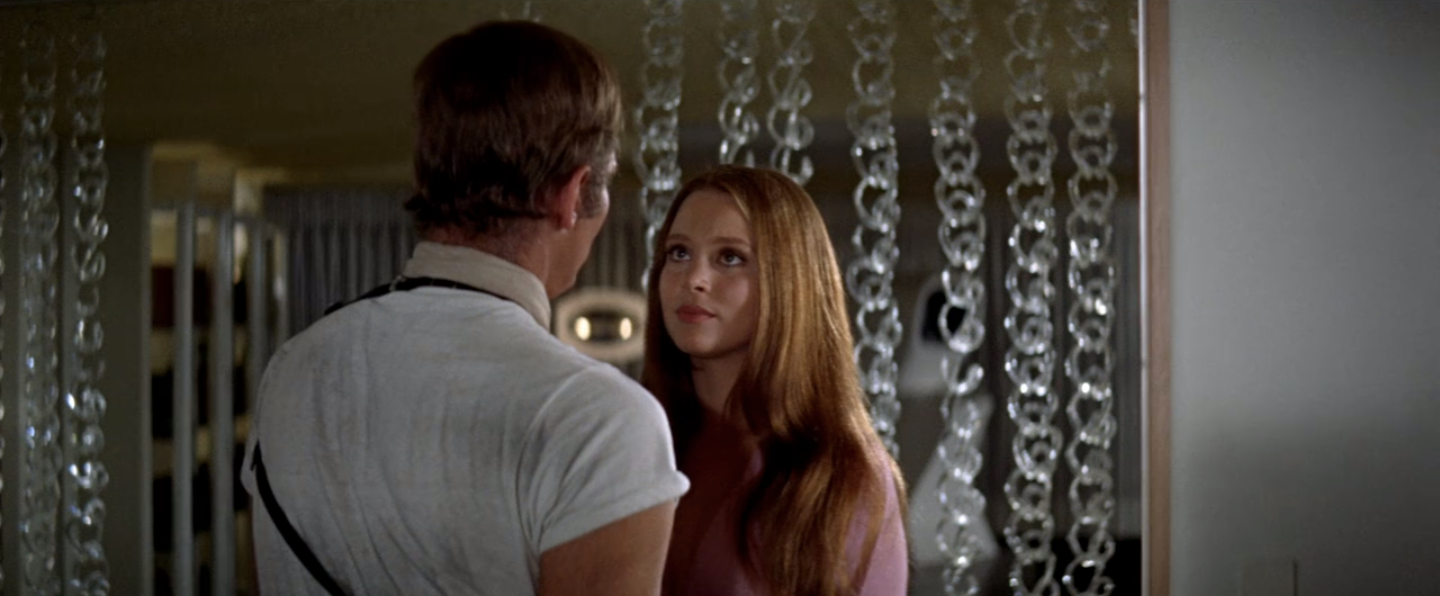

The story centers on an NYPD detective, Robert Thorn (played by Heston), who uncovers a conspiracy spanning the government, scientific elites, and of course the Soylent Corporation. Through a series of plot machinations too convoluted to elaborate here, he discovers that the synthetic food Soylent Green is in fact made from the corpses of the recently euthanized, leading to the film’s famous climax, in which he reveals the awful truth.

It is a testament to the film’s resonance that many people who have never sat through an entire viewing of it nonetheless know its famous concluding scene — up there with the ending of Planet of the Apes (another Charlton Heston sci-fi showcase) for producing a cultural legacy that has outgrown that of the movie itself.

Memes and pop-culture punchlines aside, the film’s imagery is also replicated in many recent treatments: Idiocracy, WALL-E, Cloud Atlas, Elysium, Ready Player One. The picture of resource depletion and population fears proved so potent that it was employed to dramatic effect in the cinematic adaptation of Children of Men, despite that film’s relying upon precisely the opposite premise: the threat of human extinction. And Soylent Green’s iconic denouement recalls Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” and William Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, among other memorable depictions of cannibalism — not bad for a dated sci-fi flick.

But the film’s enduring place in our collective memory is due less to the many spinoffs it has generated over the years than to its depiction of overpopulation in what the invaluable TV Tropes website refers to as a “crapsack world.” Climactic reveal aside, the thing most viewers probably recall is the images of city streets filled with the teeming masses of humanity bereft of basic resources. In fact, a terrifying detail in the film — the death of all the world’s marine life — is kept offscreen.

Of course, overpopulation fears were hardly limited to the domain of imaginative fiction. Amid exponential population growth worldwide, the postwar era saw widespread expressions of concern, crystalized by Paul Ehrlich’s bestselling 1968 book The Population Bomb, which erroneously predicted the deaths of hundreds of millions of people through starvation within a decade.

But the Malthusian nightmare did not come to pass. While the population of the United States (not to say the world) has increased substantially in the intervening years — growing nearly 60 percent since 1973 — apocalyptic fears of overcrowding and mass starvation did not materialize. In fact, throughout most of the world, demographic collapse is the more likely future, as birth rates continue to decline. Meanwhile, our agricultural output has been keeping pace with population growth thanks to the Green Revolution (though its benefits are not yet entirely global). If you lifted an extra out from inside the world of Soylent Green and deposited him in our own present day, one imagines he would be astonished at the world of plenty he now inhabits.

Is Soylent Green then merely a curio — a Seventies relic like The Late Great Planet Earth or pet rocks? Perhaps not. For technological advancement is not a panacea for social ills. And while our own story (so far) has averted the apocalypse, we have not averted some of the more dystopian implications of that era’s speculative fiction.

Our political and economic elites have already begun promoting austerity and privation for the masses (“I own nothing … and life has never been better,” as a writer for the World Economic Forum put it), even going so far as to endorse insects as the new meat, despite the global apocalypse not yet having undergone the formality of actually occurring. Meanwhile, in the film’s telling, radical inequality driven by severe material scarcity also involved the commoditization of sex. Women pass from tenant to tenant along with the lease on the most desirable apartments, and are literally called “furniture”; we, however, have needed nothing like that degree of social and economic desperation for sex trafficking to become widespread.

Above all, as it turned out, we did not have to wait for catastrophic overpopulation in order to resort to euthanasia. Soylent Green offers some queasy-making parallels with, say, Canada’s assisted-dying program, which is presently positioned at the forefront of guaranteeing widespread access to euthanasia. We see the similar deployment of gauzy, euphemistic language (“dying with dignity” versus the film’s “going home”) for what has proven to be an expedient procedure, with news reports abounding on how euthanasia stands to save the healthcare system millions of dollars a year. More disconcertingly still, the same instrumentalizing of the human body as in the film has made Canada the world’s leader in organ donation from euthanasia.

One can argue in response (as its advocates do) that euthanasia as currently practiced is a kindness — indeed a form of care. But this is a dodge. Euthanasia as depicted in the film is in its own way a release from a genuinely unpleasant existence. Even the horrifying use of human bodies as processed food is not driven by profit-seeking or evil for its own sake, but by terrible necessity as other sources of nutrition have died out.

All this said, Soylent Green is something less than a classic of science fiction. It has neither the auteur behind the camera, like a Stanley Kubrick or a Fritz Lang, nor the spectacular action in front of it, like an Alien or a Star Wars. Above all, its hyperbolic depiction of squalor and exploitation — for which it has come into criticism — pushes it just this side of kitsch. Yet a more subtle film simply would not have made the mark it has on our cultural memory, much the same way that The Terminator and The Matrix crystalize our fears regarding artificial intelligence more effectively than thinkpieces about the impact of ChatGPT on higher education.

Of course, one might argue that any prescience on the part of Soylent Green is qualified by its getting the larger Malthusian argument wrong. But beneath this material issue lies a deeper philosophical fear: that faced with external constraints, technocratic modernity will find instrumental uses for people, whether they want that or not. In this sense, the film retains a certain queasy power not in spite but because of its ridiculousness, its willingness to make explicit our otherwise tacit horror of turning human beings into mere matter — in this case, literally.

This is to say that Soylent Green may remain kitsch, but kitsch can sometimes express widespread hopes and fears more clearly than great art. And its particular fears concerning the appropriate size and equality of our population are arguably perennial ones, for every human society must reckon with them in some measure. Beneath these fears lies the question of whether our ever more utilitarian modern society has transformed humanity itself into something merely instrumental.

It is on this point that Soylent Green passes the test of the novelist Jessamyn West: “Fiction reveals truths that reality obscures.” For this is the film’s most disturbing takeaway: We did not in the end require a crisis to resort to many of its most troubling practices. We did that anyway.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?