In 1844, a Nashville gentleman named Return Jonathan Meigs was placidly reading Francis Bacon in the evening when he suddenly slammed the book shut and, in the presence of his startled fourteen-year-old son, declared, “This man Bacon wrote the works of Shakespeare.”

A few years later, the American writer Joseph C. Hart, in his book The Romance of Yachting and à propos of absolutely nothing — amidst ruminations on a voyage to Spain, and after a section about bullfighting — announced his belief that Shakespeare was just a copyist in a theater, a name assigned to the plays almost at random. “The enquiry will be, who were the able literary men who wrote the dramas imputed to him?” Hart wrote.

What’s curious about the idea that Shakespeare didn’t write his plays is that, for over two hundred years after his death, there was barely a whiff of rumor that anyone other than Shakespeare had written them, and then, around 1850, there was something in the water, and several people, completely independently, came to the same novel conclusion: Francis Bacon, the statesman, man of letters, and founder of modern science, was the literary genius behind Hamlet and King Lear, The Tempest and Henry V, and all the rest.

Sometime around 1845, the idea got ahold of Delia Bacon, a writer and lecturer living at the time in New Haven, Connecticut. She was not related to Francis, though it is hard to believe that the coincidence of their names didn’t mean something to her. The “monomania” — her term — about Shakespeare actually being Francis Bacon consumed the rest of Delia’s life, much to the consternation of everybody around her. She died in a lunatic asylum, and from that day to this her theory has been considered crackpot. But for Delia it was irresistible, and for her more perceptive admirers there was a method behind the madness.

What her theory was really about was not just the narrow question of the plays’ authorship. It was a whole method of interpretation. On the one hand, she perceived in the plays a deeply embedded, subversive political message — an advocacy for republican, humanist values to combat the tyrannical regimes of Queen Elizabeth and King James I. If that seems extravagant, it anticipates a now well-established field of Shakespeare studies that interprets the plays in very much that light. And, on the other hand, she saw in the plays a stern warning from the 1600s to her own time, the plays admonishing against technocratic materialism, which she called a “‘broken science’ that has no end of ends.” That’s the scientific and technological trend often called “Baconianism,” but, in Delia’s interpretation, Francis Bacon was the avowed enemy of this trend, and the plays his means of transcending it.

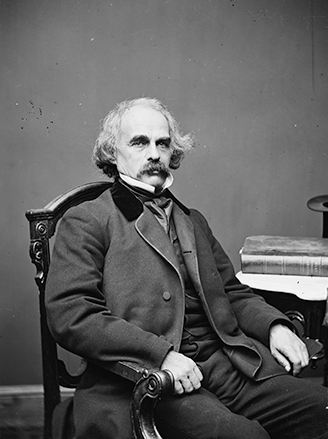

As a writer, Delia could be her own worst enemy. She was prolix, self-contradictory, often incoherent — to grapple with her sometimes requires the same sort of imaginative leaps she applied to the texts she was studying. But a murderers’ row of great writers — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thomas Carlyle, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, and others — saw in her wild vision a coruscating critique of the materialism that was ascendent by the mid-nineteenth century. And even if they often had trouble understanding her, and never took her authorship theory too literally, they seemed to recognize that she was on to something: the compelling idea that the engine of modern history had been set in motion sometime around 1600, that Francis Bacon’s scientific project was at the center of it, and that by a sort of deft intellectual reorientation it might be possible to move oneself out of the grip of a dehumanizing materialism and into a more humane mode of approaching the world.

The basics of Delia’s authorship theory are that Francis Bacon was the guiding spirit for the plays, presiding over a collective effort that included Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser, and maybe also Sir Philip Sidney, Edward Earl of Oxford, Thomas Lord Buckhurst, and Henry Lord Paget — like an Elizabethan literary super-group. The concealment of their authorship of the plays was necessary because of the tyranny of the English crown. In Delia’s view, the plays were essentially republican and rebellious. That rebellion occurred openly in the Earl of Essex’s clumsy uprising against Queen Elizabeth in 1601. When he was beheaded, and the group abandoned overt political methods, the sole form of their opposition was to conceal republican, humanist themes in the plays handed off to William Shakespeare, the manager of the Blackfriars and Globe Theatres and thus a convenient front, as a means of instruction to future generations. “They experienced many defeats…. It did not abate their ardour. They did not strain one nerve the less for that,” Delia wrote of the group, which she called the “Round Table.” “Driven from one field, they showed themselves in another. Driven from the open field, they fought in secret.”

It is easy enough, in a sense, to say that Shakespeare wasn’t really Shakespeare; lots of other people have made that point. The more complicated, and more daring, claim is to say that Francis Bacon wasn’t really the Francis Bacon we know. Bacon has been, for many, either the great hero or the great villain of modernity, or both. He is Faust, he is the sorcerer’s apprentice, he gave up the soul of classical and medieval philosophy and the unifying vision that bound humans to nature, for the sake of gaining knowledge of nature’s secrets and, with that, the power to subject nature to our will. The whole modern trajectory of materialistic thought — science and technology not just as efforts to diminish human needs but as ends in themselves, with deeper human longings subordinated to the notion of “progress” — is, to a startling degree, an extension of his philosophy. To merge together Bacon’s scientific determinism and Shakespeare’s exuberant humanism would, as Delia’s ally Emerson wrote in his first letter to her, “take alchemy itself.” Delia’s totally lunatic, totally fascinating conception was to do exactly that, to make the case that those were two sides of the same coin.

Even Delia’s most learned friends and supporters had trouble pinning down the logic of her argument, but, to take a stab at finding its core idea, it is that Francis Bacon was too brilliant to not perceive that his “new science” was headed toward some sort of dystopia, a tyranny of efficiency, a subjugation of the individual to the needs of a new technocratic state governed by a scientific elite. He recognized this as an inevitability — the genie out of the bottle, a spirit that would be impossible to resist — but which he attempted to intercept somewhere out in the distant future, like a superhero speeding after a runaway train.

In defense of the true Francis Bacon, Delia wrote in her 1857 work The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded:

The Leader of ages that are yet to be … declines to be held any longer responsible for the blind, demoniacal, irrational spirit, that would seize on his great instrument of science, and wrest it from its nobler object and intent, and debase it into the mere tool of the senses; the tool of a materialism more base and sordid than any that the world has ever known…. This ‘broken science’ that has no end of ends, this godless science, this railway learning that travels with restless, ever quickening speed, no whither…. Call it science, if you will, … call it philosophy if you will, … but call it not, he says, — call it not henceforth ‘Baconian.’

Bacon’s reckless science, furnishing tools too powerful to control, is, Delia argues, not really Bacon’s at all; it is a distortion. And, in Delia’s construct, Bacon’s correction to this distorted vision was, wildly enough, “Shakespeare’s” plays — the new science leavened by the inestimable worth, the infinite capaciousness of the individual human.

Discarding Delia’s hypothesis of the authorship of the plays, as most people do, usually means discarding her entirely. But this is a mistake. She had, as Hawthorne, her greatest champion, wrote, “acquired some of the privileges of an inspired person and a prophetess.” Those privileges entail a certain forgiveness on our part for factual missteps, and demand from us a dogged attempt to discern whether the big picture conveys a certain difficult truth. Delia felt acutely, prophetically, that something had gone very wrong in the march of history, and her whole Shakespeare theory, while interesting in its own right, is best understood as part of a larger philosophical and political argument.

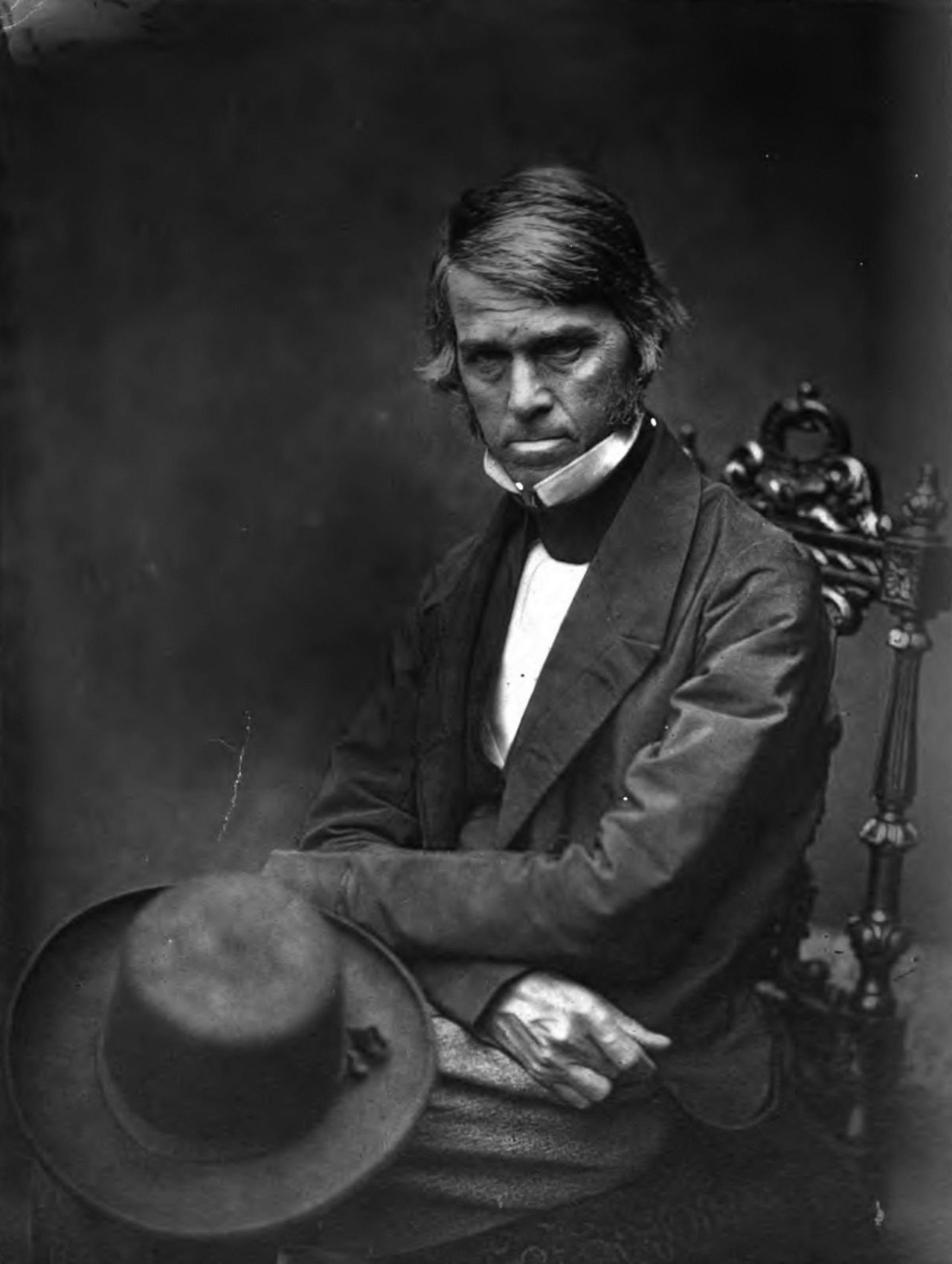

Delia Bacon (1811–1859) was, by all accounts, an extraordinary person. Emerson, who figures prominently in her story, wrote of her that she had “high claims on me and on all of us who love genius and elevation of character.” Whitman called her “the sweetest, eloquentest, grandest woman, I think, that America has so far produced.” A pupil of hers, Sarah Henshaw, recalled, “Delia Bacon was a woman of a genius rare and incomparable. Wherever she went, there walked a queen in the realm of mind.”

Delia’s father was a Congregationalist minister who attempted to found a new community in the wilds of Ohio. The enterprise left him broke, he returned to Connecticut, and died shortly afterward, in 1817, leaving his wife and children. “By what management or magic this young widow … contrived to feed and clothe her six children and herself; to supply them all with the highest education and culture … no one now living can tell,” wrote Theodore Bacon, Delia’s nephew, in his invaluable Delia Bacon: A Biographical Sketch. Delia became a star pupil of Catharine Beecher, older sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, at the Hartford Female Seminary. If she were to list “the most gifted minds” she has ever known, Beecher wrote, among the top would be “the homeless daughter of that western home missionary…. She was preeminently one who would be pointed out as a genius; and one, too, so exuberant and unregulated as to demand constant pruning and restraint.”

For most of her adult life, Delia was a writer and a freelance lecturer on history and literature. A short story of hers once defeated five of Edgar Allan Poe’s in a literary competition, but her work was in the dead end of the James Fenimore Cooper style: stories of the American frontier written in high-flown bathetic language. Poe seems to have had the last word, writing about a play of Delia’s, published anonymously, that its “prose stands sadly in need of a straight jacket.”

As a lecturer, she had a steady following across New England, teaching women — and, on occasion, mixed company, which was very rare for the time. Her older brother Leonard had become pastor of the First Congregational Church in New Haven, one of the leading pulpits in America. This is partly why Delia, as her nephew wrote, “had certain marked advantages of acquaintance and introduction” in New Haven, and her lectures and the salon that had developed around her “included beyond doubt all that was most refined and cultivated in the society of that university town.” One of her listeners recalled, “She was at first a little embarrassed, but soon became so engaged in recommending the study of history to all present, that she ceased to think of herself, and then she became eloquent…. I used to be reminded by her of Raphael’s sibyls, and she often spoke like an oracle.”

But her fame derived also from another plot point in her life. While in New Haven, she had what some called a “Platonic flirtation” with Alexander MacWhorter, who was in training to become a minister. Improbably enough, this became a national scandal. MacWhorter was a brilliant and amoral character, who, as Catharine Beecher scoldingly wrote, “enjoyed wit and humor to an unusual degree.” He seemed obsessed with Delia, stared after her in a hotel dining room, inching closer to her throughout meals, and eventually followed her to Vermont, where she had gone to take a water cure. Their connection was deep — they were both captivated by literature, and, while steeped in Christian teaching, pushed strenuously at the boundaries of conventional thought.

Their publicly undefined friendship became the subject of considerable college town gossip. To ward off scandal, Delia’s friends let it be known that the two were in fact engaged, which MacWhorter would categorically deny, while nastily mocking Delia behind her back. Delia’s brother Leonard, who had appointed himself as her protector, considered MacWhorter “two thirds villain and the other third fool.” Outraged at his ungentlemanly behavior and his insults against his sister, Leonard arranged a clerical trial. Letters were read out loud, Delia was forced to testify before a court of about two dozen ministers, and the scandal spread so far that, wrote Catharine Beecher, “Not only through New England and the eastern cities, but in Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Illinois, Wisconsin and Iowa, the same topic continually recurred as a matter of curious inquiry or accidental remark. There was no escape from it.”

For Delia, a staggeringly proud person, everything about this must have been mortifying. She withdrew from her lecturing career and devoted herself entirely, obsessively, to her theory that Shakespeare was not the author of his plays. She presented it to Emerson, then reigning as the dean of American intellectual life, who was surprisingly encouraging. In 1853, brandishing various letters of introduction from him, she set off for England to obtain proofs for her theory.

The introductory letters Emerson gave to Delia included one to the principal librarian of the British Museum, but that stayed unused; Delia had decided that she wouldn’t go rummaging through libraries or old manor houses in search of physical evidence, that instead she could find everything she needed by staying in her rooms in London and closely reading the plays themselves.

That decision pretty much ended her chance at offering a credible alternative theory of who wrote Shakespeare’s plays, and her interlocutors were accordingly livid with her. “Of course we instantly require your proofs,” Emerson howled across the Atlantic. “If you can find in that mass of English records … any document tending to confirm your Shakespeare theory, it will be worth all the reasoning in the world,” wrote Thomas Carlyle, who became a friend. But she had no capacity for archival research and, as tended to be lost even on some of her admirers, the authorship question truly was secondary for her compared to what she called the “system of practical philosophy” that she uncovered within the plays.

She did employ a letter from Emerson to meet Carlyle, who was so shocked when he first heard her theory that he shrieked — “You could have heard him a mile,” Delia wrote. And her path in England crossed that of other notable literary and political figures, including Hawthorne (who was at the time the American consul in England), Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Richard Monckton Milnes, James Spedding (the editor of Francis Bacon’s works), and soon-to-be U.S. president James Buchanan. “Had not that one engrossing idea possessed her, she might have had a brilliant career among the literary society of London,” wrote Eliza Farrar, an author of children’s books and a Delia admirer.

But Delia had no interest in a brilliant social career. She was actively withdrawing from the world. She had worked out a favorable deal with her lodging-house keeper, who was charmed by her and at some point simply stopped asking for rent — an indulgence that Delia regarded as a miracle “equal to Elijah and his raven, and Daniel in the lions’ den” — and she managed to stretch out the funds intended for her first year all the way through a second.

Feeling confident about her financial situation, she wrote to Emerson in 1854:

So I do not trouble myself about it, and am as happy as the day is long, and only wish I lived in Herschel or Jupiter or some of those larger worlds, where it would not be time to go to bed just as one gets fairly awake, and begins to be in earnest a little…. It has been a year of sunshine with me; the harvest of many years of toil and weeping. I cannot tell you what pleasures I have had here…. My work has ceased to be burdensome to me; I find in it a rest such as no one else can ever know, I think, except in heaven.

But, not too shockingly, the exuberance of writing collapsed with publication. Emerson arranged to have an article of hers published in Putnam’s Monthly, a prominent magazine that would later be folded into the Atlantic. The article, which appeared in 1856 and suffered from Delia’s weakness for orotundity, was widely denounced. John Churton Collins, an English literary scholar, called her a “silly hysterical fanatic.” Richard Grant White, probably America’s most distinguished Shakespearean, wrote, as he later recalled, to Putnam’s, “As the writer was plainly neither a fool nor an ignoramus, she must be insane; not a maniac, but what boys call ‘loony.’”

Emerson lost faith in Delia with the response to the article, whose editor — likely in response to White’s note — pulled a series of chapters of Delia’s book that had been slated for publication and sent them back to Emerson’s while he was away. When Emerson sought to retrieve them, he discovered that a relative had lost them en route — and Delia didn’t have any copies. Hawthorne, who proved to be the most constant and useful of Delia’s champions, helped her to publish her book, The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded — supplying a preface and, quietly, funds. But the book had even less success than the Putnam’s article. In an essay on Delia, “Recollections of a Gifted Woman,” that Hawthorne published in the Atlantic after her death, he wrote, “Miss Bacon thrust the whole bulk of inspiration and nonsense into the press in a lump, and there tumbled out a ponderous octavo volume, which fell with a dead thump at the feet of the public, and has never been picked up.”

By the time publication was arranged, Delia had sunk into deep poverty, and her sanity had become precarious. Eliza Farrar wrote of a visit that Delia made to Farrar’s family in London: “The stranger’s dress was such an extraordinary dishabille that nothing but her ladylike manners and conversation could have convinced the family that she was the person whom she pretended to be.” In a heartbreaking letter Delia sent to Hawthorne, who had planned to visit her, she wrote:

The reason I shrink from seeing any one now is, that I used to be somebody, and whenever I meet a stranger I am troubled with a dim reminiscence of the fact, whereas now I am nothing but this work, and don’t wish to be…. I have lived for three years as much alone with God and the dead as if I had been a departed spirit. And I don’t wish to return to the world. I shrink with horror from the thought of it. This is an abnormal state, you see, but I am perfectly harmless, and if you will let me know when you are coming I will put on one of the dresses I used to wear the last time I made my appearance in the world, and try to look as much like a survivor as the circumstances will permit.

She had, as it turned out, taken to heart her interlocutors’ demands for proof but conceived of that differently from visits to the British Museum. Based on hints that she felt she had discovered in the plays and in Bacon’s writing, she believed she could find decisive evidence buried in Shakespeare’s grave. In 1856, she decamped to Stratford, and was once again fortunate in her interaction with drivers and lodging-house keepers, depositing herself at the home of a woman who had only just thought of taking in a boarder. “Such deathly, deathly weakness no one ever felt before I believe who was able to go about in person to take lodgings,” she wrote to Hawthorne’s wife, Sophia — and, as soon as Delia settled on a price, the keeper, she wrote, “made me lie down on the sofa and covered me up like a mother.”

As soon as she had recovered, she paid a visit to the Church of the Holy Trinity, inside which Shakespeare is buried beneath a stone bearing an ominous inscription:

Good friend for Jesus sake forbeare,

To dig the dust enclosed here.

Blessed be the man that spares these stones,

And cursed be he that moves my bones.

Undeterred, she procured a key from the clerk of the church to visit it at night. Carrying a lantern “like Guy Fawkes,” as she later recounted to Hawthorne, and “some other articles which might have been considered suspicious,” she remained there for long hours, working up the courage to remove the stone. “That was the chance that I had desired, but I had made a promise to the clerk that I would not do the least thing for which he could be called in question,” she wrote, “and though I went far enough to see that the examination I had proposed to make, could be made, leaving all exactly as I found it, it could not be made at that time, nor under those conditions.” Eventually, the clerk, who had been watching the entire time from the rafters, revealed himself and ended her vigil.

“About this time it was that a strange sort of weariness seems to have fallen upon her,” wrote Hawthorne in “Recollections of a Gifted Woman,” his somewhat fictionalized version of this episode. She spent more time in Stratford, continuing to “haunt the church like a ghost,” as Hawthorne put it, but never actually attempted to lift the stone. Not long after, she was admitted to what Theodore Bacon called “an excellent private asylum for a small number of insane persons” near Stratford. “Notwithstanding intermittent lifting of the cloud which had settled about her,” Theodore wrote, “it became more and more evident that the cloud was the darkness of night.” Unlucky in everything else, she at least had good fortune in nephews — Theodore proved to be a first-rate custodian of her legacy and, just at this moment, Leonard’s son George passed through England on his return from sailing near China and released Delia from the asylum. Back in Hartford, though, she was committed to a “retreat” and died the next year, in 1859. As Theodore wrote, with relief, “In these solemn hours of final parting, what some have thought the great delusion of her life was neither spoken of nor thought of.”

If Delia has any enduring legacy, it is the pride of place she earned as the first person to fully articulate an alternate theory of the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. This theory would go on to have a whole life of its own — and in a direction very different from what Delia had in mind. The canonical version of the theory really stems from William Henry Smith, who in 1856 — just after the publication of Delia’s Putnam’s article but apparently completely unaware of it — wrote a pamphlet called “Was Lord Bacon the Author of Shakespeare’s Plays?” Smith’s version of the authorship hypothesis was steeped in upper-class snobbery. The underlying premise of the argument was that Shakespeare, as an uneducated commoner, could not possibly have written the plays, and all the court scenes, battle scenes, and so forth must have been written by somebody who was familiar with courts and battles. The argument misses the possibility that writers can use their imagination, and it turns on very fusty biographical analysis, much of it anchored on some perception of what the plays’ author should have been like. “The history of Bacon is just such as we would have drawn of Shakespeare, if we had been required to depict him from the internal evidence of his works,” wrote Smith. “His daily walk, letters, and conversation, constitute the beau ideal of such a man as we might suppose the author of these plays to have been.”

The popularity of the idea that Shakespeare was really Bacon peaked around the turn of the twentieth century and attracted some famous adherents, such as Mark Twain, who in earlier years as a steamboat pilot had whiled away hours discussing the theory. Sigmund Freud also toyed with the idea. Helen Keller defended it. Ignatius Donnelly, modern founder of the Lost Continent of Atlantis theory and most unlikely of American Congressmen, detected a Baconian cipher in the plays. Orville Ward Owen, a Detroit surgeon and Donnelly disciple, constructed an enormous cipher wheel that showed related passages in the works of Bacon and many others, and claimed that Bacon was actually the illegitimate son of Queen Elizabeth, and that the plays were Bacon’s personal story. Owen’s assistant Elizabeth Wells Gallup uncovered a rival cipher involving alternating fonts that revealed, through meticulous cryptography, other plays hidden inside the texts of Shakespeare’s plays — and, for a time, Owen and Gallup made newspaper headlines for their dueling expeditions to England in search of lost manuscripts, Gallup attempting to move aside secret panels in Bacon’s residence in Islington, Owen purchasing dredging machinery to uncover the manuscripts at the bottom of the Severn River.

All of this was so fun — and, apparently, even led to some genuine breakthroughs in the art of cryptography and contributed ultimately to the deciphering of Japanese military codes during World War II — that it seemed a shame to stop at Francis Bacon, and new generations of amateurs began proposing fresh authors for the plays: the poet and statesman Fulke Greville, Christopher Marlowe (having faked his death), the seventeenth Earl of Oxford (writing partly from beyond the grave), Queen Elizabeth herself, and so on.

But this was all rather far afield from Delia’s animating passion, which was less about solving a historical mystery — though there was that too — than it was about understanding the movement of history itself and understanding the plays not only as political theater but as political philosophy. This is why she simply didn’t accept the conventional image of Shakespeare as a good old boy, an untutored genius. The few extant anecdotes of his life had been cobbled together, in patriotic fashion, to depict a rustic English lad, poaching deer in the Stratford woods, moving to London to evade local authorities, working as a horse-boy and holding the reins of aristocrats’ horses as their owners watched plays, and then picking up playwriting without ever losing his country cunning or playfulness — and as soon as he’d said what he had to say in theater, he retired wealthy to Stratford and soon died from overeating and overdrinking. Delia would have none of that. She insisted on an author who was politically engaged, who was fundamentally serious, connected to broader historical currents.

Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro, whose 2010 book Contested Will deals with the authorship question, wrote that Delia was over a century ahead of her time in seeing Shakespeare’s plays as both collaborative and as politically radical, and that “had she limited her argument to these points … there is little doubt that, instead of being dismissed as a crank and a madwoman, she would be hailed today as a precursor of the ‘New Historicists’” — the scholars who, beginning in the 1980s, sought to read Shakespeare as inextricably tied up with the era’s culture and politics.

But she didn’t limit herself to those points. As she wrote, using one of her favorite epithets for the Bard, it was time “to send the old Player about his business, to make way for this graver performance.”

There had always been an air of dark magic around Francis Bacon, a sense of somebody with secrets. He was from a noble family. His father had been Lord Chancellor in the early part of Queen Elizabeth’s reign before falling into disfavor. His mother was considered one of the most educated women of the time, competent in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, and Italian. His brother went on to become a notable spy, including for the Queen. Bacon started his studies at Cambridge at age twelve — Queen Elizabeth herself recognized him as unusually precocious and serious-minded, calling him “the young Lord Keeper.”

He could be extremely inscrutable — developed ciphers, changed his handwriting, and wrote fictitious correspondence. He somehow balanced his famous writing of essays and developing of a new form of scientific inquiry with a career at court, was a formidable jurist, and rose to be Attorney General and then Lord Chancellor under King James I, before suffering disgrace on charges of corruption. He died, according to one much-repeated account, as a result of conducting an experiment to preserve meat. Some have associated Bacon with the Freemasons and Rosicrucians, and although it is still very unclear how much truth there is in that, he does seem to have been involved with esoteric modes of thought. A century after his death, Alexander Pope summarized Bacon’s ambivalent legacy by calling him “the wisest, brightest, meanest of mankind.”

But by the mid-nineteenth century, Bacon was ascendant. His career at court, along with the scandals that accompanied it, had faded into the background and he came to be widely seen as the founder of modern science and the great benefactor of mankind. In an influential essay in 1837, British historian and politician Thomas Macaulay wrote:

Ask a follower of Bacon what the new philosophy … has effected for mankind, and his answer is ready; “It has lengthened life; it has mitigated pain; it has extinguished diseases; it has increased the fertility of the soil; it has given new securities to the mariner; it has furnished new arms to the warrior…. These are but a part of its fruits, and of its first fruits.”

William Hepworth Dixon, a biographer, wrote in 1861:

The obligations of the world to Bacon are of a kind which cannot be overlooked. Every man who rides in a train, who sends a telegram, who follows a steam-plough, who sits in an easy chair, who crosses the Channel or the Atlantic, who eats a good dinner, who enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something.

To his admirers in the Industrial Age, what Bacon really represented was a philosophical turning point — the Platonic and Christian conceptions that preceded him had aimed at transcendence, at salvation; Bacon instead directed his aim at the practical, at the amelioration of material want.

Macaulay wrote:

To sum up the whole, we should say that the aim of the Platonic philosophy was to exalt man into a god. The aim of the Baconian philosophy was to provide man with what he requires while he continues to be man. The aim of the Platonic philosophy was to raise us far above vulgar wants. The aim of the Baconian philosophy was to supply our vulgar wants. The former aim was noble; but the latter was attainable.

Plato drew a good bow … aimed at the stars; …. but it struck nothing….

Bacon fixed his eyes on a mark which was placed on the earth, and within bow-shot, and hit it in the white.

Delia Bacon was more cautionary. She shared in the nineteenth-century exuberance about the “new science,” which she felt was necessary to rectify the damage done by the unworldly Platonic conceptions: “Two thousand years of barren science, of wordy speculation, of vain theory,” she wrote, “two thousand years of blind, empirical, unsuccessful groping in all the fields of human practice.” But she wasn’t as seduced as some of her contemporaries by the rosy picture of modern science and technology as unalloyed goods. “What are these? — these new orders, — these new species of nature, defying nature, that we are generating with our arts here now?” she asked. “Look at this pale lengthening widening train of their victims. We must look at it. It will never go by till we do.”

To our own ears, Macaulay’s inclusion of “new arms to the warrior” in the catalog of progress sounds off-key — but, of course, this was written a long time before the Somme or Hiroshima. Delia was not so easily taken in. She seemed to sense that history, propelled by the “materialism” of the so-called Baconian science, was headed for potential disaster.

All through her writing, there is a kind of premonition of totalitarianism, and one cannot easily put one’s finger on how exactly Delia ties this thread to that of modern science. This much is clear: she railed both at the absolutist direction of politics and at the “railway learning” of unrestrained science. She didn’t have the benefit of hindsight we have of seeing their connection — in the twentieth century’s totalitarian regimes and in our own century’s tech dystopia — but she seemed, gropingly and intuitively, to spot them in the distance.

Delia saw the beginnings of modern absolutist tendencies in the sixteenth-century monarchies, for example in the Tudors’ use of public terror. She wrote of that regime: “Unchecked by council of any kind, the pure arbitrary absolute will, the pure idiosyncrasy, the crowned demon of the lawless, irrational will, unchained and armed with the sword of the common might, and clothed with the divinity of the common right; … this was a conquest … which left only one nation of slaves and bondmen.”

This conviction that Queen Elizabeth’s regime represented the advent of a new sort of despotism is so out of keeping with the Masterpiece Theater version we have of this time — of Judi Dench or Cate Blanchett as tough, admirable Elizabeth — that anybody who has encountered this part of Delia’s theory tends to dismiss it on this basis alone. She “exaggerates the brutality of the Tudor and Stuart regimes” is the crisp rebuke of James Shapiro, the Shakespeare professor. And, as is her way, Delia tends to offer assertions rather than careful scholarly weighing of the evidence.

But there is room to at least explore her version of the history of the Tudor and Stuart era. “Does not all the world know that scholars, men of reverence, men of world-wide renown, men of every accomplishment were tortured, and mutilated, and hung, and beheaded, in both these two reigns?” she writes — which is a fair point. And the brutality of these regimes would not have seemed so exaggerated to Walter Raleigh, who spent thirteen years in prison and was eventually beheaded, or to Thomas Kyd, who was tortured on the rack, or to Christopher Marlowe, who likely was murdered by Elizabeth’s secret police — or to anyone in the corridors of power for whom a wrong step meant the block.

If Delia’s grim vision of the Tudor and Stuart regimes still seems out of touch, consider that she was not alone. Many decades after her, Hilaire Belloc offered a similar, if more practical, critique. Writing in The Servile State (1912), he described Henry VIII’s seizure of monastic wealth as an “artificial revolution of the most violent kind” that irreparably broke apart England’s delicate economic framework. The crown became sovereign to a degree that was unprecedented in the early modern era, and, to assert its control, relied on a handful of families who enriched themselves enormously through graft and who in return were steadfastly loyal to the crown, creating a new economic system that was a kind of streamlined protection racket and that to a great extent became the model for governance (as per Thomas Hobbes) from that day to this.

And there were of course many critics during the time of those regimes themselves. There was a diaspora of English Catholics across Europe, fleeing the Protestant crown, and their writings leave “a very different narrative, one that sparked with anger and resentment,” as the historian Stephen Alford writes in The Watchers: A Secret History of the Reign of Elizabeth I, a book that explores the “darker and more disturbing world” of that so-called golden age.

If that narrative has largely been buried in history, it is partly because the Tudor regime had mastered several new and invaluable arts — the art of state terror, the art of propaganda, and the art of the secret services that it employed in what historian Keith Thomas has described as a “draconian policy of counter-terrorism.” In the Anglo-centric, pro-Protestant history that has survived to this day, the brutality of that era has come to seem quaint and almost charming — Henry VIII’s summary method of seeking closure for a failed marriage, the Geoffrey Rush character cooling off his burning feet in Shakespeare in Love, the enduring celebration of the vicious torture and execution of Guy Fawkes.

But, for Delia, that state terror was the central fact of the Tudor and Stuart regimes. Employing a startling analogy, she writes, “Does any one think that a universal slavery could be fastened on the inhabitants of this island … without so much as the project of an ‘under-ground rail-way’ being suggested for the relief of its victims?” Quoting the Duke of Gloucester in King Lear, she illustrates the escape route: “I have received a letter this night. It is dangerous to be spoken.” A book like Charles Nicholl’s The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe teases out the habit of the era’s writers of concealing double and triple meanings in their correspondence. While conventional history would hold that Francis Bacon was a loyal servant of the crown, it is not a big stretch to believe that in a world so rife with intrigue he would have had a multifaceted stance toward royal power, and that he would have resorted to the kinds of elaborate subterfuge Delia describes to keep secret his personal convictions.

The pivotal event of Bacon’s career — and the hinge for Delia’s assemblage of characters — was the Earl of Essex’s rebellion in 1601. In standard English history, this is usually treated as a lovers’ quarrel featuring swords and executioners’ blocks — the queen dumping her lover the Earl of Essex, and Essex attempting a coup in reprisal — and it’s considered a piquant detail that, the night before the coup, some of the rebels commissioned a command performance of Shakespeare’s Richard II at the Globe Theatre as a means of psyching themselves up for the revolt.

In Delia’s version, that picturesque rebellion was actually a historical watershed: The group that centered around Essex, “the prophetic and more nobly gifted minds of a new and nobler race of men,” intuited the direction of statist tyranny under Elizabeth and attempted a rebellion along republican, humanist lines. That was the one moment when the “Round Table” openly showed its hand, and when the pieces of Delia’s hypothesis all fall into place. The circle around Essex included the Earl of Southampton (who has come down to us primarily as Shakespeare’s patron) as well as Francis Bacon, who had been Essex’s next-door neighbor when the two were children growing up in London. A play of “Shakespeare’s,” Richard II, was employed as revolutionary agitprop against Elizabeth’s regime. The rebellion failed; Essex was duly executed, Southampton sentenced to death (but then commuted to life in prison and released after just two years); the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, who had performed the play, were questioned about its commission. Francis Bacon was associated with Essex’s party but had kept clear of the rebellion, and when he had an opportunity to serve as one of the prosecutors against Essex he did so with alacrity, brushing aside the defendant’s excuses, helping to ensure not only his conviction but his execution.

Even for admirers of Francis Bacon’s philosophy, this episode — the vigorous prosecution of his own friend — has been a black mark against him. “He did more than a person who had never seen Essex would have been justified in doing,” wrote Thomas Macaulay. “He employed all the art of an advocate in order to make the prisoner’s conduct appear more inexcusable and more dangerous to the state than it really had been.” Macaulay’s reluctant conclusion was that “the moral qualities of Bacon were not of a high order.”

Delia interpreted Bacon’s conduct completely differently. In her view, everyone in Essex’s coterie carried out his allotted role. Bacon was “a man of art,” she wrote — and he used the opportunity of Essex’s trial to regain royal favor and to secure necessary concealment for his own revolutionary inclinations. Meanwhile, Essex, who knew that he was doomed to die, did not betray his prosecutor’s cover.

With Essex’s rebellion broken, subversion, in Delia’s telling, continued in the form of plays — and the light-hearted literary style of the “Round Table,” the popular plays that had been spirited to the Lord Chamberlain’s Men during the 1590s, began to deepen and darken, to take on increasingly greater political and philosophical import. Francis Bacon, in a safer but still perilous position at court, churned out his essays and philosophical treatises attempting to establish a rational and scientific understanding of the world (the “Baconianism” that has come down to us). But his views on politics and human relations were too incendiary for direct formulation and so were spoken by theatrical characters and buried under layers of meaning. In this conception, the plays of “Shakespeare” were the promised and never-written fourth part of Bacon’s grand philosophical scheme, the Great Instauration, the part that was intended to deal with human affairs — very much like the technique in spy movies where a photograph is ripped in half and given to two accomplices, and a full understanding of a situation can be attained only once the separated halves are reunited.

The bulk of Delia’s writing turns on close readings of “Shakespeare’s” plays with this system in mind — that the plays, particularly Richard II, Henry V, Julius Caesar, Coriolanus, Hamlet, King Lear, and The Tempest, are suffused at once with a spirit of exploration in keeping with Francis Bacon’s scientific disposition and with a humanistic impulse valorizing naturalness, the infinite human soul, the capacity to resist tyranny and social coercion in whatever guise they may take.

The best example she brings to make her case is the “Harry in the night” scene in Henry V. It really is a radical scene, in which the king — just before the Battle of Agincourt, the acme of English monarchical patriotism — suddenly has a crisis of conscience about the principle of monarchy in general. “I think the king is but a man, as I am,” King Henry says, while in disguise, to his soldiers, and the soldiers pick up the cue and reply with a blistering assault on feudal hierarchy. “It is a conversation in which a party of common soldiers are permitted to ‘speak their minds freely’ for once,” writes Delia, “in a tone as free as the president of a Peace Society could use to-day in discussing the same topic, intermingling their remarks with criticisms on the government.” Any of these sentiments voiced directly — in an era in which the “divine right of kings” was becoming gospel — would be treasonous, but they were permissible as the momentary waverings of a fictionalized king, the grumblings of theatrical stock characters; and the author of the play, hiding the true import of the scene, was careful to end the debate with a rather specious argument defending monarchical prerogatives. A more perceptive reader, claims Delia (in a move that anticipates the interpretive techniques of Leo Strauss), would note that King Henry’s concluding point does not really mean what it seems to mean on the surface but “shows, indeed, that there is but one ultimate sovereignty; one to which the king and his subjects are alike amenable, … from whose violated laws there is no escape.”

In other words, beneath all the kings and feudal dramas that populate “Shakespeare’s” plays, there actually was an abiding case for egalitarianism that was centuries ahead of its time. “The State is composed throughout … of individual men, social units, clothed of nature with the same faculties and essential human dignities and susceptibilities to good and evil, and crowned of nature with the common sovereignty of reason, … elected of nature to that dignity,” Delia wrote of the politics implicit in the plays. Taken together, the plays propounded “a human civilization” utterly distinct from the “rudest ages of social experiment” — the template of modern autocracy that was then in gestation at the Tudor court.

By this point in Delia’s theory, she has created a very particular image of Francis Bacon — the shrewd jurist climbing the greasy pole at court, while, in secrecy and poetry, subverting the entire principle of monarchy. Even more fraught than that, though, is her view of the tension between the programmatic science Bacon espoused in his philosophical writings and the humanistic political system he envisioned in the plays. She wrote:

While the Man of Science [Francis Bacon] was yet planning these vast scientific changes … there was another kind of revolution brewing. All that time there was a cloud on his political horizon — “a huge one, a black one” — slowly and steadfastly accumulating … which he had always an eye on…. He knew that so fearful a war-cloud would have to burst, and get overblown, before any chance for those peace operations, … which he was bent on, could be had….

That revolution which “was singing in the wind” then to his ear, was one which would have to come first in the chronological order; but it was easy enough to see that it was not going to be such a one … as a man of his genius would care to be out in with his works.

The benevolent science Bacon was developing would ultimately engender peace, but, before that happens, there would be an extended period in which the new science would be co-opted by a tyrannical political power. Already in Bacon’s time, Delia wrote, “England cowered and crouched, in blind servility, at the foot of that terrible, but unrecognised embodiment of its own power, armed out of its own armoury, with the weapons that were turned against it.” And, in Delia’s conception, Bacon knew that that sort of technocratic autocracy would continue for maybe centuries to come, generating “new combinations” with technological progress serving only the powerful.

Bacon had no interest in being part of those developments. So he wrote his scientific works in a politically neutral way — although knowing that his efficient method for generating knowledge-as-power would tend to be manipulated by the powers that be. And then he concealed his political critique within the plays. “The suppressed Elizabethan Reformers and Innovators were men so far in advance of their time,” Delia wrote of Bacon and his accomplices, “that they were compelled to play this great game in secret, in their own time, referring themselves to posthumous effects for the explanation of their designs.” It would fall to the distant future — to Delia’s own time, if not later centuries — to understand the true vision of the plays, that the new science was meant ultimately to be subordinate to the human soul and not the other way around.

The truth is that Delia’s case for Bacon’s authorship of the plays is based primarily on intuition and some very light circumstantial evidence. “The fact that these two great branches of the modern philosophy [Shakespeare and Bacon] make their appearance in history at the same moment, … this is the fact that strikes the eye at the first glance at this inquiry,” she writes. And that is a fair point, if not exactly persuasive evidence — it is a remarkable coincidence that Shakespeare and Bacon, two of the most deeply influential men of letters in modernity, happened to live in the same city at the same time and to have had a number of friends in common. “What more natural than to suppose that these two philosophers, these men of a learning so exactly equal, might have some sympathy with each other, might like to meet each other,” Delia continued — concluding that the most natural explanation was that a meeting wasn’t necessary. They were the same person.

After Delia’s death, some pieces of evidence emerged that made her wild conjecture more compelling than might have been expected. Francis Bacon was affiliated with a law association named Gray’s Inn, which sometimes also put on plays, for at least one of which Bacon had been called “chief contriver.” Around 1900, scholars poring over the Pension Book of Gray’s Inn, a financial record of the society, noted that a new play we know as one of Shakespeare’s, The Comedy of Errors, had been performed there on December 28, 1594. It’s unclear, however, who the players were, because we also know from royal records that on the same night Shakespeare and his Lord Chamberlain’s Men were performing for the Queen elsewhere in the city. Various theories have been proposed: about errors in the dates, about an accidental double-booking, or about Gray’s Inn making a joke. It’s an odd, intriguing event, and the cleanest, and most heretical, explanation is that Gray’s Inn, rather than the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, was the creative force behind the production — which connects Francis Bacon closely to a play in the Shakespeare canon.

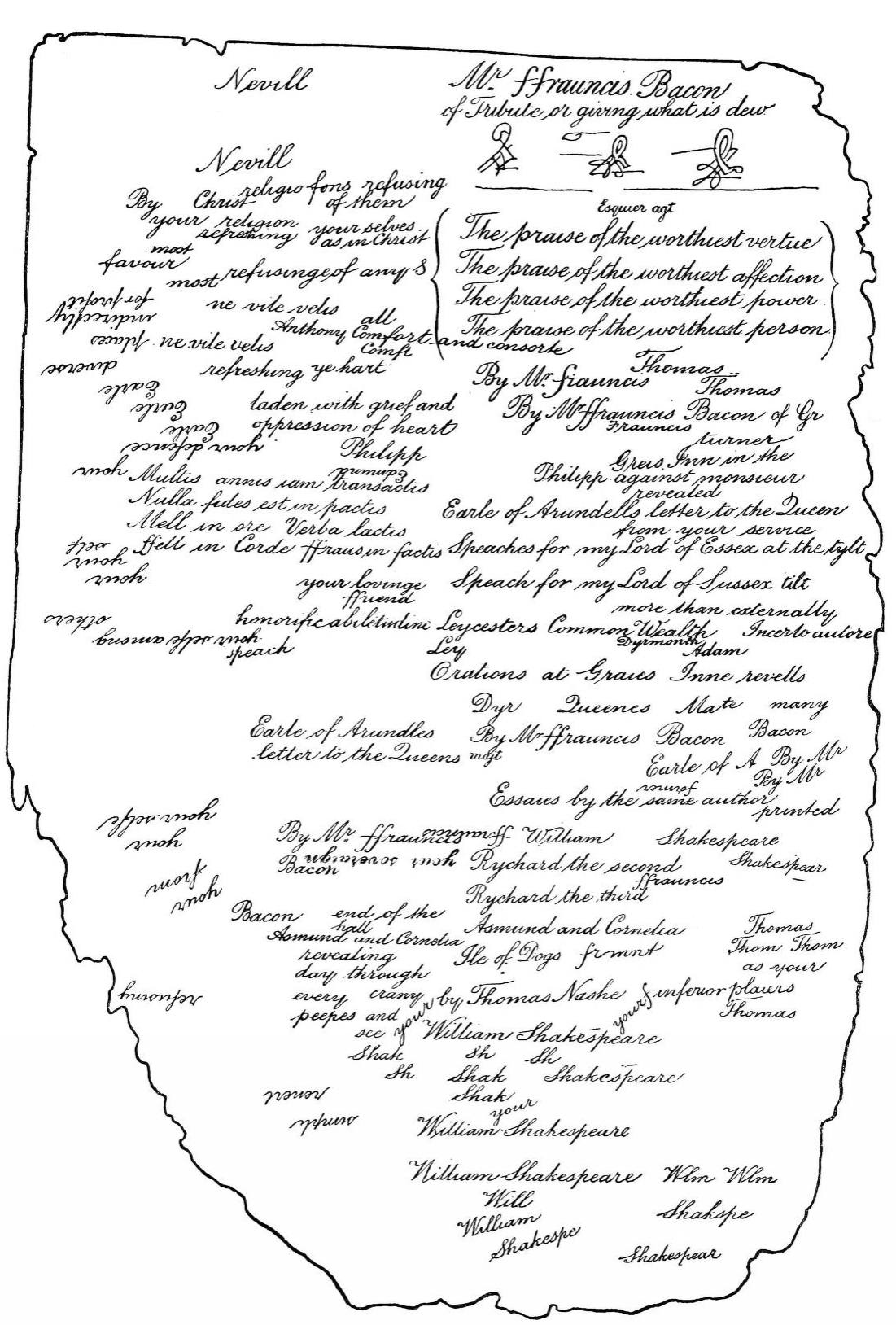

The most remarkable piece of evidence for the authorship theory emerged in 1867, when a folder of fire-scorched papers was discovered in Northumberland House, next door to where Bacon lived for a time. The folder dates from the late 1500s and contains a curious cover page: Scribbled across it, in handwriting identified to be that of a scribe employed by Bacon, are a number of names, including those of Francis Bacon and William Shakespeare. It also has the unusual word “honorificabiletudine,” which may be a version of the even stranger word “honorificabilitudinitatibus” that makes an appearance in Love’s Labour’s Lost. The page also shows a partial table of contents for the manuscripts inside the folder, featuring the titles of several of Bacon’s published essays and the Shakespeare plays Richard II and Richard III, in addition to a play by another Elizabethan playwright, Thomas Nashe. On the backside of this cover page is the note “put into type.” It’s very hard to know what to make of all this, but a perfectly straightforward explanation would be that Bacon, or a secretary of his, was doodling out names of his various alter egos, writing down phrases that appeared in his plays, and then the note “put into type” was telling an assistant to tear away the manuscripts that had once been attached to the folder and to deliver them to a print house. Everything about this scene is exactly as Delia Bacon would have pictured it: Bacon as puppet master not only for Shakespeare but for a writer like Nashe as well.

And then there are some other odd facts. As noted earlier, the followers of Essex and Southampton had commissioned the performance of Richard II as if it were part of their revolutionary politics. The poet and playwright Ben Jonson, a contemporary of Bacon, made various statements praising him for his poetic mastery, calling him “the mark and acme of our language,” even though Bacon had certainly not been known for his poetry. In the same passage, Jonson describes Bacon as having “performed that in our tongue which may be compared or preferred either to insolent Greece or haughty Rome” — the very same phrase Jonson used to praise Shakespeare:

Leave thee alone for the comparison

Of all that insolent Greece or haughty Rome

Furthermore — and this is a perplexing detail for the orthodox theory of Shakespeare authorship — there were several plays that appeared in the 1590s and the early 1600s with the name “William Shakespeare” or the initials “W.S.” proudly on the cover, which have been deemed to be of inferior quality and kept out of the canon. The most natural explanation for how A Yorkshire Tragedy, The London Prodigal, or Thomas Lord Cromwell came initially to be attributed to Shakespeare is that the name served as a kind of clearinghouse for playwrights who, for whatever reason, wished to remain anonymous; Alexander Pope compared it to the practice of giving “Strays to the Lord of the Manor.”

Taken together, all these pieces of evidence push Delia’s theory away from lunacy and closer to plausibility. Add to this the fact that Delia’s idea that the plays are rich in hidden meanings and emotions aligns perfectly well with orthodox interpretations of Shakespeare: Keats wrote about Shakespeare’s “negative capability,” his being at home with doubt and mystery; Virginia Woolf wrote of Shakespeare’s mind as being “androgynous,” in tune with both sexes; and legendary Shakespeare director Peter Brook has spoken of the “secret play,” the one that isn’t directly in the text. The preponderance of double meanings, the widely-observed lack of biographical information about the author — all of this makes sense if the plays were written collaboratively, focused on universal themes, and if the secret of their authorship were a matter of life and death. Delia’s theory strikes similar chords as Harold Bloom’s “invention of the human” — the idea that, in Shakespeare for the first time, consciousness became three-dimensional, people started to see themselves not as unitary figures primarily occupying social and moral roles but as split selves, like in a hall of mirrors, a view that corresponds with the mask-like method of composition Delia perceived in the plays. And if it seems outlandish that the plays should be written in this way — collaboratively by a group of aristocrats working in secret, designed to send coded messages about history and science to future generations — well, consider that the plays are different, and better, than any others; and maybe it’s that kindred spirit among their authors and the intensity of the circumstances of their composition that gave them their charge as well as their profoundly enigmatic character.

If Delia’s theory were right, if Francis Bacon really was the primary author of the plays of Shakespeare — as well as writing his copious scientific and philosophical works, as well as keeping his day job at court, eventually as Lord Chancellor, as well as being an influential jurist — then he would be the genius of geniuses and his 4-D chess game for countering his own theories of scientific progressivism would contain just about anything that anybody needed to know about modernity. “To add all these [the plays] to what Lord Bacon has avowedly done is, to make him such a prodigy as the world never before saw,” wrote Sophia Hawthorne, an early convert to Delia’s theory, in astonishment.

In reading Francis Bacon with an eye open to stylistic similarities between him and the author of “Shakespeare’s” plays, this much seems clear: Bacon was obviously a brilliant person with a far-ranging intellect, and his essays were crisp and witty, but — with no disrespect intended to Return Jonathan Meigs — I have the opposite reaction to his: Shakespeare and Bacon just strike me as two different people. “New Atlantis,” for instance, Bacon’s one attributed foray into fiction, was woodenly written, and there are a couple of poems of Bacon’s that we know of — one begins “The world’s a bubble; and the life of man less than a span” — that have nothing in common with “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

Also, in recent years, a more rounded depiction of Shakespeare has finally emerged from historians. Gone is the deer-stealer, the rustic unlettered genius, and, in that place, is a recognizable type: an ambitious young creative moving to the big city, having the luck to come across a dynamic circle of artists developing new forms, and having a unique, capacious talent that seemed to imbibe all the major currents of his time.

In the end, I don’t buy the story of Bacon as Shakespeare. But, curiously, I find that discarding it doesn’t take away from Delia’s accomplishment. Her interlocutors, despite their misgivings about the absence of hard proof, came to feel the same way. “And when, not many months after the outward failure of her lifelong object, she passed into the better world,” wrote Nathaniel Hawthorne in his touching tribute, “I know not why we should hesitate to believe that the immortal poet may have met her on the threshold and led her in, reassuring her with friendly and comfortable words, and thanking her (yet with a smile of gentle humor in his eyes at the thought of certain mistaken speculations) for having interpreted him to mankind so well.” Emerson, sounding a bit like a racing tout, wrote in 1857 that “Our wild Whitman, with real inspiration but choked by Titanic abdomen, & Delia Bacon, with genius, but mad, & clinging like a tortoise to English soil, are the sole producers that America has yielded in ten years.”

There was something else about Delia that spoke to me — her conviction. Throughout her letters, I’d be struck by the imbalance between Delia and her interlocutors. Her champions were all very impressive people in their own right, and all as sympathetic as they could be, given their very understandable skepticism, and they all come across as deeply constricted — most of all in the politeness and modest demurrals that saturated their correspondence: “I very rarely get so far from home, where I am detained by a truly ridiculous complication of cobwebs” (Emerson); “Will you kindly dispense with the ceremony of being called on (by sickly people, in this hot weather)” (Carlyle); “I am bothered and bored, and harassed and torn in pieces, by a thousand items of daily business” (Hawthorne). Meanwhile, Delia was like the life force itself, ineluctable. And everybody around her, other than her brother Leonard, who was meddlesome to the last, seemed to recognize the impossibility of dissuading her from her path. “I have not in my life seen anything so tragically quixotic as her Shakespeare enterprise; alas, alas, there can be nothing but sorrow, toil, and utter disappointment in it for her!” wrote Carlyle — before concluding, “she must try the matter to the end, and charitable souls must further her so far.”

At the time that I encountered Delia, this struck me as the right attitude to writing, to any sort of meaningful endeavor — that you had to wrench it out of yourself, no matter how absurd it might seem to others. I was twenty-eight, stuck in my life, stuck above all in my writing — my default had been to write personally and I was just sick of myself. It had somehow been suggested to me that I write a scene or monologue about Delia, which seemed to be obviously unpromising material. The alternative authorship theories for the plays struck me as an incredibly creaky, nerdy conspiracy theory. But, as I dug through her letters, the scene or monologue started to turn, to my amazement, into a full play. I’d feel that I was getting somewhere when I’d read over a passage and couldn’t figure out which parts of it were mine and which were Delia’s. I remember, as I approached the end, getting so excited that I drove to a coffee shop — feeling that there was less possibility of distraction there — and, after years of false starts, dead ends, a morass of Word files, was almost shaking from nervousness to get to the last lines and actually finish something.

For me, that turned out to be the push. After that, these play and story fragments cluttering my laptop unspooled themselves and, one by one, became finished pieces. And the difference was, really, a very simple shift — a not-caring, a not-worrying if something was good or bad, right or wrong, a sense of following some inner star wherever it led.

Delia had put this very well, in a letter to Emerson:

This study is so very absorbing, and it consigns me to such complete solitude, that I find all my progress in it is made at a most ruinous expense to my life and health…. My only consolation is that I cannot help it. The choice is not mine.

And writing to Emerson again a few years later:

To go on with it, calmly and patiently, to work away at it, day after day, and year after year, as if it were the merest piece of ordinary drudgery, and without sympathy or counsel, that is what I have had to do, and what I thought I never could do at first.

In a way that is hard to describe but matters to me more than almost anything, I give Delia credit for getting me unstuck. But I wasn’t just interested in Delia for the sake of self-help or writing advice: I really felt that, in her muddy, maddening way, she was on to something with her philosophy. And in the last few years, as the coils of technocracy and “Baconianism” have gotten noticeably tighter, I’ve come increasingly to see her as prescient. Writing in the era of Hegel’s dialectics, Comte’s positivism, and Macaulay’s Whig history, she can be forgiven a certain confusion about the meaning of “progress.” Her version of Francis Bacon is even messier than I’m presenting it, as a man sometimes working for scientific progressivism and sometimes against it. But she never submitted to exuberant, naïve narratives depicting technological advancement as someday erasing toil or misery, just as she never bailed out into anti-modernism à la Rousseau, seeking a return to nature or pre-modern simplicity.

What she represented was a synthesis characteristic of the more visionary figures of the period around 1850 — of Whitman, Emerson, Baudelaire, and Poe, the first generation to recognize modernity for what it was, a distinctly new reality. In his prose poem Eureka, Poe unleashed a similar attack on blind faith in a system of progress, in Baconianism — or, what he mockingly called “the Hog-ian philosophy.” Whitman, for his part, articulated a very delicate relationship to modernity, on the one hand welcoming technology and the propulsive dynamics of the modern city, on the other fundamentally rejecting the eschatological vision of ever-unfolding material progress.

More than any of the others, Delia wrestled these developments back to the source — to a schism that occurred in Western thought around 1600. The unworldly Platonic, medieval conception was, by common consent of innovative thinkers of the period, discreetly dropped — and its place taken by a new belief system that was more earthy and pragmatic. But the new system need not have been the one that gradually took shape: scientific progress as social progress, the subordination of society as a whole to technological and material amelioration, managed, as a matter of course, by increasingly powerful, centralized political and corporate entities. It may sound fanciful to search for the antidote to that entire project in Shakespeare’s plays, but that seemed reasonable to Delia Bacon, as it does to me — that there was some kind of deeper message in Shakespeare, a humanist vision, which, as Delia wrote, was concerned “with all the parts and members of the social state, from the king on his throne to the beggar in his straw,” and whose aim it was “to disclose ultimately, and educate in every member of society that entire and noble form of human nature which ‘each man carries with him.’”

At a moment when “Western” is more and more becoming a dirty word — synonymous with imperialism, Faustian progress, and now the apparently irresistible advent of a digital dystopia — there’s something in Delia Bacon’s Baconian Shakespeare that seems whisperingly to offer a way out, tracing back to a vibrant moment in the Renaissance, with the spiritual and the material beautifully balanced, with science viewed as an instrument and not an inexorable fact, and with a humanistic spirit dueling against the domination of the statist and technocratic.