What ever happened to machines taking over the world? What was once an object of intense concern now seems like a punchline. Take one of the latest videos released by the robotics company Boston Dynamics, of its iconic two- and four-legged machines shaking it to “Do You Love Me?” by The Contours, which was met with sarcastic online quips about the robots doing victory dances after murdering humans. The revolt of the machines, subsumed into the background ambiance of generalized fears of tech dystopia, no longer seems like a distinctive worry. For those who remember an earlier era of techno-panic, that should be startling.

Once upon a time — just a few years ago, actually — it was not uncommon to see headlines about prominent scientists, tech executives, and engineers warning portentously that the revolt of the robots was nigh. The mechanism varied, but the result was always the same: Uncontrollable machine self-improvement would one day overcome humanity. A dismal fate awaited us. We would be lucky to be domesticated as pets kept around for the amusement of superior entities, who could kill us all as easily as we exterminate pests.

Today we fear a different technological threat, one that centers not on machines but other humans. We see ourselves as imperiled by the terrifying social influence unleashed by the Internet in general and social media in particular. We hear warnings that nothing less than our collective ability to perceive reality is at stake, and that if we do not take corrective action we will lose our freedoms and way of life.

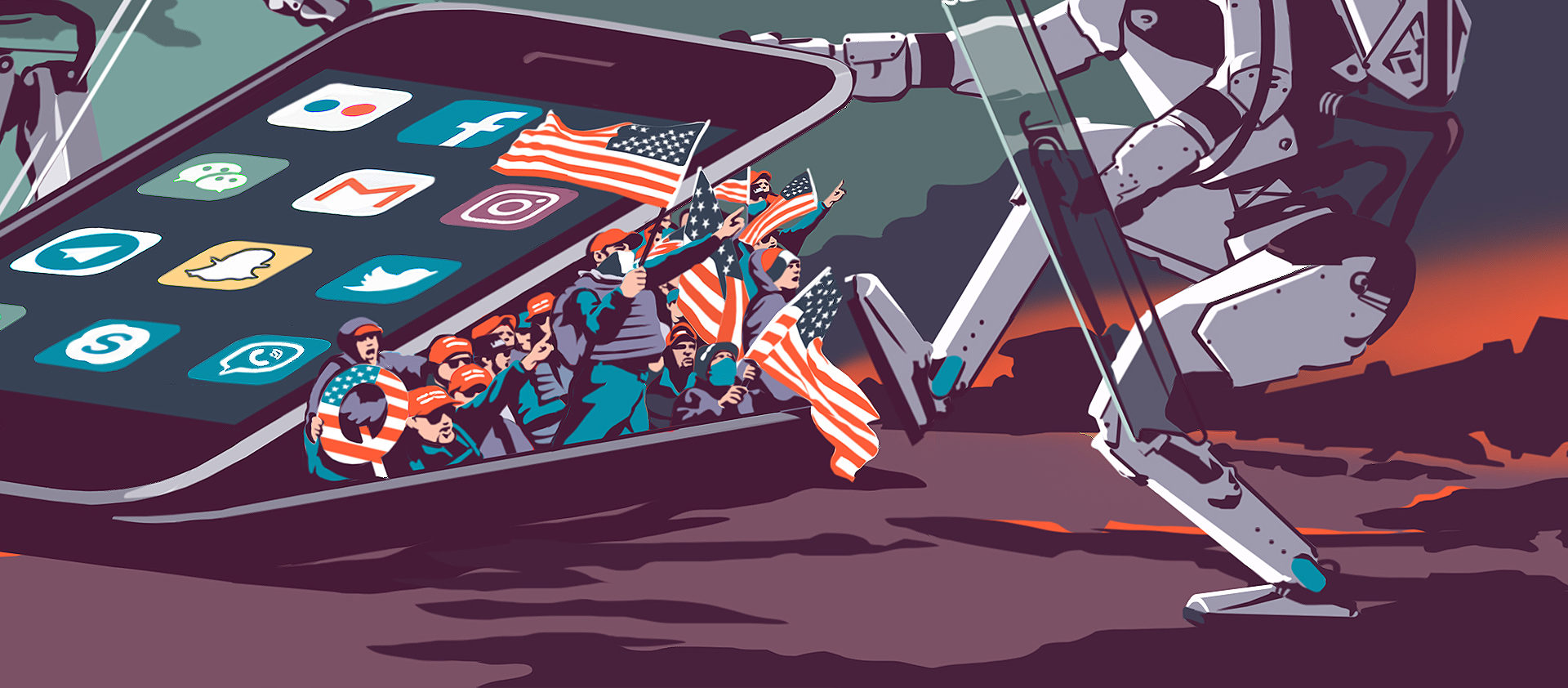

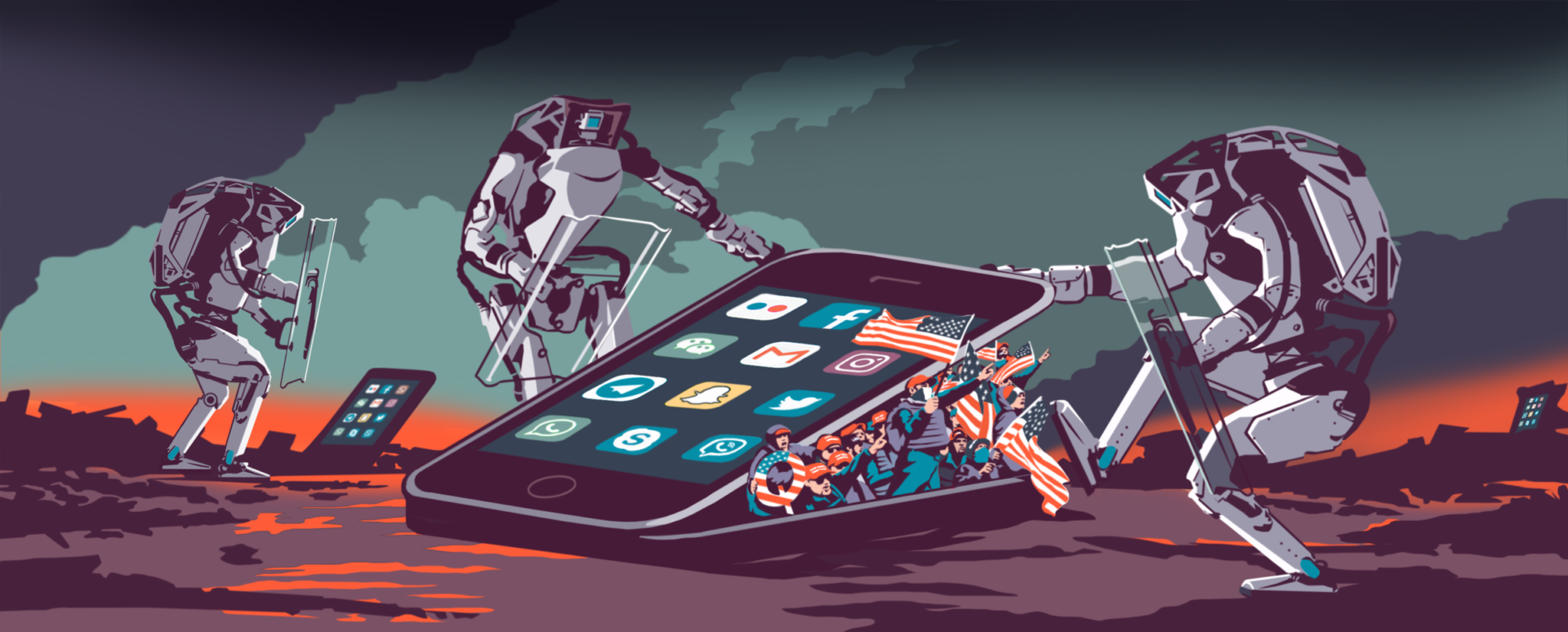

Primal terror of mechanical menace has given way to fear of angry primates posting. Ironically, the roles have reversed. The robots are now humanity’s saviors, suppressing bad human mass behavior online with increasingly sophisticated filtering algorithms. We once obsessed about how to restrain machines we could not predict or control — now we worry about how to use machines to restrain humans we cannot predict or control. But the old problem hasn’t gone away: How do we know whether the machines will do as we wish?

If you had told a lay observer a decade ago that there would be a crisis over Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media platforms banning the president of the United States for inciting a violent riot against Congress that included a barechested, behorned man dressed as the “QAnon Shaman,” you would likely be accused of writing bad science fiction. But this is the platform politics crisis in early 2021.

As Aaron Sibarium recently argued in American Purpose, the event and the responses to it show the paradox of the online digital commons. In the leadup to the January 6 siege of the Capitol, President Trump and his allies could use social media as a coordination mechanism for a motley collection of illiberal forces to mobilize a fierce attack intended to generate a surreal spectacle, disrupt the certification of the presidential election, and assault any politicians unlucky enough to be caught by the mob as it breached the Capitol. But by January 9, Trump and many of his supporters were permanently banned from social media platforms, and Parler, a redoubt for Trumpists among others, had been dropped by Apple and Google app stores and even removed from the Amazon servers that hosted the site. Social media, Sibarium observed, could at once be too lax and too controlling.

But in this sci-fi, the villains raging out of control were not machines but human mobs — albeit mobs bolstered by world-sprawling tech platforms. Instead of a sudden, synchronized human revolt, a conventional science fiction event would have a sudden moment in which machines, without warning, turned on their human overseers. These kinds of scenarios didn’t just crop up in fiction; they also inspired a cottage industry of serious-minded people theorizing about the machine revolt — how it might come about, how it might be averted.

The ground covered in this literature varied widely. Some of it — like Bill Joy warning about self-replicating nanotech machines becoming a “gray goo” that destroys all life, Bill Gates raising the alarm about artificial intelligence overtaking humans, or Elon Musk telling us that we are on the verge of “summoning the demon” — was always ridiculous. The pronouncements of these tech celebrities paralleled a much more convoluted but equally strange and mystifying collection of online subcultures who debated the threat of inevitable machine superiority with the energy usually associated with forum fan-theorizing about Lost.

Ethicist David Leslie, in a 2019 review of a book on machine control, described how these cultures envisioned scenarios such as “an AI system that induces tumours in every human to quickly find an optimal cure for cancer, and a geoengineering robot that asphyxiates humanity to deacidify the oceans.” The common theme was the pathologies of runaway rationality — of machines programmed to achieve a certain end that got out of control. Many of these scenarios circled back to the technological “singularity,” a moment when the intelligence of some machine agent, or a collection of them, suddenly increases exponentially, with unknown consequences for the human race.

It is easy, perhaps too easy, to dismiss all this as crankbait. Tech entrepreneur Maciej Cegłowski argues that this intellectual pursuit is interesting but ultimately barren, a sort of “string theory for programmers.” It allows both academic theorists and members of niche online subcultures to “build crystal palaces of thought, working from first principles, then climb up inside them and pull the ladder up.” At worst, Cegłowski lamented, it stimulates grandiosity and megalomania. Scientists, technologists, and various interested parties became swept up in the belief that they alone had divined a world-ending calamity, that they were charged with finding their own idiosyncratic solutions and imposing them on “non-player characters” (read: the rest of us) who were supposed to just sit back and let the big brains go to work.

However, one could, more charitably, look at some of this literature as a valuable exploration into a far older problem than machine dystopia: the manner in which the road to hell is paved with good intentions. We say we want something, but as we pursue it we often come to realize that it is not at all what we had thought we wanted. The literature on runaway tech highlighted the elusiveness of our “true” desires and whether machines can be made to realize them (more about this in a moment).

Since the 2016 presidential election, fears about machine dystopia do not seem like nearly such a preoccupation. Instead, attention has shifted to online radicalization, misinformation, and harassment. This distinction may seem like two ways of talking about the same thing. After all, many tech critics ultimately place the blame for these online dysfunctions on software that encourages toxic behavior and on companies’ lax moderation policies. Perhaps fear of machine revolt has just morphed into generic fear about out-of-control algorithms that, among other things, fuel hatred, fear, and suspicion online. There is some truth to this, but it also misses important differences.

While online behavior is certainly shaped by platform mechanisms, the fear today is less of the mechanisms themselves than of whom they’re enticing. Prior emphasis on the machine threat warned of the unpredictability of automated behavior and the need for humans to develop policies to control it. Today’s emphasis on the social media terror inverts this, warning of the danger posed by unchecked digital mobs, who must be controlled. The risk comes not from the machines but from ourselves: our vulnerability to deception and manipulation, our need to band together with others to hunt down and accost our adversaries online, our tendency to incite and be incited by violent rhetoric to act out in the physical world, and our collective habit of spiraling down into correlated webs of delusion, insanity, and hatred.

While amenable in theory to fears of machine malevolence, there is no real mechanical equivalent in this picture to the central role played by the runaway machine of old. Actually, the roles of humans and machines have switched: The machines must now restrain the dangerous humans.

Large armies of underpaid — and often psychologically traumatized — human content-moderators wading through massive quantities of digitized records of man’s inhumanity to man are not enough. The only thing capable of handling the job of managing the online commons at scale is massive automated systems that filter content, delete it, and otherwise modify it to enforce platform policies. Reliance on mechanical moderation always reflected a mixture of reasonable pragmatism and unreasonable optimism about the ability of machines to handle the nuances of human language and social interaction. It also showed the desire of tech companies to find a way to deal with the toxic behaviors generated by their platforms without fundamentally altering their product or business models.

Automated moderation of content was never without criticism. Outsiders from across the political spectrum argued that it was opaque, unaccountable, and provided at best a fig leaf of liberal proceduralism. It was an attempt to pass off a robotic version of “rule by law” as “rule of law.” But the criticism was drowned out by even louder demands since 2016 to crack down harder on online misinformation and extremism.

These demands reached a crescendo between early 2020 and early 2021 — between the start of the pandemic and the Capitol attack. The massive expansion of automated rule-enforcement changed the nature of online speech. As Harvard lecturer Evelyn Douek observed in a widely cited legal paper,

platforms cracked down on misinformation in an unprecedented fashion because the harms were judged to be especially great, and they did so while acknowledging there would be higher error rates than normal because the costs of moderating inadequately were less than the costs of not moderating at all.

The governance of content moderation online has now become a matter of which machine errors are to be preferred and what level of machine error is acceptable. At scale, perhaps, all machine ethics simply becomes a matter of probability. Instead of deliberating over the balance of goods at stake in allowing or restricting a particular post, moderation debates now assume that significant error and inconsistency are inherent hazards of the platforms and merely ask if the errors are going in the right direction.

The growing intellectual consensus is that a vulnerable public must be protected from having their minds hijacked by dangerous online memes. An ugly and messy struggle for control over online communication looms. Fears of machine revolt have faded, but the very machines that were once seen as future tyrants — automated systems — must now save humans from themselves.

The shift away from the fear of unpredictable robots and toward the fear of chaotic human behavior may have been inevitable. For the problem of controlling the machines was always at heart a problem of human desire — the worry that realizing our desires using automated systems might prove catastrophic. The promised solution (simple enough!) was to rectify human desire. But once we lost optimism about whether this was possible, the stage was set for the problem to be flipped on its head.

The most sophisticated robo-doomsayers observed how machines — and the bureaucracies that controlled them — were capable of acting in ways that evaded prediction and control. Given the power of machines to realize human desires, warnings of robo-doom asked us to carefully consider what those desires really are, the potential consequences of feeding them as inputs into the machine, and whether this would really produce what the human masters intended.

But strangely, mixed with grim contemplation was an optimism about the capacity of humans to rationally deliberate about their desires and how the machines would realize them. This optimism helped to navigate an inherent contradiction in the doomsayers’ ideas: Again, the problem of controlling the machines was at heart a problem of human desire — but human desire was also the solution. Cheap and false desires would bring about machine catastrophe — but wise, pure, and true desires could forestall it. But how can we know which desires are which?

The twentieth-century cyberneticist Norbert Wiener made what was for his time a rather startling argument: The machine may be the final instrument of doom, but humanity may be the ultimate cause. In his 1960 essay “Some Moral and Technical Consequences of Automation,” Wiener recounts tales in which a person makes a wish and gets what was requested but not necessarily what he or she really desired. For example, in the classic “The Monkey’s Paw” by English writer W. W. Jacobs, a man’s wish for 200 pounds is answered by a messenger at the door: The man’s son was killed in a work accident, and the company now sends 200 pounds as consolation. Wiener writes:

Disastrous results are to be expected not merely in the world of fairy tales but in the real world wherever two agencies essentially foreign to each other are coupled in the attempt to achieve a common purpose.

The two parties haven’t communicated sufficiently about what their common purpose is, and therefore the result of the partnership will be poor at best and catastrophic at worst.

How this plays out with social media — both with fomenting anger and with automated content-moderation — comes into focus with what Wiener says next:

If we use, to achieve our purposes, a mechanical agency with whose operation we cannot efficiently interfere once we have started it, because the action is so fast and irrevocable that we have not the data to intervene before the action is complete, then we had better be quite sure that the purpose put into the machine is the purpose which we really desire and not merely a colorful imitation of it.

Wiener was of course not talking about social media, but we can easily see the analogy: It too achieves purposes, like mob frenzy or erroneous post deletions, that its human designers did not actually desire, even though they built the machines in a way that achieves those purposes. Nor does he envision, as in Terminator, a general intelligence that becomes self-aware and nukes everyone. Instead, amid the Cold War, Wiener was writing about the prospect that “learning machines will be used to program the pushing of the button in a new push-button war.” In other words, he imagined a system that humans cannot easily stop and that acts on a misleading substitute for the military objectives humans actually value:

If the rules for victory in a war game do not correspond to what we actually wish for our country, it is more than likely that such a machine may produce a policy which would win a nominal victory on points at the cost of every interest we have at heart, even that of national survival.

Some twenty years later, the film WarGames imagined a military command-and-control system that learned that the only way to win is not to play at all.

But Wiener’s essay was not just about the risks of machine systems. It was about anything — like a bureaucracy or a research community — for which we lack “an effective understanding of many of the stages by which [it] comes to its conclusion and of what the real tactical intentions of many of its operations may be.”

Wiener’s framing proved influential because he generalized it beyond literal human–machine cooperation to any situation in which two systems work together at different temporal and perceptual scales. Because choices made today with limited information can have terrible long-term consequences that cannot be foreseen, Wiener warns that “the purpose put into the machine” — be it a literal machine like a Twitter algorithm, or a metaphorical one like the corporation that runs it — should be the purpose that we “really desire” and not a “colorful imitation.”

This is why Wiener’s essay is broadly familiar to critics of rationalism, not just those who focus on the problem of controlling machines. The frustrating recurrence of partial and often misleading information about human preferences is a dominant theme in their writings about all that can go wrong when human preferences are built into a system. Wiener’s essay also became symbolically important, because it articulated a critique of techno-rationality using the language of techno-rationality, at a time when grand engineering and social-engineering projects were widely expected to solve many of humanity’s most intractable problems — and it came from a scientific celebrity.

There is a risk in Wiener’s distinction between what we desire and what actually happens in the end. It may create a false image of ourselves — an image in which our desires and our behaviors are wholly separable from each other. Instead of examining carefully whether our desires are in fact good, we may simply assume they are, and so blame bad behavior on the messy cooperation between ourselves and the “system.” We believe we have the best intentions — but then something mysterious intervenes between them and their tangible manifestation in the real world.

When robots programmed to realize our desires actually create nightmares, we might do well to interpret this as a discovery that within our desires lurked nightmares all along. Instead of enforcing our intentions more carefully, as Wiener would have us do, we might ask whether our intentions were actually so pure to begin with. On the other hand, it’s a lot more pleasant to avoid asking this — and so we find an out. The mysterious thing that intervenes may not be the machine but simply our own cognitive dissonance.

In the Soviet Union, officials cultivated a cynicism that allowed them to maintain a savvy distance from the consequences of the ideology they saw no future without. Publicly, they pledged allegiance to the state and its guiding maxims. Privately, they were all too aware of the corrupt and incompetent way the ideology was actually realized. Maintaining an artificial separation between the ideology, which was publicly affirmed, and the consequences of it, which were privately denounced, allowed one to simultaneously be a party man and say “I ain’t a sucker.” Something like this was at work too in Wiener’s simultaneous pessimism and optimism about human desire.

The lesson here is this: If we do not recognize our own desires after we see the machines acting to realize them, we may simply be unwilling to reexamine our desires and ask ourselves whether they are truly good. Perhaps this unwillingness leads us to conceive an artificial separation between our real desires — which we can never truly formalize, quantify, and mechanize — and false imitations of them, which we hold responsible for the consequences we find abhorrent.

This separation has helped to estrange us from our desires, transforming them into autonomous forces separate from the meatbags they inhabit. In the calls today for machines to squelch online mobs, we can recognize a descendant of the estrangement we find in Wiener. In his day, he could still treat human desire as the problem — but also the solution to how machines can be controlled. Even though machines realizing our desires in the wrong way can lead to calamity, humans can yet “exert the full strength of our imagination to examine where the full use of our new modalities may lead us.” The pairing of this pessimism and this optimism was too unstable to endure, and would not survive the 2010s.

What do we really desire and how can we know it? Or are we in fact strangers to ourselves? Wiener’s phrase “two agencies essentially foreign to each other” is also how one might describe two aspects of human motivation and behavior: those that can be discerned through conscious introspection and those that cannot. This dichotomy has been a perennial subject of human fascination — and the stock cliché of every romance novel and romcom. If what we consciously want is different from what we unconsciously want, which of these do our actions reflect?

We may believe that we are the origin of our thoughts and actions, but we may instead obey unconscious instinct, sophisticated psychological patterns configured through evolutionary processes, or the inescapable influence of our peers and the societies we live in. If there is even just some truth to this, then in a very real way there is something foreign or strange about us, perhaps something we find uncomfortable or even cause for shame. We may believe we honestly like a work of art because it embodies aesthetic qualities we value. But where did those values really originate? In liking it, are we merely just signaling something desirable about ourselves to our peers? And if some aspect of our behavior is beyond our full knowledge and control, what if — collectively — these behaviors could be combined into something powerful, malicious, and overwhelmingly oppressive?

Now enter social networks. Wiener worried about whether or not we would sacrifice our true desires for cheap mechanical imitations, to our collective peril. But social networks are built on mass imitation — human imitation, yes, but performed on a scale many recognize as mechanical. The signaling to our peers we find so worrisome in another context is the platforms’ core feature. They take the underlying problem of the split between human desire and ultimate behavior implicit in Wiener’s essay and push it to the extreme.

Consider how social networks have systematized mass imitation. Geoff Shullenberger, in a July 2020 Tablet essay on the dynamics of online mobs, shows how social networks remove an underlying constraint on older forms of collective aggression. The hardest part of getting a group to be aggressive is usually the first act of aggression, not because of the cowardly unwillingness to throw the first stone but rather because throwing the first stone is an act without a pre-existing template. Nobody knows in advance exactly what kind of act may become contagious, and at what time.

But social networks provide a template for throwing the first stone: the public-shaming post. With a template for this first act, contagious aggression can piggyback off of the natural human tendency to emulate pre-existing behaviors and attitudes. Not only do social networks make it easier to both generate and replicate mass aggression; they also provide viral fame as a reward for the first person bold enough to throw the first stone. “It’s unsurprising, then, that some users are trying to make a name for themselves on the basis of first-stone throwing,” writes Shullenberger.

Now, mass imitation online may occur even without anyone really knowing who threw the first stone, and perhaps nobody knowingly did. This is one of the ways in which known and hidden desires combine online and produce terrifying mass behaviors of which we cannot clearly say whether anyone really intended them. This is because even when people act out of sincere belief in a particular cause — say, exposing a racially insensitive op-ed — the template for expressing that belief online, for example through public shaming, and for imitating it may dictate the behavior and so escape our control.

The anime TV series Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex coined the term “stand alone complex” for copycat behaviors performed en masse without explicit coordination — by people who all believe themselves to be acting out of individual will and sincere belief in their cause. When asked about their motivations, they may all correctly state their belief in the cause, but they will leave out the manner in which their actions conform to a particular iconic template they imitated. Distressingly, no true originator may be identifiable after the cascade.

The “stand alone complex” illustrates how something very familiar — collective norms, values, and beliefs, for example political convictions — can be transformed by the digital commons into a threatening force alien to human understanding, beyond human control, and ultimately destructive. When we believe ourselves to be taking a righteous action we thought of all on our own, we may suddenly realize we are also in the company of ten thousand others all gripped by the same belief, swept along together in the hivemind frenzy of an outrage mob. Human desires, split off from human understanding and control, become something dangerous and malevolent, perhaps akin to occult forces and witchcraft.

Drawing on the work of Charles Taylor, L. M. Sacasas has argued in these pages (“The Analog City and the Digital City,” Winter 2020) that the emergence of a worldwide digital commons built on globe-spanning communications backbones has led to an inversion of typical assumptions about modernity and the self.

The premodern world was fascinated with “non-human agents” that had the ability to induce or impose meanings independent of our knowledge and control, and to bring about outcomes in the physical world. Premoderns felt themselves to be fundamentally “porous” in nature, unable to prevent the vulnerable self from being impinged upon by spirits and demonic forces. The vulnerable self required refuge within ordered societies that used common rituals and folkways to keep the bad magic at bay. Heresy was dangerous because even a single heretic could throw the safety of the community in doubt by diluting the purity that the rituals were painstakingly intended to maintain.

In contrast, the idealized modern human is — or rather was — autonomous, rational, and secured against outside harmful influences. Key to the emergence of the modern age was the rise of what Taylor calls the “buffered self.” This new self, Sacasas explains, “no longer perceives and believes in sources of meaning outside of the human mind” and is not disturbed by “powers beyond its control.” If the porous self is beset on all sides by harmful external forces, prone to corruption and manipulation from the unseen, and in perpetual need of community protection, the rational and autonomous modern self is confidently able to think and act alone due to its inviolability and stability. Meaning for moderns is only created by individual human minds — the only minds that count. The mind is sealed off from the world, autonomous and self-driven, and unconcerned with matters beyond its control. It is capable of tolerating heresy, because heresy is at best an intellectual error, not a potentially catastrophic event that leads to the compromise of the entire community.

This image of the modern self already began to crumble during the Cold War with the emergence of the forces of technological automation that Norbert Wiener discussed. But in the twenty-first century it has broken entirely. Sacasas argues that in our digital era “certain features of the self in an enchanted world are now re-emerging.” “Digital technologies influence us and exert causal power over our affairs,” and we find ourselves suddenly aware once again of how we operate “within a field of inscrutable forces over which we have little to no control.” These forces are not spirits or demons but rather “bots and opaque algorithmic processes, which alternately and capriciously curse or bless us.” One such force is, of course, Internet memes, and online content generally. Amplified and circulated by complex proprietary information platforms hidden behind corporate obfuscation, and often too complicated even for their own engineers to fully comprehend, these systems make their users vulnerable to external predation by harmful forms of social influence. The common factor in all the fears about rampaging memes is the belief that memes are like magic, with powers to cause real-world effects, akin to the premodern spiritual objects Sacasas describes.

But another way of understanding the power of meme magic is that it represents merely our own distorted perceptions of our split selves and of desires that have become alien to us through social-media imitation. Wiener asked us to check whether our desires were true or merely colorful imitations, but the construction of digital platforms founded on the promise of unrestrained imitation pushed these tensions to the breaking point.

So rather than hoping to rectify human desire and to rein in out-of-control machines, we now worry that out-of-control humans hooked up to machines threaten social stability. If the self in the digital age is indeed once again porous, it must once again take refuge in the comfort and protection of community rituals designed to ward off the spirits and demons of an older and supposedly more primitive world — a world that digital life has brought back. But the role of the community ritualists is now assumed by machines.

The machine-control theorists of old were fixated on the discrepancy between our desires and observable machine behavior. The machine may poorly imitate what the human overseer desires, and the gulf between what is desired and what is done may have lethal consequences. This way of putting the problem requires clarity about what our desires are and how they correspond to what the machines are doing. In the digital environment, we no longer have this clarity, nor do we know what count as true, authentic desires. And so we lose confidence in ourselves as the solution to the original problem and are left only with the burden of knowing that we are the problem — or rather some strange manifestation of ourselves with a tenuous link to our underlying “true” desires and intentions.

It then becomes obvious why the machines are now marshalled into service to rescue us. Much like ritualistic institutions in premodern times, the machines perform the purifying rituals that protect the self and the community from the threatening outside world and its malign forces. They filter and remove information, alter how it spreads, and expel heretical members.

But the software that is designed to protect the community’s helpless members from dangerous information at the very same time maintains their state of helplessness. It operates without transparency and accountability, leaving users perpetually in the dark about when and where it steps in, and forces them to resort to superstitious folk theories about why their social media feeds are what they are at any given moment. And although the machines are intended to serve the public community at large by protecting its members, they work on behalf of entities — social networks — that are not themselves really communities. As Jon Askonas and Ari Schulman explain in a recent National Affairs essay, online speech platforms have “failed to form coherent communities” and therefore lack “the legitimacy to enforce norms of speech.”

As platforms become more universal, less subject to visible control by human moderators, and less comprehensible to individual users, they become increasingly less like communities. The machines that police them are designed to enforce the values the community shares — but they lack the legitimacy of human guardians, who can be held responsible and, if necessary, replaced. The machines are assumed to embody the values the community cherishes and not misleading approximations of them, but the old question about how we know whether machines in fact do so have obviously gone unanswered. The question may not seem as salient as it once did, now that online mobs have replaced machines as bogeyman, but it is no less troublesome. Just because we do not talk much anymore about the problem of how to control autonomous machines does not mean the problem has vanished.

As our lives become more and more dependent on online platforms — especially during a pandemic that limits our in-person communication — the stakes in giving the machines control over our speech and behavior are higher than ever. We have delegated this power to them such that they can protect us from all-too-real harms and safeguard certain liberties, with the assumption that they act in accordance with our fundamental values. But do they really? How do we know? And if it turns out that they are not in fact acting as we truly wish, how do we know, once we have granted them the power to correct our desires, that we will still be able to correct theirs?

The problem of how to control the machines has faded in cultural importance after the utopian promise of social networks became a nightmare, and humans rather than machines became the villains. So now the machines fight against the memes — ironically, for the people who devoted themselves to controlling the machines unwittingly invited them to control us.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?