We spoke with Michael T. Osterholm, professor of environmental health sciences and chair in public health at the University of Minnesota, author of Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs, and a former Science Envoy for Health Security at the U.S. Department of State.

In the Q&A below, Osterholm tells us about the coming “coronavirus winter,” why looking at the pandemic as a single rolling wave is not helpful, his concerns over “mitigation fatigue” from the public, and why the most important goal of increased testing in the United States is to move away from “monolithic recommendations” and toward a more targeted approach.

Osterholm has also written about the coronavirus pandemic for the New York Times and has previously appeared as an interview subject in The New Atlantis (“The Ebola Gamble,” Spring 2015). This interview was conducted by phone yesterday, March 16, and has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The New Atlantis: How serious is this situation? Are we locking things down too early or too late?

Michael Osterholm: This is a very serious situation. We will overwhelm the American health care system. It won’t be equally distributed around the country — some places will get hit much harder than others. We will run out of critical personal protective equipment for health care workers, which will ultimately result in infections that they will acquire on the job.

We will continue to see, I’m afraid, certain political responses which will lead people to challenge public health recommendations on ideological as opposed to scientific grounds.

And we don’t have a sense of how this is going to play out relative to time. I tell people we’re responding to this just like we’re responding to a Minneapolis blizzard, where we’re going to lock down for a couple of days and everything will go back to normal — as opposed to the fact that this is going to be a coronavirus winter and we’re just in the first week or two of a long season. This could last for months.

There doesn’t seem to be a wave hitting yet. In the U.S. we’re not yet seeing the kinds of things we’re seeing in Italy. Is it about to hit?

MO: First of all, it’s not Italy, it’s the Lombardy region. This is not an unusual situation with respiratory pathogens, where we see a rolling set of epidemics that occur in some cases simultaneously, sometimes sequentially, but they over time merge into one big epidemic. We can see seasonal flu where we’ll have hot spots in the U.S. for several weeks in some places, and in other places no activity at all. So I think looking at this as a wave is not helpful, because it’s a collection of smaller, yet very significant outbreaks, that make up that total amount.

It probably takes at least 6 to 8 [transmission] generations before you have enough serious cases that people really pick it up. And we have been right on track with this in terms of number of cases.

In Wuhan, what data we have suggests the virus arrived around the middle of November. Yet it didn’t show up in a measurable way until around Christmastime because of the background of other respiratory illnesses, like influenza. In Seattle, the case came back from Wuhan in the middle of January, and then suddenly in the last week of February, Seattle blows.

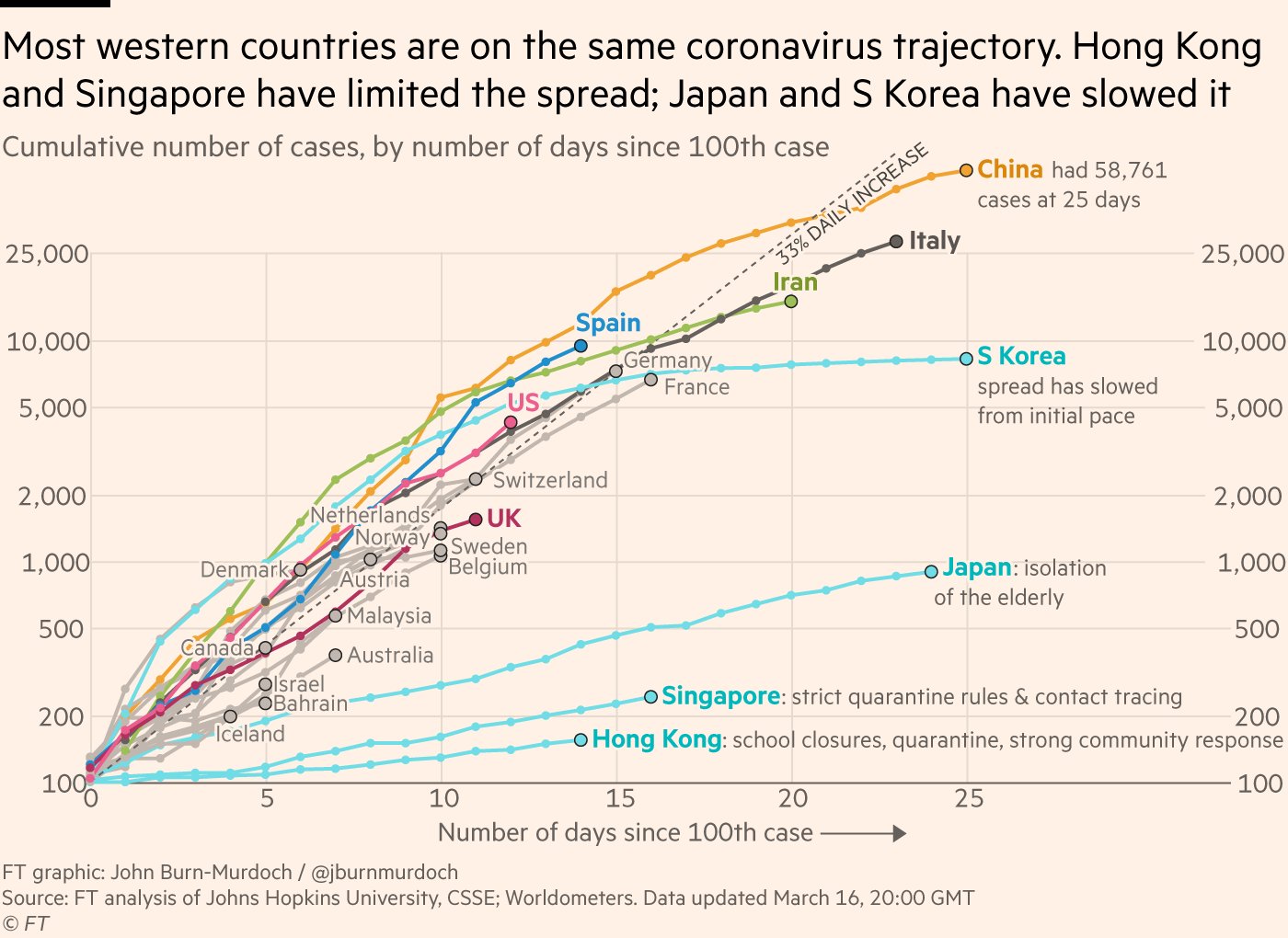

Have you seen the Financial Times graph of the growth of case counts in different countries, which shows that the growth rate in the U.S. is similar to Italy and Spain?

MO: I think a lot of those data are meaningless. It doesn’t really tell you about what’s happening, it tells you about what’s being detected. When you have small numbers, to triple and quadruple them is nothing. It’s all within the margin of testing error, meaning who’s getting tested and who’s not. We have a lot more cases in the United States than our testing would give us the ability to show.

So given that the testing in the United States is still so inadequate, what do we actually look at then, what are the indicators of the progress of the disease?

MO: I think that we will begin to catch up with hospitalizations and intensive care. I think that is really the tip of the iceberg that is exposing what is underneath it. So as goes intensive care bed needs, so goes the epidemic in that area. And deaths also, but deaths are more difficult because it’s almost three weeks of illness before the average patient dies. So you’re going to expect to see the number of fatal cases delayed relative to the actual number of new cases by onset.

Everybody is looking at stats on the number of cases, and for the reasons that you outlined, that seems like an inadequate way to understand the situation.

MO: It is, but it’s the best we have. But we need it to be better. The reason is that the decisions we need to make about mitigation need to be based on just picking up that curve as it starts to spin upwards.

I’ve been very concerned — you know, we know that mitigation fatigue is a big problem. We saw that in 2009 [the swine flu pandemic], people will wear masks or respirators for a couple of weeks, and people just get used to it, and they don’t comply. What I’m concerned about is having one monolithic recommendation in the United States, because we’re in this series of rolling epidemics. And if I say here in Minnesota, “Do this now” and then nothing happens for three weeks, people are going to say, “Wait a minute, what did you make us do?”

On the other hand, you don’t want to get in when your emergency rooms and intensive care units are overwhelmed. You want to be able to get in early and interrupt that. So testing really helps, because you really need to be picking up early cases. Then you really come forward with forcible recommendations, and explain why.

So the main purpose of the testing right now is to figure out where to target the most heavy mitigation measures?

MO: Yeah, yeah. It’s a combination. You want to look at influenza-like illness, and know is it flu or not flu, COVID-19 or not COVID-19. Then next you want to test people who are not anybody’s idea of at-risk. That’s where you’re going to pick up all the totally unsuspecting cases that have had contact with someone that no one knows about.

Then the other piece you want, of course, is the hospital setting. You want to know for sure how many people requiring medical care are infected. You also want to curb any potential sources that could cause transmission in the hospital to health care workers and others. That’s what’s happened on multiple occasions, with MERS and SARS.

What do you make of the uncertainties about re-infection? The UK right now is pursuing a herd immunity strategy, which assumes that people will become immune.

MO: That probably is right. I don’t think we have any evidence that this won’t produce some immunity. At least in the short term, for the next month [after recovery], you’re likely to be immune. I can’t say that with certainty, but when you look at the vigorous immune response we’ve seen, it’s probably there. But this is clearly one of the major questions we have to answer.

The more people we can put into labs who have been infected and recovered and have had natural immunization — that’s going to be really important. The other thing that does is provide the ideal worker. If you’ve already had it and fully recovered, you’re the one that can work in the hospital, health care settings, grocery stores, care for aging parents and not worry about being a source. So we really need to figure out how to deal with recovered individuals, who can really play an important role in responding to this epidemic.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?