On June 9, 2016, a law permitting physician-assisted suicide went into effect in California. The same day, Dr. Lonny Shavelson, an emergency medicine physician, opened the Bay Area End of Life Options clinic to provide the newly legal service.

A longtime activist for the cause, Shavelson’s interest began in adolescence. In an interview last year, he describes how, when he was fourteen, his severely depressed mother “enrolled me in pacts for her death.” Despite acknowledging that her request was “pathological,” he eventually chose to become a doctor “not only to help her in her illness but also to help her die.” In his 1995 book A Chosen Death, Shavelson recounted underground assisted suicides he witnessed. In one case, “Sarah,” the leader of a local advocacy group, took an especially active role when “Gene,” an elderly, partially paralyzed alcoholic man, asked for help with ending his life. But things did not go as planned, when Gene jolted awake in the middle of the process:

“It’s cold,” he screamed, and his good hand flew up to tear off the plastic bag. Sarah’s hand caught Gene’s at the wrist and held it. His body thrust upwards. She pulled his arm away and lay across Gene’s shoulders. Sarah rocked back and forth, pinning him down, her fingers twisting the bag to seal it tight at his neck as she repeated, “The light, Gene, go toward the light.” Gene’s body pushed against Sarah’s. Then he stopped moving.

Shavelson watched, frozen with ambivalence at whether to intervene. He did not.

Shavelson seems to have taken away from this event a sense of the dire need for reliable methods for ending life. Ignorance of these methods, he argued in last year’s interview, was much of what motivated doctors to oppose assisted suicide:

Everybody I talked to said we don’t know how to do this. So we don’t agree with it. And over time, what’s wonderful to watch is how patients have been the leading force…. As [hospices] started getting patient requests, they couldn’t just keep saying no. Hospices are fundamentally a loving and caring and responsive organization.

He and his colleagues have thus made themselves “ambassadors,” training physicians around the state on proper suicide methods to meet patient demand. As of last November, Dr. Shavelson and his staff had been at the bedside of 114 people whose suicides they assisted.

The narrative Dr. Shavelson offers, however — of benighted doctors led into the light of assisted suicide by education and patient demand — ignores the larger story. A closer look at the recent rash of legalization of assisted suicide in several states and countries shows that doctors’ own medical associations actively helped to pave the way, all while ducking behind a disingenuous guise of merely staying neutral. The story is a growing scandal to the profession of medicine. But it is not too late to undo.

In May 2015, the California Medical Association changed its position on physician-assisted suicide from “opposed” to “neutral.” In doing so, it broke from the national organization of which it is a chapter, the American Medical Association, which still maintains its clear opposition. The chapter had been prompted to reconsider its longstanding position by the proposed End of Life Option Act, which, if passed, would permit California physicians to prescribe lethal drugs to terminally ill patients.

The issue of legalizing assisted suicide had been debated several times before in California, and proponents presented no novel arguments this round. But what became apparent was just how little will there was among members of the CMA to push back against arguments in favor of assisted suicide — arguments that more or less amounted to “the times they are a-changin’.” The CMA, like its parent and other state medical associations, is a professional organization that exists primarily to lobby politically for the interests of its physician members, which means that its decisions aim to sway lawmakers and the public.

To explain the change in the CMA’s position on assisted suicide, spokeswoman Molly Weedn told the press that the debate within the organization was prompted by a “shift in the conversation” on the issue among both the American public and doctors. She defended the neutral position by suggesting that it “allows physicians to determine between themselves and patients whether they want to participate in the End of Life Option Act.” She also mentioned the political consideration that dropping its opposition would enable the CMA to have input on the legislation, for example to ensure that a provision be added that doctors need not participate in assisted suicide if they choose not to. (It should be noted that assisted suicide, or enabling suicide by providing lethal drugs and information about dosage, is distinct from euthanasia, which refers to the act of directly administering the drug to a patient.)

The irony seemed lost on Weedn that the need for conscience protections from the law probably would not have arisen if the association had maintained its opposition in the first place. It was the CMA’s switch from opposition to neutrality that helped provide California lawmakers the political cover they needed to legalize assisted suicide.

The bill that prompted the association’s debate, modeled after Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, initially stalled in a committee. But the bill then passed during a special session, ostensibly called to deal with a shortfall in the state Medicaid budget, and aided by smaller committees stacked with proponents. In October 2015, it was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown.

Medical associations’ positions on assisted suicide in other states and at the national level have been mixed. In 1994, the Oregon Medical Association decided to take a neutral position on a state ballot initiative to legalize assisted suicide, and it narrowly succeeded at the polls. But when a decision to repeal the law came on the ballot three years later, the association supported the repeal. That initiative failed and assisted suicide has remained legal in the state ever since. The OMA maintained incoherent positions on the issue for years, stating that it was neutral on the question of assisted suicide, but opposed to the statute legalizing it. The association finally dropped its formal opposition to the law in 2017.

In the wake of California’s legalization of assisted suicide, the Colorado Medical Society went neutral in 2016, and a ballot initiative legalizing the practice was approved thereafter. Likewise, the Medical Society of the District of Columbia took a neutral position on a bill that would go on to legalize assisted suicide in 2016. Most recently, in April of this year, a bill to legalize assisted suicide in Maine prompted the state medical society to change its position to neutral. Maine passed the bill into law in June. In contrast to associations that adopted neutrality prior to state legalization, the Vermont Medical Society went neutral in 2017, four years after the practice was legalized in the state. New Jersey recently legalized assisted suicide despite opposition from the Medical Society of New Jersey, which, in its meeting this May, narrowly voted to maintain its opposition to the practice.

Several other state medical societies have adopted neutral positions in the past few years despite legislation permitting assisted suicide having so far failed in their states, including the state associations of Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Nevada. New bills continue to be introduced every year, and proponents understand that these bills will have a much stronger case for passage if state medical societies first get on board. And if the examples of Oregon, California, Colorado, and Washington, D.C. are any indication, it appears that many state medical societies may be prepared to acquiesce.

At the national level, the last few years have likewise seen intense efforts aimed at changing the American Medical Association’s longstanding opposition to assisted suicide. Its official position is as follows:

Permitting physicians to engage in assisted suicide would ultimately cause more harm than good.

Physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks.

But recently, it became uncertain whether the AMA would stick with this position. Last year, the Oregon delegation put forward a resolution asking the association to reconsider its position. The proposal was referred to the AMA ethics committee, the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, which recommended maintaining the AMA’s opposition to physician-assisted suicide. However, apparently aiming at a kind of compromise, the ethics council’s report avoided explicitly stating that the practice constitutes unethical behavior:

The council recognized that supporters and opponents share a fundamental commitment to values of care, compassion, respect, and dignity, but diverge in drawing different moral conclusions from those underlying values in equally good faith.

The issue remained unsettled until just before this article went to press: In June, an overwhelming majority (360 to 190) of AMA delegates voted to adopt the report and an even larger majority (392 to 162) reaffirmed the association’s current position — that “physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer.” The vote also effectively endorsed the report’s finding that the term “physician-assisted suicide” should continue to be used instead of “aid in dying” or “death with dignity.”

Likewise, the American College of Physicians — a professional association of internists and the second largest medical association in the United States after the AMA — reaffirmed its opposition to legalizing assisted suicide in an elegantly reasoned 2017 position paper. The ACP concluded:

This practice [assisted suicide] is problematic given the nature of the patient–physician relationship, affects trust in that relationship as well as in the profession, and fundamentally alters the medical profession’s role in society. Furthermore, the principles at stake in this debate also underlie medicine’s responsibilities on other issues and the physician’s duty to provide care based on clinical judgment, evidence, and ethics. Control over the manner and timing of a person’s death has not been and should not be a goal of medicine.

By contrast, among the groups pressing the AMA to reconsider its opposition has been the American Academy of Family Physicians, which has rejected the term “assisted suicide” in favor of “medical aid in dying.” Departing from the AMA and ACP stances, the AAFP adopted a policy that “medical aid in dying” is an “ethical, personal” option for terminally ill patients capable of making an informed decision. By remaining officially neutral on state bills attempting to legalize assisted suicide, while providing support and advice to physician members who want to practice it, the AAFP manages to characterize its explicit moral licensure of assisted suicide as a “position of engaged neutrality.”

While the AMA has for now decided to retain its opposition to assisted suicide, its counterpart in Canada provides an instructive case in how federal policy can shift when a national medical association changes its position on the issue.

In August 2014, the Canadian Medical Association abandoned its longstanding policy that doctors should not participate in assisted suicide and euthanasia. The move came shortly before the Supreme Court of Canada decided to hear a case testing the constitutionality of the country’s laws on assisted suicide. The association also submitted a brief to the Supreme Court outlining its new position and some of its concerns about how changes to the law could affect medical practice.

The association’s new language gave the appearance of broad-minded neutrality: It “supports the right of all physicians, within the bounds of existing legislation, to follow their conscience when deciding whether to provide medical aid in dying.” Remarkably, the CMA’s new policy statement defines physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia without any explicit patient eligibility criteria, such as decision-making capacity or the diagnosis of a terminal illness.

A few months later, Canada’s Supreme Court issued a ruling in its Carter v. Canada decision that struck down the country’s prohibition of assisted suicide. The ruling was suspended to give time for Parliament to pass legislation that accorded with the court’s ruling, and in June 2016 the government enacted a new law on “medical assistance in dying” — meaning both assisted suicide and euthanasia. By its intervention in the case, the national medical association in Canada not only went along for the ride, but paved the way for this momentous shift.

Like the American Medical Association, the World Medical Association faces increasingly intense pressure to abandon its opposition to physician-assisted suicide. But for now it continues to adhere to its longstanding position:

Physician-assisted suicide, like euthanasia, is unethical and must be condemned by the medical profession. Where the assistance of the physician is intentionally and deliberately directed at enabling an individual to end his or her own life, the physician acts unethically.

At the association’s semi-annual meeting in October 2018, the Canadian Medical Association, along with the Royal Dutch Medical Association, attempted to convince the WMA delegation to drop its opposition. After these efforts failed, Canada left the global association.

As others have observed, Canada claimed to have made its unprecedented exit because the incoming WMA president had plagiarized a few passages from a former CMA president’s speech. (The new WMA president apologized for this breach to the satisfaction of the rest of the membership, noting that English was his fourth language and that the address had been prepared by a speechwriter.) Despite the insistence of the Canadian Medical Association, it’s hard to resist the obvious conclusion that plagiarism was a pretext, and the underlying reason for the break was the associations’ irreconcilable positions on end-of-life issues.

Following Canada’s example, the Royal Dutch Medical Association likewise resigned from the WMA this January, also citing the plagiarism incident as a flimsy pretext. It is widely known that the Netherlands has one of the most permissive assisted-suicide and euthanasia regimes in the world, even permitting euthanasia for psychiatric patients without a terminal illness.

Recent developments in Britain’s national medical association make the machinations of WMA delegates appear mild by comparison. After failing to persuade Parliament to legalize physician-assisted suicide in 2015, advocates have been busily maneuvering through the upper echelons of organized British medicine. This February, the Royal College of Physicians polled its thirty-five thousand members on changing its longstanding opposition to physician-assisted suicide. A plurality of its members, 43 percent, believed the RCP should oppose a change to British law — that is, should maintain its opposition to legalizing assisted suicide. Another 32 percent were in favor, while 25 percent wanted the association to be neutral.

But the president of the RCP, Andrew Goddard, had planned to change the college’s position to “neutral” unless a supermajority of 60 percent opposed a change in the law. So even though the smallest share of members supported this approach, and a plurality opposed it, the RCP has now taken a neutral position on the law.

Not surprisingly, several RCP members cried foul. Prior to the vote, former RCP chair of ethics John Saunders warned in a letter to the Guardian that it would be “a sham poll with a rigged outcome.” Another group of physicians wrote a letter to the Times of London arguing that the RCP maneuver was a cynical, manipulative takeover by a vocal minority of assisted-suicide advocates: “We are worried that this move represents a deliberate attempt by the minority on the college’s governing council to drop the college’s opposition to assisted suicide even if the majority of the membership vote to maintain it.” And in April, the country’s Charity Commission, a government body that regulates nonprofit entities like the RCP, sent a letter to the RCP expressing concerns about how they “dealt with and managed such a sensitive and high-profile subject matter.”

What precisely does it mean for medical societies to adopt a “neutral” position on physician-assisted suicide? Is this merely a reasonable accommodation to make room for diverse viewpoints among members — a humble acknowledgment of uncertainty? There is good reason to doubt this.

In a 2018 paper, bioethicist Daniel Sulmasy and co-authors argued that while neutrality might be a reasonable approach for a position statement circulated internally among members of a medical society, “a position statement by a professional organization, however, is oriented externally, addressing the profession, state, and the public at large about an issue relevant to the practice of that profession.” A diversity of opinion found among medical-society members does not require a neutral position by the society itself, and associations routinely take positions about which individual members may disagree — the authors offer mammogram screening and health care reform as examples. Unanimity among members is not required in order for an association to take a position. Furthermore, medical associations also take positions against practices that are legal in some states, such as capital punishment. The American Medical Association, for instance, does not permit a physician to “participate in a legally authorized execution.”

A neutral position is not truly possible on the legal question about whether assisted suicide should be permitted. To take a position that says that doctors can perform it if they want while others may choose to abstain is to take a position in favor of permitting the practice. It is analogous to a position that says that some people can choose to steal if they want, while others who find it objectionable need not steal. Translated, this means stealing is permissible.

As we’ve seen, the logical implication of neutrality is borne out by its political consequences. The switch to “neutrality” in Canada, as well as in California and several other states, paved the way for legalizing physician-assisted suicide, which suggests that moving from opposition to neutrality in effect endorses the legalization of the practice. And again, this is evident in the strategies of proponents of legalization, who invest intense lobbying efforts to get local chapters of medical associations to go neutral.

A position of “neutrality” by a medical association is not truly neutral, moreover, because legalization of assisted suicide can rapidly usher in a regime where doctors who are unwilling to participate are pressured to conform.

In the lead-up to California’s vote on the bill to legalize assisted suicide, state senator Bill Monning was quick to reassure Californians that “participation by doctors, pharmacists, and healthcare facilities, including certain hospital systems … is totally voluntary. The essence of this bill is volitional will of a patient and voluntary participation.” But in the time since the law went into effect, as legislators turned from persuading the public to implementing the law, the pressure for physicians to participate has become evident, usually under the guise of “expanding access.”

In a January 2018 hearing, Senator Monning described assisted suicide as an “important human right.” The implication is that choosing not to participate in assisted suicide is unethical. Monning suggested that medical associations should take more steps to expand access, and that creating a list of physicians willing to participate in assisted suicide would help to facilitate access for patients. Several people in the hearing also lamented that access was more difficult to obtain for minority and other disadvantaged groups, who Monning said “should have similar access,” and there was broad support for making assisted suicide a routine part of medical school and residency training for physicians.

Further, just as access to participating physicians is a practical barrier for patients seeking assisted suicide, so are the other legal safeguards that protect them against abuse: requirements to visit a physician multiple times to get approval for suicide assistance, mental health assessments, and the patient capability of administering the life-ending drug to himself. As Monning told the press, “The challenge faced by some patients — it’s rooted in the protections of the law.” But what in legal terms is called a protection can just as easily be viewed as an obstacle. Susan Eggman, a member of the California State Assembly who chaired the January 2018 hearing, asked one physician whether the requirements for patients were “too onerous.”

All these may sound like reasonable concerns for making a legally permissible end-of-life option broadly available to all who request it. But we should recognize the language of physicians’ “voluntary participation” for what it is: a fragile idea that can easily fall apart in practice.

A study this year in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that physicians and hospitals in California are not rushing to embrace assisted suicide. Of the 270 California hospitals that responded to a survey, only 106 had policies that permitted physicians to write prescriptions for lethal medications. Of the 164 hospitals that prohibited these prescriptions, 134 also prohibited prescriptions in affiliated outpatient settings. At my own university hospital, which has a policy permitting these prescriptions in outpatient settings, only a tiny fraction of the hundreds of physicians on our medical staff have opted in as potential prescribers or consultants.

But the pressure to participate will almost certainly grow. The California Medical Association gives lip service to conscience protections for individual physicians, but its official neutrality offers little assurance of protection against informal political or institutional pressures that will be placed on physicians and hospitals that refuse to participate. For now, the majority refuses to participate — but with its “neutral” stance, the CMA has abandoned that majority.

Canada’s experience illustrates even more clearly how weak these conscience protections can become. The legal regime established by the Carter ruling now places considerable burdens on physicians who refuse to participate. In some provinces, physicians who refuse to participate in assisted suicide now face discipline and expulsion from the medical profession if they do not refer their patients to physicians who will offer them “aid in dying.” For example, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, the body that licenses and regulates medicine in the province, holds such a policy. And in January 2018, it was upheld by the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

With this ruling, the court essentially declared that physicians’ conscience protections were outweighed by the goal of providing equitable access to assisted suicide. The provincial appeals court recently upheld the ruling. If the case ever reaches Canada’s Supreme Court, something like Ontario’s referral policy may well become the law of the land.

Consider the startling swiftness of this shift. As recently as 2015, physician-assisted suicide would have been culpable homicide in Canada. By 2018, in the country’s largest province, physicians who fail to participate in the same practice, or to facilitate it through referral, could themselves face severe disciplinary action. Canadian physicians who have not fallen in line with the new legal regime are in danger of being squeezed out of the profession.

In the brief that the Canadian Medical Association submitted to the Supreme Court for its Carter decision, it explained, “If the law were to change, the CMA would support its members who elect to follow their conscience.” Now that the law has changed, the association and organized medicine in Canada more broadly have abandoned physicians who choose not to participate in assisted suicide.

So goes neutrality.

What, besides the winds of change, guides the ethical standards of medical associations? Medical societies such as the American Medical Association were originally formed to internally regulate the practice of medicine, mainly by disciplining members who engaged in unethical behavior, quackery, fraud, or charlatanism. They recognized that the profession has an interest in policing its own borders and enforcing its own standards — if for no other reason than to maintain the public’s trust.

The AMA Code of Medical Ethics, first adopted in 1847, the year of the association’s founding, has naturally undergone revisions since then. The AMA now describes its code as “a living document that has evolved as medicine and society have changed over time.” Fair enough. But the living-document metaphor raises the question of whether there are any provisions in the ethics code that might be enduring, not subject to revision as society changes. As their codes of ethics “evolve,” will medical societies continue to serve a robust role in guiding and shaping the behavior of physicians? Or will the behavior of physicians, and the prevailing moods of society as a whole, dictate the changes to the codes and the terms on which medical societies operate?

The position of medical societies on assisted suicide and euthanasia depends on the more foundational question of whether the practice of medicine has a morality internal to it — a morality grounded in the mandate to heal those who are vulnerable due to illness, a morality not subject to the vicissitudes of opinion or prevailing social mores. If there is such an intrinsic and perennial morality, it is precisely this that medical societies ought to promote and defend.

It is instructive to examine again the AMA’s position on physician participation in capital punishment and torture. The AMA does not stake out a position on capital punishment per se. Its members are free as citizens to hold any position on whether the practice itself is moral, or should be legal. However, the AMA does say that as physicians its members cannot use their medical skills and knowledge to participate in carrying out capital punishment: “As a member of a profession dedicated to preserving life when there is hope of doing so, a physician must not participate in a legally authorized execution.” The role of executioner, a role recognized and perhaps required by some societies, must be clearly distinguished from the role of physician. The analogy to assisted suicide is apt: Capital punishment is a form of killing that is legally sanctioned in many states, yet by the AMA’s own reasoning, physicians must refrain from assisting. Participating in capital punishment inevitably corrupts the healing role of the doctor.

For the same reason, the AMA takes an even stronger position on physician participation in torture: “Physicians must oppose and must not participate in torture for any reason.” Moreover, “physicians must not be present when torture is used or threatened.” These positions are grounded in an understanding of medicine as a teleological enterprise — as a practice intrinsically aimed at promoting health and healing. Medicine is not merely a set of techniques or a body of knowledge — physiological, pharmacological, procedural — that can be deployed for any purpose whatsoever.

If medical associations cease to recognize an enduring morality internal to the profession — aimed only and always at healing the sick — they lose their way. For whenever physicians use their knowledge and skills for ends other than the promotion of health and healing, medicine is corrupted — indeed, is no longer medicine.

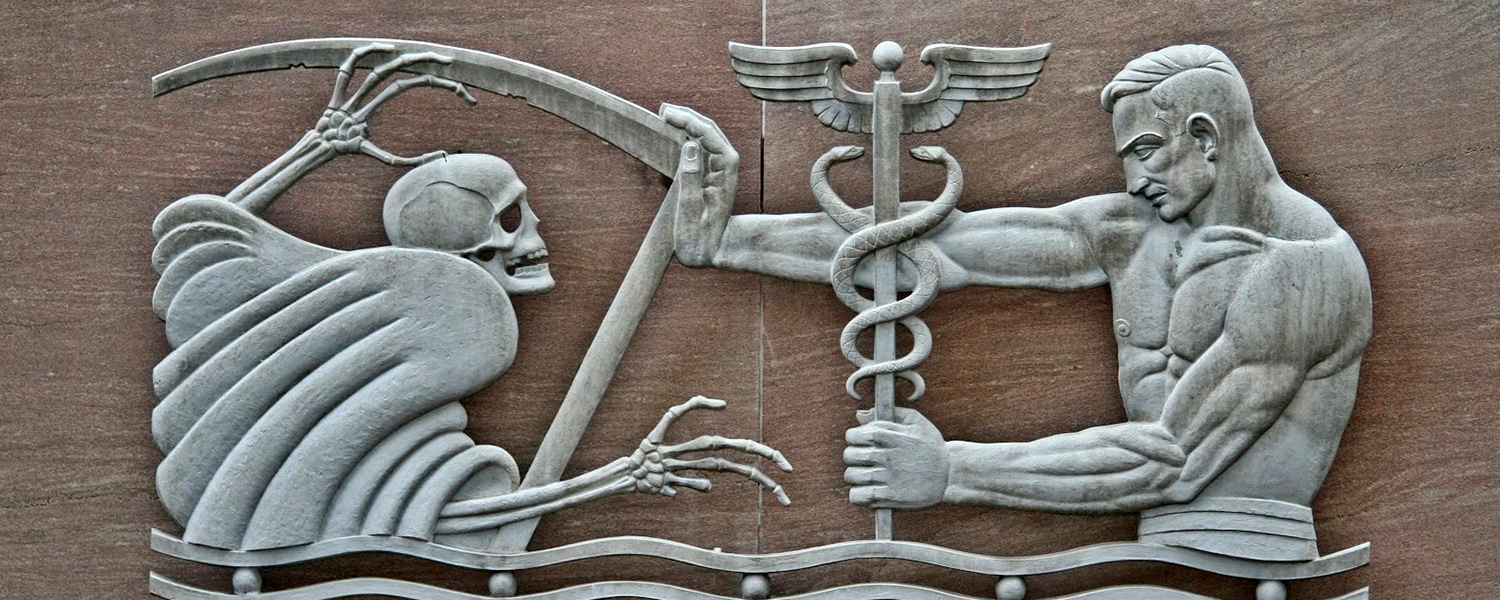

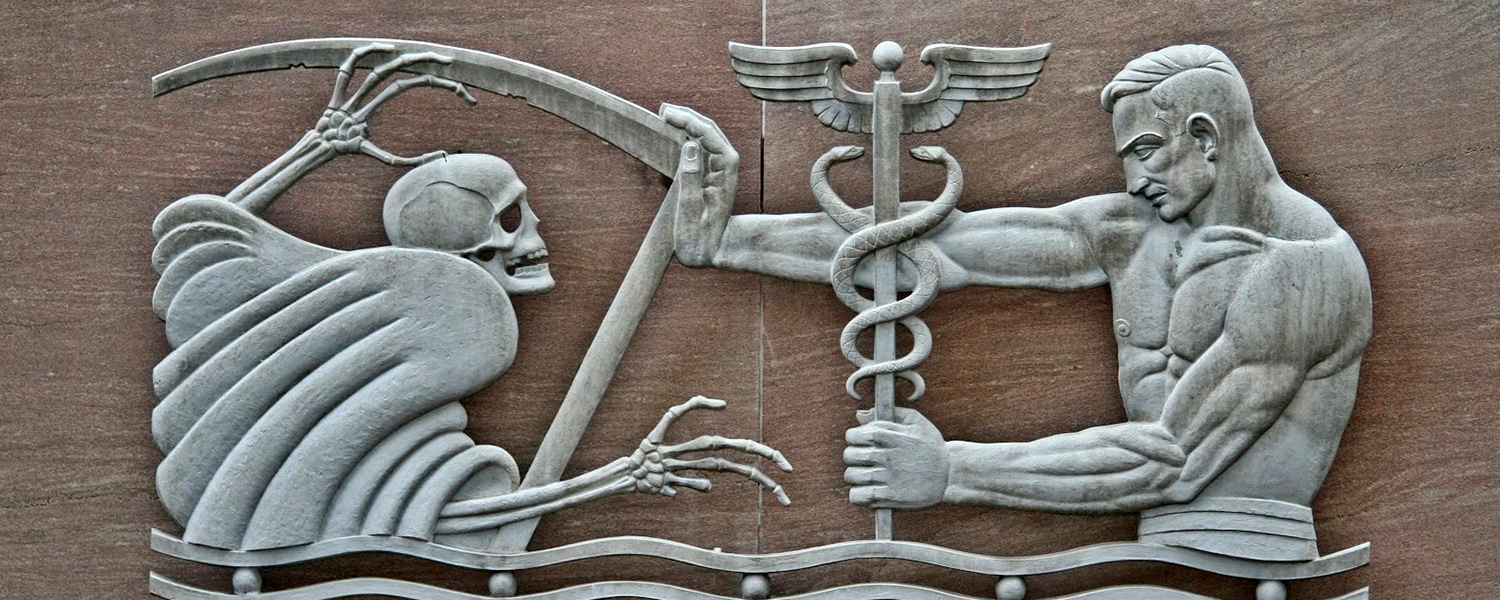

The American Medical Association’s positions on capital punishment and torture are grounded in principles that stretch back to the very origins of Western medicine. Maurice Levine, in Psychiatry and Ethics (1972), wrote that anthropologist Margaret Mead’s “major insight was that the Hippocratic Oath marked one of the turning points in the history of man.” As Levine recounts Mead’s words:

For the first time in our tradition there was a complete separation between killing and curing. Throughout the primitive world the doctor and the sorcerer tended to be the same person. He with power to kill had power to cure, including specially the undoing of his own killing activities. He who had power to cure would necessarily also be able to kill.

With the Greeks the distinction was made clear. One profession, the followers of Asclepius [the god of medicine], were to be dedicated completely to life under all circumstance, regardless of rank, age, or intellect — the life of a slave, the life of the Emperor, the life of a foreign man, the life of a defective child…. This is a priceless possession which we cannot afford to tarnish, but society always is attempting to make the physician into a killer — to kill the defective child at birth, to leave the sleeping pills beside the bed of the cancer patient…. It is the duty of society to protect the physician from such requests.

All the more so is it the duty of medical societies to protect the physician from such requests. When they abandon attempts to shape and guide the behavior of their members according to perennial professional standards, medical associations risk becoming nothing more than public relations firms engaged in the business of lobbying on behalf of members’ interests. Or worse, they become outward-facing agencies that simply notify the public of what members at any given time happen to believe on this or that issue. It’s unclear whether medical associations today have already become just that. As more and more of them abandon their traditional opposition to physician-assisted death, they have also drifted in this direction.

Consider the language adopted by the Canadian Medical Association for its purpose statement, which could as easily have been written by a PR firm as by medical professionals: “Our purpose is to drive meaningful change.” The nature and direction of this change is nowhere specified. The association acts as “changemaker,” “champion,” “collaborators,” “amplifier,” and “steward.” Its mission is “empowering and caring for patients,” and its vision is “a vibrant profession and a healthy population.” This language is vacuous and incapable of providing any ethical guidance to the profession of medicine. Many occupations work to promote a “healthy population”: personal trainers, dieticians, public health officials, dentists, podiatrists, massage therapists, environmentalists, and sociologists of various stripes. The association makes no mention that physicians promote a healthy population specifically through the work of healing the sick. It is little wonder that the association has been blown about so readily by the winds of social change in Canada.

Medical associations that have adopted a position of neutrality on assisted suicide have abdicated their role in guiding and shaping the profession and the behavior of members. These societies now follow, rather than attempt to lead, the profession. They chase fashionable novelties rather than adhere to enduring principles. Our society now faces an astonishing range of new ethical issues related to the practice of medicine, including the use of powerful gene-editing techniques that could potentially be deployed beyond the traditional boundaries of healing in an effort to reshape human nature. This is not the time for medical societies to relinquish their original principles and purpose, or to abandon the idea of ethical self-regulation of the profession.

We can now raise a more fundamental question: Should assisted suicide and euthanasia be considered a medical issue in the first place? One might argue that whether we should assist people in taking their own lives is a societal and legal question, one that should be kept entirely out of medicine. After all, one could train a high school graduate in a weekend or two on the technicalities of administering a lethal drug. This practice requires neither a medical degree nor much skill. Canadian bioethicist Margaret Sommerville has dubbed the proposal to de-medicalize the issue “taking the white coat off euthanasia.” She writes, “When the cloak of medical approval is absent, the public are much more likely to question the wisdom of legalizing it.”

This is precisely why official medical societies’ positions carry so much weight. In their deliberations, they increasingly present assisted suicide and euthanasia as issues about which society must decide, implying that physicians should not get in the way. But these same proponents then propose legislation that would require physicians not only to be gatekeepers but facilitators of these practices. Proponents want a libertarian regime of assisted suicide, but one made more palatable by medical trappings. They cannot have it both ways.

About euphemists, G. K. Chesterton remarked, “Short words startle them, while long words soothe them. And they are utterly incapable of translating the one into the other, however obviously they mean the same thing.” When assisted-suicide advocates say that doctors should be allowed to help their patients “die with dignity,” their audience may be lulled to sleep and neglect to press them for specifics. Say instead, however, that one person should be allowed to kill another person, or help another person kill himself, and the same audience may wake with a start.

Several years ago, when assisted-suicide debates began surfacing in the United States, my father quipped, “Why not truck driver–assisted suicide?” Behind this seemingly flippant remark is a morally serious point. When we put the matter this starkly, assisted suicide and euthanasia appear to be simply what they are: the killing, or the facilitation of killing, of one human being by a fellow human being. This is an inherently repugnant reality. And this is why advocates of assisted suicide and euthanasia have always coveted the prestige of the medical profession: The white coat is necessary to cloak an ugly reality with an appearance of respectability.

Nobody should participate in helping another person take his or her life. But if the public insists that assisted suicide and euthanasia be permitted, medical associations should be clear about what it is — and should confidently condemn places like the Bay Area End of Life Options clinic. Organized medicine should remove the prestige of our profession from this practice, leaving it in the hands of a cadre of trained thanatologists. At least then physicians can remain what we have been since ancient times: healers of the sick, not takers of human life. Neutrality is not an option.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?