In a world of serial storytelling, characters commonly outlive the actors who play them. Makers of film and television find ways to respond to the death of an actor, from recasting a role without comment (like Dumbledore in the Harry Potter films) to making the changeover of lead actors a central motif of a series (the Doctor in Doctor Who). Disney pioneered a new response in its latest Star Wars movie: resurrecting a deceased actor to reprise a role from beyond the grave. The technology on display here is impressive. But it both denigrates the craft of acting and violates the dignity of the human body by treating it as a mere puppet.

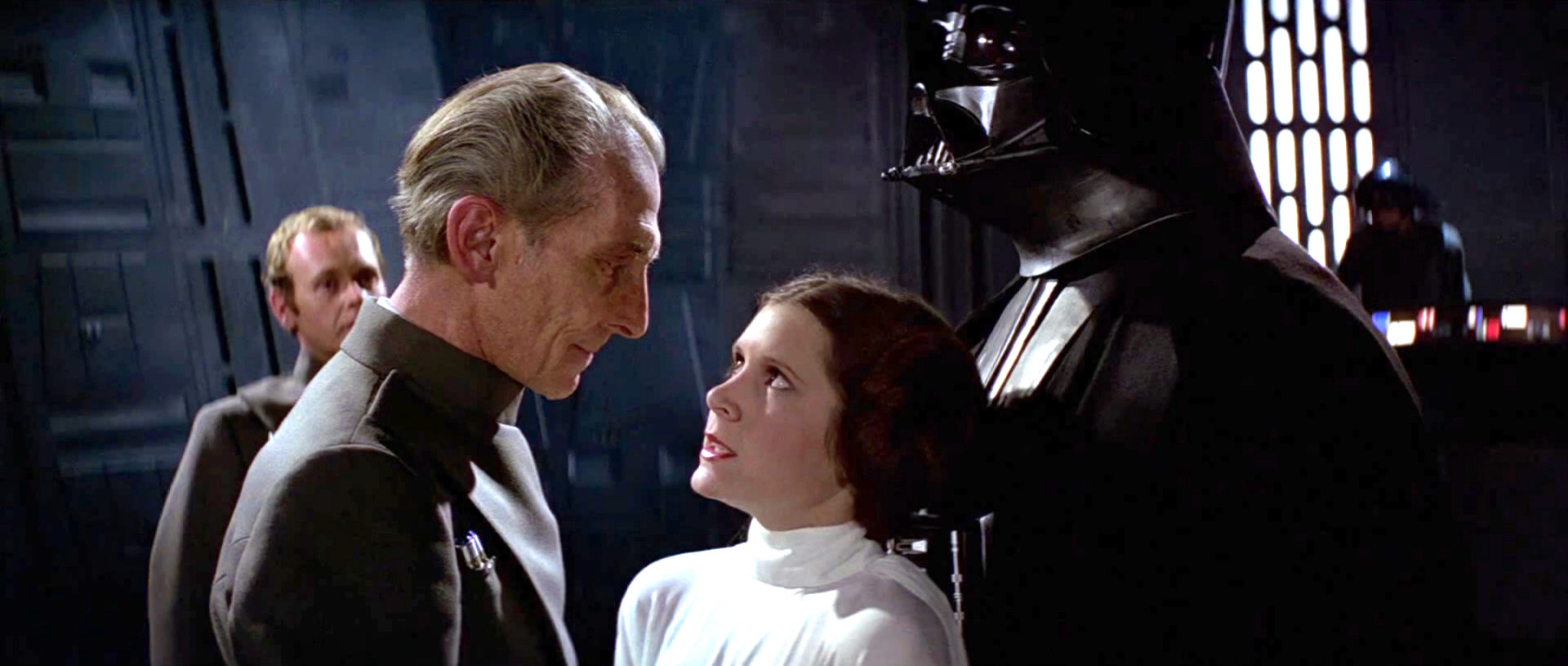

Peter Cushing’s performance in 2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story is remarkable because Cushing died in 1994. Industrial Light & Magic’s computer-generated imagery (CGI) wizards digitally resurrected Cushing to once again portray the villainous Imperial Grand Moff Tarkin, a central antagonist of the original 1977 Star Wars, in which the character brutally orders the destruction of Princess Leia’s home planet of Alderaan. Recreating Cushing for Rogue One was experimental in two senses: Disney was testing out both the technology and audiences’ reactions to it.

A sad accident of timing made another use of CGI in Rogue One more attention-grabbing. The movie concludes with a brief cameo of a young Princess Leia, also created with CGI. In this case, the original actress, Carrie Fisher, was alive to see the result and give it her approval. But Fisher died on December 27, 2016, during the theatrical run of Rogue One. For many viewers, this made the brief appearance of a young Princess Leia in the film all the more uncanny. Even reviews written before Fisher passed away singled out the de-aged Leia as a more distracting character reprise than Tarkin, especially since it was meant to close out the movie on a note of hopeful nostalgia. As reviewer Kelly Lawler put it, “While Tarkin is merely unnerving, the Leia cameo is so jarring as to take the audience completely out of the film at its most emotional moment.”

And yet, Cushing’s posthumous “performance” represents the more groundbreaking and dubious use of the technology. CGI de-aging of still-living actors is already widespread in the industry, in ways both subtle (the “Photoshopping” of movie stars to unrealistic physical perfection) and obvious (creating younger versions of actors like Michael Douglas and Kurt Russell for flashbacks in recent Marvel movies). Digital resurrection, on the other hand, is a much more uncharted territory.

Grand Moff Tarkin appears throughout Rogue One, to outward appearances as if the Peter Cushing of 1977 had agreed to step through time for this 2016 film. But Cushing himself could not, like Fisher, approve of the studio’s use of his likeness. Instead, his estate gave Disney the go-ahead. How confident can we be that the studio and Cushing’s heirs — actually, his former secretary Joyce Broughton, the overseer of his estate — correctly discerned the wishes of an actor who died more than twenty years ago, about his apparent resurrection using a technology that didn’t exist during his lifetime? And, leaving aside the question of consent, what would the ethical and artistic fallout be should the use of this technology become widespread?

Digital resurrection raises broader questions than simply whether this or that CGI revenant was respectful to the dead and artistically effective. A few recent instances are hard to fault. For example, films featuring actors who died during production have recreated the dead actors’ likenesses to finish the film. Screenwriter Chris Morgan rewrote the fate of Paul Walker’s character in Furious 7 after the actor’s death, with Walker’s brothers standing in for him to film additional material that served as a farewell and tribute to Walker. Weta Digital handled modeling Walker’s face and superimposing it on his brothers. Fans of the Fast and the Furious franchise found the send-off for Walker touching. But obviously, in this case, the filmmakers used the technology out of what they felt was necessity.

In Rogue One, however, Disney made Cushing a test case for a digital resurrection freely chosen by the filmmakers. There was no overwhelming narrative need to include Grand Moff Tarkin in this Star Wars story. The script has its own cast of bickering Imperial antagonists who could have lost command of the Death Star by the film’s end without the Grand Moff appearing in person to requisition it. The reason Tarkin is in the movie is to serve as an experiment in filmmaking technology. Let us see, then, what the Cushing experiment reveals about the merits of digitally resurrecting the dead.

Before turning to the technology, let us begin with the man. Peter Cushing was born in Surrey, near London, in 1913. He was set on becoming an actor from an early age. As a child he earned pocket money by performing puppet shows for family members. When he came of age, in defiance of his father’s advice and wishes he followed in the footsteps of his stage-actor grandfather and sought to make a life as an actor, first on stage, then on screen.

Cushing’s career was filled with setbacks. Initially, he had little success in Hollywood. His first role was in the 1939 The Man in the Iron Mask. Rather ironically, given his most recent role, Cushing served in his first film as a stand-in for the lead actor, Louis Hayward, who was playing dual roles as Louis XIV and his twin. Though Cushing also had a separate bit part in the film, he did not appear in the finished footage as a stand-in — it was edited using only Hayward’s depiction of the two characters. Cushing was just there so Hayward could have a real person to act with during the filming.

Cushing returned to England during World War II, dispirited and fighting what he described as an extended nervous breakdown. He was ineligible for military service due to the lingering effects of old rugby injuries, but he entertained the troops by touring with a company of the Entertainments National Service Association, the British equivalent of the USO. There Cushing met and married Helen Beck, also an actor.

As he approached middle age, still struggling to find film work, he worried that he was a failure in life. He earned praise for playing the small but memorable role of Osric in Laurence Olivier’s 1948 Hamlet, but further film parts eluded him. At his wife’s encouragement, he sought work in television, where he finally found some success and played roles like Mr. Darcy in a 1952 miniseries of Pride and Prejudice and Winston Smith in a 1954 live play of Nineteen Eighty-Four, both to great acclaim.

Following his star turns on television, in 1957 Cushing joined the fledgling Hammer Horror film line to play Baron Victor Frankenstein in The Curse of Frankenstein. He wound up a screen horror icon. For twenty years he was a mainstay of horror films, frequently playing the Baron in Hammer Horror’s Frankenstein films and Professor Van Helsing in their Dracula films.

Cushing had a particularly interesting relationship with undeath between these two famous recurring roles. As Frankenstein, he imbued corpses with a mockery of life; as Van Helsing, he put down the undead with a stake through the heart. Cushing himself pointed out this cyclical pattern in a 1964 interview: “People look at me as if I were some sort of monster, but I can’t think why. In my macabre pictures, I have either been a monster-maker or a monster-destroyer. But never a monster. Actually, I’m a gentle fellow.”

Gentle he might have been, but thanks to Hammer and many other horror studios, Cushing’s filmography was full of technicolor gore and Gothic excess. He had the gaunt face and tall frame for it, though perhaps sometimes more of a twinkle in his eye than you’d expect from a master of horror. He starred in films with unforgettable titles like Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, The Flesh and the Fiends, Twins of Evil, The Hellfire Club, The Man Who Finally Died, Island of the Burning Damned, Torture Garden, Horror Express, The Blood Beast Terror, And Now the Screaming Starts!, and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors — Cushing, of course, played the titular Dr. Terror.

Cushing’s less horrific roles included Sherlock Holmes in another film series and the lead in two adaptations of Dr. Who for the big screen. His fellow actors attest to his old-fashioned manners and his professionalism — he once consulted with a surgeon to make sure he was handling a scalpel realistically. He became fast friends with his frequent co-star Christopher Lee, who was Dracula to his Van Helsing and the Creature to his Victor Frankenstein. (Following in Cushing’s footsteps, Lee went on to play a Star Wars antagonist in the prequel trilogy.)

By all accounts Cushing was completely devoted to his wife Helen, and devastated when she died of emphysema in 1971. Later in life, Cushing spoke of having had suicidal thoughts after her passing. But he emphasized the words his wife had written to him on her deathbed. As he recalled them in a 1990 TV interview, “‘Do not be hasty to leave this world because you will not go until you have lived the life you have been given. And remember: We will meet again when the time is right. That is my promise.’”

In an interview with the Washington Post fifteen years after Helen’s death, Cushing seemed still to be mourning her. But he also spoke reverently and meditatively of God and His timing. Observing the arrival of winter, Cushing said, it’s “when nature apparently dies. It’s God’s way of saying, ‘That’s also for you, chum. Just do your best here, because you’ve got to do a lot better where I’m taking you.’”

Though not conventionally religious, Cushing seemed to turn to scripture for comfort. In the 1990 interview, he quotes John 14:2 (“In my Father’s house are many mansions”) and Hebrews 12:1 (“let us run … the race that is set before us”) in reference to his wife’s death and his living on. Cushing arranged for a strain of rose to be named after his wife: the Helen Cushing Rose.

Cushing’s part in 1977’s Star Wars came about because George Lucas felt the film needed a villain with a face to share the antagonist role with the masked Darth Vader. Cushing (according to a widely circulated quote of uncertain origin) took the part because “I try to consider what the audience would like to see me do and I thought kids would adore Star Wars.” He was right, of course, and Grand Moff Tarkin became one of the most famous roles of his long career.

With Cushing having died of prostate cancer in 1994, when Lucasfilm wanted to bring Tarkin back for a cameo in 2005’s Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith, they considered creating a digital mockup of a younger Cushing. Instead, as animation director Rob Coleman recounted on the movie’s DVD commentary track, they cast another actor, Wayne Pygram, and used facial prosthetics to make him look more like Cushing.

For 2016’s Rogue One, the filmmakers took a different approach. Initially, director Gareth Edwards considered simply recasting the role. But the visual effects supervisor, John Knoll (also an executive producer of the film and the originator of its story concept) convinced Edwards they could bring back Cushing.

The technique was executed by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), the special effects studio founded by George Lucas, where Knoll is a Chief Creative Officer. ILM used cutting-edge technology to make a digital model of Peter Cushing and superimpose it on stand-in actor Guy Henry, who wore a head-mounted camera rig to capture every detail of his facial motion. Then the digital wizards transferred those motions to their virtual Tarkin maquette, making frame-by-frame adjustments to bring Henry’s movements in line with those of Cushing archive footage. Fortunately for them, they also had a three-dimensional cast of Cushing’s face to use for reference — a lifecast made for the 1984 movie Top Secret. The work took place over eighteen months. Tarkin appears frequently in Rogue One and interacts with the main villain, Director Krennic (played in the flesh by Ben Mendelsohn), taking over command of the newly built Death Star.

The resulting digital resurrection seems universally described with the word “uncanny” — either as praise for its uncannily lifelike quality or as a criticism of its falling in the “uncanny valley.” The uncanny valley is the phenomenon in which things that appear very nearly but not entirely human seem strange and creepy. It’s an ongoing obstacle in fields like robotics and computer animation, or anywhere that people try to build lifelike human simulacra. Some point to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the first description of the uncanny valley, as Frankenstein expresses his revulsion toward the creature he created:

How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavoured to form? His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful…. but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion, and straight black lips…. A mummy again endued with animation could not be so hideous as that wretch.

Perhaps the modern Promethei of the CGI world will follow the example of Cushing’s indefatigable Dr. Frankenstein and keep creating creatures in the hope of bridging the uncanny valley. But a world in which dead actors mingle seamlessly onscreen with living ones, though it may sound exciting, denigrates the craft of acting. Acting is the art of presence. A digital resurrection, however well-intentioned or well-executed, has at its heart an absence.

Now, there are ways that Cushing’s digital resurrection is not so different from techniques used in other Star Wars films. Guy Henry wore the mask of Grand Moff Tarkin; puppets and masks were used to give life to characters in the first three films. Is the 2016 version of Tarkin so different than, say, the Darth Vader of the original trilogy?

Darth Vader was embodied by bodybuilder and character actor David Prowse (who, as it happens, once played the Creature in a Cushing Frankenstein film). Disliking Prowse’s West Country accent, George Lucas had James Earl Jones dub over Vader’s lines. When Vader’s face was finally shown in Return of the Jedi, he was played by Shakespearean actor Sebastian Shaw. Yet much of the character’s menace comes simply from his black costume, intimidating mask, and the distinctive sound design of his breathing apparatus. It’s a collaborative performance, but a compelling one.

The difference, of course, is that Vader’s mask is not the face of a dead man. Though we suspend our disbelief while we watch the film, we find it completely plausible that Vader’s body, voice, and face were all provided by different actors, just as we understand that puppet characters like Yoda and Jabba the Hutt have unseen operators. Vader’s mask is part of his character. His character is a visual icon of menace first, a human being second (and only sort of).

In considering the CGI Tarkin, there is no small irony in recognizing that the character was created for the original Star Wars specifically to give the Empire a human face, to offset the artifice of Vader’s masked visage. Peter Cushing brought his face, and with it his gentlemanly demeanor and his chops as a veteran of genre film. Cushing cannot simply be turned into a mask to recreate his performance.

Star Wars, as a phenomenon, relies on an alchemical mixture of technical and narrative creativity and the charisma of its actors: Darth Vader’s mask staring down Alec Guinness’s weathered face; clever miniatures to make the Millennium Falcon fly, the chemistry between Carrie Fisher and Harrison Ford to make us care; Frank Oz puppeting the wise Yoda while Mark Hamill gamely plays the impetuous pupil.

The new Star Wars films work when they remember this formula, as in The Force Awakens when John Boyega’s Finn bonds with the droid BB-8 by exchanging thumbs up. Viewers are ushered into the space fantasy thanks to engaging and identifiable performances by actors. It’s the chemistry of impressively realized droids and aliens meeting with real, likeable human scene partners that gives the Star Wars universe its enduring magic. What becomes of that alchemy when the human side of the equation is replaced with a high-tech puppet?

An acting teacher of mine passed on what she claimed was an old saying, advising actors to be “the real frog in the artificial garden.” This means that the sets and costumes and given circumstances of a fictive world, be they ever so fanciful or abstract, are simply reality for one’s character. One should react as a real person would to these surroundings, telling the truth under imagined circumstances. This is not just a bargain the actor makes with the audience in exchange for the audience’s suspension of disbelief. The actor’s realness helps the audience to suspend disbelief, modeling what it is like to live in the reality of the story.

How will it affect audiences to know that the actor himself, the human face and body we identify with, is a piece of cinematic illusion? Reality, usually that of the actor, is our bridge into the fiction, fantasy, or surreality of the work. There is nothing any longer to hook us in when all we can see in the artificial garden is the artificial frog.

Acting, again, is the art of presence. The first taboo that Rogue One’s use of at-will resurrection violated was an artistic one. We don’t want actors who are the puppets of directors, each facial tic reflecting a director’s decree rather than a performer inhabiting his character’s reality. But that’s precisely what we get when we Frankenstein together an uncannily lifelike facsimile of an actor and give technicians the puppet strings.

Masks can be effective acting tools. From the ancient Athenian theater on, performers have donned false faces to perform larger-than-life roles. But actors have developed an arcane set of rules and traditions surrounding mask work. Neutral masks, the blank, expressionless masks developed as a training tool by Jacques Lecoq, represent a blank-slate character, a past-less, knowledge-less entity that actors take on in order to explore the world as a complete naïf, discovering everything from the ground up. Another class of masks are those of commedia dell’arte characters, like the Harlequin and the Pantaloon, cartoonishly exaggerated grotesques that represent broad and comic archetypes.

A mask designed to be a convincing replica of another person’s actual face, however, is not part of this tradition. Certain shamanic rites may involve this, but not normal mask work in the theater. There’s a ghoulishness in turning a real, particular person into a mask, especially after that person is dead.

Guy Henry, the actor whose face was replaced by the digital Cushing mask, has expressed something akin to this unease. Henry, the vocal mimic and body double who channeled Peter Cushing in Rogue One, wore two types of masks. On screen, we see his body, voice, and facial movements animate Cushing’s digitally applied face. On the set of the film, he was wearing a more physically unwieldy mask, in the form of the camera apparatus that tracked his smallest facial movements to help the CGI wizards in post-production. In a Hollywood Reporter interview this year, Henry says of the setup:

There’s something very claustrophobic, there’s something very distancing about having the head cam gear. It’s very unwieldy…. It’s very hard to find a performance with that thing sticking on your head, the lights and lenses shining on your eyes. It’s a very particular way of working. I must say I found it terribly frightening.

This head gear is similar to what other actors playing CGI characters have used — most famously, Andy Serkis as Gollum in the Lord of the Rings films. What’s unusual is using the rig for a human character, particularly using it to recreate a dead man’s face.

Body doubles and stunt doubles are part of the filmmaking ecosystem, and have been for a long time. Peter Cushing, as noted, was himself a body double in the 1939 The Man in the Iron Mask, so that Louis Hayward could play both the French king and his twin brother. But even though Cushing’s half of each scene didn’t make it into the film, his presence gave Hayward an actual partner to act with.

Henry had a different task, and one he seems to have found nerve-racking: mimicking the deceased Cushing as closely as humanly possible. As he explains, “It was genuinely frightening, because I didn’t want to let down a huge movie, and equally, I didn’t want to let down Peter Cushing.” Of course, any actor inheriting a part from a beloved predecessor might experience this trepidation. Many of today’s flood of reboot films pose the question of how an actor can honor an iconic previous performance while making the character his or her own — Chris Pine playing James Kirk in the shadow of William Shatner, or Ewan McGregor playing Obi-Wan Kenobi in the shadow of Alec Guinness.

Henry, by contrast, doesn’t think of the role of Grand Moff Tarkin as his, or even think of his performance as a portrayal of Tarkin. Rather, he says, “Normally as an actor, you are you pretending to be another person. Here, I was me pretending to be Peter Cushing pretending to be Tarkin.”

This didn’t leave room for Henry to perform in any traditional sense. A performance of a performance is not a double remove, but something else entirely. CGI masks collapse the original actor into the role, making their successors not actors but imitators. Unlike an overt comedic impersonation — say, Kate McKinnon’s Hillary Clinton on Saturday Night Live — this sort of covert imitation is eerie. It makes every attempt to hide its nature; yet we cannot help but recognize it as a false image of a departed face.

Guy Henry tries his best to defend Rogue One’s resurrection of Cushing: “Not to have Tarkin in it would be just a shame, and I think they have done it very honorably.” But he does not sound sanguine about future uses of this technology, saying, “I think and hope it won’t be a commonplace thing.”

Why does he think and hope so? Is it for the sake of actors like him, asked to put on cumbersome headpieces and burdensome personae? Or is it for the sake of the dead actors being impersonated? Henry says, “When people were talking about the ethics of bringing someone back who was long dead, I could see that if it was done for the wrong reason or something a bit seedy or just for the sake of it, that would have been wrong.”

This brings us to the second taboo Rogue One violated: the taboo against dishonoring dead bodies. Note that I say “dead bodies” and not “the dead.” The CGI Cushing-as-Tarkin is not disrespecting Cushing’s memory in the way that, say, slandering him at his funeral might. No, what is violated here is closer to a religious than a social taboo.

This taboo, of course, is at the heart of the stories of both Dracula and Frankenstein. These gothic tales revolve around the hubris of restoring life to corpses through science or magic, and the unholy and unhappy fates of such monsters. One might think that Cushing’s Hammer Horror résumé makes him the most appropriate test subject for the new technology — but the tribute seems decidedly twisted if we remember the point of the Frankenstein story. Would Cushing appreciate being pseudo-reanimated as another man’s macabre mask?

Some might object that it is an exaggeration to call a CGI resurrection a form of corpse desecration. After all, no hunchbacks were sent to disinter Cushing’s remains in the dead of night. It’s just pixels arranged on a computer for a movie’s special effects. It’s not real!

This reply betrays an untenable division between the body’s matter and its form. If we concede that the human body has some sort of dignity, such that it is not appropriate, even in death, to treat it like any other piece of meat, then that dignity does not reside only in the matter or only in the form. The matter of the human body has composed other bodies (animal, vegetable, and mineral) and will go on to compose still more. Its humanness arises because the matter exists in human form, as the individuality of each person arises from his or her particular form.

Peter Cushing’s spare frame, sharp cheekbones, and long limbs are part of what made him him; they are essential to his Cushing-ness. Creating a convincing facsimile of his living, breathing, moving form after his death should not be undertaken lightly, any more than exhuming his corpse should be. The grave-robbing version is surely more egregious. Yet if it would be wrong to make a puppet of a dead man’s mortal remains, then it is also wrong to make a puppet of a dead man’s imitated form. A simulacrum is fraught with the dignity of the individual it represents.

Dishonoring the remains of the dead is a near-universal, but poorly articulated, taboo. Many people agree that it is wrong without having a metaphysical framework that justifies their belief in the dignity of the human body. But the widespread unease at the CGI Cushing testifies to the power and wisdom of this taboo, however inchoate.

The technology of digitally bringing deceased actors back to the screen runs counter to this humane impulse, this feeling that it is proper to allow the dead to remain buried. Perhaps it is not only technological advances but also the normalization of destructive means of disposing of dead bodies (like cremation) that allowed Industrial Light & Magic to contemplate Frankensteining Peter Cushing. The central violation of at-will digital resurrection is that it wrongs the dead subject by making him into a puppet.

There are less philosophical and more practical reasons to shun the normalization of CGI technology. It accelerates the degradation of the film industry into a soulless factory. And it gives a dangerous tool to purveyors of misinformation and harmful fantasy.

Technology much like that used in Rogue One is opening a new front in the “fake news” wars. A July 2017 episode of Radiolab dives down the “technological rabbit hole” of new video and audio editing software, such as Adobe Voco and Stanford’s Face2Face project, that allows users to put whatever words they want into the mouths of whoever they want, including celebrities and politicians.

The Radiolab hosts were astonished by how dangerous the technology was, and how blasé its engineers about the potential for abuse, even in the face of warnings from the media world. Jonathan Klein, a former president of CNN, asked, “How do you have a democracy in a country where people can’t trust anything that they see or read anymore?”

The response from Ira Kemelmacher-Shlizerman of GRAIL, the University of Washington’s Graphics and Imaging Laboratory, was a resounding meh. She is a technologist, she explained. Her role is to blaze a new trail, ours to reckon with the consequences: “Scientists are doing their job in inventing the technology and showing it off and then we all need to think about the next steps, obviously. I mean, people should work on that.”

This answer does not inspire confidence. This technology could potentially turn every public figure who’s been in enough available footage into a puppet like Rogue One’s Grand Moff Tarkin. What will happen when anyone can create a convincing video of the president or any other global leader saying anything and share it online? Is it responsible to perfect and popularize this technology?

Fake news purveyors are not the only ones being done a favor by this new development. It’s not hard to imagine pornographers embracing the endless possibilities of CGI recreation. After all, practically every new technology in the world of communication and entertainment is eventually put to pornographic use, and the desires of porn users surely extend to deceased actors and celebrities. It’s the next logical step after crassly commercial uses of the technology, like bringing back Audrey Hepburn to sell chocolate bars in commercials.

Now, the voraciousness of the porn and advertising industries should not frighten us so much that we never develop any new technology. But it should give us caution as we approach ethical edge cases. Not every end-user of a dubious technology like digital resurrection will operate with the respect and propriety of brand-conscious Disney imagineers.

Even if we bracket the real-world consequences, digital resurrection will have a baleful effect on Hollywood. It makes possible post-human performances that accelerate the transformation of film from art to product. There are already many forces within the film industry pushing its movies to be more and more slick, generic, and commercial, from extensive pre-visualization — a process that essentially gives visual effects studios a first pass on a film, often locking in expensive effects sequences before the script is even finalized — to reliance on CGI spectacle itself.

If this technology removes the need for an actor’s real presence entirely, we may see even more soulless digital maskery in cinemas everywhere. It’s a sad truth that talented actors are often willing, for the right price, to lend their voices to animated waste — literally, in the case of Sir Patrick Stewart’s role as “Poop” in this year’s execrable Emoji Movie. An artistic danger of CGI recreation is the possibility of ostensibly live-action films that are similarly hollow, with actors authorizing use of their likenesses and filmmakers generating whole new “performances” out of existing footage. We’d lose the pith and presence of acting itself and cross a new threshold in the degradation of collaborative storytelling. Instead of actors who make choices about their roles in collaboration with a director, we’d have convincing actor-shaped puppets operated by behind-the-scenes forces.

The danger of giving a studio untrammeled control of actors’ bodies, or simulacra thereof, is not an abstract question. Peter Cushing’s career provides examples. Near the end of the filming of Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, a Hammer Horror executive decided the movie needed to be sexed up for American audiences and insisted on adding a scene of Cushing’s Dr. Frankenstein raping the film’s heroine, Anna (played by Veronica Carlson). Cushing objected to the scene as gratuitous. Ever the gentleman, he apologized to Carlson on set and prevailed on the director to cut short the filming of the rape scene, making it shorter and less explicit. In the end, the scene was not used in the U.S. release of the film.

In a more amusing example of Cushing’s conscientiousness during his Hammer career, we have this story of him working on the 1959 The Mummy. Cushing was, of course, playing the heroic archaeologist opposite Christopher Lee’s reanimated mummy. Cushing was distressed by a fanciful promotional poster for the film that depicted a beam of light passing through a gaping hole in the mummy’s chest. Wouldn’t the audience feel cheated if that image never occurred in the movie? Cushing convinced the director to let him drive a harpoon through the mummy’s chest during a fight scene, thus justifying the poster image. Here was another moment that would only happen with a live actor. Perfectly compliant digital recreations of actors would respond to the studio’s whims rather than acting as a check on them or offering their own flashes of inspiration.

There are some reasons for hope. Possibly in response to the uneasy reception of CGI Tarkin, Disney has denied that Carrie Fisher will be digitally resurrected for the planned Star Wars: Episode IX. Instead, reports suggest that producers have significantly reduced Leia’s role in the story, and will rely on existing footage when she does appear.

But these signs are quite faint. A rush to protect the dignity of one beloved actress in the immediate aftermath of her death does little to suggest a general turn against digital resurrection. Just a few months after Rogue One’s release, Adam Nimoy, son of the late Leonard, expressed openness to his father being brought back via CGI for future Star Trek films. And a 2015 report in Vice magazine quotes a founder of a visual effects studio, who offers this sobering glimpse into the future of the industry:

“An actor that is alive today can use a scanner to get a digital 3D model of their appearance, and then sell a studio the right to use their image for, say, five movies after their death,” he told me when we met at Framestore’s studios in central London. “Actors who are very young and think they’re going to have a successful career can start scanning their bodies periodically, so they can act in different age ranges, either when they are alive or dead.”

Digital resurrection, finally, has the potential to give us an illusory power over death itself. Nigel Sumner, an ILM Visual Effects Supervisor, shared a story of his own mother seeing Rogue One, unaware her son had worked on resurrecting Peter Cushing for it. She said Cushing “‘looked amazingly well for someone of his age.’” Being able to erase the limitations of mortality gives god-like abilities to the masters of this technology. Naturally, they look to applications beyond entertainment, such as therapeutic post-mortem encounters. In the Radiolab episode, Steven Seitz of GRAIL and Google expressed the hope that this technology could someday virtually bring someone back from the dead, letting us talk face to face with (his chosen examples) Albert Einstein or Carl Sagan.

Many people, in the midst of grief, wish for the closure of one last conversation with their departed loved one. We may soon be able to give them that. But who should script what the virtual revenant says? However benevolent our intentions, such a use of this technology would amount to toying with the bereaved. We cannot truly bring back the dead, only empty illusions of them, and we do a disservice to living and dead if we make this illusion more impeccable.

If Tarkin must appear again, take the route of Revenge of the Sith and recast the role. Let’s not drag Peter Cushing back into the land of the living. He has fought the good fight and finished the race. Leave him with his beloved Helen. Don’t turn the monster-maker and monster-destroyer into a digital monster.

One piece of trivia about Peter Cushing’s performance in the original 1977 film is treasured by many Star Wars fans. The black riding boots provided by the wardrobe department for Imperial officers pinched Cushing’s feet painfully — he had exceptionally large feet. He got permission from George Lucas to remove the uncomfortable boots and instead play the role in carpet slippers, and the camera operators adjusted by filming him only from the knees up or else with his feet obscured by set pieces. In an interview, Cushing recalls the irony of playing an iron-fisted totalitarian in such soft footwear: “So for the rest of the film I stomped around, looking extremely angry, very cross, with that dear little Carrie Fisher, as old Grand Moff Tarkin in carpet slippers.”

This story endures in part because it is simply charming, in part because it illustrates the humanity and presence of an actor’s performance, even when he plays a villain — or, as Cushing describes the part, a “very cross, unpleasant gentleman.” We root against Tarkin, as the Grand Moff is a smug, Imperial mass murderer, yet we are glad to remember that just off-screen are those carpet slippers, an objective correlative of Cushing’s warmth and gentility. Whatever the role, a good actor imbues his performance with an irreducible human element.

The ghost of Cushing we see summoned in Rogue One is missing that human element. He’s less than the sum of his parts: a dead man’s face, a living man’s voice, a whole team of programmers’ code. More machine now than man, the uncanny new Tarkin has an absence at its heart. It’s jackboots all the way down.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?