Laudato Si’ provides a moral framework for addressing climate change based on Christian obligations to help the global poor most affected by it. In stressing these obligations, the encyclical fills a large gap in discussions of climate policy, which are replete with statements of what should be done but tend to lack a convincing moral framework for explaining where such obligations comes from or why they should be accepted when they conflict with particular interests.

While the encyclical considers pollution, waste, and the loss of biodiversity as key aspects of what it calls “the present ecological crisis,” climate change is a central concern because

its worst impact will probably be felt by developing countries in coming decades. Many of the poor live in areas particularly affected by phenomena related to warming…. They have no other financial activities or resources which can enable them to adapt to climate change or to face natural disasters, and their access to social services and protection is very limited.

For instance, when plants and animals cannot adapt to a warming climate, the encyclical explains, the poor depending on them for their livelihood are forced to migrate, with consequences not unlike those that refugees face. This image is based on one of the few propositions about climate effects that is widely accepted in the scientific community — that harm is likely to be concentrated in poor countries in equatorial regions — even if there is little agreement on what should be done about it.

Unfortunately, the encyclical’s presentation of the roots of the ecological crisis mostly blames industrial countries for all the world’s ills, implying that restorative justice is the reason for action. In particular, the encyclical insists that wealthy nations must reduce not only their greenhouse gas emissions but also their standard of living in order to aid the global poor. It emphasizes the harm that the “unsustainable” consumption of wealthy countries does to the global poor, and at the same time broadly condemns the technological advances and political and market institutions that have made that wealth possible.

This view of the situation is deeply flawed. Despite Pope Francis’s intention to propose actions that will benefit the poor, his sweeping condemnations of markets and technology and his proposals for climate policy are more likely to keep the global poor in their current state or make them worse off than they are to help alleviate poverty. Even the encyclical itself recognizes that the measures it endorses will increase the cost of energy where they are adopted, and that increases in energy costs are regressive — that is, that they harm the poor more than the rich. Furthermore, the encyclical acknowledges that it is doubtful that any measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would improve the plight of the global poor during their current lifespans, because reducing emissions will have no effect on the climate-related disasters currently plaguing them, such as droughts and floods. It will take at least several decades for even drastic reductions in emissions to make any difference to global temperatures.

The flaws of Laudato Si’ are not in its statements about the ends we should strive for — to help the poor most affected by climate change and to properly care for the natural goods we share — but in its choice of means for achieving them. Thankfully, the encyclical’s proposals are not logically tied to its moral basis for action — principles of Catholic social thought that include respect for the human person, the common good, improving the plight of the poor, and solidarity with past and future generations. Indeed, the encyclical could have taken a different route based on these principles, if it had recognized the key role of economic and political freedom in promoting economic growth in even the poorest countries. This route would demand support for private-sector investments in poor countries that would increase their adaptability to climate change and reduce their vulnerability to natural disasters, combined with consistent advocacy and support for the changes in their political and economic systems that are necessary to produce sustained economic growth. Those changes must occur within the developing countries; to focus instead only on slowing economic growth or reducing carbon emissions in the more developed world will harm the poor rather than help them.

In looking for concrete recommendations for action, the reader of the encyclical finds two quite different approaches. One approach proceeds from a discussion of consumerism, technology, and scarce resources and sees only a drastic reduction in rates of economic growth as sufficient to avoid catastrophe. The second approach is conventional and relatively pragmatic, addressing policies to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy and international negotiations to impose binding limits on greenhouse gas emissions. This essay will take up both approaches and their respective problems in turn.

Growth Beyond Limits

Laudato Si’ claims that the roots of the ecological crisis have to do primarily with economic and technological growth. Resources are limited, the argument goes, which means that the present levels of consumption and waste in developed countries are unsustainable. “The exploitation of the planet has already exceeded acceptable limits and we still have not solved the problem of poverty.” Technology, which has provided many benefits and about which “it is right to rejoice,” is itself also part of the problem. Quoting Pope John Paul II’s 1981 address to scientists, Pope Francis writes that “science and technology are wonderful products of a God-given human creativity.” But technology has also served a rampant consumerism by providing goods that are not needed and supporting a business system that encourages unnecessary levels of consumption. In one example that many commentators have jumped on, Pope Francis mentions the “increasing use and power of air-conditioning. The markets, which immediately benefit from sales, stimulate ever greater demand. An outsider looking at our world would be amazed at such behaviour, which at times appears self-destructive.”

But the roots of the problem concerning technology are even deeper, the encyclical explains. We operate in a “paradigm” that “exalts the concept of a subject who, using logical and rational procedures, progressively approaches and gains control over an external object.” This attitude of manipulation of the world around us “has made it easy to accept the idea of infinite or unlimited growth, which proves so attractive to economists, financiers and experts in technology. It is based on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the earth’s goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry beyond every limit.”

Furthermore, the effects of over-consumption and the over-exploitation of resources are made dramatically worse by the fact that the global population is growing. Pope Francis writes that some people falsely imagine that the only solution is a reduction in birth rate, while ignoring that the real issue is the “extreme and selective consumerism on the part of some.” Blaming population growth instead of consumerism “is an attempt to legitimize the present model of distribution, where a minority believes that it has the right to consume in a way which can never be universalized, since the planet could not even contain the waste products of such consumption.”

The encyclical concludes that the solution to this set of problems at the heart of the ecological crisis — involving economic and technological progress, consumerism, and population growth — is to restrain economic growth in some countries so that it can develop in others.

If in some cases sustainable development were to involve new forms of growth, then in other cases … we need also to think of containing growth by setting some reasonable limits and even retracing our steps before it is too late. We know how unsustainable is the behaviour of those who constantly consume and destroy, while others are not yet able to live in a way worthy of their human dignity. That is why the time has come to accept decreased growth in some parts of the world, in order to provide resources for other places to experience healthy growth.

This means, Pope Francis explains, that we stop being content with trying to balance the protection of nature with economic and technological progress; rather, “it is a matter of redefining our notion of progress. A technological and economic development which does not leave in its wake a better world and an integrally higher quality of life cannot be considered progress.” All too often, economic growth involves a lower quality of life, for instance when the environment is harmed and food quality drops. Instead of talking about “sustainable growth,” which “usually becomes a way of distracting attention and offering excuses,” we need to rethink the meaning of progress itself and find ways to correct the flaws of our current economic system.

We need also to “reject a magical conception of the market,” according to which profit incentives for companies or individuals could help abate the ecological crisis. “Is it realistic to hope that those who are obsessed with maximizing profits will stop to reflect on the environmental damage which they will leave behind for future generations?”

Misunderstanding Markets

While the moral intent of the encyclical’s critique of the market and of consumerism is well worth our attention — more on this later — its economics are dangerously false. Even if, following Pope Francis’s logic, the wealth of the poorest rises for a time while that of the richest declines, there will come a day when incomes of the rich and poor have leveled out. From then on, there is no direction for global wealth to go but down. The logical conclusion is that, as long as resources are limited and population increases, the only possible future is of an inexorable decline of wealth per person.

This is precisely the progressive immiseration that Thomas Malthus foresaw: When each person’s share of the Earth’s resources falls below the level necessary to sustain life, the result is starvation and an end to population growth due to rising death rates. This cannot be a future that the Holy Father intends, but it arises directly from his contentions about resources, growth, and technology.

Fortunately, Malthus’s forecast has failed, because the market systems and technological innovations that Pope Francis questions have succeeded in creating sustained income growth in all the countries where they took hold. This fundamental blindness to the roles of technological change and the market economy in the history of material progress is the central failing of how Laudato Si’ treats environmental policy.

The encyclical rejects the possibility that a market economy can reduce pollution through policy and regulation, and suggests that environmental degradation will become worse and worse unless entirely different economic systems and models of economic growth are adopted. This conclusion derives from a misunderstanding of how markets can be regulated to deal with pollution and other environmental effects, a distorted view of political economy in the major economies of the global North, and a consistently pessimistic view of environmental trends.

The economic theory that the encyclical takes to task is a straw man — a distorted version of market economics in which no government intervention is ever needed for markets to produce socially and ecologically beneficial conditions: “Some circles maintain that current economics and technology will solve all environmental problems, and argue … that the problems of global hunger and poverty will be resolved simply by market growth.” While some people certainly subscribe to such a theory, it is not how current market economies work in reality. In fact, advanced market economies have adopted effective policies to improve air and water quality, to control misuse of toxic substances and wastes, and to manage land use. The result of these measures, which have been applied vigorously and systematically in the United States since the 1970s, has been a combination of both sustained economic growth and reduced environmental damage.

Consider the evidence: Average concentrations of particulate matter in the United States have been cut by 40 percent since 1988. Peak ozone concentrations have been cut almost in half since 1980, and ozone levels in the smoggiest city, Los Angeles, are about 40 percent of what they were in the mid-1970s. The nation’s average emissions of sulfur dioxide have been cut by 80 percent since 1980, while emissions of nitrogen oxides have been cut by more than half, and carbon dioxide emissions per capita are the lowest since 1964. All of these improvements occurred with the help of regulatory programs and market incentives, while the economy grew robustly. For instance, according to a 2015 report on California’s air quality, since 1990 the state’s population and registered vehicles have each grown by about 30 percent and the economy by over 80 percent, while toxic emissions have decreased by 80 percent and smog-forming emissions have been cut in half.

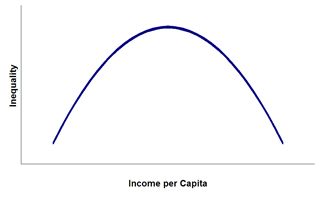

The Kuznets curve is a graph depicting the economic hypothesis that as market forces develop income inequality first increases before decreasing.Princess Tiswa / Wikimedia [CC] There is even a strong correlation globally between economic development and performance in reducing certain kinds of environmental damage, such as from emissions. This relationship — dubbed the “environmental Kuznets Curve” — is represented in a graph with an inverted U shape. In poor countries, the first stages of economic growth involve increasing emissions; during the transition to the middle-income range, countries’ emissions level off; and as countries reach high-income status their emissions begin to decline. Whether this is due to a change in the structure of economies as they grow or to changing preferences of their citizens to embody more “post-materialist” values, the result is the same: income growth is related to a decline in environmental harm.

The Kuznets curve is a graph depicting the economic hypothesis that as market forces develop income inequality first increases before decreasing.Princess Tiswa / Wikimedia [CC] There is even a strong correlation globally between economic development and performance in reducing certain kinds of environmental damage, such as from emissions. This relationship — dubbed the “environmental Kuznets Curve” — is represented in a graph with an inverted U shape. In poor countries, the first stages of economic growth involve increasing emissions; during the transition to the middle-income range, countries’ emissions level off; and as countries reach high-income status their emissions begin to decline. Whether this is due to a change in the structure of economies as they grow or to changing preferences of their citizens to embody more “post-materialist” values, the result is the same: income growth is related to a decline in environmental harm.

Why Are They Poor?

Perhaps the main reason the encyclical misrepresents how a market economy can respond to environmental problems and to poverty is that Pope Francis does not envision a free-market alternative to the “crony capitalism” that plagues many Latin American countries, as well as China and Russia, to name some extreme examples. Here is how he describes the working of politics today:

Often, politics itself is responsible for the disrepute in which it is held, on account of corruption and the failure to enact sound public policies. If in a given region the state does not carry out its responsibilities, some business groups can come forward in the guise of benefactors, wield real power, and consider themselves exempt from certain rules, to the point of tolerating different forms of organized crime, human trafficking, the drug trade and violence, all of which become very difficult to eradicate. If politics shows itself incapable of breaking such a perverse logic, and remains caught up in inconsequential discussions, we will continue to avoid facing the major problems of humanity.

With all of the faults of the American economic system, its performance is not nearly as bad as this description of crony capitalism, in which private property and economic opportunity are reserved for the political elite, and in which violence and civil unrest occur repeatedly. It is the correction of these conditions, not the rejection of economic freedom, that is necessary to lift countries from poverty.

This corresponds with the predominant view among experts in economic development, which is that the structure of a society’s institutions is the most important determinant of whether that society will be able to achieve sustained income growth per capita. According to this position, the main reason for poverty in the global South is not environmental damage, resource poverty or exploitation, or ecologically harmful actions of the industrial world. Most poor countries remain in poverty because they are ruled by coalitions that exclude any but their favored members from access to markets, from secure ownership of land and property, and from participation in organized politics. By doing so, the rulers can capture whatever economic surplus their country can generate, and use that wealth to buy the support that they need to retain power. (Notable dissenters from this mainstream view include Jeffrey Sachs and Jared Diamond, who tend to focus on geography, not politics, for explaining poverty.) By contrast, in countries where the barriers to entering markets and politics are low, freer markets spur economic growth, and more open politics limit the scale of destructive rent-seeking. The economy grows, and growth legitimates the society’s institutions.

Far from causing harm around the world, growth in industrial countries creates markets for exports and provides foreign direct investment that has contributed to income growth in countries with open access and favorable investment climates. A market-based approach to helping the global poor suffering from climate change would require policies and institutions in their countries favorable to investment in infrastructure, agriculture, and other areas where vulnerability can be reduced, the basis for which needs to be economic freedom and property rights. Throughout Laudato Si’ there are moments when Pope Francis seems to recognize how these prerequisites for economic growth are related to the inherent dignity of persons created in the image of God, but they are overwhelmed by questionable theories of the failure of markets and technologies and of limits to growth.

More open societies also adapt better to change, including the challenge of climate change. In its fifth report, published in 2013 and 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) explains that “Adaptation constraints, particularly pronounced in developing countries, result from lack of access to credit, land, water, technology, markets, information, and perceptions of the need to change.” Also, reducing vulnerability to climate change and increasing the ability to adapt is especially challenging “in regions that have shown severe difficulties in governance.”

However, the process of opening markets and political systems to freer entry can be destabilizing. Violence may ensue, and it can forestall and even reverse the emergence of a stable open-access order, as happened in the 1990s when political reforms in Rwanda, Burundi, and other African states were followed by horrific civil wars. The authors of Violence and Social Orders (2009) estimate that only 15 percent of the world’s population lives in countries that have adopted the full logic of open access. And as William Easterly observes in The White Man’s Burden (2006), financial assistance given to countries with corrupt regimes tends to enrich those countries’ elites, rarely achieving any of its intended purposes for the poor.

Pope Francis recognizes the baleful influence of corruption, crony capitalism, and government by exploitative elites. For example, he writes that “For poor countries, the priorities must be to eliminate extreme poverty and to promote the social development of their people. At the same time, they need to acknowledge the scandalous level of consumption in some privileged sectors of their population and to combat corruption more effectively.” The value of this type of condemnation should not be ignored just because it is incorrectly extended to all market economies. But it could have led to a more explicit warning about the folly of supporting exploitative regimes, which the encyclical fails to provide.

Emissions and Poverty

The encyclical is not only shortsighted in its view of what market economies can do to help alleviate both poverty and environmental damage; its recommendations for climate policy are similarly myopic. Pope Francis explains that “the Church does not presume to settle scientific questions or to replace politics” and that “the Church has no reason to offer a definitive opinion” on the various policy proposals that are possible. Accordingly, the encyclical offers only general recommendations, not detailed proposals. But these recommendations are all run-of-the-mill — including support for renewable energy and phasing out the use of fossil fuels — and they show a preference for command-and-control regulation over market-based approaches to climate policy, such as emission trading systems. The encyclical strongly endorses international agreements both to help reverse global warming and to reduce poverty: “A more responsible overall approach is needed to deal with both problems: the reduction of pollution and the development of poorer countries and regions.” The global economy has weakened the power of national politics so that it is now “essential to devise stronger and more efficiently organized international institutions, with functionaries who are appointed fairly by agreement among national governments, and empowered to impose sanctions.”

Furthermore, the encyclical endorses the notion of “differentiated responsibilities” — the idea that countries that have benefited from industrialization and that have therefore produced a greater amount of emissions are responsible for reducing their own emissions first and funding efforts by developing countries to reduce theirs.

But what effect does reducing emissions have on the global poor? There are two points to consider: first, the economic effect on the poor, which will be felt immediately, and, second, the effect on the climate — a long-term process that one hopes would benefit the poor in future generations. In both cases, the encyclical does not sufficiently acknowledge that the poor today would not benefit from reducing emissions, and that the long-term effect on the climate is far from guaranteed.

Pope Francis recognizes that actions to reduce emissions in poor countries, such as switching to environmentally friendlier fuels, “would risk imposing on countries with fewer resources burdensome commitments to reducing emissions comparable to those of the more industrialized countries. Imposing such measures penalizes those countries most in need of development.” But this leads in the encyclical only to a recommendation that industrial countries shoulder the extra cost, not a broader strategy for reducing poverty. And if rich countries pay poor countries to phase out fossil fuels and to adopt alternative sources of energy, such a move will do nothing for the current plight of the poor. Indeed, since non-fossil fuels are more expensive than fossil fuels, the poor will be stuck with higher energy costs after the transition than before — unless those costs are also subsidized by rich countries.

Nor will a transition to renewable energy benefit the poor in wealthy countries. As has been pointed out in criticisms of the EPA Clean Power Plan — and admitted by EPA administrator Gina McCarthy — requiring utility companies to abandon use of their least costly fuel, coal, will drive up electricity rates and cause disproportionate harm to the poor for whom those bills are a higher share of their income than for the rich.

There is yet another way in which higher energy costs in countries reducing emissions harm the global poor: they would raise the price of goods imported by poor countries for consumption and for building industries. (This would occur also if richer countries were to restrain their growth, as the encyclical proposes.)

Laudato Si’ recognizes that strategies that only address emissions will not aid the poor for some time: “since the effects of climate change will be felt for a long time to come, even if stringent measures are taken now, some countries with scarce resources will require assistance in adapting to the effects already being produced, which affect their economies.” But the encyclical never follows up on this insight.

If wealthy countries wished to help lift poor countries out of poverty, a far better course would be to invest in infrastructure to improve the adaptability and flexibility of weak economies, and to invest in local entrepreneurs and businesses that would lead to sustained income growth per capita. But should wealthy countries choose to assuage their consciences by pouring money into renewable energy in poor countries, there is likely to be little left for these other, more effective forms of poverty reduction.

The second point — about the effect of reducing emissions on the climate — is of course scientific, not economic. Pope Francis explains that “gas residues … have been accumulating for two centuries and have created a situation which currently affects all the countries of the world…. The warming caused by huge consumption on the part of some rich countries has repercussions on the poorest areas of the world, especially Africa, where a rise in temperature, together with drought, has proved devastating for farming.”

But this overstates the effect of human activity on current conditions. The IPCC itself puts low confidence in any attempt to say that human contributions are responsible for the increase of extreme weather events such as droughts and tropical storms. Thus, the present suffering of poor countries from natural disasters cannot be cured by reducing emissions in industrial countries; indeed, reducing emissions in industrial countries will not change the prevalence of those disasters for many decades, if at all.

Moreover, the IPCC explains that both in a high-emission and a low-emission scenario, “projected global temperature increase over the next few decades is similar.” This is because it takes many decades for changes in emissions to show up in changing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The report proceeds to state that “societal responses, particularly adaptations, will influence near-term outcomes.” Only in the second half of the twenty-first century and beyond will emission reductions have any effect on global temperatures. Thus it is only thirty-five years or more in the future — probably beyond the average lifespan of the poorest now living — that any action on emissions could mitigate the harmful effects of temperature increases on the global poor.

But what about the future? Might not emission reductions undertaken today by wealthy countries help alleviate the suffering of the poor of tomorrow? Unlikely. The rapid growth in incomes and emissions in countries that are currently not rich but rapidly growing will make them responsible for the large portion of future emissions. In a 2012 report, the OECD noted that Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa (the BRIICS countries) today account for about 40 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions, up from 30 percent in the 1970s. Carbon dioxide emissions per capita in these countries are expected to double between now and 2050 (although they would then still be lower than in OECD countries).

Even if wealthy countries eliminated their emissions, currently forecast emissions from the other countries would still drive the increase in temperature over the threshold of 2 degrees Celsius that many consider to be the maximum that can be tolerated without heightened risks. The IPCC report estimates that this threshold can likely be avoided if, by the year 2050, human-induced greenhouse-gas emissions are 40–70 percent lower than they were in 2010, and if, with the help of carbon-dioxide removal technologies, emissions levels are “near zero or below in 2100.”

Needless to say, current international negotiations fall short of this ambitious goal. And where Laudato Si’ seems to envision a top-down approach to establishing global limits on greenhouse-gas emissions, negotiations have shifted toward a more bottom-up approach to help avoid bargaining over emissions limits. In preparation for the United Nations climate change conference in Paris in December 2015, each country was asked to submit “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs) describing its best offer for reducing future emissions. By the start of October 2015, INDCs were submitted representing 146 countries, including the BRIICS countries, showing a concerted global effort to reduce emissions over the course of this century. But, as a U.N. analysis explains, even if all these INDCs were fully implemented, the expected increase in global average temperature would still likely be around 3 degrees Celsius by 2100, unless countries adopt even stricter measures in the coming decades.

Political and economic realities will make such dramatic emissions reductions highly unlikely. The BRIICS countries, despite their stated intentions, can be expected to act in their national interests — prioritizing economic growth and relying heavily on fossil fuels. For example, as an article in the Washington Post explains, India’s pressing need to generate electricity for the large portion of its population that currently lacks it will conflict with the country’s stated goals of reducing emissions. At the same time, the wealthiest nations have little national interest in dealing with climate change, since their wealth and geographic location make it much easier for them to adapt to any effects that climate change might have. That leaves only generosity as a basis for action on climate change on behalf of the global poor, and there is little history of generosity in matters of international relations.

None of this is to say that emissions reductions are futile altogether. But they are futile for helping the global poor — those currently alive as well as the next few generations at least. While Catholic social teaching provides a firm moral foundation for helping the poor, the recommendations on climate policy in Laudato Si’ sadly miss the mark.

A Spiritual Transformation

In spite of the flaws in its economic and policy reasoning, Laudato Si’ provides a much-needed moral case against consumerism, arguing for the kind of spiritual transformation that would support action on behalf of the poor and of our common home. Pope Francis begins the last chapter of the encyclical with the admonition that “it is we human beings above all who need to change. We lack an awareness of our common origin, of our mutual belonging, and of a future to be shared with everyone.” He recognizes that even the best policy proposals, laws and regulations, and enforcement of them are not enough to curb wastefulness and ecologically destructive behavior. “Only by cultivating sound virtues will people be able to make a selfless ecological commitment.” A change in individual hearts and minds is needed, which is a challenge for education in families, schools, churches, and other public and private institutions. Simple, daily acts of consuming less than we could, of limiting our water use to what we really need, of cooking only as much as we can eat — these acts of virtue may have little instrumental rationale but still “call forth a goodness which, albeit unseen, inevitably tends to spread.”

Using more theological language to address the Church specifically, Pope Francis reflects on the importance of the notion of nature as creation, which is to say, as a gift that is continually dependent on God. Forgetting this dependence leads us to believe we have an “unlimited right to trample his creation underfoot.”

Enjoyment of the natural, material goods God provides must always be tempered by the knowledge that they are gifts. Pope Francis’s condemnation of materialism, consumerism, and exploitation — harming nature and the poorest among us — arises from this teaching about nature as a gift and about our dependence on God who continually gives it. This orientation creates room for gratitude, charity, solidarity, and appreciation of goods of nature that we can never truly own.

With this moral and spiritual framework, together with a number of other elements present in the encyclical, a more constructive approach to climate policy would have been possible. Pope Francis emphasizes the need of the poor for work and that aid can only be a temporary solution. He recognizes that the poor in developing countries will be harmed if Green ideology forces them to pay for more costly energy to reduce emissions. He sees clearly that the effects of his preferred measures to reduce global temperatures will be slow and that poor countries will still need help in adapting. And he clearly understands how corruption, lack of access to markets, expropriation of property, and exploitation by political elites sustain poverty.

Thus the commandment to love thy neighbor and to “‘till and keep’ the garden of the world” that pervades the encyclical needs to be combined with a more accurate historical perspective on technology and the conditions that promote economic well-being, and a recognition of how income growth and environmental health can go together. Such a perspective would lead to strong advocacy of regime change in corrupt countries and of private-sector investment that would aid in reducing their vulnerability, because the most effective way to lessen the harm from natural disasters, whether due to climate change or other causes, is through improvement in the resilience and adaptability of vulnerable populations. This approach might also be embodied in strong instructions to contribute more to charitable organizations, such as Catholic Relief Services, that are effective in bringing about change in the right direction at the local level. In addition, a moral transformation of citizens and leaders is required to achieve global change, not world government and planning. That is the most important message of Laudato Si’; it is not an easy gospel of wealth but a message of placing our material interests in proper relation to God.