This essay is accompanied by the New Atlantis critical edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “The Artist of the Beautiful.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne is not an easy sell for present-day readers. Those who know him only through their high-school American Lit class’s forced march through The Scarlet Letter — which they very likely found to be a haunted house of archaic and spidery prose, slow-as-molasses plotting, implausible dialogue, and relentless moral sternness — may be inclined to dismiss him as a period piece, a moldy relic of mid-nineteenth-century New England, and have nothing more to do with him. Such a conclusion, though understandable, would be a grave error.

In fact, his fictions are proving to be astonishingly lasting with the passage of time, addressing themselves to situations and issues that have become far more exigent in the twenty-first century than they ever were in his own age. His stories are not merely fanciful — they are prophetic. They probe deeply and tellingly into the riddles that confront us at every turn in the modern day, riddles that have arisen out of our growing power over the physical world, and out of our perplexity in discerning what we ought to do, and not do, with such power. Hawthorne insists that we view our burgeoning power in terms very different from those in which it is usually celebrated. While not exactly an enemy of progress, he is certainly a committed skeptic. Hawthorne’s elaborately wrought fictions seem designed to reconnect us with a great mythic narrative at the foundation of the Western intellectual and moral tradition: the ultimate cautionary tale of how the acquisition of worldly power beyond one’s ken, and the transgression of venerable taboos and ancient boundaries, will surely lead to physical and moral ruin. This is the old, old story, told often and variously, in both Athens and Jerusalem, in texts both pagan and Biblical, of Prometheus, Icarus, Gyges, Babel, Eden, Lucifer, Faust, and countless others. Hawthorne’s irony-filled allegories and fables, with their constant reversals and inversions, evoke once again the mystery and terror of these ancient tales. To be sure, Hawthorne’s stories are also modern and acutely self-conscious, reflecting the peculiarities of their author. But like all the greatest fictions, their reach far exceeds the particularities in which, and for which, they were composed. They offer us today profound and prescient warnings about the many moral perils entailed in human efforts to gain mastery over the terms of human existence.

Of none of Hawthorne’s tales is this more true than his 1844 short story “The Artist of the Beautiful,” which would later appear in the 1846 collection Mosses from an Old Manse. Clearly Hawthorne was thinking along those very lines when he jotted the following story idea in his journal in 1837: “A person to spend all his life and splendid talents in trying to achieve something naturally impossible — as to make a conquest over Nature.” Whether this sentence fragment was the source from which “The Artist of the Beautiful” emerged seven years later is impossible to know for certain. But we do know that Hawthorne’s words in his journal describe the story that “The Artist of the Beautiful” turned out to be.

At the center of the story is a splendidly talented young man, the diminutive, reclusive, unprepossessing, and socially maladroit Owen Warland. Even Owen’s detractors, chief among them being his former employer, the watchmaker Peter Hovenden, are willing to acknowledge this young man as the possessor of an “irregular genius” and “delicate ingenuity,” which had manifested itself from very early in life in an unusually developed ability to work with objects on a tiny, even microscopic scale. Such an unusual talent naturally suits him for the close and careful labor of the watchmaking trade; hence his early apprenticeship to Peter Hovenden. Yet when Owen takes over Peter’s business, he finds himself bored with it, and is instead obsessed with the creation of a delicately calibrated nature-defying mechanism whose precise identity is not revealed until the story’s close. He works on this secret mechanism night and day for months on end, to the neglect of his business and the dismay of his neighbors and customers. The story relates how fervently he persists in this quixotic mission despite numerous calamitous setbacks and the near-universal incomprehension and disdain of his own community, even of those whose opinion he cherishes.

It is never entirely clear how Hawthorne means us to react to this remarkable character. On the one hand, we are clearly supposed to admire Owen, for his single-mindedness and determination, for his creative energy and brilliant ingenuity, and for his disinterested and almost selfless dedication to the beautiful. We are told of the wooden figures he carves with his delicate hands, “figures of flowers and birds” which “seemed to aim at the hidden mysteries of mechanism,” figures made with no objective in mind beyond “purposes of grace.” Beauty is for him an end in itself, the highest of all ends, whose sanctity he guards with the loving ferocity of a Marian pilgrim. There is, in short, a purity of heart and singleness of will at work in Owen. He desires to create beautiful things not to conquer the world or to make himself all-powerful, but only to make visible, and animate, certain perfections whose possibility he alone has been granted the power to intuit.

On the other hand, we also sense that Hawthorne shares some of the views of the townspeople, and sometimes loses patience with the airy-fairy quality of Owen’s mind. “One of his most rational projects,” writes Hawthorne, tongue more than a bit in cheek, “was to connect a musical operation with the machinery of his watches, so that all the harsh dissonances of life might be rendered tuneful, and each flitting moment fall into the abyss of the past in golden drops of harmony.” Hawthorne too shares in the feeling that Owen can be flighty and immature — “he was full of little petulances” — and that there might be something hopelessly grandiose and childish about Owen’s ambitions, and something life-wasting about these intense, minute labors that drain all his talent into the production of something chimerical, something downright contrary to nature itself.

Some of the ambivalence may reflect the fact that Owen Warland seems to be, at least in some respects, a stand-in for Hawthorne himself, manifesting Hawthorne’s own ambivalences about his choice of an artist’s career. After graduating in 1825 from Bowdoin College, where his friends had included such high achievers as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Franklin Pierce, he mysteriously chose not to pursue any of the career paths open to a man of his education and station. Instead, he would spend the next twelve years living in his mother’s house in Salem, willingly cut off from the world of commerce and public affairs, concentrating all his energies on the development of his writerly craft rather than the development of a practical trade — and all the while being tormented by just the sort of self-doubt that such a decision would be likely to engender in most any man of his day. As he finally described it in an 1837 letter to Longfellow, written at the very moment he was screwing up his courage to rejoin the world, it seemed to have been “by some witchcraft or other” that he had been “carried apart from the main current of life.” He never intended to do what he had done, he said, and yet somehow it had happened. “I have made a captive of myself,” he cried, “and put me into a dungeon; and now I cannot find the key to let myself out — and if the door were open, I should be almost afraid to come out.”

In making such a pathetic declamation, Hawthorne sounded very much like one of his own characters. And his creation of a few years later, Owen, turns out to be very much like him in this regard, as an isolated poet manqué, fabulously talented but completely lacking in conventional bourgeois ambitions, ill-suited to his functional watchmaker’s job, disdained by the stolid and pragmatic-minded burghers in the surrounding community as a dreamy and impractical man-child whose chief goal in life seems to be the production of entirely useless things.

There are, to be sure, obvious and important differences between the author and his subject. Owen is a craftsman and engineer and inventor rather than a painter or novelist. Yet there can be no doubt that we are meant to see him as having the soul of a romantic artist par excellence. Owen is rightly called an “artist of the beautiful”: In wishing to produce only things that are beautiful in themselves, things that must be fashioned without any view whatsoever to their utility, he carries the romantic artistic temper to its most gaudy, breathtaking, and inflexible extreme. From the community’s point of view, this is the attitude of a narcissistic and self-absorbed adolescent who refuses to grow up and assume the responsibilities commensurate with an adult life. His very name, “War-land,” expressing the battlefield of his psyche, hints that he is an embodiment of the same torments of indecision that had racked Hawthorne for so many years.

The story begins with a vivid contrast that frames the rest of what is to come. Peter Hovenden and his daughter Annie are strolling down a street in their town one gloomy evening and encounter two very different places of business. First they peer into the window of Owen’s watch-repair shop, which used to be Peter’s own place of business, but which has under Owen’s management become a strange cove, a site for hermetic withdrawal and delicate but frenetic industry. The interior of the shop is illuminated chiefly by Owen’s work lamp, under whose concentrated light he labors with steady, near-fanatical intensity, although it is clear to Peter that the object of Owen’s labors is not a timepiece. Owen proves to have little regard for such things. In one of Hawthorne’s wonderful touches, we are told that all of the beautiful watches on display in the shop window have had their faces turned away from the street and into the interior — a perfect figure of the shop’s master himself, both in his introspection and his utter hostility to any useful aspect that a beautiful thing might evince. Peter cannot contain his disgust, and expresses his exasperation with Owen’s penchant for “foolery,” his waste of time and talent, while Annie defends Owen, though to little effect.

Leaving Owen’s shop, the father and daughter walk for a while and finally come to the blacksmith shop of the robust and manly Robert Danforth. The contrast could not be more vivid. Through Danforth’s open door they see him hard at work, the light of his blazing forge pulsating with the rhythm of the gasping bellows, alternating between a surge of fiery expansion followed by a diminuendo of air-inhaling contraction, then followed by another bright blast: a powerful, primal, furnace-like image expressing not only the hearty rigors of physical labor, but the robust systolic and diastolic alternation of nature itself. Danforth’s workshop has the beating heart and breathing lungs of a living thing; it is a very practical machine that also mimics the ways of nature.

The implied contrast to Owen’s ethereality and hermeticism could not be more pointed. We understand that Robert Danforth is a more “natural” man; he is a man of action and practicality, of animal faith and confident instinct, who represents the commonsense sanity of the useful life. There are even hints in his character of the Greek god Hephaestus, the blacksmith-artisan god of craft and technology, and in that sense Danforth too is being represented as an artist — not an artist of the beautiful, but of the useful. As Peter Hovenden says, admiringly, he “spends his labor upon a reality.” By contrast, Peter dismisses Owen as a silly boy transfixed by the allure of “ingenuity,” and by fantastical notions which would “turn the sun out of its orbit and derange the whole course of time.” One could say, without irony, that Peter has no use for such a man. Nor can there be any doubt which of the two he would prefer as a son-in-law and a husband to Annie.

In all fairness, there seems to be something deeply and disturbingly unnatural about Owen, including even his relationship to the proper ends of human technology. And it actually is very hard to argue with the virtues that Peter Hovenden commends. Who could disagree that “it is a good and a wholesome thing to depend upon main strength and reality, and to earn one’s bread with the bare and brawny arm of a blacksmith”? Is this not a home truth, affirming the central value of productive labor in our moral lives? And is there not something extreme, ineffable to the point of absurdity, and priggishly fastidious and self-absorbed to boot, about Owen’s insistence that his “delicate ingenuity” — which all agree is remarkable — should only be put to use “for purposes of grace, and never with any mockery of the useful…. completely refined from all utilitarian coarseness”?

There are, in fact, suggestions here and there of a streak of extreme romantic anti-industrialism in Owen’s views. He is horrified by the steam engine, as well as by most ordinary machinery and even the use of water power. He regards the suggestion that his secret “project” might be the discovery of a perpetual-motion machine to be grossly insulting, the equivalent of asking him to invent “a new kind of cotton machine” — presumably referring to the cotton gin. In any event, he would want no part in the making of such a contrivance.

Such attitudes make Owen extremely ill-cast as a keeper of timepieces, despite his evident dexterity with minute and delicate things. For the mechanical measurement of time is the very epitome of the useful, since its rational ordering of time is the essential grid upon which so much of modern industrial life, with its endless schedules, plans, and itineraries, is plotted. Such devices do more than measure time; they change time’s nature, bringing into being the very kind of time that is to be measured. The mechanical timepiece creates a hard and fast distinction between our natural experience of time, derived from the diurnal pattern of sunrise and sunset, and the rigid and relentless pattern of modern time. As such, the mechanical timepiece is a powerful symbol of the colonization of the life-world by the imposition of a universal temporal standard, the intrusion into all corners of life of the empire of industry and machinery and standardization, all for the sake of utility rather than beauty.

Owen is likely to see the matter in just this way, and his having such attitudes sets him at odds with his own clientele. The “steady and matter-of-fact class of people” who care about their clocks hold that “time is not to be trifled with,” and do not appreciate Owen’s whimsical additions to their sober and practical timekeepers. These are the people for whom the slogan “time is money” amounts to one of life’s guiding precepts. But Owen cares little about either thing, and thereby leaves himself in an exceedingly uncomfortable position. To make his profession the repair of watches is to prop up the very order of things against which he so heartily rebels. It means living life as if he were a vegetarian in a slaughterhouse, in exile from his element, in daily violent opposition to his deepest convictions.

To make matters worse, we soon see that Owen is launched (just as Peter suspected) into a deep and secret project, something completely unrelated to his watchmaking, an undertaking of unimaginable complexity which utterly consumes his life, and which the reader is made to feel is almost certainly impossible to complete successfully. This project has for him the quality of a religious calling, a pilgrimage around which he has organized every aspect of his life and every fiber of his being. Yet he cannot share the details of the project or its objectives with anyone, for fear that any contact with outsiders will destroy his work. A paranoid-sounding fear, but it turns out to be justified. On every occasion in which he shows his work to someone, the work-in-progress proves too fragile to withstand examination, and is destroyed by being crudely mishandled — again, a symbol of the larger society’s coarse sensibility, and its incomprehension of the artistic mind. When this happens to Owen Warland, the artist of the beautiful, he collapses into despair and darkness. Perhaps it is, the narrator tells us with an ominous tone, the fate of all such lovely ideas to be “shattered and annihilated by contact with the practical.” The reader begins to wonder whether this hard and depressing piece of snake-bit wisdom is going to turn out to be the lesson that the congenital pessimist Hawthorne seeks to drive home with this story.

Add to these things Owen’s passionate but doomed love for Peter’s daughter Annie, for the sake of whom Owen claims that all his labors were motivated, over whom his heart palpitates uncontrollably whenever she is near, but whom he utterly lacks the ability to court plausibly or effectively, and whom he eventually loses when she takes the more practical and sensible route of marrying Robert Danforth the blacksmith — add all this in, and you have a recipe for a comprehensively failed life. Here too Hawthorne could see himself, vividly remembering his own long and lonely bachelorhood, his own futility and incompetence with women, and imagining what a woeful desert his own life would surely have become had it not been for the intervention of his own miraculous marriage. When he describes Owen’s feelings of separation from the multitude, resembling that of “the prophet, the poet, the reformer, the criminal,” and he thinks of “what a help and strength would it be to him in his lonely toil if he could gain the sympathy of the only being whom he loved,” Hawthorne surely knew whereof he spoke. Owen’s life represents all too vividly a road that Hawthorne himself could have traveled.

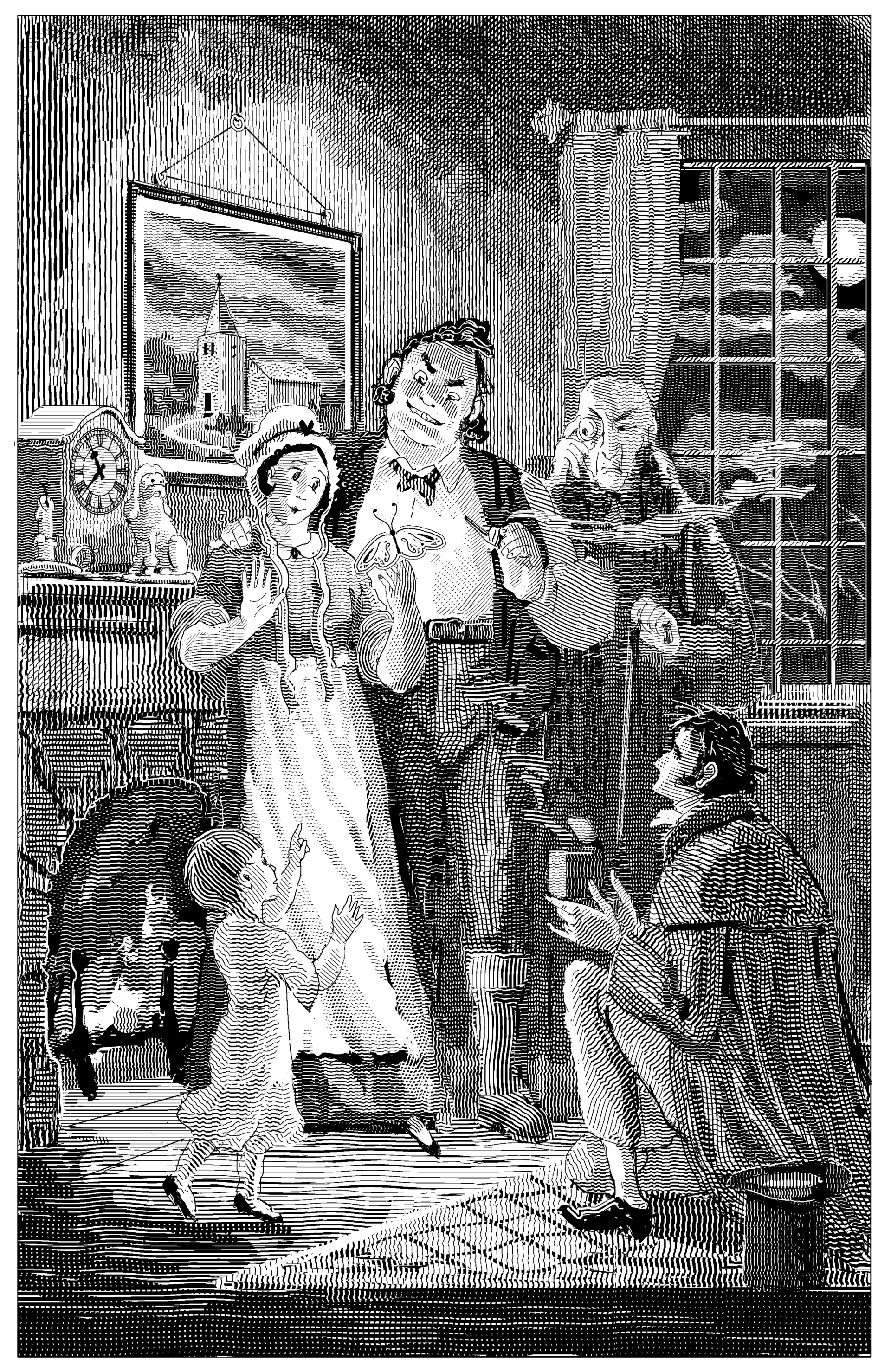

In the end, though, Annie deeply disappoints Owen, both in mishandling and misunderstanding his work-in-progress, and then later in marrying Danforth. The announcement of her engagement is so shattering to Owen that it causes him to abandon his great project. “He had lost his faith in the invisible,” says Hawthorne, and for a time the spirit “slept” in him. Eventually, however — though how it comes about is not explained — the spirit reawakens in him, and he regains the desire to return to his obsession and complete his project. At the story’s end, the momentarily triumphant Owen presents the Danforth family with his completed project, which turns out to be a wondrous mechanical butterfly that has taken on the attributes of a living being. The butterfly is indeed a thing of spectacular and numinous beauty, a heavenly apparition in the pattern of “those which hover across the meads of paradise for child-angels and the spirits of departed infants to disport themselves with.” Time seems to stand still as the Danforth family stands and stares, entranced by its magical presence, as it waves and flutters its purple and gold-specked wings and flits and soars around the room from person to person. “Well,” exclaims Robert Danforth, “that does beat all nature!” He perhaps does not realize how right he is.

And then the blow falls. It is Annie’s own infant son who destroys Owen’s finished creation, thoughtlessly crushing it in his hand. We understand at the moment it happens that the object’s re-creation is doomed never to be: this is it, finis, for Owen’s project. At that moment, it would seem that the entire story of Owen could be read as a pathetic tale of a talented man whose life became distorted by its dedication to a ridiculously grandiose and ultimately impossible project, one that defied nature in every way. That would seem to make the story a perfect fulfillment of the very words Hawthorne penned in that journal entry of 1837.

Giving the story added potency is the depth of Owen’s determination. He found himself repeatedly defeated, and with each defeat, he experienced an overwhelming sense of being “ruined.” And yet Owen never gets the message, never can accept the futility of what he is trying to achieve, never gives up for long. He always returns to his art. Is this admirable determination or sheer madness? Indeed, the structure of the story sometimes seems to nudge us toward much the same view of Owen that the townsfolk take: as a helpless and obsessive waif who is in some sense too delicate for this world, or who has been driven insane, whose mind is in the grip of hopelessly unrealistic notions, and whose little magic kingdom is doomed to be snuffed out, as all childish things are, by the larger forces that always prevail in real life.

Hawthorne continues to hint at his own subtle ambivalence toward Owen. In one particularly affecting passage, the narrator tells us that “the chase of butterflies was an apt emblem of the ideal pursuit in which [Owen] had spent so many golden hours; but would the beautiful idea ever be yielded to his hand like the butterfly that symbolized it?” The answer appears to be No. The artist of the beautiful, it seems, is the one who could not be content to enjoy the beautiful inwardly, but feels compelled to represent it externally, to “chase the flitting mystery beyond the verge of his ethereal domain, and crush its frail being in seizing it with a material grasp” — an image that anticipates the abrupt end to which Owen’s invention will come. Hence the story’s climax, in which the infant Danforth child (who seems to Owen to bear the hostile Hovenden countenance) reduces Owen’s transcendent artistry to “a small heap of glittering fragments, whence the mystery of beauty had fled forever,” is something entirely preordained by the nature of things, and the infant merely an instrument by which that larger necessity is realized. That this infant also embodies in his person the greater “naturalness” of Robert Danforth, a living and breathing expression of his fertile union with Annie, only drives home the point: nature humbles those who would challenge her frontally.

But Hawthorne is not finished yet, and we must read carefully to the very end if we are to grasp his real intent. To take away from the story the dismal message that the artist of the beautiful is doomed always to destroy the thing that he loves, or to see it destroyed by the hands of uncomprehending others, would be to mistake its meaning. We must take the full measure of the narrator’s final three sentences, which change everything, effecting an abrupt and stunning bouleversement that transforms the meaning of all that has come before. Here are those three sentences, coming right on the heels of cruel old Hovenden’s “cold and scornful laugh” directed at Owen’s plight, a moment that we might expect to be the nadir of humiliation for Owen. But it is not, and instead we get something entirely unexpected, a complete reversal:

And as for Owen Warland, he looked placidly at what seemed the ruin of his life’s labor, and which was yet no ruin. He had caught a far other butterfly than this. When the artist rose high enough to achieve the beautiful, the symbol by which he made it perceptible to mortal senses became of little value in his eyes while his spirit possessed itself in the enjoyment of the reality.

This ruin of his hopes was “yet no ruin”? And what is this “far other butterfly” he is said to have caught? The answers to these questions hold the key to the story’s meaning.

What Owen had been seeking all those years — and his Annie had been the one to put it into words for him — was “the spiritualization of matter,” the perfect sublimation of material crudity into spiritual grace, free of the encumbrances and limitations of the flesh, including the earthbound need for utility. The story’s recurrent imagery of the butterfly, one of the greatest and most universal symbols of transformation and spiritual rebirth, underscores the centrality of this search. It was a noble search that he had undertaken. Yet Owen had not understood until this final culminating moment that in all his efforts to wrest hold of the material world and compel it to express something purely spiritual, he had all the while really been working on something else, in another element, something entirely different from what he thought he was working on: He had been working on his own soul. Indeed, the transformation of the object of his labors from the one into the other is beautifully figured in the Greek word psyche, which means both “butterfly” and “soul.” Owen’s work was preparing him to take possession of his soul — that “far other butterfly” — in a full and immovable way, protected from the ravaging incomprehension of the world, free of the need to call upon the sanction or solicitude of other people to strengthen or confirm its hold on imperishable beauty.

Looking back over the story, we now see that Hawthorne has repeatedly prefigured this insight in small but telling ways. In each of Owen’s defeats, even the loss of Annie, he is crushed at first, but is eventually made stronger and more resolute, precisely because he is more able to detach the pursuit of his goal from other things to which that goal had attached itself — the love of a woman, the approbation of others, the prospect of worldly success — or even, as it finally turns out, from the actual persisting physical existence of the very thing he has labored to create. A glimpse of this insight is offered immediately after Owen’s troubling encounter with Robert Danforth had caused him inadvertently to destroy his ongoing work, and then to sit “in strange despair”:

It is requisite for the ideal artist to possess a force of character that seems hardly compatible with its delicacy; he must keep his faith in himself while the incredulous world assails him with its utter disbelief; he must stand up against mankind and be his own sole disciple, both as respects his genius and the objects to which it is directed.

This is an insight that meant all the world to Hawthorne himself, as he struggled to find his artistic voice and the confidence to use it boldly. He was giving expression here to a piece of hard wisdom that every artist and every writer must acquire if he is to be successful. The artist of the beautiful must have two seemingly opposite traits. He must have the extraordinary “delicacy” and sensitive insight that make him able to see more deeply than others into the conditions of life; and yet he must also have extraordinary strength and firm resolution, to “stand up against” those who would “assail” him, and undermine the independence and self-confidence requisite to his expressive honesty and freedom. Hawthorne understood firsthand the artist’s need to steel himself against debilitating self-doubt, in a career that was likely to be full of disappointments and misunderstandings and severe criticism. He wanted to be able to adopt the same disposition in his own career that Owen had finally come to embody. As setback after setback came Owen’s way, his consequent ability to possess the beautiful became paradoxically stronger — strong in a way that finally could never be denied him, never be taken away from him, and never depend on the vagaries of others.

Perhaps, in the end, it has even dawned on Owen himself that “the spiritualization of matter” he had sought for so long is not exactly what he had been after all those years. Instead, it is the capacity of the human soul to recognize the spiritual for what it really is, something he comes to understand only at the moment when his former ambitions are so roundly defeated. The problem with the spiritualization of matter is that in practice it turns out to be something like its opposite: not an effort to refine and elevate and exalt matter, but an effort to transcend the opposition of spirit and matter altogether, and make material that which belongs first and foremost to the realm of spirit. Such efforts may proceed from admirable intentions, but have paradoxical effects. For the comprehensive elevation of the material world would be indistinguishable from the materialization of the spirit, and a force tending toward the spirit’s diminishment.

Given the centrality of the imagery of butterflies in the story, it is hard to imagine that Hawthorne was not influenced in his thinking about these matters by a famous passage from the Sermon on the Mount, found in Matthew 6:19-20:

Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal: But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal: For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.

Jesus’ image of the “moths that corrupt” could be read as an ironic analogue to the earthly butterflies that Owen futilely chased in his youth, and that formed the pattern for his life’s quest. But it seems that by the time Owen has lost the one ultimate butterfly, the object of his many months of patient labor, he has already recognized it as yet another, more elaborate version of the “moth that corrupts” and dies. The “moth” capable of transcending corruption cannot be a material moth, no matter how ingenious or elaborate. It can only be an idea of the moth that, like a Platonic form, exists apart from any requirement that it be materially embodied. And it is in that far realm of the ideal, wherein “his spirit possessed itself,” that Owen, the artist of the beautiful, is ultimately at home.

In any event, the story clearly belongs in the pantheon of tales that caution us as to what happens when man proposes to “beat all nature,” or imagines that he can transcend her imperatives without incurring an unacceptable cost. Yet this story gives a slightly different inflection to those cautionary truths. In “The Artist of the Beautiful” we see a largely sympathetic character who struggles valiantly and selflessly against the ethos of crass utility and materiality that dominates his world. But in the end, what we see is that his struggle against that ethos fails: He cannot transform the world in any enduring way. And we see further that he cannot do so, not merely because it is so very difficult a task, but because it is a self-contradictory task, literally impossible, since it forgets that what is of the spirit is, and must remain, of the spirit.

And we see one more thing. Just as the brashly confident progressive ethos of the nineteenth century seemed to teach the inevitable triumph of the human will over nature, so it became Hawthorne’s peculiar mission to counter that conceit, and contend for the inevitability, and even the desirability, of that will’s defeat. That mission was important for reasons beyond the obvious. For, as this story indicates, some things are indeed “naturally impossible,” but defeat in one realm may be the necessary grounds for victory in another — that is, material defeat may be prerequisite to spiritual victory. Owen’s imperishable possession of the reality of the beautiful at story’s end, in a form that could never be effaced or taken away from him, represents a perfection that would never have been possible for him, had he not first striven with all his might, and failed, to embody that spiritual reality in a material form.

It was precisely his defeat in that regard that opened the door to the most enduring success that any lover of the beautiful could have ever wanted. Even as Peter Hovenden laughs cruelly in Owen’s face, at the very moment when we would expect Owen’s delicate constitution to crumble completely, Owen is placid and content. He is fully in possession at last, in a way that no external displacement can shake, of that “far other butterfly” of the spirit. His prior disappointments have been essential to his separating his love of “the beautiful” from everything else, including his beloved Annie, that was entwined with it. Hence, what could have been a culminating disaster for him becomes a moment of spiritual triumph and imperishable love; and the cruelty of Hovenden is unable to touch him. The peace Owen experiences at that moment, standing before his greatest detractor, is akin to the words of the Psalmist: “Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.”

We ought to keep in mind this insight about the “spiritualization of matter” — not only to the extent that we too aspire in our own ways to be artists of the beautiful in our lives, and live out the same kind of high calling as that to which Owen felt drawn, but also as we continue to think about the role of constant technological innovation in our mental and moral lives. The story has something to tell us about all these things. At their very best, all of our technologies seek to do precisely what Owen’s butterfly sought to do. They seek to spiritualize matter, to render time and space negligible, to override the limitations imposed upon us by nature, to eliminate the frictions and constraints assigned us by the peculiarities of our embodiment, by our mode of being in the world. The drive to do such things is irrepressible, an essential element in the dynamism of modernity and, perhaps, a drive lodged deep in human nature itself. And yet its results may not be unambiguously good. As we succeed more and more fully in bending the world to our will, we may be surprised to find that our doing so often begets unpredictable and seemingly inexplicable discontent and insecurity, the very things that such triumph was supposed to banish forever. If so, at least one reason for such discontent will likely be that we will have forgotten the lesson Hawthorne’s story teaches: that the relentless transformation of the recalcitrant material world into our frictionless and uncomplaining servant is not the same thing as the cultivation of the spirit. On the contrary, the “spiritualization of matter” may point to a condition in which the spirit becomes more fully than ever the prisoner of the flesh.

Material progress and the steady conquest of nature cannot change that fact. For it remains the case that spirit and matter are, and must be, different things. One of the many virtues of “The Artist of the Beautiful” is the way it reminds us of that fact — and reminds us that it takes failure and defeat and limitation, among other things, for us to understand the difference and learn to cherish it. Like Owen, we need to be rescued from our successes as much as from our failures. That will likely become more, not less, true in the years to come.