This essay is accompanied by New Atlantis critical editions of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short stories “Fire Worship,” “Earth’s Holocaust,” and “Ethan Brand.”

What I desire is man’s red fire to make my dreams come true….

Give me the power of man’s red flower so I can be like you.

From the ancient myth of Prometheus to the Biblical story of Babel to the modern children’s fable of Mowgli, fire has been central to human identity and aspiration. Man’s control of fire distinguishes him from the rest of creation. Thus, in the Kipling story, the man-child Mowgli discovers that he can keep the tiger, Shere Khan, at bay with a burning brand. In Disney’s adaptation of Kipling’s The Jungle Book, King Louie and his troop of monkeys kidnap Mowgli in hopes of wresting from him the secret of fire and, thus, dominion. As Leon R. Kass notes in his book The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, while discussing the firing of bricks by the tower builders of Babel,

Fire is universally the symbol of the arts and crafts, of technology. Through the controlled use of fire’s transforming power, human beings set about to alter the world, presumably because, as it is, it is insufficient for human need. Imitating God’s creation of man out of the dust of the ground, the human race begins its own project of creation by firing and transforming portions of the earth.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was an author much interested in the elements and their symbolic meaning, wrote three tales that make explicit reference to fire in their titles: “Fire Worship,” “Earth’s Holocaust,” and “Ethan Brand.” Read in sequence they form an argument of sorts about technology, progress, and modernity — an argument that issues in a warning about man’s quest for dominion.

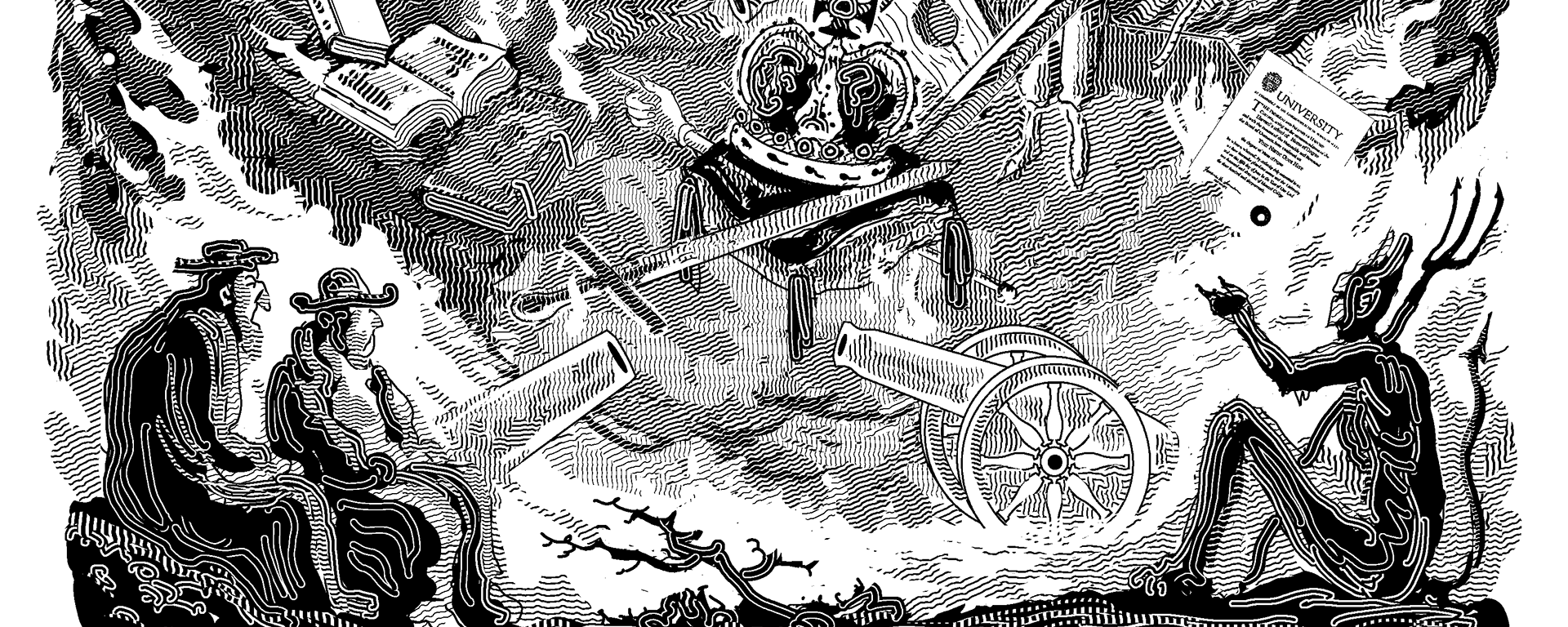

In the first of Hawthorne’s fire fables, “Fire Worship,” he traces and laments “a great revolution in social and domestic life” brought about by the “exchange of the open fireplace for the cheerless and ungenial stove.” “Fire Worship” is not so much a story as an essay of social criticism, not unlike an article that might appear in the pages of this journal observing the effects of some new device or application (like cell phones or the Internet) on the character and quality of human connection. There are today a fair number of people who are either leery of certain technologies (perhaps declining to own a television or regulating their children’s exposure to various electronic media) or at least prepared to acknowledge the downsides (such as the explosion in access to pornography via the Internet). However, we tend to take our furnaces and central heating for granted. Aware of fuel costs, we are no longer aware of any moral or spiritual costs. “Fire Worship” is a wonderful time-traveling exercise offering insights as startling as Socrates’ complaint in the Phaedrus about the perils of the written word. While we are no more likely to return to open hearths than to an oral culture, we can benefit from the remembrance, as Hawthorne indicates by the title of the collection in which “Fire Worship” appeared: Mosses from an Old Manse.

Of the twenty-six tales, essays, and sketches in the volume, two of them, “Fire Worship” and “Buds and Bird Voices,” are explicitly linked to the autobiographical title piece, “The Old Manse: The Author Makes the Reader Acquainted with His Abode.” That abode was a “mossgrown country parsonage” (the ancestral home of the priestly Emerson family), where, for three and a half years, the newly-married Hawthorne lived as the first “lay occupant.” “The Old Manse” is a transcendentalist idyll about the house (especially the study — “It was here that Emerson wrote ‘Nature’” — and superannuated library) and its natural environs (“the river, the battle field, the orchard, and the garden”). Similar in tone, although without the focus on scholarly productions, “Buds and Bird Voices” is a paean to the arrival of Spring. By contrast, “Fire Worship” is an anti-idyll — a wintry meditation on an advancing technological “abomination.” The seasonal setting of each piece is distinct: “Buds and Bird Voices” belongs to “balmy spring”; “The Old Manse” is set in summer and fall; “Fire Worship” opens in bleakest winter. Both the non-winter essays, however, make brief but pointed reference to the infernal contraption.

Why is the airtight stove an “enormity”? Hawthorne grants that the stove is vastly more efficient than the open hearth, consuming fewer cords of wood, generating more heat, with less risk of danger. Indeed, efficiency, comfort, and safety were the motives behind Benjamin Franklin’s invention of the cast-iron stove in the 1740s. Whereas Franklin fully subscribed to the Baconian and Cartesian faith in technology, Hawthorne is a dissenter. He challenges all three motives. Another name for the virtue of efficiency is the vice of inhospitality: “grudging the food that kept him cheery and mercurial, we have thrust him into an iron prison, and compel him to smoulder away his life on a daily pittance.” The comfort we gain from our stinginess is a “black and cheerless comfort.” We are deprived of “the bright face of [an] ancient friend, who was wont to dance upon the hearth and play the part of more familiar sunshine.” Even our increased safety is quite overrated, according to Hawthorne:

Nor did it lessen the charm of his soft, familiar courtesy and helpfulness, that the mighty spirit, were opportunity offered him, would run riot through the peaceful house, wrap its inmates in his terrible embrace, and leave nothing of them save their whitened bones. This possibility of mad destruction only made his domestic kindness the more … touching.

The gravamen of Hawthorne’s complaint, which is a complaint not just about the Franklin stove but about the spirit of Franklin, is that “the inventions of mankind are fast blotting the picturesque, the poetic, and the beautiful out of human life.” The stove is a representative instance, but also a special one, since fire is “that quick and subtle spirit, whom Prometheus lured from Heaven to civilize mankind.” Fire is both an elemental force of “wild Nature” — “he that comes roaring out of Ætna and rushes madly up the sky like a fiend breaking loose from torment” — and our instrument — “he is the great artisan and laborer by whose aid men are enabled to build a world within a world, or, at least, to smoothe down the rough creation which Nature flung to us.” But beyond his “terrible might” and “many-sided utility,” he was heretofore also our “homely friend.” Hawthorne calls fire “the great conservative of Nature” because of his part in all “lifelong and age-coeval associations.” The hearth is the center of the home, and the home is the foundation of larger enterprises. Hawthorne asserts that “While a man was true to the fireside, so long would he be true to country and law, to the God whom his fathers worshipped, to the wife of his youth, and to all things else which instinct or religion have taught us to consider sacred.” The virtues of marital fidelity, patriotism, and piety all take their spark from the domesticated fire.

Hawthorne attaches particular importance to the glowing face of the fire which works sympathetically upon the imagination. For whoever looks into the fire-light, “He pictured forth their very thoughts. To the youthful he showed the scenes of the adventurous life before them; to the aged the shadows of departed love and hope; and, if all earthly things had grown distasteful, he could gladden the fireside muser with golden glimpses of a better world” — all the while, “causing the teakettle to boil.” The stove, of course, retains (and even intensifies) the useful heat. However, it removes our contact with the light. The fire becomes invisible, damaging both communion and contemplation. In the opening sentence, Hawthorne speaks of a revolution not only in “social and domestic life,” but also “in the life of a secluded student.” Without “that peculiar medium of vision,” both fellowship and scholarship will take on a different — less insightful and generous — quality.

“Fire Worship” is a tightly constructed piece, just eleven paragraphs in length. After the opening four paragraphs, in which Hawthorne delineates the multifarious nature of fire, the central three paragraphs offer a description of a day around the hearth of “the good old clergyman, my predecessor in this mansion.” Hawthorne imagines him in his prime, decades before he would brick over the fireplace and install the wretched modern convenience. We see him writing a sermon under the influence of “the aspect of the morning fireside”; receiving a parishioner who has “been looking the inclement weather in the face” but to whom the “warmth of benevolence” is now extended. We see him, after making his own daily pastoral rounds, return to the twilight fireside, “a beacon light of humanity.” Finally, in the evening, the family gathers, “children tumbled themselves upon the hearth rug, and grave puss sat with her back to the fire.” After this commemorative portrait, Hawthorne declares: “Heaven forgive the old clergyman!” He notes the reasons that might have led the octogenarian to “bid farewell to the face of his old friend forever”: cutbacks in his monthly allotment of wood and the increasing draftiness of the old house; “but still it was one of the saddest tokens of the decline and fall of open fireplaces that the gray patriarch should have deigned to warm himself at an airtight stove.”

The final four paragraphs shift to Hawthorne, who, despite his views on the matter, compounded the “shame” by installing three more stoves throughout the house, so now “not a glimpse of this mighty and kindly one will greet your eyes.” Hawthorne finds himself in the position of so many technological doubters. His conscience worries and objects, but in point of fact, he allows himself to follow the current. Hawthorne’s own complicity may help explain his ironic tone. In the preface to the Mosses, he says that these sketches are “often but half in earnest.” So while he has no intention of forwarding a rejectionist policy of radical reaction, he does want us to reflect on the moral effects of living with stoves and furnaces. Poetic hyperbole is part of his method. He writes from experience — the experience of his own grudging participation. As a member of the transitional generation, he warns of the coming hearthlessness.

As he had described the gladsome character of fire’s visible presence, Hawthorne in turn describes the malign character of its invisible presence. Though caged, the fire can still be felt in scorched fingers and singed garments; and smelled in the “volumes of smoke and noisome gas” that issue through the cracks; and especially heard — sighing, hissing, and moaning, “burdened with unutterable grief” at “the ingratitude of mankind … to whom he taught all their arts, even that of making his own prison house.” In transforming the transformative agent, we live with a “darkened source.”

Hawthorne traces the “invaluable moral influences” that will be lost when “the sacred trust of the household fire … transmitted in unbroken succession from the earliest ages” has been extinguished by “physical science.” The effects will be most profound for future generations. Those who grew up around the fireside will retain certain salutary habits:

We shall draw our chairs together as we and our forefathers have been wont for thousands of years back, and sit around some blank and empty corner of the room, babbling with unreal cheerfulness of topics suitable to the homely fireside. A warmth from the past — from the ashes of by-gone years and the raked-up embers of long ago — will sometimes thaw the ice about our hearts.

For the young, however, raised with either “the sullen stove” or, even worse, “furnace heat” in “houses which might be fancied to have their foundation over the infernal pit,” the mutual bond will be broken. Hawthorne predicts that “There will be nothing to attract these poor children to one centre…. Domestic life, if it may still be termed domestic, will seek its separate corners.” If Hawthorne is right, it didn’t require televisions and personal computers in every room for the family to be atomized. What we call “central heat” is in truth diffused heat. With heat diffused so efficiently into every nook and cranny, there is no necessity for family and friends to gather together, and no special atmosphere (which “melts all humanity into one cordial heart of hearts”) to vivify the occasional grouping. Along with the heat, fellow-feeling is diffused. Social intercourse of many types will suffer or even disappear: “easy gossip; the merry yet unambitious jest; the lifelike, practical discussion of real matters in a casual way; the soul of truth which is so often incarnated in a simple fireside word.” Instead, “conversation will contract the air of debate.”

As a kind of confirmation of Hawthorne’s intuition, it is interesting that for a long time after the advent of whole-house heating, homes continued to be built with at least one functioning fireplace, usually in the living room. However, beginning in the 1960s and 70s, new homes were constructed without even that token of tradition. In the last two decades, this trend toward hearthlessness has been dramatically reversed. New homes now have multiple fireplaces, in kitchens, family rooms, and master bedrooms. They are of course often gas or electric, so they are convenient, but they do offer a visible flame (or simulacrum thereof). Wood-burning fire-pits for the deck are also all the rage. Sales of candles increase every year. Perhaps there is an ineradicable human longing for the fireside and fire-light. We seek ways to compensate for the social and psychic disruptions of technological progress. It remains an open question whether these modern versions of the hearth (which are strictly speaking gratuitous) can truly preserve traditional practices and virtues.

In the final paragraph, Hawthorne returns to his opening claim about the linkage between the virtues of the domestic, religious, and political realms. His text is the ancient “exhortation to fight ‘pro aris et focis,’ for the altars and the hearths.” These are the sacred locations — kindred in spirit — that inspire patriotic sacrifice. Hawthorne calls the hearth “a divine idea, imbodied in brick and mortar,” presided over by mothers rather than priests. The hearth with its chimney, though constructed of the same brick that built the impious tower of Babel, expresses a very different aspiration. Those who would defile the hearth would stop at nothing:

The man who did not put off his shoes upon this holy ground would have deemed it pastime to trample upon the altar. It has been our task to uproot the hearth. What further reform is left for our children to achieve, unless they overthrow the altar too?

Once hearth and altar are both gone, Hawthorne wonders what patriotism will rest upon or appeal to. “Fight for your stoves!” is not a battle cry that will “rouse up native valor.”

One change begets others. At the close of “The Old Manse,” Hawthorne tells of his forced relocation from the Old Manse to the Custom-House prompted by the current owner’s desire to renovate — not a project of which Hawthorne approves, inasmuch as “the hand that renovates is always more sacrilegious than that which destroys.” The renovating, progressive temperament is the main theme of Hawthorne’s second fire story, “Earth’s Holocaust.”

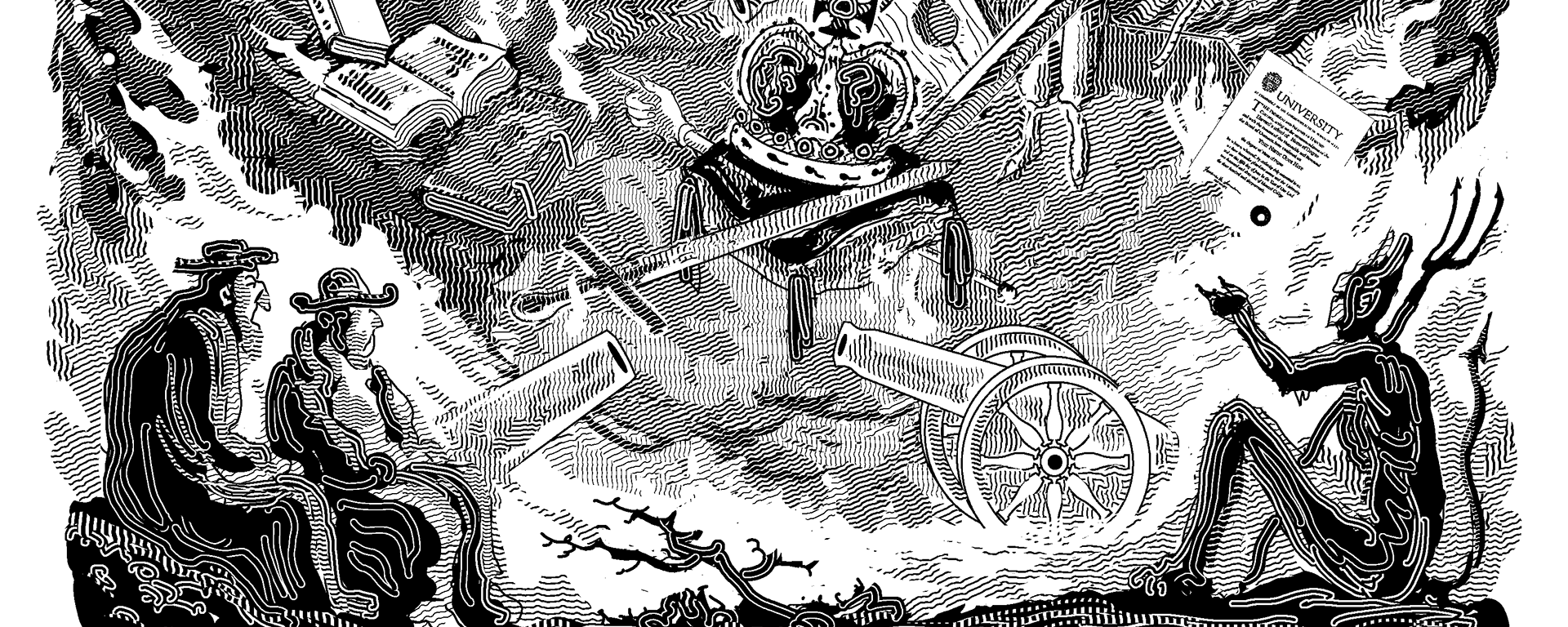

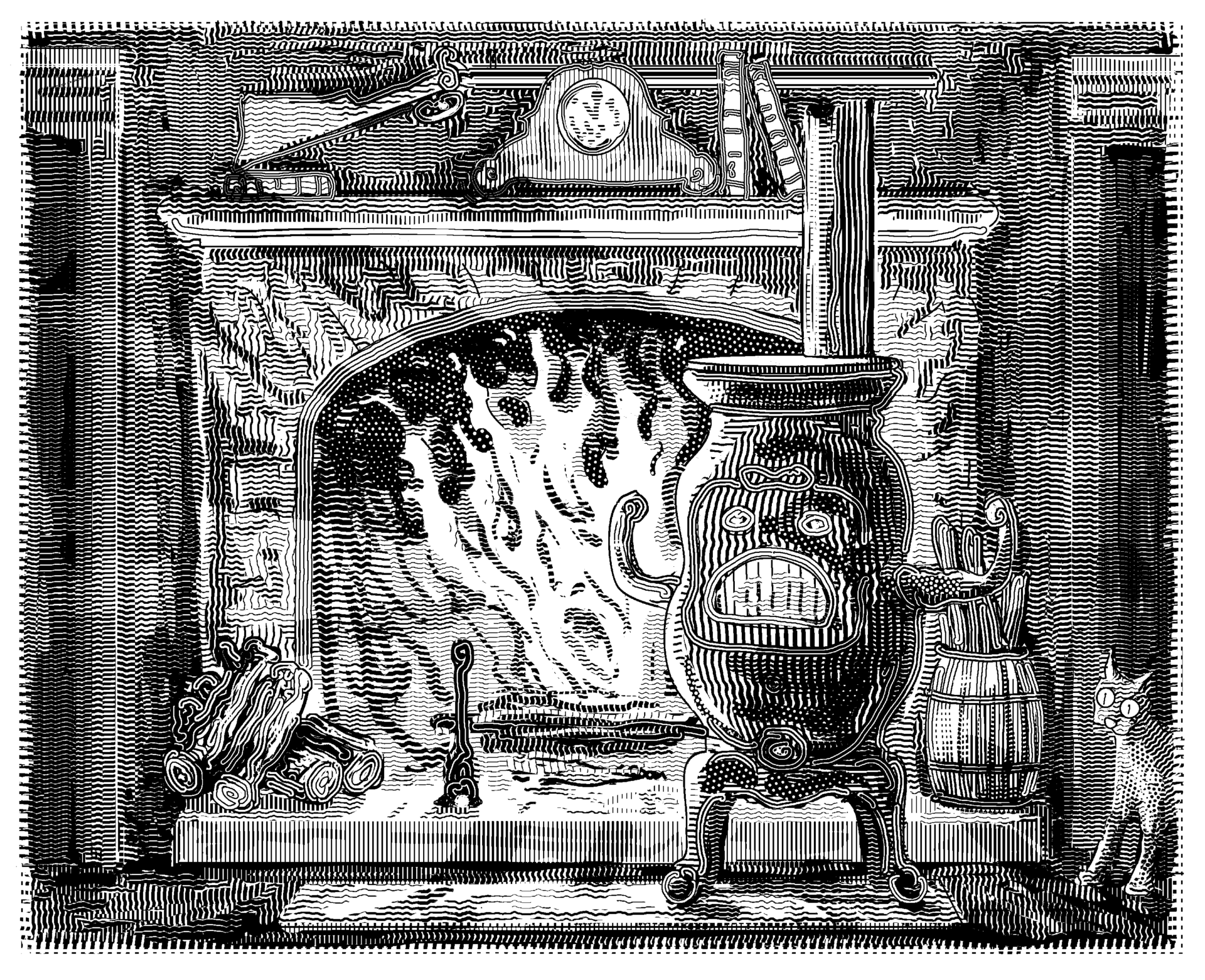

In this satirical allegory we find not a hearth but a bonfire, by means of which Earth’s inhabitants plan to rid themselves of “an accumulation of wornout trumpery.” Instead of being “the great conservative,” fire will become the cleansing and purging agent of reform. The site of the bonfire, selected by “the insurance companies” with a view to safety and accessibility, “was one of the broadest prairies of the west.” The account of the fire’s progress and the reactions of various bystanders are given by a narrator who hopes that “the illumination of the bonfire might reveal some profundity of moral truth.”

After the bonfire is kindled with “yesterday’s newspapers,” a group of “rough-looking men” hurl all the paraphernalia of aristocracy into the fire, such things as “the blazonry of coat armor, the crests and devices of illustrious families, pedigrees that extended back … into the mist of the dark ages,” at the sight of which “the multitude of plebeian spectators set up a joyous shout.” The narrator’s comment acknowledges the justice of the democratic triumph over the past. After all, the nobility were “creatures of the same clay and same spiritual infirmities, who had dared to assume the privileges due only to Heaven’s better workmanship.” Nonetheless, Hawthorne does not allow the reader to forget the beauty that is lost with the demise of aristocracy. A “grayhaired man, of stately presence,” steps forward and lectures the spectators:

People, what have you done? This fire is consuming all that marked your advance from barbarism, or that could have prevented your relapse thither. We, the men of the privileged orders, were those who kept alive from age to age the old chivalrous spirit; the gentle and generous thought; the higher, the purer, the more refined and delicate life. With the nobles, too, you cast off the poet, the painter, the sculptor — all the beautiful arts; for we were their patrons, and created the atmosphere in which they flourish. In abolishing the majestic distinctions of rank, society loses not only its grace, but its steadfastness.

“A rude figure,” who threatens to cast the nobleman himself into the fire, responds with a speech in defense of various natural superiorities (“strength of arm … wit, wisdom, courage, force of character”) but dismissive of the “nonsense” of inherited “place and consideration.” The final word on this first reform goes to a “grave observer,” with whom the narrator converses, who approves of the burning of this “antiquated trash” but with a caveat: “if no worse nonsense comes in its place.”

Next upon the pile went all the insignia and pomp of monarchy. The age of “universal manhood” having arrived, no one speaks up for monarchy. The “fallen nobleman,” hooted from the scene for defending his prerogatives, has “shrunk back into the crowd.” Hawthorne seems to suggest that the fundamental political alternatives are aristocracy and democracy. Monarchy is simply a further refinement of an order built upon hereditary rank. As Montesquieu argued: “the nobility is of the essence of monarchy.” Once the notion of rank is discredited, monarchy cannot sustain itself. To escape the smoke and smell of the burning purple wardrobes, the narrator and his acquaintance move to the other side of the bonfire, where another facet of “the general and systematic measures of reform” is underway.

The “votaries of temperance” have collected “the whole world’s stock of spirituous liquors” and offered them to the “insatiable thirst of the fire fiend.” Once again, “the multitude gave a shout as if the broad earth were exulting in its deliverance from the curse of ages.” However, “the joy was not universal.” In fact, there were “many” who “deemed that human life would be gloomier than ever.” The “last toper” steps forth as their spokesman:

What is this world good for … now that we can never be jolly any more? What is to comfort the poor man in sorrow and perplexity? How is he to keep his heart warm against the cold winds of this cheerless earth? And what do you propose to give him in exchange for the solace that you take away? How are old friends to sit together by the fireside without a cheerful glass between them? A plague upon your reformation! It is a sad world, a cold world, a selfish world, a low world, not worth an honest fellow’s living in, now that good fellowship is gone forever!

Despite the “great mirth” of the bystanders at this harangue, the narrator “could not help commiserating the forlorn condition of the last toper” who had indeed lost his “boon companions.” He had also managed to “filch a bottle of fourth-proof brandy that fell beside the bonfire” — the first concrete act of resistance. The reformers don’t notice, however. In their moralistic “zeal,” they are casting tea, coffee, and tobacco “upon the heap of inutility.” The assault on tobacco, in particular, startles and provokes “an old gentleman” who declares: “Every thing rich and racy — all the spice of life — is to be condemned as useless. Now that they have kindled the bonfire, if these nonsensical reformers would fling themselves into it, all would be well enough!” Earlier, the fallen nobleman was told to count himself lucky to have lost his pedigree rather than his life to the fire. Now, the reformers themselves are at least passively wished into the pyre. The final word, however, goes to “a stanch conservative” who seems to warn against such wishes. With grim irony, he predicts the course of the holocaust’s relentless logic: “Be patient … it will come to that in the end. They will first fling us in, and finally themselves.”

The narrator’s attention shifts again, “from the general and systematic measures of reform” to “the individual contributions.” There is a purely personal animus toward the past. The jilted and the bored toss their love letters, disappointed professionals throw in the tools of their trade (including the false teeth of “a hack politician” defeated for office), and, most striking to the narrator, “a number of ladies, highly respectable in appearance,” propose “to fling their gowns and petticoats into the flames, and assume the garb, together with the manners, duties, offices, and responsibilities, of the opposite sex.” As the feminist slogan of the 1960s expressed it: “the personal is political.” Before the narrator can witness the outcome of this moment in which female dissatisfaction is annealed into feminism, a “poor, deceived, and half-delirious girl” attempts to throw herself into the fire and is rescued by “a good man” who counsels “patience.” He attempts to instruct her in the difference between what is fit for the fire — “things of matter and creations of human fantasy” — and what is not — “a living soul” meant for “eternity.” Insisting, however, that “the sunshine is blotted out,” she only sinks from “frenzy” to “deep despondency.” While it is possible that a particular reform has driven her mad (say, the one contemplated by the respectable ladies), it seems more likely from the textual evidence that she embraces the fire as a final solution to some earlier trauma (thus, she had rushed toward it, “exclaiming that she was the most worthless thing alive or dead”). Her attempted suicide demonstrates the difficulty of setting any bounds to the fire’s destructive use. Regret can extend well beyond yesterday’s feelings and actions, well beyond the conventions and choices of the past, to one’s very essence and existence. The flame of modernity attracts and consumes the flighty moth of “the self.”

The scene shifts dramatically back to politics proper, both foreign and domestic, with the next two reforms targeting the weapons of war and the instruments of capital punishment. Disarmament, the prelude to the abolition of war itself, occasions “great diversity of opinion,” with “the hopeful philanthropist” greeting the millennium, while those “in whose view mankind was a breed of bulldogs, prophesied that all the old stoutness, fervor, nobleness, generosity, and magnanimity of the race would disappear.” Despite the doubters, the reform proceeds apace: “It was wonderful to behold how these terrible instruments of slaughter melted away like playthings of wax.” Commentary, in this case, is provided by a “veteran commander” and a man identified only by his “sneer.” The commander believes that “all this foolery has only made more work for the armorers and cannon founders.” Since “the battle field is the only court” where suits between nations can be tried, the “necessity of war” will return. The narrator speaks up on behalf of universal peace, suggesting that a transnational tribunal of “Reason and Philanthropy” will be constituted. In effect, there will be a new sovereign; international law will replace national sovereignty. In the midst of the discussion between the commander and the narrator, the man with the sneer interjects a comment that reaches deeper than the debate over whether rearmament will occur: “When Cain wished to slay his brother, he was at no loss for a weapon.” The problem is man’s heart, not his arms.

While God dealt with Cain in his own way, the descendants of Cain — Cain, remember, was the founder of the first city and the forefather of Noah — have instituted their own method: capital punishment. The reformers, after bringing the whole world under juridical control, seek to make human judgment milder. In casting “those horrible monsters of mechanism” — the headsmen’s axes and halters, the guillotine and gallows — into the blaze, they correct “the long and deadly error of human law.” Not surprisingly, the executioner, “an ill-looking fellow,” defends his livelihood “with brute fury.” However, the narrator notes that men consecrated to the benevolent guardianship of society also took “the hangman’s view of the question.” One of this class declares:

You are misled by a false philanthropy; you know not what you do. The gallows is a Heaven-ordained instrument. Bear it back, then, reverently, and set it up in its old place, else the world will fall to speedy ruin and desolation!

The reformers prevail when one of their leaders counters: “How can human law inculcate benevolence and love while it persists in setting up the gallows as its chief symbol?” In a pattern that has become familiar, this “triumph of the earth’s redemption” is hedged about with doubts. Although the narrator declares the act “well done,” the “thoughtful observer” is more cautious: “well done, if the world be good enough for the measure. Death, however, is an idea that cannot easily be dispensed with in any condition between the primal innocence and that other purity and perfection which perchance we are destined to attain.” Still, he thinks “the experiment” is worth trying.

The next rash of moral reforms serves as a verdict of sorts on the experiment. With the most fearsome bulwark of society gone, the crowd is caught up in more radical measures: burning marriage certificates, currency, title deeds, statute books, and written constitutions. The narrator himself finally balks at this assault on the institutions of marriage, private property, and government. The growth of radicalism can be seen by comparing the first phase of “individual contributions” to the bonfire to this second phase. Earlier, disappointed lovers rejected the past, burning old “bundles of perfumed letters and enamoured sonnets.” Now, in burning “their marriage certificates” and other instruments of fixed commitments, they are in some sense burning the future, or at least the link between present and future. Each of these institutions depends on a present promise (or agreement or contract) that binds and determines the shape of the future. Such promises, however voluntary, can be experienced as a restriction on freedom. Accordingly, the very notions of promise-keeping and law-abidingness must be abolished, so that each moment will be left radically undetermined. The “good people around the bonfire” are pursuing a powerfully antinomian version of autonomy. For the self to be absolutely sovereign, it must be above all law, even those laws that it gives to itself. The arbitrary self scorns the rigors of self-government.

Interestingly, the reformers expect not only the fullest freedom but the widest fellowship as well. Free love will yield “a higher, holier, and more comprehensive union”; once property claims are destroyed, “the whole soil of the earth [will] revert to the public.” Belonging will be universal rather than exclusive or specific. In a “consummated world,” freedom and fraternity will be conjoined. Departing from his usual practice, Hawthorne does not provide any expressions of doubt or debate on these reforms, other than the narrator’s opening remark that “I was hardly prepared to keep them company.” Perhaps he assumes that most readers — even relatively naïve ones like the narrator — will part company with the enthusiasts at this point.

The narrator’s attention is now drawn to matters that “concerned my sympathies more nearly.” The book burning has begun. “The world’s entire mass of printed paper, bound or in sheets” is to be consigned to the fire. It is not just written law that oppresses, but the written word of all types. “A modern philosopher” heartily approves, since we need to “get rid of the weight of dead men’s thought.” There follows a delightful excursus upon literature, as the narrator is able to judge the quality of each author’s (or nation’s or genre’s) writing by how it burns. Some authors generate “a brilliant shower of sparkles” (Voltaire, for instance); others “smouldered away to ashes like rotten wood” (the class of commentators); the Germans emit “a scent of brimstone”; while “the English standard authors made excellent fuel, generally exhibiting the properties of sound oak logs.” Special mention is made of Milton (“a powerful blaze”) and Shakespeare, from whom

there gushed a flame of such marvellous splendor that men shaded their eyes as against the sun’s meridian glory; nor even when the works of his own elucidators were flung upon him did he cease to flash forth a dazzling radiance from beneath the ponderous heap. It is my belief that he is still blazing as fervidly as ever.

The burning of Shakespeare occasions a debate between the narrator and “a critic” — doubtless a follower of Emerson — about poetic originality and the anxiety of influence. The critic favors self-reliance, whereas the narrator argues for standing on the shoulders of ancient giants: “It is not every one that can steal the fire from heaven like Prometheus; but when once he had done the deed, a thousand hearths were kindled by it.” Appropriately, the narrator goes on to praise humble works like “Mother Goose’s Melodies,” “the single sheet of an old ballad,” and “an unregarded ditty of some nameless bard,” which he observes burn brighter and longer than many more acclaimed works. As in “Fire Worship,” Hawthorne links the poetic and the prosaic; the Promethean genius Shakespeare lights the way for more homely, domesticated writers. This fire of imagination, whether heavenly or hearthly, is profoundly different from the bonfire of progress.

In “Fire Worship,” Hawthorne spoke of the fiendish, riotous form of fire “to whose ravenous maw, it is said, the universe shall one day be given as a final feast.” Here the narrator fears that the apocalypse may be the next item on the reform agenda: “Unless we set fire to the earth itself, and then leap boldly off into infinite space, I know not that we can carry reform to any farther point.” His friend, however, realizes there is still fuel to come “that will startle many persons who have lent a willing hand thus far.” The fresh fuel turns out to be the accoutrements of religion: surplices, mitres, crosses, baptismal fonts, everything from the “undecorated pulpits” of New England to the “spoils” of St. Peter’s. Despite the narrator’s initial “astonishment,” he reconciles himself to this latest reformation with the thought that the purging of external emblems may render faith “more sublime in its simplicity” and that “the woodpaths shall be the aisles of our cathedral — the firmament itself shall be its ceiling.”

The reform, however, is not complete. There is a final consummation. The Bible, which we learn had been spared during the “general destruction of books,” is now sacrificed by “the Titan of innovation.” Reform is its own religion. Hawthorne describes the apotheosis:

But the Titan of innovation, — angel or fiend, double in his nature, and capable of deeds befitting both characters, — at first shaking down only the old and rotten shapes of things, had now, as it appeared, laid his terrible hand upon the main pillars which supported the whole edifice of our moral and spiritual state. The inhabitants of the earth had grown too enlightened to define their faith within a form of words or to limit the spiritual by any analogy to our material existence. Truths which the heavens trembled at were now but a fable of the world’s infancy. Therefore, as the final sacrifice of human error, what else remained to be thrown upon the embers of that awful pile except the book which, though a celestial revelation to past ages, was but a voice from a lower sphere as regarded the present race of man? It was done!

The Church Bible, family Bible, and bosom Bible are all flung in. As in “Fire Worship,” the institutional structures of society are linked. Tearing down one prepares the way for the demolition of others. The titanic spirit of reform, which is hostile to tradition qua tradition, is incapable of making distinctions between unsound and sound, between the superannuated and the timeless.

In his easygoing way, the narrator has adjusted to most of the reforms, arguing for instance that the general book-burning would open “an enviable field for the authors of the next generation” and counseling “the desperate bookworm” to consider whether “Nature” is not “better than a book.” At the Bible-burning, however, he grows pale. Somewhat surprisingly, his distress — and the distress of the other onlookers — is not shared by the man who has been at his side throughout. With “singular calmness,” the unnamed man assures him that “there is far less both of good and evil in the effect of this bonfire than the world might be willing to believe.” The culture-warriors on both sides of the reform question are apparently mistaken. Perplexed, the narrator wonders how the world will continue with “every human or divine appendage of our mortal state” gone. His “grave friend” claims that in the morning “you will find among the ashes every thing really valuable…. Not a truth is destroyed nor buried so deep among the ashes but it will be raked up at last” — a proof of which is already visible in the pages of Holy Scripture, which had not “blackened into tinder” but instead “assumed a more dazzling whiteness.” The narrator leaps to the happy conclusion that the fire purifies. If so — “if only what is evil can feel the action of the fire” — then the fire must have been “of inestimable utility.” The philosophic observer, however, directs him to “listen to the talk of these worthies” — a distinctive group gathered in front of the pile — to learn “something useful.” The “profundity of moral truth” that the narrator had sought in the fire’s illumination is to be found instead in the conversation of a party formed by the hangman, the last thief, the last murderer, and the last toper.

They are despondent, passing the filched bottle of spirits. The hangman offers to dispatch them all, including himself, from the nearest tree (no fiery death for them). A new figure joins them: “a dark-complexioned personage” whose eyes “glowed with a redder light than that of the bonfire.” He confidently informs them that they “shall see good days yet” since the conflagration begun by “these wiseacres” amounts to “just nothing at all.” This figure, whom the narrator dubs “the evil principle,” has spent the entire evening laughing at the reform project, since it overlooked “the human heart” — “that foul cavern” from which “will reissue all the shapes of wrong and misery…. O, take my word for it, it will be the old world yet!”

The narrator has been helped to the thought — “how sad a truth” — that “man’s agelong endeavor for perfection” is fundamentally misguided, since it is a project of “the intellect” that doesn’t reach “the heart … the little yet boundless sphere wherein existed the original wrong.” Hawthorne does not suggest how (or whether) one could “purify the inward sphere.” Certainly, the strategy of “Earth’s Holocaust” applied to human beings themselves — tried in the last century by the most zealous of purging reformers, both fascist and communist — does not work. Hawthorne’s teaching is anti-millenarian and anti-utopian. There is a hint that the revealed word — or even a human “pen of inspiration” like Shakespeare’s — can touch the Heart. But politics can never be reformative in the deep sense. With sadness rather than glee, Hawthorne joins the Devil in his dismissal of ideological agendas. Political expectations need to be moderated. Hawthorne is not a movement conservative any more than he is a movement liberal. His message, however, circles back around to defend the traditional institutions of the social order (family and property, even war and capital punishment). He defends them not as fine accomplishments, but rather as somewhat unfortunate necessities, themselves involving cruelty, hypocrisy, and corruption. Yet, they serve as restraints upon the worst of us and the worst in each of us.

Earth’s Holocaust” closes with the devil’s laughter; “Ethan Brand” opens with a disconcerting “roar of laughter” and closes with a “fearful peal of laughter” from another fiendish figure. The last of Hawthorne’s fire tales is an inquiry into the perversion of the Intellect in a man who starts with “love and sympathy for mankind” but finishes “a cold observer, looking on mankind as the subject of his experiment.” The prediction of the “stanch conservative” in “Earth’s Holocaust” — that those who fed the bonfire would ultimately fling themselves into it — comes to pass in “Ethan Brand.”

The setting for the story — which with a protagonist, a plot, and third-person narration is more of a story than either “Fire Worship” or “Earth’s Holocaust” — is a lime-kiln, a special kind of furnace. There, Brand conceives his unique quest for the Unpardonable Sin — some human act that will, Brand believes, extend “man’s possible guilt beyond the scope of Heaven’s else infinite mercy.” There, too, after an eighteen-year pursuit, Brand returns, having discovered within himself what he sought, intent on completing his mission by suicide.

We are told that tending a lime-kiln is a lonesome occupation and, for those few so inclined, like Ethan Brand, “an intensely thoughtful” one. From “Fire Worship” we know the sympathetic power of fire to reflect the inner man. In Brand’s case that communion produced “the Idea.” His already “dark thoughts” were “melted” into “the one thought that took possession of his life”: a quest for the Unpardonable Sin. The kiln, of course, has nothing of the forgiving quality of a hearth-fire. Indeed, Hawthorne, with reference to Pilgrim’s Progress, compares the kiln to “the private entrance to the infernal regions, which the shepherds of the Delectable Mountains were accustomed to show to pilgrims.” When Bartram — the ordinary, unthinking man who now serves as lime-burner — keeps watch upon the fire, he does so “turning his face from the insufferable glare.” Brand, however, immediately upon returning from his impious pilgrimage, “fixed his eyes — which were very bright — intently upon the brightness of the furnace, as if he beheld, or expected to behold, some object worthy of note within it.” Later in the story, he “bent forward to gaze into the hollow prison-house of the fire, regardless of the fierce glow.” Later still, he “sat looking into the fire, as if he fancied pictures among the coals.” Just as Brand is transfixed by the “lurid blaze,” so little Joe — the sensitive son of the insensitive Bartram — is transfixed by Brand’s face, which mirrors the kiln. (Brand’s eyes “gleamed like fires within the entrance of a mysterious cavern.”) Wisely, the child begs his father to shut the furnace door to break the spell.

Even the “dull and torpid” Bartram, unconsciously reminded of his own sins, begins to sense the horror of Brand’s “Master Sin.” Bartram’s fears take a conventionally supernatural shape, as he remembers the stories told about Ethan Brand: how he “conversed with Satan himself” and summoned a fiend from the furnace “to share in the dreadful task” of finding the sin that surpasses God’s understanding. What Bartram fails to understand is that Brand now regards himself as beyond good and evil. Thus, Brand rebukes him, saying: “what need have I of the devil? I have left him behind me, on my track. It is with such half-way sinners as you that he busies himself.” Whereas Bartram had been frightened by a heartfelt kinship based on universal human sinfulness, Brand denies the connection. On his reckoning, his sin is not of the same “family.” Asked by Bartram what “the Unpardonable Sin” is, he answers: “The sin of an intellect that triumphed over the sense of brotherhood with man and reverence for God, and sacrificed everything to its own mighty claims!” Brand speaks “with the pride that distinguishes all enthusiasts of his stamp” — a textual indication that Brand’s sin is perhaps not as special as he believes. His pride may indeed be the “Master Sin” (or the original sin), without being the “Unpardonable Sin.”

Nonetheless, there is a sense in which Brand’s sin, especially his self-murder, is unpardonable. One suspects that, for Brand, self-murder was a feasible substitute for the murder of all mankind. His interactions with the townspeople who assemble on the forlorn hillside on the news of his return indicate as much. Calling them “brute beasts,” he commands them to “Get ye gone!” To the “Jew of Nuremberg” — the traveling showman who tellingly mocks the nihilism of Brand’s quest — his instruction is more explicit: “get thee into the furnace yonder!” Through suicide, Brand murders the world he despises, along with the self. Moreover, suicide is a form of murder by which he willfully removes himself from the realm of remorse and redemption. Perhaps because it was understood as a declaration of the most profound and radical alienation, suicide was long punished under the civil law, and suicides were denied the solace of the church graveyard, populated with fellow sinners.

Not surprisingly, “Brand” is a name rich in religious significance. There are Old Testament references to Israel being “a brand plucked from the burning” (Zechariah 3:2 and Amos 4:11). In America, the phrase was made famous by Cotton Mather in his books about redeeming women from witchcraft, A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning and Another Brand Pluckt Out of the Burning, and then by John Wesley, who adopted the Biblical phrase as a description of his own deliverance from danger (he was rescued from an arsonist’s blaze as a child) and as a metaphor for spiritual salvation. Wesley requested the phrase “A brand plucked out of the burning” as his epitaph.

In Hawthorne’s version, there is no plucking out, no rescue, no redemption. The narrative convention is aborted or reversed; hence the subtitle of the story: “A Chapter from an Abortive Romance.” Hawthorne’s Brand, claiming to have fulfilled his impious quest for the “Unpardonable Sin,” triumphantly throws himself into the flames. His first name “Ethan” means “steadfast,” and he does indeed hold to his world-obliterating intention.

How did Ethan Brand arrive at this paroxysm of misanthropy? Hawthorne suggests a surprising genealogy, tracing the development of misanthropy out of philanthropy. We are told that Brand began with “love and sympathy for mankind,” and more especially with “pity for human guilt and woe.” Like the reformers of “Earth’s Holocaust,” he sought to free men from their burdens. In Brand’s case, it was human guilt in particular that he wanted to assuage or remove. The quest for the unpardonable sin was conceived as instrumental to that goal. While Hawthorne does not reveal the precise steps in Brand’s reasoning, we might speculate that Brand was led to the thought that men will be plagued by guilt so long as they believe in the need for divine pardon. If there were an unpardonable act, one might move beyond guilt, beyond good and evil, beyond God. What Hawthorne does tell us is that Brand’s quest (initially entered upon with reluctance) triggered a “vast intellectual development” that “disturbed the counterpoise between his mind and heart.” He becomes “a cold observer, looking on mankind as the subject of his experiment, and, at length, converting man and woman to be his puppets, and pulling the wires that moved them to such degrees of crime as were demanded for his study.” Whatever their crimes, they pale in comparison to Brand’s. It is he, the manipulator, who becomes “a fiend.”

In his ruthlessness and monomania, Ethan Brand is similar to Hawthorne’s other experimenters and men of science. Aylmer in “The Birth-mark” and Dr. Rappaccini in “Rappaccini’s Daughter” both put science before all else, conducting lethal experiments upon those dearest to them — a wife in one case, a daughter in the other. The only experiment of Brand’s about which we learn any details involved a girl whom Brand “had made the subject of a psychological experiment, and wasted, absorbed, and perhaps annihilated her soul, in the process.” In these men of science, even erotic and paternal love is subordinated to libido sciendi. As Hawthorne describes in the opening paragraph of “The Birth-mark,” such ardent intellects believe that their pursuit “would ascend from one step of powerful intelligence to another, until the philosopher should lay his hand on the secret of creative force and perhaps make new worlds for himself.” While “The Birth-mark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter” trace the course of the experiments and the disastrous effects on the research subjects, “Ethan Brand” offers a more interior look at the consequences of “faith in man’s ultimate control over Nature.” What does this ardency of intellect do to the scientist himself? As a result of the shift in perspective, one feels a compassion for Ethan Brand that one does not feel for Aylmer or Rappaccini. When Bartram and his son retire for the evening, leaving Brand to watch the fire, the boy “looked back at the wayfarer, and the tears came into his eyes, for his tender spirit had an intuition of the bleak and terrible loneliness in which this man had enveloped himself.”

The climax confirms the boy’s intuition. As the atheistic descendant of the Puritans, Brand embraces the hell-fire of the lime-kiln as the only element that will receive him. He no longer belongs to the human or natural order. The earth is no longer his “mother.” His “frame” will not return to ashes and dust within her bosom. He no longer shares brotherhood with the rest of mankind. The “stars of heaven” no longer draw him “onward and upward.” The next morning, when the lime-burner checks his kiln, fearing that five-hundred bushels of lime have been spoilt by Brand’s dereliction, he finds instead that “the marble was all burnt into perfect, snow-white lime,” and “on its surface … , — snow-white too, and thoroughly converted into lime, — lay a human skeleton” with “the shape of a human heart” visible “within the ribs.” Although perplexed that a man could have a marble heart, the practical Bartram judges that Brand’s heart was “burnt into what looks like special good lime” and that he is “half a bushel the richer for him.”

Hawthorne has chosen Brand’s ironic fate carefully. The furnace has processed Brand into lime, one of mankind’s oldest chemicals and a key ingredient in the manufacture of bricks. Brand has become the matter of technological production, rather than its master.

While fire has always been associated with the arts and sciences, it took on new significance at the start of the modern scientific revolution. Descartes, for instance, reflects on the nature of fire and its role in creation in his Discourse on Method. In the Biblical account, ashes are transmuted into Adam by means of “the breath of life”; in Descartes’ account, the breath of life is understood in purely mechanical terms as “heat” or energy. Thus, God “kindled in the man’s heart one of those fires without light which I had already explained and which I did not at all conceive to be of a nature other than what heats hay when it has been stored before it is dry, or which makes new wines boil when they are left to ferment after crushing.” According to Descartes, we have been cooked up like compost or fermented like a nice glass of bubbly — processes that would seem to be comprehendible and reproducible by man himself. There may be a slight problem with the analogies, however, since the damp hay is decomposing, as are the grapes. Can animal life really be understood on the model of heat-generating rot? This may explain why medicine is for Descartes (and modern science in general) the “indispensable” science; we must learn to regulate the heat within. According to Descartes, “the animal spirits” are “like a very pure and lively flame” and the body a kind of furnace whose pilot light could perhaps be re-engineered to be perpetual. Accordingly, Descartes demands a practical (or technological) rather than a speculative science, pursuing “the invention of an infinity of devices,” directed principally at human health and comfort.

Descartes’ famous method, which culminates in the project that Joseph Cropsey dubbed a “Mechanical Jerusalem,” was conceived, by Descartes’ own testimony, while he spent a winter day confined in a poêle or stove-heated room. It would not have surprised Nathaniel Hawthorne to learn that this audacious project to make men “the masters and possessors of nature” was concocted by a solitary man cooped up with only caged fire for company. Fire without light yields overheated plans that lose sight of human limitations and deeper human needs. Remember Hawthorne’s warning in “Fire Worship” about the distorted lucubrations of stove-warmed scholarship. It is but a short step from the modern scientific project to the various modern political projects, on display in “Earth’s Holocaust,” that abstract from the human heart in their inflamed rush to improve the human lot. In “Ethan Brand,” Hawthorne shows us the surprising terminus of this hypertrophy of the intellect (visible already in Descartes’ cogito ergo sum). The unmoored mind becomes radically alienated from human life. What emerged from the furnace is ultimately consumed by it. In his three fire tales, Hawthorne exposes the limitations of our modern votaries of science and technology. In “Fire Worship” he uncovers the human costs of technological advance, in “Earth’s Holocaust” he shows the fallacy of the utopian belief in universal enlightenment, and in “Ethan Brand” he reveals the nihilism of the autarchic intellect.

Before we become too glum, however, we should remember that “Ethan Brand” ends happily. Hawthorne provides a brief sketch of an alternative vision of man, nature, and providence in his description of a restored and refreshed world on the morning after Brand’s suicide:

[Bartram] issued from the hut, followed by little Joe, who kept fast hold of his father’s hand. The early sunshine was already pouring its gold upon the mountain-tops; and though the valleys were still in shadow, they smiled cheerfully in the promise of the bright day that was hastening onward. The village, completely shut in by hills, which swelled away gently about it, looked as if it had rested peacefully in the hollow of the great hand of Providence. Every dwelling was distinctly visible; the little spires of the two churches pointed upwards, and caught a fore-glimmering of brightness from the sun-gilt skies upon their gilded weather-cocks. The tavern was astir, and the figure of the old, smoke-dried stage-agent, cigar in mouth, was seen beneath the stoop. Old Graylock was glorified with a golden cloud upon his head. Scattered likewise over the breasts of the surrounding mountains, there were heaps of hoary mist, in fantastic shapes, some of them far down into the valley, others high up towards the summits, and still others, of the same family of mist or cloud, hovering in the gold radiance of the upper atmosphere. Stepping from one to another of the clouds that rested on the hills, and thence to the loftier brotherhood that sailed in air, it seemed almost as if a mortal man might thus ascend into the heavenly regions. Earth was so mingled with sky that it was a day-dream to look at it.

To supply that charm of the familiar and homely, which Nature so readily adopts into a scene like this, the stage-coach was rattling down the mountain-road, and the driver sounded his horn, while echo caught up the notes, and intertwined them into a rich and varied and elaborate harmony, of which the original performer could lay claim to little share. The great hills played a concert among themselves, each contributing a strain of airy sweetness.

Here, instead of a man-made tower (or Cartesian project) to assault the heavens, we have a natural stairway to heaven amid the clouds and hills. Ascent is accomplished by poetic imagination rather than construction or dominion. The human world with its institutions — family, village, churches (note the plural), and tavern (complete with smokers) — fits within an encompassing natural order. Post-Babel, the communities of men have indeed been scattered, but they are in communication with one another — hence, the stage-coach. Men are not without devices and appliances, but they work in concert with nature, establishing a “rich and varied and elaborate harmony.”