The Oregon Death with Dignity Act (ODDA), which permits physicians to write a prescription for lethal drugs to qualified terminally ill patients, has been in effect for a little over a decade. It has, from October 1997 to the present, been the only such statute in the United States permitting what is variously called “physician-assisted suicide,” “physician aid in dying,” or “death with dignity” (the statute refers to the procedure as the ending of life in a “humane and dignified manner”). However, in the November 2008 election, citizens in the state of Washington will have an opportunity to vote on ballot initiative I-1000, a measure that is essentially the same as the Oregon statute. The advocacy group promoting I-1000 has drawn on features of the Oregon experience to indicate that the Oregon law is “very safe and effective” and that “aid in dying is working.” To weigh the claims made by supporters and opponents of the proposed Washington state initiative, we ought to carefully examine the first decade of Oregon’s experience with physician-assisted suicide.

The Rationale for “Death with Dignity”

The central stated purpose of the ODDA — to expand patient control over end-of-life choices — has become its enduring ethical and cultural legacy. In Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health (1990), the U.S. Supreme Court asserted the legality of patient refusals of virtually every form of medical treatment, and in 1993, the Oregon legislature passed the Oregon Health Care Reform Act, which some fifteen years later remains a very expansive advance directives law. Still, even if it was not professionally, ethically, or culturally barred, it remained illegal to hasten death intentionally through the prescription of lethal drugs.

The ODDA aimed to end this ban on the grounds of patient self-determination and “choice.” The act’s advocates saw the conferral of a right to choose the manner and timing of one’s death as a logical extension of the expansive rights terminally ill patients possessed to refuse treatment. That is, they saw no principled difference between, on the one hand, refusing medical treatment in a way that would inevitably bring about death and, on the other, hastening death with a lethal drug. Once the outcome of death for a patient had already been accepted as a medically legitimate precedent in the context of patient refusals of treatment, then the question of the means to death should be settled not by the state, by medical professionals, or by religious institutions, but by the terminally ill patient.

While the principle of patient self-determination was a primary public justification for the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, the legislation’s advocates also appealed to a perception, supported by numerous publicized cases, of a painful dying experience for many terminally ill patients. That is, although the enacting statute itself frames the rationale for the act in terms of patient choice and autonomy (as is the case with Washington I-1000), a complementary argument — one with considerable public sway — was framed in terms of physician compassion and beneficence. This argument is somewhat at odds with the reality of patient experience. According to data compiled by the Oregon Department of Human Services from 1998 to 2007, the 341 patients who died under the provisions of the ODDA during that period cited a “loss of autonomy” more frequently than anything else as a concern contributing to their decision; 89 percent mentioned autonomy while only about 27 percent mentioned “inadequate pain control” (ranking it sixth among patient concerns). But in the public mind, the prospect of a painful dying experience looms large; it evokes a powerful visceral response from voters and caregivers.

A second argument for the Oregon Death with Dignity Act focused on the roles of participating physicians, seeking to provide physicians and other health care providers with immunity from prosecution. At stake in this rationale was professional autonomy — that is, the freedom of physicians to practice medicine according to their own standards of best practice in the care of the terminally ill — but also a shifting conception of professional integrity.

The longstanding professional objection to physician participation in euthanasia and to physician assistance in hastening death had been associated with an understanding that physician integrity entailed a commitment to healing and a prohibition of medical killing. However, supporters of the ODDA argued that the integrity of the medical profession was not entirely subsumed by a commitment to healing but should, at the very least, be complemented by a contractual model of physician respect for the choices of autonomous patients. Once professional integrity is not understood as commitment to an abstract ideal, such as healing, but to collaboration with patient self-determination, then the prospect of professional conflict is diminished. The act’s proponents also pointed to reports of extensive physician participation in hastening death outside the purview of the law. Thus, they argued, a “death with dignity” law would give de jure sanction to what was, in many instances, de facto practice, and would acknowledge the changed conceptual and ethical parameters of the physician-patient relationship.

However, this rationale remains contested a decade after the ODDA became law. For example, the Bush administration led an effort to overturn the act, initially spearheaded by Attorney General John Ashcroft, and then by his successor, Alberto Gonzales; it leaned on the argument that physicians who prescribed substances regulated under the federal Controlled Substances Act, for the purpose of hastening the death of terminally ill patients, were not engaged in medically legitimate actions and should be sanctionable at some level (licensure, prosecution, etc.). This was not resolved in the legal system until January 2006, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Gonzales v. Oregon that federal authority over the regulation of controlled substances did not give the government the power to determine the medically legitimate purposes of drugs that were not otherwise prohibited.

A third justification for the ODDA was a call for processes to ensure democratic responsibility and public accountability. The advocates of the act sought to provide a regulatory framework and a measure of public transparency for the kinds of hastened-death procedures they were convinced were already occurring in secret — without opening the door to the sort of spectacles and publicized abuses carried out by Dr. Jack Kevorkian in Michigan. The procedural criteria delineated in the act — including diagnosis of terminal illness by two qualified physicians, patient decision-making capacity, an informed decision process, reiterated (and revocable) requests, mandatory waiting periods, and permitting physician provision of a prescription but stopping short of physician-administered euthanasia — were designed to assure the public that physician-assisted death could be regulated in a manner that would deter abuses and provide oversight of the responsible actions of individual practitioners and patients.

The ODDA was structured around the three pillars of patient self-determination, professional immunity and integrity, and public accountability, considered individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for legalizing physician-assisted suicide. Each of these conditions has been the subject of moral, religious, professional, and political critique that reached a crescendo in Gonzales v. Oregon and has since abated (although it has been revived by Washington’s I-1000 debate). For example, the annual report of the Oregon Department of Human Services on the statistical frequency and demographic profile of patients was a national news story from 1999 through 2001, receiving widespread coverage through publication in the New England Journal of Medicine. However, by 2007, the annual report was no longer front-page news nationally or even locally; coverage of the report was relegated to the “Metro” (B) section of the state’s leading newspaper, The Oregonian.

Unexpected Results

After a decade of physician-assisted suicide in Oregon, what results do we have from this unique experiment carried out in what Justice Brandeis famously called the “laboratory” of the states? Among the lessons that this past decade holds — lessons that might illuminate the decisions faced by Washington voters — are several surprises.

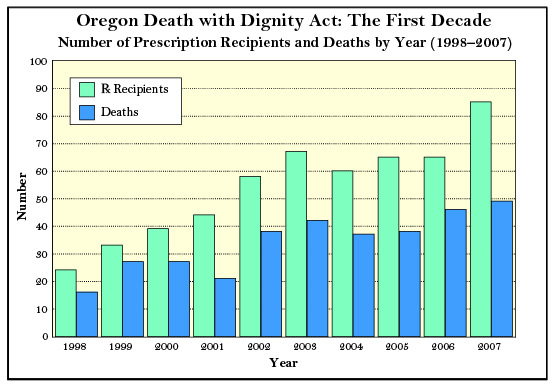

Death with dignity is the death of choice for relatively few persons. Before the act was implemented, opponents anticipated a demographic migration of near-terminal patients to Oregon, such that Oregon would become a “suicide center” for the terminally ill, with all sorts of ensuing social catastrophes. The empirical evidence does not bear out these projections. In ten years, 541 Oregon residents have received lethal prescriptions to end their lives; of this number, 341 patients actually ingested the drugs. These figures are not only lower than the substantial numbers predicted by opponents, they are even smaller than the more conservative estimates anticipated by advocates. While those figures have generally risen each year, the deaths under the ODDA still comprise a very low proportion of Oregon’s total deaths.

Given the predictions of both the ODDA’s original supporters and opponents, one might be inclined to ask not why are some terminally ill patients seeking recourse to physician-assisted suicide, but rather why aren’t more of them doing so? In some years, and in some cases, the prospect of federal intervention may have had a kind of “chilling” effect — if not necessarily among patients requesting such assistance, then on willing physician participants. There may also be a general demographic factor at work: younger persons may be more willing to support physician-assisted suicide than elderly persons who may be staring their own mortality, or that of loved ones, in the face.

However, a likelier explanation may be that the ODDA served as a catalyst to improved end-of-life care among Oregon practitioners — including the increased use of hospice and palliative care, and the easing of restrictions on the drugs practitioners could provide to relieve pain. This is a very significant possibility, because it implies that ensuring a dignified death may not be a matter of changing the laws so much as a matter of changing medical practices and professional education. Moreover, it suggests that, for most people, a pharmacologically-induced death is not a precondition of a dignified death, nor that the possession of a right entails its subsequent use.

Other states have not followed the Oregon model. In the months following its passage in November 1994, the ODDA was heralded as a national model for other states in addressing issues presented by terminally ill patients, particularly as it went beyond the traditional moral and legal boundary of treatment refusal but stopped short of an even more controversial practice, physician-administered euthanasia. Yet, despite numerous efforts — including in state legislatures and by citizen initiatives — Oregon has been more the national maverick than the national model. Although the I-1000 initiative is likely to be approved in Washington, the interesting question is why other states have not followed the path that Oregon thought itself to be pioneering.

For one reason or another, an act like Oregon’s may not be necessary or feasible for many states. First, although suicide has been decriminalized and euthanasia remains a form of homicide in all states, the legal situation is not so clear-cut when it comes to statutes on physician assistance in suicide. Some states do not have specific laws prohibiting physician-assisted suicide; among states that do have such laws, violations may not be reported, the laws may not be enforced, or the participating provider may not be convicted or sentenced. That is to say, substantial discretion and flexibility on these questions are already embedded in the laws of many states. If we understand law to be not simply a social mechanism for restraining wrongdoing but also an educator of social values, it may be that the mere possibility of passing such an act serves as sufficient impetus to find alternatives for improving care at the end of life.

Patients seem relatively free of or immune from coercive influences. In the run-up to its passage, a significant objection to the ODDA was that even though its advocates were using the rhetoric of patient choice and self-determination, patient choices would ultimately reflect compromised voluntariness or even coercion. Put another way, though the act sought to legalize one method for exercising a “right to die,” critics were concerned that patients could subjectively experience this as a “duty to die” for the benefit of family or others.

This perception was reinforced by various studies of physicians’ attitudes towards patient choices. For example, a 1996 study (conducted while the act was being legally contested and published in the New England Journal of Medicine) reported that more than 93 percent of 2,761 polled Oregon physicians believed a patient might request lethal drugs “because of concern about being a burden,” and more than 83 percent believed a patient may make such a request “because of financial pressure.” If these were the motivating factors in patient decisions, contrary to the stated rationale of expanding patient choice and rights, the ODDA could be seen as limiting choice or coercing decisions.

In practice, according to the ODDA data collected by the Oregon government, becoming a “burden” to family and other caregivers emerged as an end-of-life concern for 39 percent of the 341 patients who have used the act in its first decade — a not insignificant number, but still much lower than the percentage of patients who expressed direct self-regarding concerns about loss of autonomy, diminished quality of life, loss of dignity, and loss of control of bodily functions. Less than 3 percent expressed concerns about the financial implications of treatment.

A caveat is necessary here: The demographic information collected by the Oregon Department of Human Services involves reports only from physicians about patient concerns — so the information is second-hand and may not penetrate to the depth of patient motivations that a first-hand qualitative interview might. Moreover, the information compiled from physician reports is generated by a government-issued standardized form that asks the physician to mark any of seven boxes that best reflect the reporting physician’s view of the concerns contributing to the patient’s request for a lethal drug — forcing physicians to use generic categories that may imperfectly, if at all, express their patients’ subjective experiences and motivations. Because of these limitations in the state-sanctioned reporting method, other studies have attempted to more accurately identify the reasons for patient choices. For example, a 2003 study published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine fastened more on patient concerns over “control of the dying process” that had been relayed to physicians, a concept that is intimated but not specifically described in the seven categories on the state reporting form. It is also unfortunate that no empirical research has been conducted on the reasons why most eligible terminally ill patients have said “no,” either explicitly or implicitly by their actions, when it comes to exercising their right to request a lethal prescription.

These considerations notwithstanding, the procedures embedded in the statute for ensuring informed and voluntary decisions by terminally ill patients have been substantially effective. The pre-implementation concerns of critics about coerced or compromised choices do not seem borne out in practice.

“Death with dignity” has been largely normalized in medical practice and moral discourse. The passage of the ODDA in 1994 and its decade of implementation without the dire consequences envisioned by opponents has altered the tenor of discourse about ethical options at the end of life. The question is no longer whether physician-assisted suicide should be permitted within medicine, but how to regulate and monitor the approved processes effectively. Instead of grappling with the fundamental moral questions, commentary about the act now often sticks to the far more mundane questions of oversight and administration. Physician-assisted suicide, no longer novel, doesn’t possess the sharp edge it once had in public, professional, and bioethical debate; it has largely been supplanted by more hot-button issues, such as research on embryonic stem cells or new genetic breakthroughs.

While college students are not the truest gauge of the cultural Zeitgeist, it has been remarkable to me to observe the shift in student attitudes at my state university from 1994 to the present. Prior to its passage, students in biomedical ethics courses considered the ODDA a “burning issue,” a “hot topic,” one that made for a good debate, and a subject for which there were commonly significant differences in opinion. And student engagement with the issue, as evidenced by the number of related term papers, ran broad and deep. By contrast, today’s students, ten years after the ODDA’s implementation, have been acculturated to a “right to death with dignity” as just “the way things are.” They find it difficult to see the issue as morally or professionally relevant, and they commonly wonder what “the problem” is with the other forty-nine states, and why, after more than ten years, Oregon is still the only state with such a law. Student engagement through submitted term papers has declined from nearly 30 percent of students to approximately 3 percent. In my most recent class, not a single student raised an objection to Washington I-1000.

Pain Control, Complications, and Confusion

Some implications of the ODDA’s implementation were easier to foresee, including the general improvement of pain control, the overall lack of medical complications resulting from the lethal drug, and an ongoing confusion about how the act works in practice.

Palliative care and pain control emerged as a paramount focus of end-of-life care. As described above, the supporters of the ODDA in the 1990s often invoked “hard cases” — nightmarish scenarios of terminally ill patients tortured by unrelenting pain. This rhetoric was intended to evoke public sympathies towards the plight of persons whose condition made them very vulnerable, as well as dismay — if not outrage — at the apparent indifference in the medical system, religious communities, and the law towards such patients. The implication was that these patients were destined to live out their final days either tethered to technological life support (and perhaps unconscious) or in substantial pain, unless the ODDA became law and professional compassion joined with respect to enable a hastened death.

In fact, the passage of the ODDA led to a greater effort on the part of physicians and palliative and hospice care teams to ensure adequate pain control. A Task Force to Improve the Care of Terminally-Ill Oregonians was established to bring greater awareness to the question of pain management immediately following implementation. The task force issued an influential report in 1998 that practitioners still rely on a decade later. Institutions involved in pain management developed new protocols, and laws that had raised the prospect of licensure investigations of physicians who provided more pain medication than called for in conventional medical protocols were rescinded. Thus, physicians no longer faced a professional and legal deterrent against the use of personalized pain control methods.

As noted above, the lower-than-expected number of patients requesting lethal drugs can likely be attributed in part to these improvements in the quality of pain management. And even the patients who requested and used lethal prescriptions — recall, 27 percent of those 341 patients said they were worried about inadequate pain control — may not have been experiencing pain in their terminal phase but rather anticipating and hoping to avoid a painful death.

The lethal drugs are largely without additional medical complications. A central argument of opponents of the ODDA was that through the prescribed drugs, physicians would be exposing their patients to substantial risks of harm, including severe complications, lingering deaths, and unintentionally induced comas. This claim was emphasized because there was (understandably) no reliable body of medical evidence on what drugs and dose ranges would bring about a patient’s death without complications. Thus, it was argued, rather than benefiting the patient by providing the means to a hastened death, the patients would risk continued life in a “worse-than-death” condition — in which case the prospect of euthanasia, which was a violation of the statute, would be necessary to end life.

This fear seemed overstated at the time, drawing as it did on disputed anecdotal accounts from the Dutch experience with physician-assisted suicide and physician-administered euthanasia. Indeed, the implementation of the ODDA indicates that those concerns were unfounded. According to the physician reporting system, almost 95 percent of patients have experienced no complications; just over 5 percent of patients have initially regurgitated the lethal dose. There have been no interventions by emergency medical services, and the time frame between ingestion of the prescription and death has ranged from as short as one minute to as long as three and a half days, with the median being 25 minutes. It would be useful to know the minimal and maximal time frames beyond which a patient can be said to have experienced “complications,” because disclosure of such information is necessary to any authentic process of informed consent — but unfortunately the state reporting system does not assess this.

In this regard, it is also important to ask who would determine if complications of one sort or another had been experienced by the patient. In only 28 percent of the patient deaths has the prescribing physician been present at the time of patient ingestion of the lethal dose, and in 19 percent of the cases, no health care provider has been in attendance. In the remaining 53 percent of patient deaths, some provider besides the prescribing physician has been present at the time of ingestion.

The case for physician-assisted suicide as a safe and effective procedure with minimal complications would be strengthened if the prescribing physician, or at least the reporting physician, was present at both the time of ingestion and the time when death was declared. If the median time frame from ingestion to death is 25 minutes, it seems not too much to ask a professional to be present with the patient. Even if there are no complications, it would still be a profound gesture of presence and commitment to remain with the patient to the very end. And in circumstances where the actual time frame is not 25 minutes, but pushing 25 hours, or even 83 hours, continued monitoring by the professional would seem to be a necessary element of care.

Citizens can be confused about their rights and options regarding end-of-life choices. Despite all the legal and educational efforts seeking to inform Oregon residents of their rights and options pertaining to end-of-life choices, there remains a good deal of confusion, at least as expressed in public gatherings and discussion forums.

The state has two forms of advance directives, which can be used independently or in conjunction with each other, and which are comprehensive with respect to termination of medical treatment or appointment of a proxy. However, these advance directives are separate from the ODDA application process: terminally ill persons seeking lethal drugs must use an additional request form specific to the provisions of the act. An advance directive that includes a request for physician assistance in dying is unlikely to be honored. This is a point on which there seems to be significant confusion. Although there seems to be broad public consensus that certain kinds of death can be degrading and demeaning to dignity, and most people seem to want to avoid a persistent vegetative condition or a Terri Schiavo-like death, it is not clear in the minds of many citizens that the advance directive process that would apply in those circumstances is separate from the physician-assisted suicide process. There remains a compelling need for public education.

The Experiment’s Unanswered Questions

When the Oregon Death with Dignity Act first passed, it was heralded by some commentators as a “bold experiment.” The first decade of that experiment’s results are in: it seems that the practice of prescribing lethal drugs to terminally ill patients is effective and generally without further medical complications. Consequentialist objections to the act have largely been refuted by experience. Insofar as objections continue to be voiced by various advocacy groups or medical practitioners, they tend to rely on non-consequentialist appeals to the intrinsic value or sanctity of human life, or to the moral vocation of health care professionals. Similar consequentialist arguments have been articulated against Washington I-1000 — but if experience is any guide, they cannot be long sustained. Moreover, since public policy (including health care policy) primarily depend upon utilitarian assumptions, it will be very difficult for non-consequentialist principles to gain much footing in debates over legalization.

That said, as a matter of public policy, physician-assisted suicide measures are always open to evaluation based on continuing experience. There are three broad ongoing questions about the Oregon experience that are relevant to the current debate in Washington over I-1000 and that will be relevant to future discussions in other states.

First, what is the nature of the patient experience? Advocates for the ODDA and its imitators in other states have based their arguments on the principle of patient self-determination, but even after a decade we know relatively little about the determining self of the patients who request lethal drugs; their reasoning processes and worldviews are largely opaque. This lack of transparency is partly attributable to necessary protections for confidentiality and privacy (both for patients and providers), but it is exacerbated by a state reporting system that filters patient experiences through physician perceptions and voices.

The voice of patient experience is further attenuated by the state-imposed template that limits the responses physicians can offer. To be sure, the reporting categories help to efficiently quantify results, but they are qualitatively inadequate. The literature on death and dying since the days of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross has revealed an emotional and cognitive experience of dying patients that centers on a fear of abandonment, or an increasing sense of isolation, or a process in which a kind of social death precedes the biological death. However, there is no place on the state report for physicians to even mark a box that alienation, estrangement, or isolation may have been motivations contributing to a patient request — let alone room to go into any depth on the patient’s mindset.

A disturbing October 2008 study in the British Medical Journal indicated that 16 percent of patients who requested a lethal prescription under the ODDA from 2004 to 2006 suffered from clinical depression but were not referred for counseling as the law requires. For a statute that is promoted explicitly through the rhetoric of patient self-determination and choice, such findings present a substantial concern that the ODDA may not provide sufficient protection for some vulnerable patients. This study, coupled with the generally opaque patient experience, raises the possibility that physician-assisted suicide is a quick fix for the wrong problem. If the patient requests a lethal prescription because of fears of abandonment or isolation or depression as he or she dies, or even certain metaphysical or spiritual concerns, then it is the social, psychological, relational, or philosophical context that needs to be attended to, and not only the patient request. As things currently stand, however, the nature of the patient experience is badly diluted and filtered, and the dead tell no tales.

Second, what constitutes a “dignified death”? It is very difficult to know what ethical significance, if any, to attribute to an act that contains the value-laden term “dignity” as part of its title and public legacy. The meaning of the term was left completely unexamined in the political context of the act’s passage and in the subsequent political discussion, revealing an impoverishment in moral discourse about human dignity generally and about dignity in death specifically. It is indicative of this moral impoverishment that despite its oversight responsibilities for the ODDA, the Oregon Department of Human Services did not, in its reporting form, even ask whether a concern about a “loss of dignity” was a contributing factor in patient requests for lethal drugs until after five years of implementation. During the years those questions was asked, from 2003 to 2007, 82 percent of patients are reported by physicians to have expressed concerns about diminished dignity in dying. That should come as no surprise; in fact, the surprise is that the figure isn’t closer to 100 percent.

However, the figure remains relatively meaningless since we do not know what patients (as reported by their physicians) mean by the term “dignity.” When I ask about the features of a dignified death in public forums, the question typically fails to start discussion — either because citizen participants have not thought of “dignity” in any terms other than this politicized context, or because its meaning is so patently obvious that the answer shouldn’t need stating: that dignity refers to patient control over dying, and especially patient “choice” over the manner and timing of one’s death. Dignity is thereby reduced to a notion of autonomy.

This truncated understanding of dignity as a matter of personal choice is an example of the impoverishment of our moral discourse. Certainly, there are scholars who have sought to provide more robust and substantive accounts of dignity, and the President’s Council on Bioethics is to be commended for taking on the subject in its recent anthology Human Dignity and Bioethics. But wherever the philosophical and bioethical discussion stands, the civic discussion remains badly muddled by the confusion of autonomy and dignity.

Finally, in what does the integrity of medicine as a profession and moral vocation consist? Longstanding tradition has affirmed medicine as a vocation directed toward the good of healing, and that tradition has generally taken healing to be incompatible with physician facilitation of death or killing of patients. There is little question that healing presumes a responsibility to end or ameliorate pain or suffering, but that did not by itself warrant permission to relieve suffering by ending the life of the sufferer. A second tradition, extraneous to medicine, needed to be invoked to make this step morally, and within bioethics that tradition was found in the resources of political liberalism, with its powerful corollary of patient empowerment and respect for patient choices.

In many circumstances, the goal of healing coincides with a respect for patient self-determination, but not always — as the case of physician participation in hastening death seems to show. This formed the broad philosophical context for the Bush administration’s specific objections to the ODDA — that physician prescription of controlled substances with the intent to hasten a terminal patient’s death was not a legitimate purpose of medicine; in short, that such actions violated the ethical integrity of medicine. In its Gonzales decision disagreeing with the administration, the Supreme Court did not really address the issue of how medicine coheres as a profession when it is shaped by both a tradition of healing and a tradition of respect. We would not say that the role of a medical professional is to do whatever patients or health care consumers request; that understanding would eviscerate the concept of “profession” altogether. Alternately, we would not want to vest all moral authority in the relationship of physician and patient in the physician because of a presumed commitment to healing — thereby reviving the tradition of medical paternalism or empowering physicians to make every possible use of conscience clauses anytime there is a disagreement with a patient. A crucial task for the medical profession and its interpreters in the wake of past and current proposals for “death with dignity” is to recompose its vocational (and sometimes personal) integrity in light of these at times contradictory traditions.

A brief personal assessment in conclusion: I have argued in the past that the Oregon Death with Dignity Act was a moral mistake. I have never agreed with the objections based on consequentialist catastrophes, but rather my opposition stemmed from a moral framework that permits the taking of human life — whether that be in self-defense, capital punishment, war, or end-of-life care — only as a last resort, and it has not seemed that society, or the state of Oregon specifically, had exhausted all alternatives — including better pain control, more and earlier referrals to hospice care, and effective education on advance directives — to achieve the goals of end-of-life care such that the last resort condition was satisfied. After a decade of living in a state where physician-assisted suicide has gradually reached the point of eliciting a “ho-hum” in the newspaper, I find myself still affirming that there are other ethically preferable policies to achieve patient choice, control, and “dignity” in the end of life, even while recognizing that individual patients do sometimes find themselves confronted with the need to employ that “last resort.”