October 21, 2016

Since at least Dante, the poetic vision of destiny in the West has bound up together love and the heavens. In this sense our highest poetry worked to reconcile and harmonize the personal at its most intimate and the natural at its most cosmic — in Dante’s case, through the Divine. That sort of poetry could be described as a practice of the art of humanism, properly understood. Yet strangely, despite remarkable leaps forward in spacefaring technology that promise to unite the personal and the cosmic in an epochal way, today’s Western vision of destiny has become fractured and contested. It is no longer accepted belief that poetry, divinity, destiny, and the personal love of being human are all constituent parts of a harmonious experience of being.

This problem — and it is a problem — is encapsulated in the uncertain place of Mars in the human conversation today. That conversation is dominated by matters of politics, science, and economics. Though it is obvious that these things should play a role in how people wrestle anew with the age-old question of our relation to Mars, something is badly and historically amiss in the absence of love, humanism, and poetry from these conversations. It is no excuse that ours is a time of fantastically powerful governments and technologists, one in which money, moreover, threatens to become the measure of all things. If the public imagination regarding Mars has been dimmed in the West, it is on account of our failing memory of the ancient role of the cosmic in practicing the art of humanism, and the failure of our poets to access and rehearse that role anew, amid conditions that ought to be recognized as hugely favorable.

The difficulty is not just one of disenchantment, although a disenchanted and unpoetic view of Mars will pose great difficulties. The disenchantment of Mars signals a deeper and broader disconnect with, and alienation from, the humanist wellspring of poetry: the love of being human. The antihumanism welling up in today’s utopian and dystopian visions of technological destiny not only pulls our view down from Mars, the cosmos, and the heavens; it turns our view against ourselves. Our technological destiny shifts from one in which human life radiates outward from Earth to one wherein humanity is so rotten that our future must cease to be human at all, whether by becoming subhuman or superhuman.

Western poets have drawn upon love to teach by example the art of humanism. They have used love to help us make sense of our place in the world — longing for home yet eager to wander — and in that way, of the whole physical reality that surrounds us and situates our life, on Earth and beyond. Since Mars is part of that landscape, restoring a truly humanist vision to the question of our Martian destiny means regarding Mars in terms of love. Rather than limiting ourselves to the political, scientific, and economic questions about the use and advantage of Mars, we must also ask the poetic question about the presence of love in our relationship to Mars. Is not Mars so special and so ripe with specific possibility, waiting for us and the fast approaching moment when we might settle it permanently, that we are obliged to speak of Mars with love, in love? Would we not speak wrongly, even falsely, if we spoke any other way of the only place available to us to make our first home away from our home planet?

We have lived already as humans over the millennia in a relationship of love with Mars, a relationship we might once again intentionally cultivate. It reaches back well beyond Dante — to antiquity, when the deity Mars was not only the familiar warrior god but also the venerated protector of the farmer and the shepherd. Many scholars, such as Alberta Mildred Franklin in Lupercalia: Rites and Mysteries of Wolf Worship (1921), believe that Mars absorbed an earlier wolf-deity. But by Roman times, although Mars sometimes appeared in art and literature in the form of a wolf, “the wolf lost much of his savage character, and became a helpful animal that guided colonists on their way.” It was a she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome and children of Mars. The divine Mars embodied life in its warlike and wild aspect, but as a protector of and guide for life in its home-building, home-preserving aspect.

By the Christian era of Dante, of course, the pagan provenance of Mars as divine was subsumed within the cosmos of divinely furnished celestial spheres. The poet did not envision the literal, physical unification of human life with the celestial order. His aim was to dramatize the unity of the human and the celestial as not a manifest but a spiritual destiny. But Dante’s poetic placement of the cosmic and the human realms into a shared and intimate poetic relation with divine love helped set the stage for later thinkers to see the planets less as “wandering stars,” as the ancients did, than as elements of the human realm.

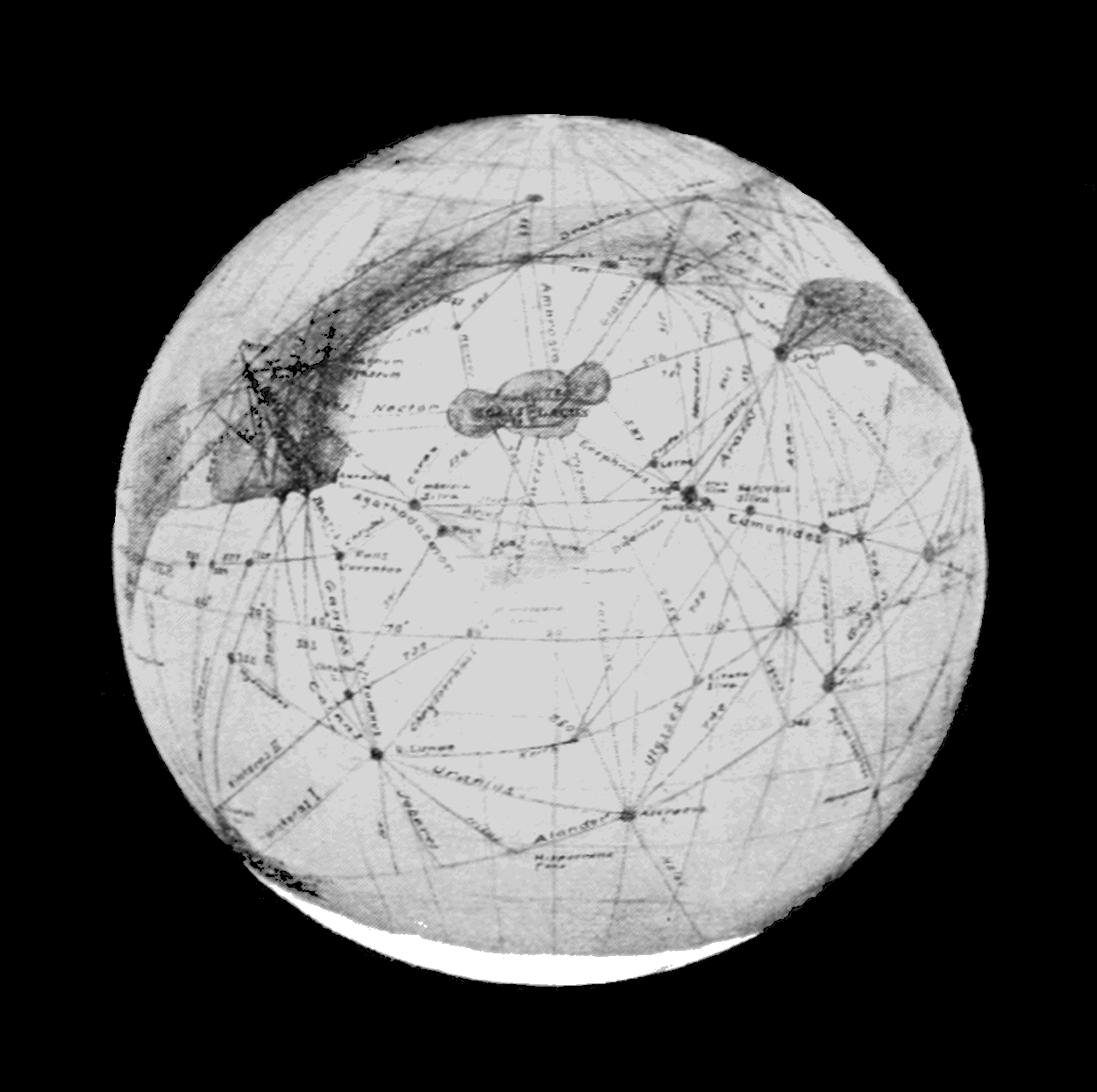

Mars was brought closer to Earth through advances in physics, astronomy, and telescopy. Copernicus and Newton brought the heavens at large closer by showing that we are ourselves one of the celestial bodies, and that the laws governing their motions are the same as those governing motion for us. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Mars became a focal point of a new fanciful but authentic reunion of science and the humanities around our cosmic relation. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli began to trace Mars’s topography, including channels of water, which he called “canali.” The word was mistranslated into English as “canals,” suggesting the possibility of intelligent life and artificial structures. The American astronomer Percival Lowell thrilled to the prospect of canals on Mars and drew his own detailed sketches, published in 1895, complete with speculations about Martian beings.

In 1908, about a decade after War of the Worlds, which famously featured invading Martians, H. G. Wells wrote an elaborate “non-fiction” inquiry into Martian life, called “The Things that Live on Mars,” for Cosmopolitan Magazine. Illustrated by William R. Leigh, painter of that other grand frontier, the American West, Wells’s speculations were based on Lowell’s. He imagined, as the caption of one image put it, “a jungle of big, slender, stalky, lax-textured, flood-fed plants with a sort of insect life fluttering amidst the vegetation,” along with “ruling inhabitants” of “quasi-human appearance” and “human or superhuman intelligence” who built the canal system. Though fears of alien civilizations invading Earth haunted science fiction in the early twentieth century, the more enduring response to Mars was one of wonderment and fascination at the idea of life extending into the heavens.

Since the time of Wells, many of our best science fiction authors have kept the reality of our relationship to the cosmos alive in the public imagination. In recent decades, the likes of Kim Stanley Robinson and Andy Weir have brought to sci-fi a psychologically balanced and mature approach to the challenges and possibilities of extending humanity’s reach to Mars. The sensationalism and dark fantasies of earlier books and movies has been eclipsed by more literarily serious work. If Mars has not explicitly represented love in this work, it has still evoked a kind of attention concomitant with love — one in which the joyful embrace of creation as humanity’s home inspires intimate visions of cosmic destiny. Yet sci-fi has not been constitutive of its culture in the way that Dante’s work was, but rather the niche culture of the nerds, evoking from the rest of society little more than smirks when it is noticed at all.

Today, within plausible voyaging reach, Mars can at last be regarded as a real place, serving as the unique site where we can begin to fulfill the promise of our bodily settlement of the cosmos. In that way, the Red Planet bears unique witness in favor of the poetic case for preserving the good news of our humanity no matter how robust our technological development.

To love Mars is not to embrace some abstract romantic vision. To the contrary: Mars is attractive and particular, and should impress us with the remarkable concrete features that define its scope of possibility.

Mars is the second closest planet to Earth, farther than the beautiful but profoundly inhospitable Venus and much farther than the closest heavenly body, the Moon. It is a “fixer upper” as a home for life, as Elon Musk puts it, but its tundra climate is neither as terrifying nor as toxic as that of our closest neighbor. With its ice, soil, atmosphere, and possible history of life, Mars is neither an uncanny clone of Earth nor incomprehensibly alien. It is within reach, but only with effort and dedication — too far to be conveniently near to us, but too near to be prohibitively far away.

Moreover, it has simply been there, forever, for us to regard, a luminous red wanderer in the beautiful middle distance where love is characteristically awakened and where, in rich moderation, it matures. Mars is easy and reasonable, but not too easy and reasonable, to love. Mars is remarkable and wonderful, but it is not perfect; it does not quite exude greatness, but it partakes of the grandeur of the cosmos that shapes us and the grandeur of we humans who have embraced it in our earthly vision. Mars is a free world, an ancient world that invites us to make it new. And it is at hand.

These attributes can be discussed in purely rational, instrumental, and material terms. But there is no good reason to do so. In fact there are many good reasons, including the not-so-rational foundation of human experience in mimesis and memory, why we must not do so.

Mars is distinctively worthy of commanding our attention and arousing our eros. It invites our love as a uniquely suitable home away from home. It reflects our love for the cosmos as a place of salutary, edifying challenges, where given limits and constraints create the very possibilities of our growth and flourishing. And it reminds us of the practical virtues of loving our human condition — limits, constraints, and all. In these interrelated ways, Mars shines as an ideal but very real subject for us to dedicate ourselves to in demonstration of some of our most distinctively virtuous human practices. It shows how the cosmos is our proper home, a well-bestowed setting for the civilizing and life-sustaining enterprise of home-making.

The choices we make and the agency we exercise toward Mars will set the tone, and lay the groundwork, for the rest of our human history in the cosmos. Even were we to give our best-intended rationalists, instrumentalists, and materialists complete sway over political, scientific, and economic matters, the question of whether or not to remain fully human — and the function of bodily interplanetary settlement as a means to channel tremendous technological development into the enterprise of remaining fully human — could not be comprehended. And even if humanism remains incompletely religious in its character, the poetic tradition that holds being human as good and good enough will be essential to comprehending all that is truly at stake in choosing how to live with, and how to love, the Red Planet.

Indeed, by understanding that love of Mars and love of being human go hand in hand, we stand to break the grip of antihumanism, whether religious or secular, over the political, scientific, and economic controversies of the age. We will reopen our eyes and hearts to the kind of love we need to flourish not only on the Red Planet and beyond but here at home, on Earth.

It is a compelling image that helps us understand why tech backlashes, however powerful they may sometimes appear, never amount to much. It may be too late to refuse the bribe altogether — but we would do well to understand its terms if we are to make sense of our situation and the possible futures available to us.

Our public and private minds and hearts are reverberating with the voices heralding that the news of humanity and Earth is bad. These antihumanist voices are loud and diverse. Some speak in expressions of dread. People dread the Trump administration. People dread another world war. People dread a fresh economic or environmental or other kind of catastrophe. Dread-mongering encourages us to feel certain that something big and awful beyond our control is definitely coming, even if we can’t be sure what it is or when it will arrive. The intellectual landscape is filled with such voices.

Even more influential than expressions of dread are expressions of loathing. Much of the most recent presidential election was about who you loathe — not just who you deplore or who disgusts you, but who actually makes you feel worse about being human. This is becoming the political norm, the means by which group identity is formed and given agency. Turn on the news, log on to Twitter: The message that the horrible people are winning, polluting society, and dragging us all down dominates, cutting across all ideologies. Beneath the sense of smugness and superiority it breeds, it nurses a creeping conviction that the world’s growing class of bad people — defective, repulsive, loathsome — actually proves that we should not love being human. Perhaps we should fear and loathe it.

Retreating into the confines of our own friends, families, homes, and handheld devices does not alleviate this feeling. It often worsens it. Expressions of what classical and medieval thinkers called acedia — a depressed, melancholic boredom and disinterest in being human — are on the upswing. Aldous Huxley wrote an essay about it, titled “Accidie.” Kathleen Norris wrote about it in her 2008 bestseller, Acedia & Me: “The demon of acedia — also called the noonday demon — is the one that causes the most serious trouble of all.” Norris quotes from the writings of a fourth-century monk, who says that the demon “makes it seem that the sun barely moves, if at all” and “instills in the heart of the monk a hatred for the place, a hatred for his very life itself.” More than just seeing others as proof that to be human is to be unlovable and that Earth is a fundamentally bad place, we begin to see that proof in ourselves as well. Monks may struggle against acedia in their isolated, ascetic lives as they work to achieve a state of spiritual joy — “ascetic” is a word derived from the Greek for “exercise.” But our forms of rigorous self-isolation lack spiritual discipline. They turn us into workaholics, Internet addicts, hoarders, and hermits, or the just plain lonely.

So we’re pushed toward the option of greater worldliness — chasing after the supposedly great things of life, like notoriety, novelty, success, wealth, power, and so on. Unfortunately, what we discover is that inside the gleaming enclosure of greatness is a rotten center. We begin to feel bitterly like the Satan of Biblical allegory — born to fall. How could we choose love when everything around and inside us is bad?

Amid these antihumanist voices, people tend toward two options. The first is an increasingly fanatical devotion to the idea of using power to break human limits and to force perpetual progress. In The True and Only Heaven (1991), the Marxist-influenced communitarian Christopher Lasch condemned this “progressive optimism” for its “denial of the natural limits on human power and freedom.” He championed instead a humanistic “state of heart and mind” that “asserts the goodness of life in the face of its limits.”

But those following Lasch who are sharpest in their criticism of the ideology of excess often now veer toward counseling the opposite — a surrender before the apparent rot of the world and a determination to abdicate power, retreating into circumscribed shelters with low but stable horizons. For them, modernity is increasingly becoming, perhaps has always been, an exercise in fatal self-deception about what humans are capable of. Modernity must be rejected accordingly, with all the costs attendant on such a radical ethic of honesty.

The most prominent, albeit limited, example at the moment is the “Benedict Option” espoused by Rod Dreher in his 2017 book of that name. Although the Benedict Option does not call for the kind of monastic isolation the name suggests, and of which it’s often accused, it does, as Dreher explains elsewhere, describe “Christians in the contemporary West who cease to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of American empire, and who therefore are keen to construct local forms of community as loci of Christian resistance against what the empire represents.” The idea and the name derive from the closing passage of moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre’s 1981 magnum opus After Virtue. MacIntyre has since argued that the liberal order of an integrated national state-and-market undermines the cultivation of virtue and appreciation of the full human good, implying that we should put our energy into school boards and local unions rather than federal politics.

For ex-liberals like the philosopher John Gray, for example in his 2013 book The Silence of Animals, the best hope for humans, it appears, is to behave more like certain particularly calm beasts, or perhaps even trees and rocks. “The hope of progress is an illusion,” Gray wrote in Straw Dogs (2002), and “humans cannot save the world.” And this is just fine, because the world “does not need saving.” But for Gray we don’t escape human problems by retreating from society: “A zoo is a better window from which to look out of the human world than a monastery.”

In one sense, these moves are wise hedges or side bets for any culture curating a diversified portfolio of approaches to life. But they are no Plan A, and a Plan A is what is needed above all. In fact, some of the contemporary criticism of progress is itself oddly progressive, with idealists wanting to “get beyond” peak oil, peak Apple, or late capitalism as a whole. Here is a lot of the left neo-Marxist literature. But much of it is also fairly reactionary — insisting that we have to more or less reject Francis Bacon and René Descartes, the founders of modern science, heal the break they made with the ancient wisdom, and go back to embracing humanity’s humble natural stature and fear of transcending it.

These can be deeply Christian prescriptions, focusing as they do on the ways in which modernity can be inhospitable toward the life of Christian virtue. But, as others have pointed out, they tend to cede too much ground to the antihumanists. Nietzsche worried in The Genealogy of Morals that conventional conceptions of being good may lead to “forgetting the future,” that they can be a kind of “retrogression.” And Machiavelli was right to be frustrated with the Christianity of his time, which too often worked to strengthen people only for passive suffering and inwardness.

The temptation to affinity with antihumanism, however, is not generally true of Christianity today — especially in the New World, where religious people are typically among the most realistically enamored with being human, warts and all. A meditation on the upshot of this phenomenon ripples below the surface of Charles Murray’s Human Accomplishment (2003):

Human beings have been most magnificently productive and reached their highest cultural peaks in the times and places where humans have thought most deeply about their place in the universe and been most convinced they have one. What does that tell us?

Our search for that which is worthy of love in our humanity is more likely to lead us back to the times and places Murray refers to than to the ancients and medievals as an answer to antihumanistic modernity and postmodernity. Yet thinkers who attempt to tie cultural and political and economic flourishing to kindling a love of humanity are often cast as villains, perhaps as seekers after militaristic “greatness” projects — many view the Apollo program this way.

Despite our huge advances in technology and knowledge, only a few remarkable frontiers seem to exist any longer, and those that do, like radical life extension, seem to be the outlandish province of the privileged few. For the rest of us, exploration and adventure seem increasingly restricted to playing small-stakes psychological, sexual, and identitarian games of power, online and off. With so much earthbound loathing and lassitude, no wonder so few love Mars. Yet here Mars awaits, ready to offer us exactly the kind of frontier we think we’ve lost, or don’t deserve.

For centuries, following the ancient Greek tradition, it has been true, to borrow a line from Led Zeppelin, that there’s a feeling we get when we look to the West. The frontiers of our geography and our imagination converged. The West is where the sun sets, the West is where the ancients had to turn after the collapse of Alexander the Great’s attempt to unite it with the East. The center of gravity and power in the Western world has moved steadily west over time, and Western theorists and seers have attributed cosmic significance or agency to that movement. In his 1980 book History of the Idea of Progress, Robert Nisbet, extending a claim of Loren Baritz, noted that the Greeks and the Romans thrilled to the spell cast by fabled lands to the west. Saint Augustine “claimed divine sanction for his belief in the westward course of empire,” and Thoreau later rhapsodized that “eastward I go only by force; but westward I go free.”

In places — including the most ardent Mars advocacy — this frontier view of our traditional essence has persisted right through to today. In The Case for Mars, aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin (a contributing editor to this journal) outlines in detail his Mars Direct plan, a far cheaper and more practical plan than any available when the book was first published in 1996, and offers an economic, political, and humanistic vision for why we must colonize. He closes the book with an appeal to recapture the American frontier spirit, invoking Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous frontier thesis of 1893 — an “intellectual bombshell,” as Zubrin puts it. “Everywhere you look, the writing is on the wall,” Zubrin warns in his final pages:

Without a frontier from which to breathe new life, the spirit that gave rise to the progressive humanistic culture that America has represented for the past two centuries is fading. The issue is not just one of national loss — human progress needs a vanguard, and no replacement is in sight.

Elsewhere, the founding declaration of the Mars Society, which Zubrin established in 1998, lays out the central reasons we must undertake the mission, including:

We must go for our humanity. Human beings are more than merely another kind of animal; we are life’s messenger. Alone of the creatures of the Earth, we have the ability to continue the work of creation by bringing life to Mars, and Mars to life. In doing so, we shall make a profound statement as to the precious worth of the human race and every member of it…. We must go, not for us, but for a people who are yet to be. We must do it for the Martians.

I find little to differ with in Zubrin’s vision, so similar in substance as it is to my own of the essential connection between our love of being human and our cosmic destiny. Yet it is worth pondering why Zubrin’s decades of arguments — he is probably the most influential and credible Mars advocate of our time — have not dramatically changed the prevailing attitude of the wider culture outside of the scientific community, and even inside that community have not totally done away with the attitude that sneers at human space exploration as hubristic, preferring to send robots in our stead. It must be asked, in other words, why the invocation of the frontier apparently no longer carries the force in our culture that it did in Turner’s day.

Georgetown political theorist Joshua Mitchell, echoing Tocqueville, argues in The Fragility of Freedom, “What is there at the beginning, in the Puritan mind, shapes the future course of American identity” far more than “the kind of character formed by the confrontation with the primitive frontier.” That is, the ultimate origin of the grand frontier of the American imagination was already there, as part of our collective cosmic vision, before anything like the history of manifest destiny played out in the unsettled West. The frontier’s presiding presence in our imagination is the product of the love of being human found in gratitude for being created as we are — in love, a love which calls us, as the late Peter Augustine Lawler liked to put it, to wonder and wander.

Perhaps the problem, then, is that a case for Mars made in terms of engineering, economics, and politics, even when imbued with humanism, will not broadly reorient our collective spirit toward the momentous majesty of our cosmic destination until the case is written in humanism’s native language. Though the tickets for our Martian voyage will be written in prose, the travel brochure must be written in poetry.

When we fall out of love with being human, our longing to embrace the grand frontier — and our ability to perceive grandeur and frontiers at all — will fade. Mars is already inextricably bound up with our destiny — not in virtue primarily of our science or our reason, but of its remarkable pride of place in the cosmos, as the cosmos comes into view for us as lovers of being human. That love lost, however, Mars will be lost along with it.

There is a history of how our love for being human faltered with the closing of the frontier. Without launching into space — or turning radically inward — it seemed impossible for the West to go west of California. Unsurprisingly, California became a place where the West did both — sometimes at the same time. California’s turn upward into space, through Jet Propulsion Lab co-founder Jack Parsons and his co-occultist, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, was intimately connected with California’s radical turn inward, focusing on wellness, expanded consciousness, psychedelics, yoga, and food and wine. That culture, which culminated in the development of the Internet and digital life as the ultimate way to open the doors of consciousness, was lambasted early on in “The Californian Ideology,” a prophetic and polarizing 1995 essay by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, media researchers at the University of Westminster.

Today we are seeing massive anxiety around the limits, disappointments, and pathologies of the Californian ideology. It now appears to be in danger of failing the defining myth of the West. California’s mastery over the West has not reproduced the true frontier experience — in its naturalness, its arduousness, and its bounded openness — from which we drew our experience of grandeur. Today it’s that frontier we still pine for. Too many of our West Coast tech “leaders” are following the rest of us into the habit of making merely private futures, drifting toward a virtual horizon with no discernable frontier.

What happens when these anti-pioneers arrive at the dead ends of their journeys into infinite inwardness? The antihumanists are sure they have the answer. But too many “innovators” today seem to be clueless. Those few who are leading crews back outward toward Mars, and a cosmic destiny, are still seen largely as a breed apart — or worse, as cynical, self-interested marketers using public money to hawk pie-in-the-sky boondoggles. Our suspicion of the limits and follies of greatness is sound, but we are too timid in refusing to look through that apprehension toward the grandeur beyond. To find a new shared frontier, one imbued with grandeur, we need to return to the physicality and particularity of love among concrete, tangible worlds.

Unfortunately, the antihumanists are not the only ones who have soured us so much on our circumstances and character that we have lost a love of life and its grand frontier. Some self-styled or would-be humanists have seen technology as a tool to help us perfect the most comfortably humane lives imaginable — with digital assistants and slave bots knowing what we want before we ask, and giving it to us on the cheap. Techno-plenty will end scarcity, conflict, work, anxiety, and involuntary competition, leaving us to revel in an Elysium of health, safety, and pleasure. Here already on the best of all possible worlds to come, why would we ever leave?

And these are not the only humane utopians on the block. Others, instead of perfecting comfort, want to focus humanity on perfecting pride or perfecting justice. The master science is the one that empowers people to choose, define, and transform their own identity — by augmenting their intelligence, biohacking their bodies, altering their DNA, or optimizing their consciousness. Or the master science is the one that can determine what is due to every claimant of rights and recognition — by creating and implementing algorithms complex and sophisticated enough to officially determine who is owed exactly what by exactly whom at any given moment in political and economic life.

The Californian ideology gave way to these distorted dreams of perfection — which, in a bitter irony, command the greatest of devotees in the California of today. Then again, perhaps it’s not so ironic. Perhaps “humane” Californian culture has devolved into fantasy and utopianism, disconnecting us from the possibility of loving the truly human.

Consider the way California-produced fantasies have hastened us toward strangely inhuman utopias. In retreat from the Space Age, we have turned technology inward, in what tech theorist Paul Virilio describes in The Administration of Fear (2012) as a “masochism of speed.” No wonder California has buckled us into a world of blockbuster superhero “catastrophe porn” movies — total fantasy projected onto a hapless and stagnant landscape where the death of one demigod is a melodramatic tragedy but the death of millions of obscure humans is background. No wonder that the market for tame, safe lives on technological autopilot — reactionary nostalgia wrapped in “disruptive” and “innovative” marketing — is so robust. And no wonder the two leading utopian fantasies of escape from crisis and acedia pull us in opposite directions — turning superhuman or posthuman on one end, and turning petlike, botlike, or otherwise subhuman on the other.

What is conspicuous about both utopias is that they do not involve recognizably natural human beings spreading life as we know it to alien planets. One utopia sends us ever inward toward subhuman lives where technology perfectly satisfies our appetites for health, safety, comfort, and pleasure. (Few yet champion this idea explicitly, but many push it through politics, technology, and art alike.) The other utopia sends us ever outward toward super- or posthuman lives, where we merge with technology into a new lifeform that controls time and space in a godlike manner. (Here the transhumanist champions are quite explicit.)

Both of these utopias reject what a love of Mars would promise: the extension of recognizably natural human life, with its grand narrative, frontier, and destiny intact, beyond the surface of the Earth, and eventually far, far away. Both reject a love of being human, reject being human as good and good enough.

In charting the rise of these utopias and understanding why they resonate strongly, we should see that our cultural turn away from risk, and our obsession with reducing suffering, have primed us to build stagnation into our regime and then get anxious about it. We say we hate the status quo, yet we are terrified of involuntary or natural disruption. So our imagination turns toward the exploration of endless safe inner horizons, or toward a disruption so sudden and complete that we skip ahead all the way to being virtual gods. Humanism today must guide us toward the mix of humility and pride: We need to master technology without trying to replace nature or human nature. And since, as the poets know, love teaches by example, so too should the humanism we need, focusing our hearts together with our minds — perhaps even including our souls — on a particular goal that allows us to experience well-balanced humanity and orient our activities and practices around it. That’s where Mars cannot help but come in.

This approach offers a salutary escape from the dead ends we reach when we turn to technology as a utopian tool that can humanely “perfect” us right out of our humanity. Anti-utopian guides — from heterodox libertarian economist Tyler Cowen in The Great Stagnation (2010) to journalist Jacob Silverman in Terms of Service: Social Media and the Price of Constant Connection (2015) to computer scientist Jaron Lanier in You Are Not a Gadget (2010) — point up the wisdom of some humility on the one hand and some pride on the other. To infuse those kinds of basic insights with the grandeur we need to resist our competing dehumanizing utopias, however, we need more than good economics, good politics, or good criticism. We need messengers carrying a vision of love for humanity.

Today, we have largely allowed technology to fragment that vision. We struggle even to love people more than a few generations removed from our own. But there is now a generation young enough to avoid the aimlessness and anxiety of the millennials who came of age into a world of great technology and little confidence. It’s important to take stock of their point of departure. It is more likely that smartphones have “destroyed” the millennial generation, in the provocative formulation of Jean Twenge’s 2017 Atlantic essay, than that very young children are being ruined by growing up with iPads. What’s more likely to ruin young kids are parents who lack the cultural confidence to raise them well regardless of what devices are set into their hands. A society that lacks a clear sense of a human future is not going to raise children well, period. The profound lack of anxiety around technology among the young is precious, reality-based, and needs to be channeled wisely. Today’s young kids, in this respect, are better off than today’s adolescents and young adults. But they need to learn the poetic art of humanism to guide them away from the utopian dreams that will diminish their humanity.

Being human means being stuck with imperfections, sometimes painful ones, having to do with judgment, suffering, recognition, and debt. Debt, and not just monetary debt, is a more fundamental and foundational part of being human than we sometimes dare imagine. It will never be expunged. Any technological effort to escape or deprecate our identity as creatures who have been imbued with life by forces not our own will not emancipate us from our debt to those forces, be they natural or supernatural. Instead of self-actualizing or consummating our humanity, that sort of effort will in fact destroy it. Our givenness is not only inescapable; it is at the core of the good news about who we are. Those who would reject Mars in favor of going technologically subhuman or posthuman to escape the constitutive human indebtedness they fear will only propagate bad reasons for using technology to escape truly human progress — the progress that begins with that first step and grand leap of human love onto the surface of Mars.

One reason antihumanism is so popular is that so much of human life is just a mess. Technological progress, focused by a love of Mars, will help us to clean it up. When the path toward a love of Mars is opened to our pro-human imagination and memory, we can restore good order to human life in a way that’s transformative but not exactly revolutionary. In the new “age of man” — the meaning of the old Germanic term that gives us the English “world” — the even older Western words for “world” will regain their significance: The Latin mundus means clean and elegant, while the Greek cosmos denotes an orderly arrangement.

The first target in the cleanup operation is our relationship with time. A now-familiar new form of anxiety and alienation attends the breakneck rise of digital life, which accelerates and disincarnates our experience of everyday life. While the digital revolution threatens to place earthbound life onto a trajectory of disembodied speed that outstrips human capabilities — and, ultimately, human participation — Mars strikes a long-persistent contrast. There, the potentiality of life is waiting. The idea of the fullness of time — of waiting until the time is right — and the responsibility that comes with acting in the fullness of time, come to the fore in our millennia-old, mythically intimate experience with Mars. The Red Planet reminds us of the bountiful and life-affirming natural and human resources that are lost when technologies of speed outstrip our measure.

Online, it is already almost impossible to feel at home in human time. Mars, a planet free from that problem — and the distance will always make instant communication with Earth impossible — embodies the promise that the cosmos is not destined to rush away from us faster than we can hang on. Because of its location outside of digital time, and its readiness to be received into human time, Mars offers a generative site where technological development can once again be made to serve the science of natural and human life.

That service, however, cannot take place without a disciplined effort on Earth to recover human time. We face the perverse temptation to race against the clock of digital time before all is lost. But the poetic practice of humanistic love demands not only human agency but human patience. The most talented and diligent of us must do the work of organizing and reorganizing human effort and human excellence accordingly.

The rediscovery of the grand frontier will smooth the way to that sort of tremendous pivot not by speeding up time, as we might imagine, but by slowing it down. It’s of the essence of grandeur — in contrast to greatness — to slow our human tempo in a way that makes circumstances more forgiving of a gracefully methodical approach. Such an approach reveals that the reality of the natural world, with its living beings and its inanimate objects, cannot simply be skirted, hacked, plowed under, or slapped around. It must be fully attended to, and, in that sense, honored. That is a matter of orienting our whole person, body, mind, and soul, to the reality of the natural world. It is also a matter of recovering and preserving the lived experience of natural and human time, and the fullness of both kinds of time. In so doing, the discipline of attention that practice entails can orient our whole person toward taking our place in poetic, cosmic, and ultimately divine time.

These thoughts should make intuitive sense for people who spend their lives where the rubber meets the road, in crisis situations where time is of the essence. You can see it especially in the global martial arts tradition. It is so powerful and simple that it has even influenced Hollywood, whether in cartoonish allegorical form — as in the Matrix trilogy — or in gritty realist guise — “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast,” Mark Wahlberg intones in Shooter, repeating a classic Marine maxim that’s sometimes simply reduced to the Zen-like koan “Slow is fast.” Martial arts are a remarkable reminder of how the physicality of disciplined attention to being human can have transformative effects on what appears to be our “uncontrollable” environment.

In a sense, where greatness presumes to impose the will on the environment, so often leading to swift and catastrophically prideful falls, grandeur illustrates how we and our environment are porous, constitutive of a larger cosmic whole wherein time is not what the modern scientific imagination, and the speed of the digital revolution, have made it seem: tyrannically regimented, inexorably linear, and fundamentally hostile. Approaching Mars in an act of humanistic love requires we firmly return to humbly attending to the natural world — a move that itself demands our patient, disciplined recovery of the experience of natural human time.

The next step in our cosmic, human cleanup involves reworking our earthly endeavors in imitation of the conceptual and practical model conveyed by our love for Mars. In his most famous speech promoting the Apollo program, President Kennedy came close to articulating a similar mission:

We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

In his day, Mars was out of reach. But the limits of the Moon as a catalyst for a humanism of love were clear. Neither in poetic experience nor in mythic authority will the Moon ever be a New Earth in waiting. Instead, the Moon was ultimately a technical and political challenge. Surely, our first human landing on another heavenly body marked a turning point in cosmic time and the poetic development of our human spirit. Yet the destiny by which the Moon landing was intelligible and purposive points not to increasing our technical excellence but to coming more fully into our human love by embracing Mars — environmentally the first and only potential New Earth, to the exclusion of any other known planet, moon, or asteroid. Embracing Mars can lead us to “organize and measure the best of our energies and skills” in accordance with human love. Embracing only the Moon will not.

Yet the memory latent in Kennedy’s mission — standing with Mars in a cosmic, intimate, and given relationship of loving destiny — does point toward a newfound application of natural and human science to our earthly home. Because love is a humanist aesthetic applicable to all fields of human endeavor, we can jettison old models that sought to press progress forward by substituting some form of greatness for love. As aerospace engineer Rand Simberg argued in these pages (“Getting Over ‘Apolloism’,” Spring/Summer 2016), nostalgia for the plan of the Apollo missions — to use space as a catalyst for “national unity” — is dangerously misplaced. Not only was that unity an illusion at the time, he implies, but today it is much harder to foster. Even so, he supports reopening “the high frontier” of space, maintaining public support by pursuing space technologies that are harmonious and connected with technologies useful on Earth. He lists energy, transportation, and environmental technologies as examples.

Once we come of cultural age into a mature, considered love for Mars, and see what happens when we act on that love, our crises and challenges on Earth can be recast, as can our menu of choices in meeting them. Rather than panic and rancor, scripted according to the prevailing social and political battle lines that have replaced the grand frontier, we will be more apt to find confidence, courage, and creativity. And rather than applying these virtues to the virtual world that draws us deeper into antihuman utopias, we’ll apply them to the metal-and-plastic, flesh-and-blood, brick-and-mortal world that forms an essential bridge between analog and digital life. It shouldn’t be a surprise that this approach will also happen to fit in logically with the reality that our younger kids now experience.

The fact is, the best technology for acting on our love of Mars is also important Earth technology, and the best Earth technology is excellent practice for perfecting the tools we’ll need to get past today’s crisis, establish a specific livable future, and carry it into the cosmos. The chief example here is climate change: Planetary climate control should be a natural step for pleasant human living as well as an intelligent way to preserve the best of the environment — not a panicked and guilty response to our own perceived sins. Other good examples, following Simberg, are transportation, which has lagged absurdly since the invention of the jet engine, and technologies of memory, including artificial intelligence, which need to be put to better service than automated curation and organizing data in the cloud.

But we also ought now to see the development of the Internet and social media and its inwardness as ultimately useful tools, despite our growing anxieties about them. Humanistic love also applies to endeavors where we’ve been too blind to see the right path forward, and our explosive growth directed at undue inwardness can be redirected and reorganized in light of our needs as we voyage into the high frontier. On Earth, our social media habits tend unnaturally toward dehumanizing cycles of self-absorption and active boredom. But at the grand frontier, amid the long distances and disorienting isolation of the Mars journey and the many early years of building life on Mars, the newly destiny-oriented context of our connectivity can turn these toward positive cycles of exchange.

Even as natural science takes its pride of organizational place above the other sciences, loving Mars will have an effect on the many other realms of human endeavor and specialization. The fields of construction, instruction, organization, transaction, and protection all stand to be re-conceptualized, refashioned, and renewed. Both on Mars and on Earth, the new Space Age we ought to plunge into should come along with a new Earth Age. The two are part of a larger cosmic whole. Eventually, in an echo of Dante’s divine and cosmic comedy, poetry, and the humanities in train, will be restored to their proper relationship of love with the sciences.

At a moment when digital machinery on Earth threatens to subjugate humans and nature to the mastery of automated things, Mars calls out to us in poetic voice from the heavens to return technology to the service of a truly natural science — a natural science returned to the service of living human creatures.

October 21, 2016

November 4, 2014